University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Independent Personal1ty of the Palestinians*

THE INDEPENDENT PERSONAL1TY OF THE PALESTINIANS* Türkkaya ATAÖV The exodus and the dispersal of the Palestinian people af- ter the occupation of their land by the racist Zionist entity could not hinder the tradition of national expression. This expression, linked to the national question, was even developed as a reaction to foreign invasion. No doubt, the Palestinian armed struggle, follovving the Israeli attack in 1967, has caused an explosion of a potential energy not only in terms of military force, but in the realm of culture and arts. Palestinian culture, in the form of poetry, folk tales, popular singing, dancing, national costumes, embroidery, ceramics, carving, glass and metal work or various other forms of expression, is the vivid proof of the existence of a homeland and a people's yearning for it. The Palestinian masses, under occupation or in exile, are gathering, safeguarding and developing their ovvn culture, knowing ful 1 well that the preservation of culture is an effective vvay of resistance to attempts undermining national consciousness. The Zionist entity has not only looted the land of the Palestini- ans, but is also suppressing their culture and what is more,trying to usurpe it from them. But the Palestinians are engaged in a struggle to obtain recognition of their independent personality and existence. In spite of Zionist aggression, the ı oots of a peop- le, deep in the Palestinian soil, cannot be erased. * The Palestinians were avvare of the dangers posed by Zio- nist immigration, much earlier than generally accepted. Throug- hout many centuries, the Holy Land prospered under the tolerant rule of Arab and Ottoman Turkish sovereigns, who safeguarded * This paper was prepared for an international conference in Baghdad (Iraq) in 1979. -

P.L.O. Lnlonaatlon Bulletin CONTENTS to OUR READERS

P.L.O. lnlonaatlon bulletin CONTENTS TO OUR READERS Solidarity is an important weJpon for helping the peoples of the world overcome: oppres sion and injustice. The support <~nd solidJrity which the Palesti nian people receive helps us to continue our just struggle for our just cause. We <~re grateful for the_ solidJrity Jnd support we get, ' but although we hJve many friend~ around the world, our enemies Me still strong Jnd fmmiddble. They arc better Jrmed, better equipped, and much wealthier thJn we. Nevertheless, though we may Editorial ....................................3 possess limited nJeJns, our dcter Palestine Notes .............................. .4 min<ltion Jnd willingness to PLO Communique On Arab Summit ...............7 sacrifice is unlimited. The world forces of liberation, of which we Israeli Terror Cannot Break Our People's Resistance ... 9 are proud to be a part, are the Occupation Diary ............................ 1 2 emerging forces, and it is to us Israeli Government Re-expels Oawasmeh And Milhem 14 that the future belongs. The Israeli Military Occupation In Galilee ............. 16 forces of oppression have had Z ionism In Practice ...........................22 their dJy, Jnd shall be consigned to the dusthin of history . Document: "There Is No Palestinian People" By Meir Kahane ...........................25 We thank all of our friends Establishing The Zionist Stranglehold throughout the world for the By Faris Glubb ............................28 letters of support and encoura gement you have sent to us. World Events ................................31 Surely, we and other liberation 29th November: movements will continue on the International Palestine Solidarity Day .......... 33 road to victory. Solidarity ..................................35 Letters to "Palestine" .........................35 PRICE ... ............ .. .......... L.L. -

British Major-General Charles George Gordon and His Legacies, 1885-1960 Stephanie Laffer

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2010 Gordon's Ghosts: British Major-General Charles George Gordon and His Legacies, 1885-1960 Stephanie Laffer Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES GORDON‘S GHOSTS: BRITISH MAJOR-GENERAL CHARLES GEORGE GORDON AND HIS LEGACIES, 1885-1960 By STEPHANIE LAFFER A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2010 Copyright © 2010 Stephanie Laffer All Rights Reserve The members of the committee approve the dissertation of Stephanie Laffer defended on February 5, 2010. __________________________________ Charles Upchurch Professor Directing Dissertation __________________________________ Barry Faulk University Representative __________________________________ Max Paul Friedman Committee Member __________________________________ Peter Garretson Committee Member __________________________________ Jonathan Grant Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii For my parents, who always encouraged me… iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation has been a multi-year project, with research in multiple states and countries. It would not have been possible without the generous assistance of the libraries and archives I visited, in both the United States and the United Kingdom. However, without the support of the history department and Florida State University, I would not have been able to complete the project. My advisor, Charles Upchurch encouraged me to broaden my understanding of the British Empire, which led to my decision to study Charles Gordon. Dr. Upchurch‘s constant urging for me to push my writing and theoretical understanding of imperialism further, led to a much stronger dissertation than I could have ever produced on my own. -

