CEU Department of Medieval Studies in 2014/2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Štúdie O Dejinách

Štúdie o dejinách HISTORIA NOVA 6 Editor Peter Podolan Bratislava 2013 FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA UNIVERZITY KOMENSKÉHO V BRATISLAVE Katedra slovenských dejín Štúdie o dejinách HISTORIA NOVA 6 Editor Peter Podolan Bratislava 2013 Štúdie o dejinách HISTORIA NOVA 6 Editor Peter Podolan Bratislava 2013 HISTORIA NOVA 6 recenzenti prof. PhDr. Miroslav Daniš, CSc. doc. PhDr. Pavol Valachovič, CSc. zodpovedný redaktor Mgr. Peter Podolan, PhD. redakčná rada prof. PhDr. Jozef Baďurík, CSc. Mgr. Milota Floreková, PhD. prof. PhDr. Roman Holec, CSc. PhDr. Ľubomír Gašpierik, CSc. prof. Martin Homza, Dr. Mgr. Peter Podolan, PhD. prof. PhDr. Ján Lukačka, CSc. Mgr. Martin Vašš, PhD. PhDr. Peter Zelenák, CSc. © autori – Tomáš Adamčík, Eva Benková, Zofia Brzozowska, Mária Gaššová, Juraj Jankech, Lukáš Krajčír, Eduard Laincz, Ľudmila Maslíková, Pavol Matula, Adam Mesiarkin, Andrea Námerová, Peter Podolan, Jana Sofková, Vladimír Vlasko © Katedra slovenských dejín Filozofickej fakulty Univerzity Komenského © STIMUL – Poradenské a vydavateľské centrum Filozofickej fakulty UK adresa redakcie Katedra slovenských dejín Filozofická fakulta UK [email protected] Gondova ul. 2 P. O. Box 32 http://www.fphil.uniba.sk/index.php?id=historia_nova 814 99 Bratislava ISBN 978-80-8127-082-6 HISTORIA NOVA 6 HISTORIA NOVA 6 obsah ––––––––––––––––––––––– Ceci n'est pas une pipe (Peter PODOLAN) 8 štúdie Jana SOFKOVÁ Začiatky írskeho monasticizmu a kristianizačná činnosť írskych mníchov 11 Vladimír VLASKO Počiatky vlády Anjouovcov v Uhorsku 26 Ľudmila MASLÍKOVÁ Vývoj osídlenia a mestotvorný proces v najzápadnejšej časti Nitrianskej stolice do začiatku 15. storočia 48 Eva BENKOVÁ Dejiny vinohradníctva na panstve Červený Kameň v druhej polovici 18. storočia 71 Peter PODOLAN Sláwa Bohyně a původ gména Slawůw čili Slawjanůw.. -

Contemporary Composer Vladimir Jovanović and His Role in the Renewal of Church Byzantine Music in Serbia from the 1990S Until Today

Interdisciplinary Studies in Musicology 19, 2019 @PTPN Poznań 2019, DOI 10.14746/ism.2019.19.1 GORDANA BLAGOJEVIĆ https://orcid.org/0000–0001–7883–8071 Institute of Ethnography SASA, Belgrade Contemporary composer Vladimir Jovanović and his role in the renewal of church Byzantine music in Serbia from the 1990s until today ABSTRACT: This work focuses on the role of the composer Vladimir (Vlada) Jovanović in the rene- wal of church Byzantine music in Serbia from the 1990s until today. This multi-talented artist wor- ked and created art in his native Belgrade, with creativity that exceeded local frames. This research emphasizes Jovanović’s pedagogical and compositional work in the field of Byzantine music, which mostly took place through his activity in the St. John of Damascus choir in Belgrade. The author analyzes the problems in implementation of modal church Byzantine music, since the first students did not hear it in their surroundings, as well as the responses of the listeners. Special attention is paid to students’ narratives, which help us perceive the broad cultural and social impact of Jovanović’s creative work. KEYWORDS: composer Vladimir (Vlada) Jovanović, church Byzantine music, modal music, St. John of Damascus choir. Introduction This work was written in commemoration of a contemporary Serbian composer1 Vladimir Jovanović (1956–2016) with special reference to his role in the renewal of church Byzantine music in Serbia from the beginning of the 1990s until today.2 In the text we refer to Vladimir Jovanović as Vlada – a shortened form of his name, which relatives, friends, colleagues and students used most of- ten in communication with the composer, as an expression of sincere closeness. -

