Culture in Balance : Texts Crossing Borders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary Composer Vladimir Jovanović and His Role in the Renewal of Church Byzantine Music in Serbia from the 1990S Until Today

Interdisciplinary Studies in Musicology 19, 2019 @PTPN Poznań 2019, DOI 10.14746/ism.2019.19.1 GORDANA BLAGOJEVIĆ https://orcid.org/0000–0001–7883–8071 Institute of Ethnography SASA, Belgrade Contemporary composer Vladimir Jovanović and his role in the renewal of church Byzantine music in Serbia from the 1990s until today ABSTRACT: This work focuses on the role of the composer Vladimir (Vlada) Jovanović in the rene- wal of church Byzantine music in Serbia from the 1990s until today. This multi-talented artist wor- ked and created art in his native Belgrade, with creativity that exceeded local frames. This research emphasizes Jovanović’s pedagogical and compositional work in the field of Byzantine music, which mostly took place through his activity in the St. John of Damascus choir in Belgrade. The author analyzes the problems in implementation of modal church Byzantine music, since the first students did not hear it in their surroundings, as well as the responses of the listeners. Special attention is paid to students’ narratives, which help us perceive the broad cultural and social impact of Jovanović’s creative work. KEYWORDS: composer Vladimir (Vlada) Jovanović, church Byzantine music, modal music, St. John of Damascus choir. Introduction This work was written in commemoration of a contemporary Serbian composer1 Vladimir Jovanović (1956–2016) with special reference to his role in the renewal of church Byzantine music in Serbia from the beginning of the 1990s until today.2 In the text we refer to Vladimir Jovanović as Vlada – a shortened form of his name, which relatives, friends, colleagues and students used most of- ten in communication with the composer, as an expression of sincere closeness. -

A Strange Loop

A Strange Loop / Who we are Our vision We believe in theater as the most human and immediate medium to tell the stories of our time, and affirm the primacy and centrality of the playwright to the form. Our writers We support each playwright’s full creative development and nurture their unique voice, resulting in a heterogeneous mix of as many styles as there are artists. Our productions We share the stories of today by the writers of tomorrow. These intrepid, diverse artists develop plays and musicals that are relevant, intelligent, and boundary-pushing. Our plays reflect the world around us through stories that can only be told on stage. Our audience Much like our work, the 60,000 people who join us each year are curious and adventurous. Playwrights is committed to engaging and developing audiences to sustain the future of American theater. That’s why we offer affordably priced tickets to every performance to young people and others, and provide engaging content — both onsite and online — to delight and inspire new play lovers in NYC, around the country, and throughout the world. Our process We meet the individual needs of each writer in order to develop their work further. Our New Works Lab produces readings and workshops to cultivate our artists’ new projects. Through our robust commissioning program and open script submission policy, we identify and cultivate the most exciting American talent and help bring their unique vision to life. Our downtown programs …reflect and deepen our mission in numerous ways, including the innovative curriculum at our Theater School, mutually beneficial collaborations with our Resident Companies, and welcoming myriad arts and education not-for-profits that operate their programs in our studios. -

Slovenia – Mine, Yours, Ours

07 ISSN 1854-0805 July 2011 Slovenia – mine, yours, ours • INTERVIEW: Milan Kučan, Lojze Peterle • PEOPLE: Dr. Mrs. Mateja De Leonni Stanonik, Md. • SPORTS: Rebirth of Slovenian tennis • ART & CULTURE: Festival Ljubljana • SLOVENIAN DELIGHTS: Brda cherries are the best contents 1 In focus 6 Slovenia celebrates its 20th anniversary editorial 2 Interview 10 Milan Kučan and Lojze Peterle 3 Before and after 16 20 years of Slovenian Press Agency (STA) 4 Art & culture 27 THE WORLD ON A STAGE Vesna Žarkovič, Editor 5 Green corner 32 Julon, the first in the world Slovenia – mine, yours, ours with “green” polyamide 1 2 Regardless the differences among us Slovenians, we nevertheless have a com- 6 Natural trails 48 mon view of what sort of a country we want to live in: a developed, open, tol- erant, free and solidaristic one – among creative individuals in one of the most Slovenian caves and their telliness developed countries, to put it shortly. We also set these values as our goal 20 years ago when Slovenia gained its independence. How do the former president of the MONTHLY COMMENTARY 4 presidency of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia Milan Kučan and the first prime “No” to referendum like jumping off a train? minister Lojze Peterle see those times today, 20 years later, how do they remem- ber them and how do they project them to the present time? Read about it in this BUSINESS 14 issue’s interview. The Economy is Being Revived and Exports are I was hopeful then and I’m hopeful now, says Dan Damon, Journalist, BBC World Increasing Service, in his letter: “I was hopeful for an independent Slovenia even before 1991 A LETTER 20 because I believed (unlike quite a few Slovenians I spoke to at the time) that Slo- venia would be viable as a small, self-governing nation. -

