Derrida in the University, Or the Liberal Arts in Deconstruction / C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Unlimited Responsibility of Spilling Ink Marko Zlomislic

ISSN 1393-614X Minerva - An Internet Journal of Philosophy 11 (2007): 128-152 ____________________________________________________ The Unlimited Responsibility of Spilling Ink Marko Zlomislic Abstract In order to show that both Derrida’s epistemology and his ethics can be understood in terms of his logic of writing and giving, I consider his conversation with Searle in Limited Inc. I bring out how a deconstruction that is implied by the dissemination of writing and giving makes a difference that accounts for the creative and responsible decisions that undecidability makes possible. Limited Inc has four parts and I will interpret it in terms of the four main concepts of Derrida. I will relate signature, event, context to Derrida’s notion of dissemination and show how he differs from Austin and Searle concerning the notion of the signature of the one who writes and gives. Next, I will show how in his reply to Derrida, entitled, “Reiterating the Differences”, Searle overlooks Derrida’s thought about the communication of intended meaning that has to do with Derrida’s distinction between force and meaning and his notion of differance. Here I will show that Searle cannot even follow his own criteria for doing philosophy. Then by looking at Limited Inc, I show how Derrida differs from Searle because repeatability is alterability. Derrida has an ethical intent all along to show that it is the ethos of alterity that is called forth by responsibility and accounted for by dissemination and difference. Of course, comments on comments, criticisms of criticisms, are subject to the law of diminishing fleas, but I think there are here some misconceptions still to be cleared up, some of which seem to still be prevalent in generally sensible quarters. -

Deconstruction for Critical Theory Handbook

Deconstruction Johan van der Walt Introduction Deconstruction is a mode of philosophical thinking that is principally associated with the work of the French philosopher Jacques Derrida. Considered from the perspective of the history of philosophical thinking, the crucial move that Derrida’s way of thinking makes is to shift the focus of inquiry away from a direct engagement with the cognitive content of ideas put forward in a text in order to focus, instead, on the way in which the text produces a privileged framework of meaning while excluding others. Instead of engaging in a debate with other philosophers – contemporary or past – about the ideas they articulated in their texts, Derrida commenced to launch inquiries into the way their texts relied on dominant modes of writing (and reading) to produce a certain semantic content and intent while excluding other modes of reading and, consequently, other possible meanings of the text. By focusing on the textuality of texts – instead of on their semantic content – Derrida’s thinking endeavoured to pay attention, not only to that which the text does not say, but also that which it cannot say. The explanation that follows will show that the “method” of deconstruction does not just consist in finding that other meanings of the text are possible or plausible, but, more importantly, in demonstrating that the possibility or plausibility of other meanings – supressed by the organisation of the text – alerts one to the infinite potentiality of meaning that necessarily exceeds the margins of the text and remains unsayable. In other words, by pointing out the instability of the dominant meaning organised by the text, deconstruction alerts one to the unsayable as such, that is, to that which no text can say but on which all texts remain dependent for being able to say what they manage to say. -

Depopulation: on the Logic of Heidegger's Volk

Research research in phenomenology 47 (2017) 297–330 in Phenomenology brill.com/rp Depopulation: On the Logic of Heidegger’s Volk Nicolai Krejberg Knudsen Aarhus University [email protected] Abstract This article provides a detailed analysis of the function of the notion of Volk in Martin Heidegger’s philosophy. At first glance, this term is an appeal to the revolutionary mass- es of the National Socialist revolution in a way that demarcates a distinction between the rootedness of the German People (capital “P”) and the rootlessness of the modern rabble (or people). But this distinction is not a sufficient explanation of Heidegger’s position, because Heidegger simultaneously seems to hold that even the Germans are characterized by a lack of identity. What is required is a further appropriation of the proper. My suggestion is that this logic of the Volk is not only useful for understanding Heidegger’s thought during the war, but also an indication of what happened after he lost faith in the National Socialist movement and thus had to make the lack of the People the basis of his thought. Keywords Heidegger – Nazism – Schwarze Hefte – Black Notebooks – Volk – people Introduction In § 74 of Sein und Zeit, Heidegger introduces the notorious term “the People” [das Volk]. For Heidegger, this term functions as the intersection between phi- losophy and politics and, consequently, it preoccupies him throughout the turbulent years from the National Socialist revolution in 1933 to the end of WWII in 1945. The shift from individual Dasein to the Dasein of the German People has often been noted as the very point at which Heidegger’s fundamen- tal ontology intersects with his disastrous political views. -

PHILOSOPHY 474 (Winter Term): PHENOMENOLOGY (Tues; Thurs, 1:00-2:30Pm)