THE PREVALENCE of GUILE: Deception Through Time and Across Cultures and Disciplines

2 February 2007 THE PREVALENCE OF GUILE: Deception through Time and across Cultures and Disciplines by Barton Whaley “The Game is so large that one sees but a little at a time.” —Kipling, Kim (1901), Chapter 10 Foreign Denial & Deception Committee National Intelligence Council Office of the Director of National Intelligence Washington, DC 2007 -ii- CONTENTS Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................... iv INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 1. In a Nutshell: What I Expected & What I Found 2. Force versus Guile 3. The Importance of Guile in War, Politics, and Philosophy PART ONE: OF TIME, CULTURES, & DISCIPLINES ................................................. 11 4. Tribal Warfare 5. The Classical West 6. Decline in the Medieval West 7. The Byzantine Style 8. The Scythian Style 9. The Renaissance of Deception 10. Discontinuity: “Progress” and Romanticism in the 19th Century 11. The Chinese Way 12. The Japanese Style 13. India plus Pakistan 14. Arabian to Islamic Culture 15. Twentieth Century Limited 16. Soviet Doctrine 17. American Roller-coaster and the Missing Generation 18. Twenty-First Century Unlimited: Asymmetric Warfare Revisited PART TWO: LIMITATIONS ON THE PRACTICE OF DECEPTION ............................ 58 19. Biological Limitations: Nature & Nurture 20. Cultural Limitations: Philosophies, Religions, & Languages 21. Social Limitations: Ethical Codes and Political -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Camp David's Shadow

Camp David’s Shadow: The United States, Israel, and the Palestinian Question, 1977-1993 Seth Anziska Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 © 2015 Seth Anziska All rights reserved ABSTRACT Camp David’s Shadow: The United States, Israel, and the Palestinian Question, 1977-1993 Seth Anziska This dissertation examines the emergence of the 1978 Camp David Accords and the consequences for Israel, the Palestinians, and the wider Middle East. Utilizing archival sources and oral history interviews from across Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, the United States, and the United Kingdom, Camp David’s Shadow recasts the early history of the peace process. It explains how a comprehensive settlement to the Arab-Israeli conflict with provisions for a resolution of the Palestinian question gave way to the facilitation of bilateral peace between Egypt and Israel. As recently declassified sources reveal, the completion of the Camp David Accords—via intensive American efforts— actually enabled Israeli expansion across the Green Line, undermining the possibility of Palestinian sovereignty in the occupied territories. By examining how both the concept and diplomatic practice of autonomy were utilized to address the Palestinian question, and the implications of the subsequent Israeli and U.S. military intervention in Lebanon, the dissertation explains how and why the Camp David process and its aftermath adversely shaped the prospects of a negotiated settlement between Israelis and Palestinians in the 1990s. In linking the developments of the late 1970s and 1980s with the Madrid Conference and Oslo Accords in the decade that followed, the dissertation charts the role played by American, Middle Eastern, international, and domestic actors in curtailing the possibility of Palestinian self-determination. -

Oman's Foreign Policy : Foundations and Practice

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 11-7-2005 Oman's foreign policy : foundations and practice Majid Al-Khalili Florida International University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Al-Khalili, Majid, "Oman's foreign policy : foundations and practice" (2005). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1045. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/1045 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida OMAN'S FOREIGN POLICY: FOUNDATIONS AND PRACTICE A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS by Majid Al-Khalili 2005 To: Interim Dean Mark Szuchman College of Arts and Sciences This dissertation, written by Majid Al-Khalili, and entitled Oman's Foreign Policy: Foundations and Practice, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. Dr. Nicholas Onuf Dr. Charles MacDonald Dr. Richard Olson Dr. 1Mohiaddin Mesbahi, Major Professor Date of Defense: November 7, 2005 The dissertation of Majid Al-Khalili is approved. Interim Dean Mark Szuchman C lege of Arts and Scenps Dean ouglas Wartzok University Graduate School Florida International University, 2005 ii @ Copyright 2005 by Majid Al-Khalili All rights reserved. -