The Maiwa Guide to NATURAL DYES W H at T H Ey a R E a N D H Ow to U S E T H E M

the maiwa guide to NATURAL DYES WHAT THEY ARE AND HOW TO USE THEM WA L NUT NATURA L I ND IG O MADDER TARA SYM PL O C OS SUMA C SE Q UO I A MAR IG O L D SA FFL OWER B U CK THORN LIVI N G B L UE MYRO B A L AN K AMA L A L A C I ND IG O HENNA H I MA L AYAN RHU B AR B G A LL NUT WE L D P OME G RANATE L O G WOOD EASTERN B RA ZIL WOOD C UT C H C HAMOM IL E ( SA PP ANWOOD ) A LK ANET ON I ON S KI NS OSA G E C HESTNUT C O C H I NEA L Q UE B RA C HO EU P ATOR I UM $1.00 603216 NATURAL DYES WHAT THEY ARE AND HOW TO USE THEM Artisans have added colour to cloth for thousands of years. It is only recently (the first artificial dye was invented in 1857) that the textile industry has turned to synthetic dyes. Today, many craftspeople are rediscovering the joy of achieving colour through the use of renewable, non-toxic, natural sources. Natural dyes are inviting and satisfying to use. Most are familiar substances that will spark creative ideas and widen your view of the world. Try experimenting. Colour can be coaxed from many different sources. Once the cloth or fibre is prepared for dyeing it will soak up the colour, yielding a range of results from deep jew- el-like tones to dusky heathers and pastels. -

Against Expression?: Avant-Garde Aesthetics in Satie's" Parade"

Against Expression?: Avant-garde Aesthetics in Satie’s Parade A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2020 By Carissa Pitkin Cox 1705 Manchester Street Richland, WA 99352 [email protected] B.A. Whitman College, 2005 M.M. The Boston Conservatory, 2007 Committee Chair: Dr. Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract The 1918 ballet, Parade, and its music by Erik Satie is a fascinating, and historically significant example of the avant-garde, yet it has not received full attention in the field of musicology. This thesis will provide a study of Parade and the avant-garde, and specifically discuss the ways in which the avant-garde creates a dialectic between the expressiveness of the artwork and the listener’s emotional response. Because it explores the traditional boundaries of art, the avant-garde often resides outside the normal vein of aesthetic theoretical inquiry. However, expression theories can be effectively used to elucidate the aesthetics at play in Parade as well as the implications for expressability present in this avant-garde work. The expression theory of Jenefer Robinson allows for the distinction between expression and evocation (emotions evoked in the listener), and between the composer’s aesthetical goal and the listener’s reaction to an artwork. This has an ideal application in avant-garde works, because it is here that these two categories manifest themselves as so grossly disparate. -

CEU Department of Medieval Studies, 2001)

TABLE OF CONTENTS Editors’ Preface ............................................................................................................. 5 I. ARTICLES AND STUDIES .........................................................................7 Rozana Vojvoda Većenega’s ‘Book of Hours’: a Manuscript Study with Special Stress on Decorated Initials............................... 9 Ana Marinković Constrvi et erigi ivssit rex Collomannvs: The Royal Chapel of King Coloman in the Complex of St. Mary in Zadar........ 37 Jan Machula Foreign Items and Outside Influences in the Material Culture of Tenth-Century Bohemia................................................................................. 65 Ildikó Csepregi The Miracles of Saints Cosmas and Damian: Characteristics of Dream Healing ...................................................................... 89 Csaba Németh Videre sine speculo: The Immediate Vision of God in the Works of Richard of St. Victor..............123 Réka Forrai Text and Commentary: the Role of Translations in the Latin Tradition of Aristotle’s De anima (1120–1270).......................139 Dávid Falvay “A Lady Wandering in a Faraway Land” The Central European Queen/princess Motif in Italian Heretical Cults..........157 Lucie Doležalová “Reconstructing” the Bible: Strategies of Intertextuality in the Cena Cypriani...........................................181 Reading the Scripture ..............................................................................203 Foreword – Ottó Gecser ...............................................................................205 -