MCGILL UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY (2017-2018) PHILOSOPHY 474 (Winter Term): PHENOMENOLOGY (Tues; Thurs, 1:00-2:30pm) Instructor: Professor Buckley Office: Leacock 929 Office Hours: Wednesday 3:30pm-5:30pm or by appointment (preferably sign-up by email: [email protected]) Teaching Assistant: Mr. Renxiang Liu (email: [email protected] ); Office: Leacock 923 Office Hours: Monday: 12:30-1:30 COURSE DESCRIPTION: This course serves as an introduction to the phenomenological movement. It focuses upon the motives behind Husserl's original development of "phenomenological reduction" and investigates the manner in which the thought of subsequent philosophers constitutes both an extension and a break with Husserl's original endeavour. TOPIC FOR 2017-2018: The course will consist of a careful reading of Martin Heidegger's seminal work Being and Time (trans. J. Macquarrie and J. Robinson (New York: Harper-Collins, 1962); Sein und Zeit (Tübingen: Max Niemeyer, 1979). The text is available at the Word Bookstore (cash or cheque only). SOME QUESTIONS TO BE CONSIDERED: 1) Background: How can Being and Time be read in view of Husserl's "transcendental" phenomenology? In what way are Husserl's and Heidegger's concerns similar? What other philosophical currents form the horizon within which this text was written (e.g. Neo-Kantianism, positivism, psychologism)? How does Heidegger see his work within the context of the entire history of Western philosophy? 2) The project: What does Heidegger mean by the "recollection of the question -

Kant, Neo-Kantianism, and Phenomenology Sebastian Luft Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Philosophy Faculty Research and Publications Philosophy, Department of 7-1-2018 Kant, Neo-Kantianism, and Phenomenology Sebastian Luft Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. Oxford Handbook of the History of Phenomenology (07/18). DOI. © 2018 Oxford University Press. Used with permission. Kant, Neo-Kantianism, and Phenomenology Kant, Neo-Kantianism, and Phenomenology Sebastian Luft The Oxford Handbook of the History of Phenomenology Edited by Dan Zahavi Print Publication Date: Jun 2018 Subject: Philosophy, Philosophy of Mind, History of Western Philosophy (Post-Classical) Online Publication Date: Jul 2018 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198755340.013.5 Abstract and Keywords This chapter offers a reassessment of the relationship between Kant, the Kantian tradi tion, and phenomenology, here focusing mainly on Husserl and Heidegger. Part of this re assessment concerns those philosophers who, during the lives of Husserl and Heidegger, sought to defend an updated version of Kant’s philosophy, the neo-Kantians. The chapter shows where the phenomenologists were able to benefit from some of the insights on the part of Kant and the neo-Kantians, but also clearly points to the differences. The aim of this chapter is to offer a fair evaluation of the relation of the main phenomenologists to Kant and to what was at the time the most powerful philosophical movement in Europe. Keywords: Immanuel Kant, neo-Kantianism, Edmund Husserl, Martin Heidegger, Marburg School of neo-Kantian ism 3.1 Introduction THE relation between phenomenology, Kant, and Kantian philosophizing broadly con strued (historically and systematically), has been a mainstay in phenomenological re search.1 This mutual testing of both philosophies is hardly surprising given phenomenology’s promise to provide a wholly novel type of philosophy. -

Marburg Neo-Kantianism As Philosophy of Culture

SamanthaMatherne (Santa Cruz) Marburg Neo-Kantianism as Philosophy of Culture 1Introduction Although Ernst Cassirer is correctlyregarded as one of the foremost figures in the Neo-Kantian movement thatdominated Germanyfrom 1870 – 1920,specifying ex- actlywhat his Neo-Kantianism amountstocan be achallenge. Not onlymustwe clarify what his commitments are as amember of the so-called MarburgSchool of Neo-Kantianism, but also giventhe shift between his earlyphilosophyof mathematics and naturalscience to his later philosophyofculture, we must con- sider to what extent he remained aMarburgNeo-Kantian throughout his career. With regard to the first task, it is typical to approach the MarburgSchool, which was foundedbyHermann Cohen and Paul Natorp, by wayofacontrast with the otherdominant school of Neo-Kantianism, the Southwest or Baden School, founded by Wilhelm Windelband and carried forward by Heinrich Rick- ert and Emil Lask. The going assumption is that these two schools were ‘rivals’ in the sense that the MarburgSchool focused exclusively on developing aKantian approach to mathematical natural sciences(Naturwissenschaften), while the Southwest School privileged issues relatingtonormativity and value, hence their primary focus on the humanities (Geisteswissenschaften). If one accepts this ‘scientist’ interpretation of the MarburgSchool, one is tempted to read Cas- sirer’searlywork on mathematicsand natural science as orthodoxMarburgNeo- Kantianism and to then regardhis laterwork on the philosophyofculture as a break from his predecessors, veeringcloser -

