The Noble Families of Butovan and Botono in Medieval Zadar: Family Structure, Property Reconstruction, and Social Life1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CEU Department of Medieval Studies, 2001)

TABLE OF CONTENTS Editors’ Preface ............................................................................................................. 5 I. ARTICLES AND STUDIES .........................................................................7 Rozana Vojvoda Većenega’s ‘Book of Hours’: a Manuscript Study with Special Stress on Decorated Initials............................... 9 Ana Marinković Constrvi et erigi ivssit rex Collomannvs: The Royal Chapel of King Coloman in the Complex of St. Mary in Zadar........ 37 Jan Machula Foreign Items and Outside Influences in the Material Culture of Tenth-Century Bohemia................................................................................. 65 Ildikó Csepregi The Miracles of Saints Cosmas and Damian: Characteristics of Dream Healing ...................................................................... 89 Csaba Németh Videre sine speculo: The Immediate Vision of God in the Works of Richard of St. Victor..............123 Réka Forrai Text and Commentary: the Role of Translations in the Latin Tradition of Aristotle’s De anima (1120–1270).......................139 Dávid Falvay “A Lady Wandering in a Faraway Land” The Central European Queen/princess Motif in Italian Heretical Cults..........157 Lucie Doležalová “Reconstructing” the Bible: Strategies of Intertextuality in the Cena Cypriani...........................................181 Reading the Scripture ..............................................................................203 Foreword – Ottó Gecser ...............................................................................205 -

Byzantium's Balkan Frontier

This page intentionally left blank Byzantium’s Balkan Frontier is the first narrative history in English of the northern Balkans in the tenth to twelfth centuries. Where pre- vious histories have been concerned principally with the medieval history of distinct and autonomous Balkan nations, this study regards Byzantine political authority as a unifying factor in the various lands which formed the empire’s frontier in the north and west. It takes as its central concern Byzantine relations with all Slavic and non-Slavic peoples – including the Serbs, Croats, Bulgarians and Hungarians – in and beyond the Balkan Peninsula, and explores in detail imperial responses, first to the migrations of nomadic peoples, and subsequently to the expansion of Latin Christendom. It also examines the changing conception of the frontier in Byzantine thought and literature through the middle Byzantine period. is British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow, Keble College, Oxford BYZANTIUM’S BALKAN FRONTIER A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, – PAUL STEPHENSON British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow Keble College, Oxford The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org © Paul Stephenson 2004 First published in printed format 2000 ISBN 0-511-03402-4 eBook (Adobe Reader) ISBN 0-521-77017-3 hardback Contents List ofmaps and figurespagevi Prefacevii A note on citation and transliterationix List ofabbreviationsxi Introduction .Bulgaria and beyond:the Northern Balkans (c.–) .The Byzantine occupation ofBulgaria (–) .Northern nomads (–) .Southern Slavs (–) .The rise ofthe west,I:Normans and Crusaders (–) . -

Reaction to the Siege of Zadar in Western Christendom

Vanja Burić REACTION TO THE SIEGE OF ZADAR IN WESTERN CHRISTENDOM MA Thesis in Medieval Studies CEU eTD Collection Central European University Budapest May 2015 REACTION TO THE SIEGE OF ZADAR IN WESTERN CHRISTENDOM by Vanja Burić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ Examiner Budapest CEU eTD Collection May 2015 i REACTION TO THE SIEGE OF ZADAR IN WESTERN CHRISTENDOM by Vanja Burić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2015 ii REACTION TO THE SIEGE OF ZADAR IN WESTERN CHRISTENDOM by Vanja Burić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Supervisor Budapest CEU eTD Collection May 2015 iii I, the undersigned, Vanja Burić, candidate for the MA degree in Medieval Studies, declare herewith that the present thesis is exclusively my own work, based on my research and only such external information as properly credited in notes and bibliography. I declare that no unidentified and illegitimate use was made of the work of others, and no part of the thesis infringes on any person’s or institution’s copyright. -

Croatian Regions, Cities-Communes, and Their Population in the Eastern Adriatic in the Travelogues of Medieval European Pilgrims