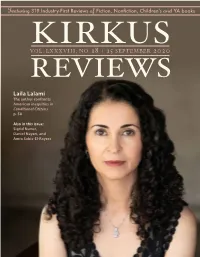

Kirkus Reviews on Our Website by Logging in As a Subscriber

Featuring 319 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books VOL.KIRKUS LXXXVIII, NO. 18 | 15 SEPTEMBER 2020 REVIEWS Laila Lalami The author confronts American inequities in Conditional Citizens p. 58 Also in this issue: Sigrid Nunez, Daniel Nayeri, and Amra Sabic-El-Rayess from the editor’s desk: The Way I Read Now Chairman BY TOM BEER HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # Among the many changes in my daily life this year—working from home, Chief Executive Officer wearing a mask in public, watching too much TV—my changing read- MEG LABORDE KUEHN ing habits register deeply. For one thing, I read on a Kindle now, with the [email protected] Editor-in-Chief exception of the rare galley sent to me at home and the books I’ve made TOM BEER a point of purchasing from local independent bookstores or ordering on [email protected] Vice President of Marketing Bookshop.org. The Kindle was borrowed—OK, confiscated—from my SARAH KALINA boyfriend at the beginning of the pandemic, when I left dozens of advance [email protected] reader copies behind at the office and accepted the reality that digital gal- Managing/Nonfiction Editor ERIC LIEBETRAU leys would be a practical necessity for the foreseeable future. I can’t say that I [email protected] love reading on my “new” Kindle—I’m still a sucker for physical books after Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK all these years—but I’ll admit that it fulfills its purpose efficiently. And I do [email protected] Tom Beer rather enjoy the instant gratification of going on NetGalley or Edelweiss Young Readers’ Editor VICKY SMITH and dispatching multiple books to my device in one fell swoop—a harmless [email protected] form of bingeing that affords a little dopamine rush. -

The Noble Families of Butovan and Botono in Medieval Zadar: Family Structure, Property Reconstruction, and Social Life1

929.52Butovan 929.52Botono 94(497.5Zadar)’’12/13’’ Primljeno: 22. 5. 2019. Prihvaćeno: 17. 6. 2019. Izvorni znanstveni rad DOI: 10.22586/pp.v56i1.9177 Sandra Begonja* Zrinka Nikolić Jakus** The Noble Families of Butovan and Botono in Medieval Zadar: Family Structure, Property Reconstruction, and Social Life1 This paper presents the genealogy (family structure), urban family estates, and social life of the Zadar-based noble families of Butovan and Botono during the 13th and 14th centuries (until the 1390s) in order to determine their similarities and differences (whether they were one or two different families). Research has been based on various types of sources, primarily published and unpublished archival material preserved at the State Archive in Zadar (notarial and court documents). Keywords: medieval Zadar, noble families, genealogies, urban and social history The Zadar-based families of Butovan and Botono have not yet been in the focus of detailed research, and their individual members have mostly been mentioned only in studies on Zadar’s nobility or general topics related to the city’s past. Mo- dern historians have differed in their opinions on whether these were two diffe- rent families or a single one whose name has been recorded in different ways.2 * Sandra Begonja, Croatian Institute of History, Opatička 10, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia, E-mail: phelgor@ yahoo.co.uk ** Zrinka Nikolić Jakus, Department of History, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb, Ivana Lučića 3, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia, E-mail: [email protected] 1 This study has been sponsored by the Croatian Science Foundation, project “Cities of the Croatian Middle Ages: Urban Elites and Urban Spaces (URBES), no. -

Isolation and Extraction of Ruberythric Acid from Rubia Tinctorum L. and Crystal Structure Elucidation

This is a repository copy of Isolation and extraction of ruberythric acid from Rubia tinctorum L. and crystal structure elucidation. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/87252/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Ford, L, Rayner, CM and Blackburn, RS (2015) Isolation and extraction of ruberythric acid from Rubia tinctorum L. and crystal structure elucidation. Phytochemistry, 117. 168 - 173. ISSN 0031-9422 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2015.06.015 © 2015, Elsevier. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Isolation and extraction of ruberythric acid from Rubia tinctorum L. and crystal structure elucidation Lauren Forda,b, Christopher M. -

Press Release

CONTACT: McKenna Young FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 484-385-2913 (office) December 17, 2015 [email protected] PRESS RELEASE Horatio Alger Association Announces 12 Recipients of Annual Dennis R. Washington Achievement Graduate Scholarships The Dennis & Phyllis Washington Foundation provides graduate grants of up to $90,000 to Horatio Alger Scholars who wish to further their education WASHINGTON, D.C. (December 17, 2015) – Horatio Alger Association of Distinguished Americans, Inc., a nonprofit educational organization honoring the achievements of outstanding individuals and encouraging youth to pursue their dreams through higher education, today announced the 12 recipients of the 2015 Dennis R. Washington Achievement Graduate Scholarship. Endowed in 2008 and funded by the Dennis & Phyllis Washington Foundation, this scholarship provides financial assistance to Alumni recipients of Horatio Alger National and State Scholarships who aspire to obtain graduate degrees. The Dennis & Phyllis Washington Foundation was established in 1988 by Dennis Washington, chairman emeritus of Horatio Alger Association, and his wife, Phyllis. Since its inception, the Foundation has donated more than $199 million to charitable causes. The Foundation, which supports deserving individuals in an effort to better society as a whole, established its Achievement Graduate Scholarship program to provide financial assistance exclusively to Horatio Alger undergraduate scholarship recipients who are committed to pursuing a graduate degree. Applicants must have a minimum 3.0 -