Kirkus Reviews on Our Website by Logging in As a Subscriber

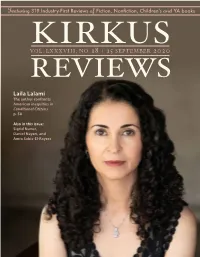

Featuring 319 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books VOL.KIRKUS LXXXVIII, NO. 18 | 15 SEPTEMBER 2020 REVIEWS Laila Lalami The author confronts American inequities in Conditional Citizens p. 58 Also in this issue: Sigrid Nunez, Daniel Nayeri, and Amra Sabic-El-Rayess from the editor’s desk: The Way I Read Now Chairman BY TOM BEER HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # Among the many changes in my daily life this year—working from home, Chief Executive Officer wearing a mask in public, watching too much TV—my changing read- MEG LABORDE KUEHN ing habits register deeply. For one thing, I read on a Kindle now, with the [email protected] Editor-in-Chief exception of the rare galley sent to me at home and the books I’ve made TOM BEER a point of purchasing from local independent bookstores or ordering on [email protected] Vice President of Marketing Bookshop.org. The Kindle was borrowed—OK, confiscated—from my SARAH KALINA boyfriend at the beginning of the pandemic, when I left dozens of advance [email protected] reader copies behind at the office and accepted the reality that digital gal- Managing/Nonfiction Editor ERIC LIEBETRAU leys would be a practical necessity for the foreseeable future. I can’t say that I [email protected] love reading on my “new” Kindle—I’m still a sucker for physical books after Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK all these years—but I’ll admit that it fulfills its purpose efficiently. And I do [email protected] Tom Beer rather enjoy the instant gratification of going on NetGalley or Edelweiss Young Readers’ Editor VICKY SMITH and dispatching multiple books to my device in one fell swoop—a harmless [email protected] form of bingeing that affords a little dopamine rush. -

The Bear in Eurasian Plant Names

Kolosova et al. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine (2017) 13:14 DOI 10.1186/s13002-016-0132-9 REVIEW Open Access The bear in Eurasian plant names: motivations and models Valeria Kolosova1*, Ingvar Svanberg2, Raivo Kalle3, Lisa Strecker4,Ayşe Mine Gençler Özkan5, Andrea Pieroni6, Kevin Cianfaglione7, Zsolt Molnár8, Nora Papp9, Łukasz Łuczaj10, Dessislava Dimitrova11, Daiva Šeškauskaitė12, Jonathan Roper13, Avni Hajdari14 and Renata Sõukand3 Abstract Ethnolinguistic studies are important for understanding an ethnic group’s ideas on the world, expressed in its language. Comparing corresponding aspects of such knowledge might help clarify problems of origin for certain concepts and words, e.g. whether they form common heritage, have an independent origin, are borrowings, or calques. The current study was conducted on the material in Slavonic, Baltic, Germanic, Romance, Finno-Ugrian, Turkic and Albanian languages. The bear was chosen as being a large, dangerous animal, important in traditional culture, whose name is widely reflected in folk plant names. The phytonyms for comparison were mostly obtained from dictionaries and other publications, and supplemented with data from databases, the co-authors’ field data, and archival sources (dialect and folklore materials). More than 1200 phytonym use records (combinations of a local name and a meaning) for 364 plant and fungal taxa were recorded to help find out the reasoning behind bear-nomination in various languages, as well as differences and similarities between the patterns among them. Among the most common taxa with bear-related phytonyms were Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (L.) Spreng., Heracleum sphondylium L., Acanthus mollis L., and Allium ursinum L., with Latin loan translation contributing a high proportion of the phytonyms. -