359 Croatian Regions, Cities-Communes, and Their Population in the Eastern Adriatic in the Travelogues of Medieval European Pilgrims Zoran Ladić In this article, based on the information gathered from a dozen medieval pilgrim travelogues and itineraries,1 my aim has been to indicate the attitudes, impressions, and experiences noted down by sometimes barely educated and at other times very erudite clerical and lay pilgrims, who travelled to the Holy Land and Jerusalem as palmieri or palmarii2 ultra mare and wrote about the geographical features of the Eastern Adriatic coast, its ancient and medieval monuments, urban structures, visits to Istrian and Dalmatian communes, contacts with the local population, encounters with the secular and spiritual customs and the language, the everyday behaviour of the locals, and so on. Such information is contained, to a greater or lesser extent, in their travelogues and journals.3 To be sure, this type of sources, especially when written by people who were prone to analyse the differences between civilizations and cultural features, are filled with their subjective opinions: fascination with the landscapes and cities, sacral and secular buildings, kindness of the local population, ancient monuments in urban centres, the abundance of relics, and the quality of 1 According to the research results of French historian Aryeh Graboïs, there are 135 preserved pilgrim journals of Western European provenance dating from the period between 1327 and 1498. Cf. Aryeh Graboïs, Le pèlerin occidental en Terre sainte au Moyen Âge (Paris and Brussels: De Boeck Université, 1998), 212-214. However, their number seems to be much larger: some have been published after Graboïs’s list, some have been left out, and many others are preserved at various European archives and libraries. -

Croatian and Czech Air Force Teams'joint Training

N O 8 YEA R 4 T OCO B E R 2 0 1 2 croatian air force CROATIAN AND CZECH AIR FORCE TEAMS’ JOINT TRAINING interview MAJOR GENERAL MICHAEL REPASS COMMANDER OF U.S. SPECIAL OPERATIONS COMMAND EUROPE, COMMANDER OF MILITARY EXERCISE JACKAL STONE 2012 special operations battalion THE COMMANDO TRAINING A DRILL ONLY FOR THE TOUGHEST internationalJACKAL special units’ military exercise STONE 12 the croatian military industry ĐURO ĐAKOVIĆ’S PRIMARY AMV 8X8 PILLAR OF DEVELOPMENT 01_naslovnica_08.indd 1 10/29/12 1:53 PM 2 OCTOBER 2012 CROMIL 02_03_sadrzaj.indd 2 10/29/12 1:57 PM Cover by Davor Kirin IN THIS ISSUE One of the many examples of the cooperation and joint work of special units, in this case the 11 countries that partici- 4 INTERVIEW pated in Jackal Stone 2012, is this year’s largest international special units’ military exercise in Europe. It was held in Croatia and proved that international forces can cooperate exceptionally well even when special units are concerned, and it was all for the strengthening of stability and safety in the world, which along with increasing cooperation and interoperability between countries participating in the exercise, was one of the main goals of the exercise MAJOR GENERAL MICHAEL REPASS, international special units’ military exercise Leida Parlov, photos by Davor Kirin, Josip Kopi COMMANDER OF U.S. SPECIAL OPERATIONS COMMAND EUROPE, COMMANDER OF MILITARY EXERCISE JACKAL STONE 2012 SPECIALISTS FROM 11 COUNTRIES AT 8 INTERNATIONAL SPECIAL UNITS’ MILITARY EXERCISE S PECIALISTS FROM 11 COUNTRIES AT JACKAL STONE 12 To successfully counter security threats in our present time, a proper collaboration between the special units of friendly and partner countries is necessary. -

Food Access and Conflict: Responsibility and Future Prosecution Guidelines for the Continued Humanitarian Violations of the Yemeni People

Food Access and Conflict: Responsibility and Future Prosecution Guidelines for the Continued Humanitarian Violations of the Yemeni People by Elizabeth Louise Evans A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in International Affairs Middle Tennessee State University December 2018 Thesis Committee: Dr. Stephen D. Morris, Chair Dr. Andrei Korobkov Dr. Moses Tesi I dedicate this to those who do not know the warmth of full stomach. I also dedicate this to my husband and children in the hope they pursue their interests looking through a global lens, act locally to create an peaceful atmosphere around them, and defend others rights to live the same, for they have never known hunger. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Completing this thesis required a lot of determination. Thankfully I had the right guidance and support. Throughout this process, many individuals supported me and helped make this thesis a reality. I wholeheartedly acknowledge the guidance and support from my supervisor, Dr. Stephen D. Morris. His experience and insightful direction focused me to be cognizant of the previously completed works in this area in order for this work to augment the literature. I am equally thankful to my secondary advisor Dr. Andrei Korobkov, whose astute direction as a professor afforded me a better understanding of the International Affairs. I also want to unequivocally thank Dr. Moses Tesi. His knowledge of international development spurred me to move out of my comfort zone and investigate an area of study I am passionate about. Lastly, I need to acknowledge my great friend Nicole F. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Templar and Hospitaller Periods

