Originating Outside the Island, Westerners As Well As Non-Westerners, on the Other

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Same Planet, a Different World

The following is a firsthand account of a medical-relief mission to western Indonesia that Dennis Whitehead, MD ’75, undertook in March 2005 in response to severe earthquakes that devastated the region only months after the tsunami struck. As this issue of Buffalo Physician was going to press, Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast. We contacted Whitehead and asked him if he had been involved in relief efforts following the storm. We learned he had just Same Planet, a Different World returned from six days of working with the Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals to support search-and- rescue efforts in downtown New Orleans, assist boat crews in the flooded areas, treat rescue workers, complete MEDICAL RELIEF IN INDONESIA, POST-TSUNAMI AND EARTHQUAKE EMS site surveys and examine shelter patients in rural St. Tammany Parish, northeast of New Orleans. By DENNIS C. WHITEHEAD, MD ’75 At our request, Whitehead agreed to report on his Gulf Coast experience in the next issue of Buffalo Physician. —S. A. UNGER, EDITOR All that remains of Banda Aceh’s densely populated residential area. The hills in the background shielded most of the downtown business district. Nias Island Same Planet, a Different World India Indian Ocean Cambodia My thirtieth medical class reunion took place this past April, and I was looking forward to it very much. I have greatly enjoyed seeing my Sumatra classmates every five years and catching up on their lives. My former room- Malaysia mate, Jack Freer, MD ’75, now a clinical professor of medicine at UB, was 8.7 earthquake coordinator for our class this year and I promised him I would be there for the festivities. -

Economics Development Analysis Journal (2) (2021)

Economics Development Analysis Journal (2) (2021) Economics Development Analysis Journal http://journal.unnes.ac.id/sju/index.php/edaj Analysis of Factors Affecting Poverty in the North Sumatra Province Arif Rahman1 , 2M. Syafii, 3Sukma Hayati Hakim Faculty of Economics and Business University of North Sumatra Article Abstract Information ___________________________________________________________________ North Sumatra is the province with the largest number of poor people in 2019 with the fifth highest ________________ poverty percentage on the island of Sumatra. This province has a good potential for accelerating History of Article economic growth and improving the quality of life if all levels of society are empowered with all their Received January 2021 capabilities in carrying out productive business activities, and can access to socio-economic Accepted March 2021 resources. This study aimed to determine and analyze the effect of the real GDP per capita variable, Pusblished May 2021 the open unemployment rate, and the average length of schooling simultaneously and partially on ________________ the poverty rate in 33 cities and regencies of North Sumatra Province in 2017-2019. It used secondary Keywords: data using the Eviews program, while analysis technique used was panel data regression. Based on Poverty, GDP, the research results, it was found that the real GDP per capita, the open unemployment rate, and the Unemployment, average length of schooling simultaneously had a significant effect on the poverty level. Per capita Education real GRDP and average length of schooling partially had a negative and significant effect on poverty __________________ rate. Meanwhile, the open unemployment rate had no significant effect on poverty. The variable that has the most dominant influence on the level of poverty was real GDP per capita. -

Lowalangi: from the Name of an Ethnic Religious Figure to the Name of God

HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-8050, (Print) 0259-9422 Page 1 of 6 Original Research Lowalangi: From the name of an ethnic religious figure to the name of God Author: This article shows the success of local cultural adaptation strategies in communicating the 1 Sonny E. Zaluchu gospel to people of the Nias ethnicity in North Sumatra, Indonesia. This adaptation is the Affiliation: name Lowalangi, the name of the god of the pre-Christian era, to become the name of God, 1Department of Theology, the creator and saviour of the world incarnated in the person of Jesus Christ. As a result, the Indonesia Baptist Theological use of this name was not limited to a translation process. Still, the whole concept of divinity for Seminary, Semarang, the Nias people was transferred and transformed into a Christian understanding. They know Indonesia him as Lowalangi, have faith in him and pray to him in that name. The author uses a Corresponding author: comparative analysis with other places in Indonesia. The author tries to establish parallelism Sonny Zaluchu, with methods used elsewhere, assuming that the methods used tend to be the same. [email protected] Contribution: Churches and Christians in Nias are strengthened in their beliefs by praying Dates: and mentioning Lowalangi’s name, which imparts the same faith quality as the biblical use of Received: 14 Nov. 2020 Accepted: 27 Feb. 2021 God’s personal name. This adaptation can be a strategy for introducing the gospel in Published: 20 Apr. 2021 missiology and church planting in response to local culture as a wealth that cannot be negated. -