Hermann Cohen - Kant Among the Prophets1

The Journal ofJewish Thought and Philosphy, Vol. 2, pp. 185-199 © 1993 Reprints available directly from the publisher Photocopying permitted by licence only Hermann Cohen - Kant among the Prophets1 Gillian Rose University of Warwick, UK The selective reception by general philosophy and social scientific methodology in the European tradition of the mode of neo- Kantianism founded by Hermann Cohen (1842-1918) has con- tributed to the widespread undermining of conceptual thinking in favour of the hermeneutics of reading. To assess Cohen's thought as a reading and re-originating of the Jewish tradition involves a predicament of circularity: for the question of reading and origin is not neutral but derives from the partial reception of the object addressed. The task of reassessment changes from a methodologi- cally independent survey to a challenge posed by current thought, unsure of its modernity or post-modernity, to re-establish contact with a formative but long-forgotten part of itself. No longer solely academic, this exercise will have to confront two especially difficult aspects of Cohen's thought. First, he did not "read" Kant, he destroyed the Kantian philosophy. In its place, he founded a "neo- Kantianism" on the basis of a logic of origin, dif- ference and repetition. As a logic of validity, this neo-Kantian math- esis is often at stake when its practitioners prefer to acknowledge 1 This paper was originally prepared for the Symposium, "The Playground of Textuality: Modern Jewish Intellectuals and the Horizon of Interpretation," First Annual Wayne State University Press Jewish Symposium, held in Detroit, 20-22 March, 1988. -

Jacques Derrida Law As Absolute Hospitality

JACQUES DERRIDA LAW AS ABSOLUTE HOSPITALITY JACQUES DE VILLE NOMIKOI CRITICAL LEGAL THINKERS Jacques Derrida Jacques Derrida: Law as Absolute Hospitality presents a comprehensive account and understanding of Derrida’s approach to law and justice. Through a detailed reading of Derrida’s texts, Jacques de Ville contends that it is only by way of Derrida’s deconstruction of the metaphysics of presence, and specifi cally in relation to the texts of Husserl, Levinas, Freud and Heidegger, that the reasoning behind his elusive works on law and justice can be grasped. Through detailed readings of texts such as ‘To Speculate – on Freud’, Adieu, ‘Declarations of Independence’, ‘Before the Law’, ‘Cogito and the History of Madness’, Given Time, ‘Force of Law’ and Specters of Marx, de Ville contends that there is a continuity in Derrida’s thinking, and rejects the idea of an ‘ethical turn’. Derrida is shown to be neither a postmodernist nor a political liberal, but a radical revolutionary. De Ville also controversially contends that justice in Derrida’s thinking must be radically distinguished from Levinas’s refl ections on ‘the Other’. It is the notion of absolute hospitality – which Derrida derives from Levinas, but radically transforms – that provides the basis of this argument. Justice must, on de Ville’s reading, be understood in terms of a demand of absolute hospitality which is imposed on both the individual and the collective subject. A much needed account of Derrida’s infl uential approach to law, Jacques Derrida: Law as Absolute Hospitality will be an invaluable resource for those with an interest in legal theory, and for those with an interest in the ethics and politics of deconstruction. -

Twentieth-Century French Philosophy Twentieth-Century French Philosophy

Twentieth-Century French Philosophy Twentieth-Century French Philosophy Key Themes and Thinkers Alan D. Schrift ß 2006 by Alan D. Schrift blackwell publishing 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of Alan D. Schrift to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 2006 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd 1 2006 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Schrift, Alan D., 1955– Twentieth-Century French philosophy: key themes and thinkers / Alan D. Schrift. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-4051-3217-6 (hardcover: alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-4051-3217-5 (hardcover: alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-1-4051-3218-3 (pbk.: alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-4051-3218-3 (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Philosophy, French–20th century. I. Title. B2421.S365 2005 194–dc22 2005004141 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Set in 11/13pt Ehrhardt by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed and bound in India by Gopsons Papers Ltd The publisher’s policy is to use permanent paper from mills that operate a sustainable forestry policy, and which has been manufactured from pulp processed using acid-free and elementary chlorine-free practices. -