Levente Baján THE TRANSFORMATIONS OF VRANA FROM THE 12TH TO 14TH CENTURIES: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE TEMPLAR AND HOSPITALLER PERIODS MA Thesis in Comparative History, with a specialization in Interdisciplinary Medieval Studies CEU eTD Collection Central European University Budapest May 2018 THE TRANSFORMATIONS OF VRANA FROM THE 12TH TO 14TH CENTURIES: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE TEMPLAR AND HOSPITALLER PERIODS by Levente Baján (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Comparative History, with a specialization in Interdisciplinary Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ CEU eTD Collection Examiner THE TRANSFORMATIONS OF VRANA FROM THE 12TH TO 14TH CENTURIES: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE TEMPLAR AND HOSPITALLER PERIODS by Levente Baján (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Comparative History, with a specialization in Interdisciplinary Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2018 THE TRANSFORMATIONS OF VRANA FROM THE 12TH TO 14TH CENTURIES: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE TEMPLAR AND HOSPITALLER PERIODS by Levente Baján (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Comparative History, with a specialization in Interdisciplinary Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. -

Knjiga Sažetaka Zbornik Radova Petoga Hrvatskog Slavističkog Kongresa

ISBN: 978-953-296-181-2 7. HRVATSKI SLAVISTIČKI KONGRES - KNJIGA SAŽETAKA 9 789532 961812 ZBORNIK RADOVA PETOGA HRVATSKOG SLAVISTIČKOG KONGRESA Davor Nikolić Filozofski fakultet Sveučilišta u Zagrebu KAKO JE MILIVOJ SOLAR PRESTAO BITI “ZABAVAN” I POSTAO “TRIVIJALAN” (Književnoteorijski pomak M. Solara od termina zabavne prema terminu trivijalne književnosti) UDK Pregledni rad U ovom se radu prikazuje odnos jednog od najvažnijih hrvatskih književnih teoretičara Milivoja Solara prema terminu zabavne, odnosno trivijalne književnosti. Ova promišljanja možemo u širem smislu pratiti kroz sva Solarova djela, ali eksplicitno se ovim problemima bavio u četirima autorskim knjigama. Pregledom tih knjiga prikazat će se kako je autor pomaknuo svoj teorijski obzor s termina zabavne prema terminu trivijalne književnosti, ali i kako je došlo do promjene u izboru ključnih aspekata za određivanje statusa i naravi te i takve književnosti. Ključne riječi: zabavna književnost, trivijalna književnost, Milivoj Solar, recepcija 389 Impresum: Izdavač Hrvatsko filološko društvo Za izdavača Anita Skelin Horvat Uredili i priredili Ivica Baković Anđela Frančić Marija Malnar Jurišić Lana Molvarec Bernardina Petrović Grafičko oblikovanje Redak, Split . REPUBLIKA HRVATSKA HRVATSKO FILOLOŠKO DRUŠTVO HRVATSKI SLAVISTIČKI ODBOR SEDMI HRVATSKI SLAVISTIČKI KONGRES ŠIBENIK, 25. – 28. RUJNA 2019. KNJIGA SAŽETAKA Zagreb, 2019. Sadržaj Sadržaj 1. PALEOSLAVISTIČKA I HRVATSKOGLAGOLJSKA PROBLEMATIKA ......................................................................................................11 -