Hans Harmakaputra, Interfaith Relations in Contemporary Indonesia

Key Issues in Religion and World Affairs Interfaith Relations in Contemporary Indonesia: Challenges and Progress Hans Abdiel Harmakaputra PhD Student in Comparative Theology, Boston College I. Introduction In February 2014 Christian Solidarity Worldwide (CSW) published a report concerning the rise of religious intolerance across Indonesia. Entitled Indonesia: Pluralism in Peril,1 this study portrays the problems plaguing interfaith relations in Indonesia, where many religious minorities suffer from persecution and injustice. The report lists five main factors contributing to the rise of religious intolerance: (1) the spread of extremist ideology through media channels, such as the internet, religious pamphlets, DVDs, and other means, funded from inside and outside the country; (2) the attitude of local, provincial, and national authorities; (3) the implementation of discriminatory laws and regulations; (4) weakness of law enforcement on the part of police and the judiciary in cases where religious minorities are victimized; and (5) the unwillingness of a “silent majority” to speak out against intolerance.2 This list of factors shows that the government bears considerable responsibility. Nevertheless, the hope for a better way to manage Indonesia’s diversity was one reason why Joko Widodo was elected president of the Republic of Indonesia in October 2014. Joko Widodo (popularly known as “Jokowi”) is a popular leader with a relatively positive governing record. He was the mayor of Surakarta (Solo) from 2005 to 2012, and then the governor of Jakarta from 2012 to 2014. People had great expectations for Jokowi’s administration, and there have been positive improvements during his term. However, Human Rights Watch (HRW) World Report 2016 presents negative data regarding his record on human rights in the year 2015, including those pertaining to interfaith relations.3 The document 1 The pdf version of the report can be downloaded freely from Christian Solidarity Worldwide, “Indonesia: Pluralism in Peril,” February 14, 2014. -

Natalis English

International Journal of Progressive Sciences and Technologies (IJP SAT) ISSN: 2509-0119. © 2018International Journals of Sciences and High Technologies http://ijpsat.ijsht-journals.org Vol . 9 No. 2 July 2018, pp. 170-176 Analysis of Post -Local Government Proliferation Practice on Socioeconomic Change in Nias Regency Natalis Deswati Br. Laowo Department of Regional and Rural Development Planning, University of Sumatera Utara North Sumatra, Indonesia Prof. Dr. Suwardi Lubis, MS Department of Communication Science , Faculty of Political and Social Science University of Sumatra Utara, North Sumatra, Indonesia Prof. Dr. H. B. Tarmizi, SU Department of Economic Development, Faculty of Economics and Business University of Sumatra Utara, North Sumatra, Indonesia Abstract - This study aims to determine the Human Development Index (HDI) before and after the local government proliferation practice in Nias Regency. Type of the research is descriptive with quanti tative approach. The research used secondary data of 8 years before the proliferation practice (2002 -2009) and 8 years after the profileration practice (2010 -2017), the data were analyzed by paired sample t -test at α = 0.05 . The results showed that there was a difference between the positive Human Development Index (HDI) before and after the proliferation practice in Ni as Regency. Keywords - Human Development Index ; Proliferation Practice; Nias Regency. I. INTRODUCTION allocating development and governance The immense territory of Indonesia mechanisms. Unequal distribution of with its vast geographic range of islands, natural resources in Indonesia is also one diverse socio-cultural co nditions and large of the causes of the need for a system of populations, all this affects the process of government that facilitates the management of natural resources which is Corresponding Author: Natalis Deswati Br. -

CHAPTER V CLOSING 5.1 Conclusion Ethnic Minority Entrepreneurship Has Become a Phenomenon That Is Widely Found in All Parts of T