The Center for Slovenian Literature

Louis AdamiË S 2004 Presentation at book fairs: Leipzig, Prague (national Esad BabaËiË stand), Göteborg. Cooperation with LAF for the anthology “A Fine Andrej Blatnik Line: New Poetry from Eastern & Central Europe” and presenta- Berta Bojetu Lela B. Njatin tions in UK. Readings of four poets in Bosnia. Presentation of eight Primoæ »uËnik Boris A. Novak poets and writers in Czech republic. Aleπ Debeljak Maja Novak Milan Dekleva Iztok Osojnik 2005 Presentation of Slovenia, guest of honour at the book Mate Dolenc Boris Pahor fair in Prague, 5-8 May 2005. Evald Flisar Vera PejoviË Readings of younger poets in Serbia. Brane Gradiπnik Æarko Petan Niko Grafenauer Gregor Podlogar L 2006 First Gay poetry translation workshop in Dane. Herbert Grün Sonja Porle Presentation of Slovenian literature in Dublin. Andrej Hieng Jure Potokar “Six Slovenian Poets”, an anthology of six Slovenian poets, pub- Alojz Ihan Marijan Puπavec C lished by Arc Publications. Andrej Inkret Jana Putrle SrdiÊ Three evenings of Slovenian literature in Volkstheater, Vienna Drago JanËar Andrej Rozman Roza (thirteen authors). Jure Jakob Marjan Roæanc Alenka Jensterle-Doleæal Peter SemoliË 2007 Reading tour in Portugal. Milan Jesih Andrej E. Skubic Second Gay poetry translation workshop in Dane. Edvard Kocbek Gregor Strniπa Miklavæ Komelj Lucija Stupica Barbara Korun Tomaæ ©alamun Center for Slovenian Literature Ciril KosmaË Rudi ©eligo Metelkova 6 • SI-1000 Ljubljana • Slovenia The Trubar Foundation is a joint venture of Slovene Writers’ Edvard KovaË Milan ©elj Phone +386 40 20 66 31 • Fax +386 1 505 1674 Association (www.drustvo-dsp.si), Slovenian PEN and the Center Lojze KovaËiË Tone ©krjanec E-mail: [email protected] www.ljudmila.org/litcenter [for Slovenian Literature. -

Recent Publications in Music 2009

Fontes Artis Musicae, Vol. 56/4 (2009) RECENT PUBLICATIONS IN MUSIC R1 RECENT PUBLICATIONS IN MUSIC 2009 On behalf of the International Association of Music Libraries Archives and Documentation Centres / Pour le compte l'Association Internationale des Bibliothèques, Archives et Centres de Documentation Musicaux / Im Auftrag der Die Internationale Vereinigung der Musikbibliotheken, Musikarchive und Musikdokumentationszentren This list contains citations to literature about music in print and other media, emphasizing reference materials and works of research interest that appeared in 2008. Reporters who contribute regularly provide citations mainly or only from the year preceding the year this list is published in the IAML journal Fontes Artis Musicae. However, reporters may also submit retrospective lists cumulating publications from up to the previous five years. In the hope that geographic coverage of this list can be expanded, the compiler welcomes inquiries from bibliographers in countries not presently represented. Compiled and edited by Geraldine E. Ostrove Reporters: Austria: Thomas Leibnitz Canada: Marlene Wehrle China, Hong Kong, Taiwan: Katie Lai Croatia: Zdravko Blaţeković Czech Republic: Pavel Kordík Estonia: Katre Rissalu Finland: Ulla Ikaheimo, Tuomas Tyyri France: Cécile Reynaud Germany: Wolfgang Ritschel Ghana: Santie De Jongh Greece: Alexandros Charkiolakis Hungary: Szepesi Zsuzsanna Iceland: Bryndis Vilbergsdóttir Ireland: Roy Stanley Italy: Federica Biancheri Japan: Sekine Toshiko Namibia: Santie De Jongh The Netherlands: Joost van Gemert New Zealand: Marilyn Portman Russia: Lyudmila Dedyukina South Africa: Santie De Jongh Spain: José Ignacio Cano, Maria José González Ribot Sweden Turkey: Paul Alister Whitehead, Senem Acar United States: Karen Little, Liza Vick. With thanks for assistance with translations and transcriptions to Kersti Blumenthal, D. -