The Revival of the Ibadi Imamate in Oman and the Threat to Muscat, 1913-20 J

The Revival of the Ibadi Imamate in Oman and the Threat to Muscat, 1913-20 J. E. Peterson By the beginning of 1913 Oman was reaching the nadir of its fortunes, marking the middle of a century of frustration and decline. Although the Sultan, Faisal b. Turki Al Bñ Sa`idi, was the nominal ruler of all the country, he only exercised full control over the capital area of Muscat and Matrah, and the coastal strip to the northwest known as al-Batinah. Otherwise, the interior of Oman went its own nearly-independent way, hindered only by the presence of a few walls (representatives of the Sultan) in the principal towns, such as Nizwa or Sama'il. The period of rebellion from 1913 to 192o is important in the history of Oman for a number of reasons. The restoration of the Ibadi Imamate, periodically revived since the beginning of the nineteenth century, was an accomplishment of this period that lasted for forty-two years. But the method of its establishment pre- sented a grave threat to the government of the Sultanate, weakened by fifty years of decline, and continually attacked by the religious zealots of the interior for its close relationship with the British. The revolt of 1923-2o was essentially tribal in nature, with the institution of the Imamate superimposed on it in order to lend legitimacy and unity to the uprising. There were two factors which made it a deadly menace to Muscat and gave it as good a chance of wresting control of the entire country away from the Sultan as had the move- ment of 1868-71.' The first was the revival of the Imamate, without which little tribal cooperation could have been expected and the revolt could have only repeated the attack of 1895 at most.' The second factor was the development of this uprising into a unified stand of co-operation between both the Ghafiri and Hinawi factions, something that even the 1868-71 movement had not been able to achieve.' Thus the combination of forces set in motion in the spring of 1913 posed the most dangerous threat to the regime in Muscat since Muscat had become the capital of the country. -

THE FORMULATION of BRITAIN's POLICY TOWARDS EGYPT: 1922-1925 Eugene ROTHMAN a Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philo

THE FORMULATION OF BRITAIN'S POLICY TOWARDS EGYPT: 1922-1925 Eugene ROTHMAN A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Faculty of Arts, University of London. London, September 1979 ProQuest Number: 10672715 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672715 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT The years immediately following the First World War were extremely important for the formulation of Britain's policy towards Egypt, a British Protectorate since 1914. In this connection, the years 1922 to 1925, the last years of Lord Allenby's tenure as Britain's High Commissioner in Egypt, were critical. Allenby, who was appointed in 1919 in order to suppress nationalist- inspired rioting in Egypt, adopted a surprising policy of moderation. He soon forced the British government to unilaterally declare Egypt's independence in 1922. This apparent success was followed by the adoption of a modern consti tution in Egypt and the British withdrawal from the entanglements of Egypt's administration. Still Allenby's career ended in seeming frustration in 1925: negotiations between Britain and Egypt failed in 1924, to be followed by the assassination of the British Governor General of the Sudan, Sir Lee z' Stack, and Allenby's harsh ultimatum to the Egyptian government in November 1924 effectively reinstituting British control of Egypt's administration. -

Visitors to College

E X E T E R C O L L E G E Register 2011 Contents Editorial 4 From the Rector 4 From the President of the MCR 7 From the President of the JCR 9 Elizabeth Helen Gili (1913–2011) 11 Leslie Philip Le Quesne CBE (1919–2011) 12 Sidney Martin Starkie (1922–2010) 13 Robert Henry Robinson (1927–2011) 15 William Aaron DeJanes (1978–2011) 18 Armin Kroesbacher (1990–2011) 19 Sandra Fredman, FBA, by Jonathan Herring 20 The Chapel, by Helen Orchard and Lister Tonge 21 The College Staff, by William Jensen 24 Ruskin College and Exeter, by Tony Moreton 26 B.W. Henderson, by Keith Bradley 28 William Lockhart, by Nicholas Schofield 31 A Spitfire Pilot Celebrates his Failures, by Richard Gilman 33 Uncovering the Secrets of the Old Masters, by Rachel Billinge 36 What Now for Higher Education?, by Reeta Chakrabarti 38 The Patient Doctor, by B.L.D. Phillips 40 Pre-prandial, by John Symons 42 Poems of Oxford, by Virginie Basset 44 Population Ageing in Vietnam, by Matthew Tye 45 Failed States and Extralegal Groups, by Christine Cheng 47 Solving Climate Change with Wind and Solar Power, by Matthias Fripp 49 College Notes and Queries 51 The Governing Body 56 Honours and Appointments 58 Publications Reported 59 Class Lists in Honour Schools and Honour Moderations 2011 61 Distinctions in Moderations and Prelims 2011 63 Graduate Degrees 2010–11 63 Major Scholarships, Studentships, Bursaries 2011–12 66 College Prizes 2010–11 68 University Prizes 2010–11 68 Graduate Freshers 2011 69 Undergraduate Freshers 2011 71 Visiting Students 2011–12 73 Deaths 74 Marriages 76 Births 77 Notices 79 1 Editor Christopher Kirwan was Official Fellow and Lecturer in Philosophy from 1960 to 2000. -