CHAPTER V CLOSING 5.1 Conclusion Ethnic minority entrepreneurship has become a phenomenon that is widely found in all parts of the world. This type of entrepreneurship is driven by migration out of the place of origin to get better opportunities in other areas. The movement that occurs causes people from one ethnic group to join with other ethnic groups in the destination. This assimilation causes ethnic migrants to be outnumbered by local ethnic groups in the destination that have been there for a long time. This has led to the term ethnic minority. Efforts to earn income through doing business by ethnic minority then formed the term ethnic minority entrepreneurship. Nias is an ethnic who has a long history with West Sumatra area, especially the city of Padang. Although still outnumbered by Minangkabau ethnicity, Nias people in Padang City already have strong roots because of the nature of Nias people who have a strong sense of kinship. From an economic standpoint, over time, progressive changes have been found in the economic order of the Nias community in the city of Padang. In the past Nias people only worked as farmers, becoming fishermen or laborers in the city of Padang. Now, Nias people in Padang who are a minority have found livelihoods in various fields, including entrepreneurship. Those who originally came with limited language differences, mediocre education and did not have the capital managed to make a 132 decent living and raise the dignity of their ancestors who had set foot first in the city of Padang with low standard of life. -

North Nias Regency

LAFAU BEACH MAP NORTH NIAS REGENCY NORTH NIAS REGENCY NIAS ISLAND NIAS ISLAND WEST NUSA TENGGARA PROVINCE Pasir Berbunyi Beach Tureloto Beach Lotu Lafau Beach Gunung Sitoli C. TURELOTO BEACH Binaka Airport Coordinate : 1°25’49,65‘’ N & 97°8‘29,95’‘E Tourism Business Opportunities (including the investment code for every business ield): Gido a. Star hotel (5511) Lahomi b. Food and Beverages Service : Restaurant (56101), Café (56303) & Bar (56301) c. Spa (96122) and Villa (55194) Lolomatua Mountain d. Sport Facilities: Tennis Field (93116) and Golf Course (93112) e. Recreational Park (93232) and Theme Park (93210) f. Organization of Meeting, Incentive, Conference and Exhibition (82301) g. Enclave Management (91022) of the “Living Road history” ethnic village Hinako Archipelago INVITATION TO INVEST IN TOURISM BASED COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT AT : Teluk Dalam ADDRESS Deputy for Tourism Destination and Tourism Industry Development Sapta Pesona Building, 4th Floor Contact Us : INDONESIA Jl. Merdeka Barat No. 17 [email protected] Jakarta Pusat 10110 [email protected] Indonesia T : +62 21 3838040, 3838029 www.kemenpar.go.id F : +62 21 34833865 www.indonesia-tourism-investment.com PRESENTING NORTH NIAS REGENCY, NIAS ISLAND, NORTH SUMATRA PROVINCE. MARKETING 2. TOURISM DEVELOPMENT In order to optimize the tourism development in Nias 1. DEVELOPMENT OVERVIEW Island, the local government implemented several marketing strategy as follows: a. Quality and quantity improvement of the Nias A. PASIR BERBUNYI BEACH Island tourism marketing program through a Coordinate : 1°29’22,71‘’ N & 97°20‘54,73’‘E wide variety of media promotion and extend its Tourism Business Opportunities (including the reach. -

Tiga Tipe Tata Ruang Desa Tradisional Di Nias Selatan, Sumatera Utara

KALPATARU, Majalah Arkeologi Vol. 28 No.2, November 2019 (45-60) TIGA TIPE TATA RUANG DESA TRADISIONAL DI NIAS SELATAN, SUMATERA UTARA Three Types of Spatial Patterns in South Nias Traditional Villages, North Sumatera Elyada Wigati Pramaresti Museum Ullen Sentalu, Jalan Boyong KM. 25, Kaliurang Barat, Hargobinangun, Kabupaten Sleman, Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta [email protected] Naskah diterima : 31 Juli 2019 Naskah diperiksa : 10 Agustus 2019 Naskah disetujui : 29 Oktober 2019 Abstract. South Nias is one of many regions in Indonesia that still mantains the existence of traditional settlement. Villages in this regency have unique characteristic shown from their linear forms with two rows of houses facing each other. Although the villages all seem similar, but in fact, there are three different spatial patterns. This research would be related with the disparity of these traditional settlement patterns. Qualitative method was used in this research by obtaining data through field observations, interviews, and literature study. The result reveals that the traditional settlement patterns were in the shapes of branched linear, I-shaped linear, and T-shaped linear. This classification was based on the variation of shapes and location of the village material components. Another purpose in this research is to do a documentation about South Nias traditional villages including their original components which become scarce nowadays due to being damaged by natural factors or deliberately replaced by modern components. Keywords: South Nias, Traditional Village, Spatial Pattern Abstrak. Nias Selatan adalah salah satu wilayah di Indonesia yang masih mempertahankan keberadaan permukiman tradisional. Desa-desa yang ditemukan di kabupaten tersebut memiliki karakteristik yang unik, yaitu berbentuk linear dengan dua baris rumah yang saling berhadapan. -