Matica Srpska Department of Social Sciences Synaxa Matica Srpska International Journal for Social Sciences, Arts and Culture

MATICA SRPSKA DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL SCIENCES SYNAXA MATICA SRPSKA INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR SOCIAL SCIENCES, ARTS AND CULTURE Established in 2017 2–3 (1–2/2018) Editor-in-Chief Časlav Ocić (2017‒ ) Editorial Board Dušan Rnjak Katarina Tomašević Editorial Secretary Jovana Trbojević Language Editor and Proof Reader Aleksandar Pavić Articles are available in full-text at the web site of Matica Srpska http://www.maticasrpska.org.rs/ Copyright © Matica Srpska, Novi Sad, 2018 SYNAXA СИН@КСА♦ΣΎΝΑΞΙΣ♦SYN@XIS Matica Srpska International Journal for Social Sciences, Arts and Culture 2–3 (1–2/2018) NOVI SAD 2018 Publication of this issue was supported by City Department for Culture of Novi Sad and Foundation “Novi Sad 2021” CONTENTS ARTICLES AND TREATISES Srđa Trifković FROM UTOPIA TO DYSTOPIA: THE CREATION OF YUGOSLAVIA IN 1918 1–18 Smiljana Đurović THE GREAT ECONOMIC CRISIS IN INTERWAR YUGOSLAVIA: STATE INTERVENTION 19–35 Svetlana V. Mirčov SERBIAN WRITTEN WORD IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR: STRUGGLING FOR NATIONAL AND STATEHOOD SURVIVAL 37–59 Slavenko Terzić COUNT SAVA VLADISLAVIĆ’S EURO-ASIAN HORIZONS 61–74 Bogoljub Šijaković WISDOM IN CONTEXT: PROVERBS AND PHILOSOPHY 75–85 Milomir Stepić FROM (NEO)CLASSICAL TO POSTMODERN GEOPOLITICAL POSTULATES 87–103 Nino Delić DEMOGRAPHIC TRENDS IN THE DISTRICT OF SMEDEREVO: 1846–1866 105–113 Miša Đurković IDEOLOGICAL AND POLITICAL CONFLICTS ABOUT POPULAR MUSIC IN SERBIA 115–124 Mirjana Veselinović-Hofman TOWARDS A BOTTOMLESS PIT: THE DRAMATURGY OF SILENCE IN THE STRING QUARTET PLAY STRINDBERG BY IVANA STEFANOVIĆ 125–134 Marija Maglov TIME TIIIME TIIIIIIME: CONSIDERING THE PROBLEM OF MUSICAL TIME ON THE EXAMPLE OF VLASTIMIR TRAJKOVIĆ’S POETICS AND THOMAS CLIFTON’S AESTHETICS 135–142 Milan R. -