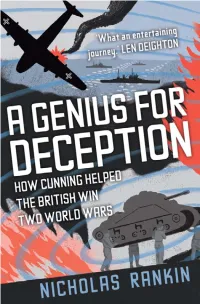

A Genius for Deception.Pdf

A Genius for Deception This page intentionally left blank A GENIUS FOR DECEPTION How Cunning Helped the British Win Two World Wars nicholas rankin 1 1 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2008 by Nicholas Rankin First published in Great Britain as Churchill’s Wizards: The British Genius for Deception, 1914–1945 in 2008 by Faber and Faber, Ltd. First published in the United States in 2009 by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rankin, Nicholas, 1950– A genius for deception : how cunning helped the British win two world wars / Nicholas Rankin. p. cm. — (Churchill’s wizards) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-538704-9 1. Deception (Military science)—History—20th century. 2. World War, 1914–1918—Deception—Great Britain. 3. World War, 1939–1945—Deception—Great Britain. 4. Strategy—History—20th century. -

Military Intelligence Blunders

Military Intelligence Blunders Colonel John Hughes-Wilson Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc. NEW YORK Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc. 19 West 21st Street New York NY 10010-6805 First published in the UK by Robinson Publishing Ltd 1999 Copyright © John Hughes-Wilson 1999 Maps and diagrams copyright © John Hughes-Wilson 1999 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publishers. ISBN 0-7394-0689-2 Manufactured in the USA For Victor Andersen + of the British Intelligence Services And Val Heller + of the US Defense Intelligence Agency Who both made it possible Contents Preface ix 1 On Intelligence 1 2 The Misinterpreters - D-Day, 1944 16 3 "Comrade Stalin Knows Best" - Barbarossa, 1941 38 4 "The Finest Intelligence in Our History" - Pearl Harbor, 1941 60 5 "The Greatest Disaster Ever to Befall British Arms" - Singapore, 1942 102 6 Uncombined Operations - Dieppe, 1942 133 7 "I Thought We Were Supposed to be Winning?" - The Tet Offensive, 1968 165 8 "Prime Minister, the War's Begun" - Yom Kippur, 1973 218 9 "Nothing We Don't Already Know" - The Falkland Islands, 1982 260 10 "If Kuwait Grew Carrots, We Wouldn't Give a Damn" - The Gulf, 1991 308 11 Will It Ever Get Any Better? 353 Suggested Reading List 361 Glossary of Terms 365 Index 367 vn Maps and Diagrams The Intelligence Cycle 6 An Intelligence Collection Plan's Essential Elements of Information 11 Dispositions June 1944 22 The Allied Deception Plans for D-Day 30 Operation Barbarossa 45 Pearl Harbor - Japan's Grab for Empire, 1941/2 75 Malaya and Singapore, 1942 112 Disaster at Dieppe, 19 August 1942 153 The Vietnam War, 1956-75 182 The Tet Offensive, South Vietnam, 30-31 January 1968 199 "Greater Israel", 1967-73 232 Yom Kippur, 1973: Suez and Sinai 255 The Falklands War, 1982: relative distances 276 The South Atlantic, 1982 293 A Threat Curve 306 The Gulf War, 1990/1 324 via Preface This is a book that tries to tell the story of some recent events, all within living memory, from a different angle: intelligence.