The Bear in Eurasian Plant Names

Kolosova et al. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine (2017) 13:14 DOI 10.1186/s13002-016-0132-9 REVIEW Open Access The bear in Eurasian plant names: motivations and models Valeria Kolosova1*, Ingvar Svanberg2, Raivo Kalle3, Lisa Strecker4,Ayşe Mine Gençler Özkan5, Andrea Pieroni6, Kevin Cianfaglione7, Zsolt Molnár8, Nora Papp9, Łukasz Łuczaj10, Dessislava Dimitrova11, Daiva Šeškauskaitė12, Jonathan Roper13, Avni Hajdari14 and Renata Sõukand3 Abstract Ethnolinguistic studies are important for understanding an ethnic group’s ideas on the world, expressed in its language. Comparing corresponding aspects of such knowledge might help clarify problems of origin for certain concepts and words, e.g. whether they form common heritage, have an independent origin, are borrowings, or calques. The current study was conducted on the material in Slavonic, Baltic, Germanic, Romance, Finno-Ugrian, Turkic and Albanian languages. The bear was chosen as being a large, dangerous animal, important in traditional culture, whose name is widely reflected in folk plant names. The phytonyms for comparison were mostly obtained from dictionaries and other publications, and supplemented with data from databases, the co-authors’ field data, and archival sources (dialect and folklore materials). More than 1200 phytonym use records (combinations of a local name and a meaning) for 364 plant and fungal taxa were recorded to help find out the reasoning behind bear-nomination in various languages, as well as differences and similarities between the patterns among them. Among the most common taxa with bear-related phytonyms were Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (L.) Spreng., Heracleum sphondylium L., Acanthus mollis L., and Allium ursinum L., with Latin loan translation contributing a high proportion of the phytonyms. -

Artist's Proposal

Gabbert Artist’s Proposal 14th Street Roundabout Page 434 of 1673 Gabbert Sarasota Roundabout 41&14th James Gabbert Sculptor Ladies and Gentlemen, Thank you for this opportunity. For your consideration I propose a work tentatively titled “Flame”. I believe it to be simple-yet- compelling, symbolic, and appropriate to this setting. Dimensions will be 20 feet high by 14.5 feet wide by 14.5 feet deep. It sits on a 3.5 feet high by 9 feet in diameter base. (not accurately dimensioned in the 3D graphics) The composition. The design has substance, and yet, there is practically no impediment to drivers’ visibility. After review of the design by a structural engineer the flame flicks may need to be pierced with openings to meet the 150 mph wind velocity requirement. I see no problem in adjusting the design to accommodate any change like this. Fire can represent our passions, zeal, creativity, and motivation. The “flame” can suggest the light held by the Statue of Liberty, the fire from Prometheus, the spirit of the city, and the hearth-fire of 612.207.8895 | jgsculpture.webs.com | [email protected] 14th Street Roundabout Page 435 of 1673 Gabbert Sarasota Roundabout 41&14th James Gabbert Sculptor home. It would be lit at night with a soft glow from within. A flame creates a sense of place because everyone is drawn to a fire. A flame sheds light and warmth. Reference my “Hopes and Dreams” in my work example to get a sense of what this would look like. The four circles suggest unity and wholeness, or, the circle of life, or, the earth/universe. -

Montana Billionaires Got $900 Million Richer Over First 10 Months of Pandemic, Their Collective Wealth Jumping by 7%

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE February 11, 2021 Montana Billionaires Got $900 Million Richer Over First 10 Months of Pandemic, Their Collective Wealth Jumping By 7% Gains of 4 Richest Residents Could Cover State’s $59 Million Budget Shortfall 15 Times Over & Still Leave Billionaires as Rich as They Were Before COVID Billings, MT—The collective wealth of Montana’s four billionaires jumped by $900 million, or 7%, between mid-March of last year and Jan. 29 of this year, according to a new report by Americans for Tax Fairness (ATF), Health Care for America Now (HCAN) and Big Sky 55+. The $900 million in pandemic profits of the state’s richest residents could cover the state’s projected $59 million 2021 budget gap 15 times over and still leave them as wealthy as they were when the pandemic started 10 months ago. Between March 18—the rough start date of the pandemic shutdown, when most federal and state economic restrictions were put in place—and Jan. 29, the total net worth of Montana billionaires rose from $12.9 billion to $13.8 billion, based on this analysis of Forbes data, and also shown in the table below.1 The private gain of Montana billionaires contrasts sharply with the health and economic struggles that average Montanans are facing because of the pandemic. Over those same tough 10 months, some 92,934 state residents fell ill with the coronavirus, 1,210 died from it and 200,669 lost jobs in the accompanying recession. While federal lawmakers debate more cash payments to people and families in the next relief package, the state’s four billionaires have amassed enough new wealth during the pandemic, a $900 million surge, to send every one of the state’s 1,068,778 residents a relief check of roughly $870 each.