Contestation of Ethnic Identity in Forming Ethno- Territorial in Pakpak Bharat Regency, North Sumatra

International Journal of Sociology and Anthropology Research Vol.2, No.2, pp.1-15, October 2016 ___Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) CONTESTATION OF ETHNIC IDENTITY IN FORMING ETHNO- TERRITORIAL IN PAKPAK BHARAT REGENCY, NORTH SUMATRA Erond L. Damanik1 1Ph.D Student, Faculty of Social Science and Political Science. Airlangga University, Surabaya-Indonesia. 1Lecturer at Departement of Anthrophology, Faculty of Sociel Science, State University of Medan (UNIMED)-Medan-Indonesia ABSTRACT: Contestation of ethnic identity in a pluralistic society in Dairi is a phenomenon of ethnicity in order to achieve a political goal of ethno-territorial formation in Pakpak Bharat. Domination of immigrant gives a great impact on socio-cultural attributes, exclusion of ethno-religious and political deprivation for Pakpak ethnic in Dairi since the colonial era. The situation has caused an evasive identity as well as the breakdown of inter-ethnic relations. Momentum of government institution after the fall of the New Order opened wide opportunities to build ethno- territorial. Ethno-territorial formation in Pakpak Bharat is started with the contestation on the socio-cultural formulation of core identity, and seeps into the room of socio-religious, politics and government. Contestation of these three ethnic identities affects each other and cannot be separated from national policy. Contestation of ethnic identity on the formation of ethno-territorial is very essential phenomenon to understand political reality. Ethnicity becomes is the best strategy to mobilize ethnic to achieve political objective, that is the establishment of Pakpak Bharat. It happens because ethnicity consists of ethnic identity as a personal reference, a source of motivation, behavior and social construction in order to interpret and read the society in Dairi. -

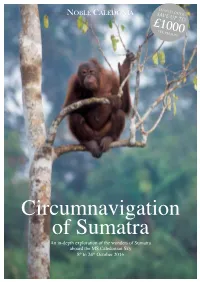

Circumnavigation of Sumatra an In-Depth Exploration of the Wonders of Sumatra Aboard the MS Caledonian Sky 8Th to 24Th October 2016 Clown Fish Lake Toba

LAUNCH OFFER - SAVE UP TO £1000 PER PERSON Circumnavigation of Sumatra An in-depthaboard exploration the MSth ofOctober Caledonian the wonders 2016 Sky of Sumatra 8th to 24 Clown Fish Lake Toba oin us for a rare event, a circumnavigation of the world’s Our View sixth largest island. Opportunities to visit Sumatra, a land of After our successful voyages MALAYSIA J Gunung Leuser history and mystery are scarce and are usually limited to one around Sumatra in 2013, we Banda Aceh National Park region of the island. Our visit in the autumn of 2016 will be all are delighted to be returning Belawan once again with an in-depth Medan encompassing and include opportunities to see orangutans in Simeulue Islands Malacca exploration of the island. Lake Toba Nias Island their natural habitat, to snorkel over coral reefs, to visit remote Separated from mainland Asia Singapore Bukittinggi by the Strait of Malacca and from islands where native indigenous people still live in isolation, SUMATRA free to practice their timeless tribal lore and to explore where Java by the Strait of Sunda, Sumatra Siberut Island Padang lies at the heart of geological and few have been before. Our voyage will be one of contrasts, Bengkulu Belitung cultural crossroads. Spectacular Islands from lush rainforests to diverse cultures, spectacular wildlife volcanoes and mysterious calderas Krakatau and an intriguing history, all of which will be made all the more are many along the Barisan Island captivating by our onboard expedition team who are experts in Mountains, the long spinal range of Marco Polo and is often the island following Sumatra’s west referred to as the Isle of Gold: the natural world. -