Vlozek Oik 107 Za Splet.Pdf

ISSN 0351–5141 OTROK IN KNJIGA REVIJA ZA VPRAŠANJA MLADINSKE KNJIŽEVNOSTI, KNJIŽEVNE VZGOJE IN S KNJIGO POVEZANIH MEDIJEV The Journal of Issues Relating to Children’s Literature, Literary Education and the Media Connected with Books 107 2020 MARIBORSKA KNJIŽNICA OTROK IN KNJIGA izhaja od leta 1972. Prvotni zbornik (številke 1, 2, 3 in 4) se je leta 1977 preoblikoval v revijo z dvema številkama na leto; od leta 2003 izhajajo tri številke letno. The Journal is Published Three-times a Year in 700 Issues Uredniški odbor/Editorial Board: dr. Meta Grosman, mag. Darja Lavrenčič Vrabec, Maja Logar, Tatjana Pregl Kobe, dr. Gaja Kos, dr. Barbara Pregelj, dr. Peter Svetina in Darka Tancer-Kajnih; iz tujine: Gloria Bazzocchi (Univerza v Bologni), Juan Kruz Igerabide (Univerza Baskovske dežele), Dubravka Zima (Univerza v Zagrebu) Glavna in odgovorna urednica/Editor-in-Chief and Associate Editor: Darka Tancer-Kajnih Sekretar uredništva/Secretar: Robert Kereži Redakcija te številke je bila končana avgusta 2020 Za vsebino prispevkov odgovarjajo avtorji Prevodi sinopsisov: Marjeta Gostinčar Cerar Lektoriranje: Darka Tancer-Kajnih Izdaja/Published by: Mariborska knjižnica/Maribor Public Library Naslov uredništva/Address: Otrok in knjiga, Rotovški trg 6, 2000 Maribor, tel. (02) 23-52-100, telefax: (02) 23-52-127, elektronska pošta: [email protected] in [email protected] spletna stran: http://www.mb.sik.si Uradne ure: v četrtek in petek od 9.00 do 13.00 Revijo lahko naročite v Mariborski knjižnici, Rotovški trg 2, 2000 Maribor, elektronska pošta: [email protected]. Nakazila sprejemamo na TRR: 01270-6030372772 za revijo Otrok in knjiga Vključenost v podatkovne baze: MLA International Bibliography, NY, USA Ulrich’s Periodicals Directory, R. -

Titel Kino 4/2000 Nr. 1U.2

EXPORT-UNION OF GERMAN CINEMA 4/2000 Special Report: TRAINING THE NEXT GENERATION – Film Schools In Germany ”THE TANGO DANCER“: Portrait of Jeanine Meerapfel Selling German Films: CINE INTERNATIONAL & KINOWELT INTERNATIONAL Kino Scene from:“A BUNDLE OF JOY” GERMAN CINEMA Launched at MIFED 2000 a new label of Bavaria Film International Further info at www.bavaria-film-international.de www. german- cinema. de/ FILMS.INFORMATION ON GERMAN now with links to international festivals! GERMAN CINEMA Export-Union des Deutschen Films GmbH · Tuerkenstrasse 93 · D-80799 München phone +49-89-3900 9 5 · fax +49-89-3952 2 3 · email: [email protected] KINO 4/2000 6 Training The Next Generation 33 Soweit die Füße tragen Film Schools in Germany Hardy Martins 34 Vaya Con Dios 15 The Tango Dancer Zoltan Spirandelli Portrait of Jeanine Meerapfel 34 Vera Brühne Hark Bohm 16 Pursuing The Exceptional 35 Vill Passiert In The Everyday Wim Wenders Portrait of Hans-Christian Schmid 18 Then She Makes Her Pitch Cine International 36 German Classics 20 On Top Of The Kinowelt 36 Abwärts Kinowelt International OUT OF ORDER Carl Schenkel 21 The Teamworx Player 37 Die Artisten in der Zirkuskuppel: teamWorx Production Company ratlos THE ARTISTS UNDER THE BIG TOP: 24 KINO news PERPLEXED Alexander Kluge 38 Ehe im Schatten MARRIAGE IN THE SHADOW 28 In Production Kurt Maetzig 39 Harlis 28 B-52 Robert van Ackeren Hartmut Bitomsky 40 Karbid und Sauerampfer 28 Die Champions CARBIDE AND SORREL Christoph Hübner Frank Beyer 29 Julietta 41 Martha Christoph Stark Rainer Werner Fassbinder 30 Königskinder Anne Wild 30 Mein langsames Leben Angela Schanelec 31 Nancy und Frank Wolf Gremm 32 Null Uhr Zwölf Bernd-Michael Lade 32 Das Sams Ben Verbong CONTENTS 50 Kleine Kreise 42 New German Films CIRCLING Jakob Hilpert 42 Das Bankett 51 Liebe nach Mitternacht THE BANQUET MIDNIGHT LOVE Holger Jancke, Olaf Jacobs Harald Leipnitz 43 Doppelpack 52 Liebesluder DOUBLE PACK A BUNDLE OF JOY Matthias Lehmann Detlev W. -