The Role of Ontology in the Just War Tradition

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Texas A&M University “THAT TRUTH THAT LIVES UNCHANGEABLY”: THE ROLE OF ONTOLOGY IN THE JUST WAR TRADITION A Dissertation by PHILLIP WESLEY GRAY Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2006 Major Subject: Political Science © 2006 PHILLIP WESLEY GRAY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED “THAT TRUTH THAT LIVES UNCHANGEABLY”: THE ROLE OF ONTOLOGY IN THE JUST WAR TRADITION A Dissertation by PHILLIP WESLEY GRAY Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Cary J. Nederman Committee Members, Elisabeth Ellis Nehemia Geva J. R. G. Wollock Head of Department, Patricia Hurley December 2006 Major Subject: Political Science iii ABSTRACT “That Truth that Lives Unchangeably”: The Role of Ontology in the Just War Tradition. (December 2006) Phillip Wesley Gray, B.A., University of Dayton Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Cary J. Nederman The just war tradition as we know it has its origins with Christian theology. In this dissertation, I examine the theological, in particular ontological, presuppositions of St. Augustine of Hippo in his elucidation of just war. By doing so, I show how certain metaphysical ideas of St. Augustine (especially those on existence, love, and the sovereignty of God) shaped the just war tradition. Following this, I examine the slow evacuation of his metaphysics from the just war tradition. -

Learning to Live Finally Learning to Live Finally the Last Interview

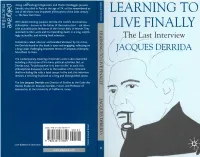

ZJ ~T~} 'Along with Ludwig Wittgenstein and Martin Heidegger, Jacques Q, Qj Derrida, who died in Paris at the age of 74, will be remembered as —— one of the three most important philosophers of the 20th century.' LEARNING TO >*J — The New York Times r— ^-» With death looming, Jacques Derrida, the world's most famous __ *T\ philosopher - known as the father of 'deconstruction' - sat down ~' with journalist Jean Birnbaum of the French daily Le Monde. They LIVE FINALLY revisited his life's work and his impending death in a long, surpris• ingly accessible, and moving final interview. The Last Interview Sometimes called 'obscure' and branded 'abstruse' by his critics, the Derrida found in this book is open and engaging, reflecting on a long career challenging important tenets of European philosophy 'ACOUES DERRIDA from Plato to Marx. The contemporary meaning of Derrida's work is also examined, including a discussion of his many political activities. But, as Derrida says, 'To philosophize is to learn to die'; as such, this philosophical discussion turns to the realities of his imminent death-including life with a fatal cancer. In the end, this interview remains a touching final look at a long and distinguished career. The late Jacques Derrida was Director of Studies at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, France, and Professor of Humanities at the University of California, Irvine. ISBN 978-0-230-53785-9 9 780230 537859 Cover illustration © Carol Hayes Learning to Live Finally Learning to Live Finally The Last Interview Jacques Derrida An Interview with Jean Birnbaum Translated by Pascale-Anne Brault and Michael Naas With a bibliography by Peter Krapp All rights reserved. -

Kantianism and Anti-Kantianism in Russian Revolutionary Thought1

CON-TEXTOS KANTIANOS. International Journal of Philosophy N.o 8, Diciembre 2018, pp. 218-241 ISSN: 2386-7655 Doi: 10.5281/zenodo.2331766 Kantianism and Anti-Kantianism in Russian Revolutionary Thought1 VADIM CHALY• Immanuel Kant Baltic Federal University, Russia Abstract This paper restates and subjects to analysis the polemics in Russian pre-revolutionary Populist and Marxist thought that concerned Kant’s practical philosophy. In these polemics Kantian ideas influence and reinforce the Populist personalism and idealism, as well as Marxist revisionist reformism and moral universalism. Plekhanov, Lenin, and other Russian “orthodox Marxists” heavily criticize both trends. In addition, they generally view Kantianism as a “spiritual weapon” of the reactionary bourgeois thought. This results in a starkly anti-Kantian position of Soviet Marxism. In view of this the 1947 decision to preserve Kant’s tomb in Soviet Kaliningrad becomes something of an experimentum crucius that challenges the soundness of the theory. Key words Soviet Marxism, Populism, Kant, ideal, person. Resumen Este artículo reevalúa y analiza las polémicas en el pensamiento marxista y populista de la Rusia pre-revolucionaria acerca de la filosofía práctica de Kant. En estas polémicas, las ideas kantianas influyeron y reforzaron el personalismo e idealismo populistas, así como el reformismo revisionista marxista y el universalismo moral. Plekhanov, Lenin y otros “ortodoxos marxistas” rusos criticaron con dureza ambas tendencias. Además, generalmente consideraron el Kantismo como un “arma espiritual” del pensamieo burgués reaccionario. Esto resultó en una fuerte posición anti-kantiana en el marxismo soviético. Teniendo esto a la vista, la decisión de 1947 de preservar la tumba de Kant 1 Written as part of research project, supported by Russian Foundation for Basic Research (#16-03-50202) and “Project 5-100”.