BAB IV RUANG KETIGA PERJUMPAAN NIAS PADANG KRISTEN DAN MINANGKABAU MUSLIM 4.1. Pendahuluan Salah Satu Bukti Yang Dapat Menunjukk

76 BAB IV RUANG KETIGA PERJUMPAAN NIAS PADANG KRISTEN DAN MINANGKABAU MUSLIM 4.1. Pendahuluan Salah satu bukti yang dapat menunjukkan kuatnya pengaruh Islam di kota Padang adalah ketiadaan tersedianya pilihan mata pelajaran agama lain selain Islam di sekolah negeri. Akibatnya ketika jadwal mata pelajaran agama berlangsung maka tidak jarang siswa dan siswi non-muslim diberi izin ke perpustakaan untuk menggunakan jam pelajaran tersebut atau bahkan diperbolehkan pulang duluan jikalau jadwalnya terletak di akhir jam pelajaran. Hal ini menuntut siswa dan siswi non-muslim harus memiliki cara lain untuk mendapatkan haknya yaitu memperoleh ilmu dari mata pelajaran agama yang merupakan mata pelajaran wajib. Situasi ini juga dialami oleh anak-anak Nias Padang Kristen yang memilih bersekolah di sekolah negeri. Masalah ini pun ditanggapi oleh pihak gereja yang merupakan lembaga keagamaan dan bekerjasama dengan departemen agama kota Padang. Gereja BNKP yang ada di Padang memberikan solusi kepada anggota jemaat yang menjadi siswa dan siswi sekolah negeri dengan menyediakan tenaga pengajar untuk mata pelajaran agama Kristen. Selain itu, departemen agama juga mengeluarkan blanko penilaian yang sah kepada pihak gereja untuk dapat memenuhi kebutuhan siswa dan siswi dalam penilaian raport di sekolah negeri. Sikap ini 77 merupakan satu dari sekian banyak hal yang terjadi di dalam ruang ketiga orang Nias Padang Kristen. Tindakan ini menjadi strategi yang mampu membantu mereka untuk dapat bertahan sebagai masyarakat diaspora dan minoritas. Bhabha mengatakan dalam teorinya bahwa hal yang dilakukan oleh pihak terjajah di dalam ruang ketiga merupakan sesuatu yang “beyond” dimana ia tidak meninggalkan masa lalu namun juga tidak sepenuhnya menyerahkan diri kepada hal yang baru. -

A STUDY of the NIAS REVIVAL in INDONESIA Julia Theis Dermawan 1. Introduction in the Years Betwe

[AJPS 6:2 (2003), pp. 247-263] A STUDY OF THE NIAS REVIVAL IN INDONESIA Julia Theis Dermawan 1. Introduction In the years between 1915 and 1940, the Niasan church in Indonesia rapidly grew. During this twenty-five year period, between the Golden Jubilee and the Diamond Jubilee, the number of baptized believers in Nias increased from about 20,000 to 135,000. The great revival movement that occurred in the island caused this phenomenal growth. Known as the Fangesa Dodo (“the Great Repentance”),1 it manifested a great conviction for and confession of sin. This paper is a historical report on the Nias revival from available sources and will show how it contributed to the overall growth of the church. This paper has also a pragmatic purpose: to remind all Asian Christians of the importance of the outpouring of the Holy Spirit for the growth of Christianity in Asia today. 2. The Location of the Revival 2.1 Geography Nias is the largest of a chain of Indonesian islands in the Indian Ocean off the west coast of Sumatra. It has an area of 1,569 square miles (or 4,064 sq. km) and is subject to earthquakes. The chief town is Gunung Sitoli on the northeast coast.2 1 Lee Ira Bruckner, “The History and Character of the Niasan People Movement in Indonesia, 1865-1940” (D.Miss. dissertation, Fuller Theological Seminary, 1979), p. 86. 2 “Nias,” The Encyclopedia Americana International Edition (Danbury, Conn.: Grolier, c1997), vol. 20, p. 300. 248 Asian Journal of Pentecostal Studies 6:2 (2003) 2.2 People Most of the 400,000 people are descendants of Proto-Malays who built megalithic tombs all over the island.