ANDREJ ROZMAN ROZA Sample Little Rhyming Circus Poetry for Children Translation

ANDREJ ROZMAN ROZA Sample Little Rhyming Circus Poetry for children translation Sample translation Belarusian English German Hungarian Lithuanian Macedonian Russian Serbian ANDREJ ROZMAN ROZA Slovenian Book Agency, Metelkova 2b, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia Little Rhyming Circus T +386 1 369 58 20 F +386 1 369 58 30 E [email protected] W www.jakrs.si Poetry for children Andrej Rozman Roza Little Rhyming Circus Poetry for children Sample translation Original title: Mali rimski cirkus Uredila / Edited by Tanja Petrič Korekture / Proofreading Jason Blake, Kristina Sluga Založila in izdala Javna agencija za knjigo Republike Slovenije, Metelkova 2b, 1000 Ljubljana Zanjo Aleš Novak, direktor Issued and published by Slovenian Book Agency, Metelkova 2b, 1000 Ljubljana Aleš Novak, Director Fotografija na naslovnici / Cover photograph Jože Suhadolnik Grafično oblikovanje in prelom / Technical editing and layout Marko Prah Tisk / Print Grafex, d. o. o. Naklada / Print run 200 izvodov / 200 copies Darilna publikacija / Gift edition © Nosilci avtorskih pravic so avtorji / prevajalci sami, če ni navedeno drugače. © The authors/translators are the copyright holders of the text, unless stated otherwise. Ljubljana, 2017 CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 821.163.6-93(048.4) ROZMAN, Andrej, 1955- Little rhyming circus : poetry for children : sample translation / Andrej Rozman Roza. - Ljubljana : Javna agencija za knjigo Republike Slovenije = Slovenian Book Agency, 2017 Prevod dela: Mali rimski cirkus ISBN 978-961-94184-2-0 -

RECENT PUBLICATIONS in MUSIC 2013 Page 1 of 154

RECENT PUBLICATIONS IN MUSIC 2013 Page 1 of 154 RECENT PUBLICATIONS IN MUSIC 2013 Compiled and edited by Geraldine E. Ostrove and David Sommerfield This list contains citations to literature about music in print and other media, emphasizing reference materials and works of research interest that appeared primarily in 2012. Reporters who contribute regularly provide citations mainly or only from the year preceding the year this list is published in conjuction with Fontes artis musicae. However, reporters may also submit retrospective lists cumulating publications from up to the previous five years. In the hope that geographic coverage of this list can be expanded, the editor of Fontes welcomes inquiries from bibliographers in countries not presently represented. CONTRIBUTORS. Argentina: Estela Escalada Kenya: Santie De Jongh Austria: Thomas Leibnitz Macau SAR: Katie Lai Belgium: Johan Eeckeloo Malawi: Santie De Jongh Canada: Sean Luyk The Netherlands: Joost van Gemert China: Katie Lai New Zealand: Marilyn Portman Czech Republic: Pavel Kordik Nigeria: Santie De Jongh Denmark: Anne Ørbæk Jensen Russia: Lyudmila Dedyukina Estonia: Katre Rissalu Serbia: Radmila Milinković Finland: Tuomas Tyyri South Africa: Santie De Jongh France: Élisabeth Missaoui Spain: José Ignacio Cano, Maria José Germany: Susanne Heim González Ribot Greece: George Boumpous, Stephanie Sweden: Kerstin Carpvik, Lena Nettelbladt Merakos Taiwan: Katie Lai Hong Kong SAR: Katie Lai Turkey: Senem Acar, Paul Alister Whitehead Hungary: SZEPESI Zsuzsanna Uganda: Santie De Jongh Ireland: Roy Stanley United Kingdom: Rupert Ridgewell Italy: Federica Biancheri United States: Matt Ertz, Lindsay Hansen. Japan: SEKINE Toshiko With thanks for assistance with translations and transcriptions to Kersti Blumenthal, Maureen Buja, Ana Cristán, Paul Frank, Dr.