Trpimir Vedriš Reviving the Middle Ages in Croatia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Reti Medievali Open Archive Trpimir Vedriš Reviving the Middle Ages in Croatia [A stampa in Fifteen-Year Anniversary Reports, a cura di M. Sághy, “Annual of Medieval Studies at CEU” (Central European University, Budapest), ed. by J. A. Rasson and B. Zsolt Szakács, vol. 15 (2009), pp. 197-211 © dell’autore – Distribuito in formato digitale da “Reti Medievali”]. REVIVING THE MIDDLE AGES IN CROATIA* Trpimir Vedriš It is no exaggeration that the study of the Middle Ages has played a crucial role in the study of Croatian history since its establishment as an academic discipline in the second half of the nineteenth century.1 Th is special interest in medieval history, however, had little in common with what is nowadays called “medieval studies.” Research in Croatian medieval history, similarly to other countries in nineteenth- century Europe, was strongly linked to the process of nation building, which has been much discussed lately.2 One aspect of this legacy can serve as an appropriate point of departure here, namely, the factthat interest in the medieval period not only held the imagination of nineteenth-century Croatian “historian-politicians,” but also many (if not a majority) among the most prominent Croatian historians of the twentieth century were medievalists. With all the diff erences between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, medieval studies have always been “the most prominent and fruitful area of Croatian historiography.”3 Th e fall of Communism after 1989 and the fi nal dissolution of the multi- ethnic “fortress of socialism in the Balkans” during the war of 1991–1995 promised uncertain fortunes for Croatian history. -

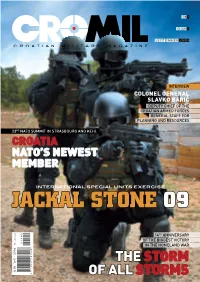

Jackal Stone 09

N O 2 Y E A R 1 S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 9 INTERVIEW COLONEL GENERAL SLAVKO BARIć DEPUTY CHIEF OF THE CRoatIAN ARMED FoRCES GENERAL StaFF FOR PLANNING AND RESOURCES 23RD NATO SUMMIT IN STRASBOURG AND KEHL CROATIA NATO’S NEWEST MEMBER INTERNATIONAL SPECIAL UNITS EXERCISE JACKAL STONE 09 14TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE BIGGEST VICtoRY IN THE HOMELAND WaR THE STORM OF ALL STORMS Cover by Davor Kirin IN THIS ISSUE THE GOAL OF THE EXERCISE as to practice hostage situation THE MINISTER BRANKO VUKELI∆ The goal of the exercise was to promote the procedures, to train liaison ““Only top professionals such as yourselves 4 INTERVIEW cooperation of participating countries in officers and to generally raise the can carry out what are probably the most the war against terrorism and to strengthen level of planning ability and the demanding tasks which can be entrusted regional security and stability, as well implementation of such activities to a soldier” COLONEL GENERAL SLAVKO BARIć, DEPUTY CHIEF OF THE military exercise by Leida Parlov, photos by Tomislav Brandt, Davor Kirin croatian military magazine INTERNATIONAL SPECIAL UNITS EXERCISE The Jackal Stone Exercise is the biggest training event since the Republic of Croatia’s entry into NATO and is also this year’s big- CROATIAN ARMED FORCES GENERAL STAFF FOR PLANNING gest special units exercise in Europe. Along with the host country Croatia, members of special units from Albania, Hungary, Lithu- ania, Macedonia, Poland, Romania, Sweden, the Ukraine and the Unites States participated in the exercise. Altogether there were AND RESOURCES JACKAL STONE 09 nearly 1500 participants. -

CEU Department of Medieval Studies in 2014/2015

ANNUAL OF MEDIEVAL STUDIES AT CEU VOL. 22 2016 Central European University Budapest ANNUAL OF MEDIEVAL STUDIES AT CEU VOL. 22 2016 Edited by Judith A. Rasson and Zsuzsanna Reed Central European University Budapest Department of Medieval Studies All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the permission of the publisher. Editorial Board Gerhard Jaritz, György Geréby, Gábor Klaniczay, József Laszlovszky, Judith A. Rasson, Marianne Sághy, Katalin Szende, Daniel Ziemann Editors Judith A. Rasson and Zsuzsanna Reed Technical Assistant Kyra Lyublyanovics Cover Illustration Copper coin of Béla III (1172–1196), CNH 101, Hungary. Pannonia Terra Numizmatika © (reproduced with permission) Department of Medieval Studies Central European University H-1051 Budapest, Nádor u. 9., Hungary Postal address: H-1245 Budapest 5, P.O. Box 1082 E-mail: [email protected] Net: http://medievalstudies.ceu.edu Copies can be ordered at the Department, and from the CEU Press http://www.ceupress.com/order.html Volumes of the Annual are available online at: http://www.library.ceu.hu/ams/ ISSN 1219-0616 Non-discrimination policy: CEU does not discriminate on the basis of—including, but not limited to—race, color, national or ethnic origin, religion, gender or sexual orientation in administering its educational policies, admissions policies, scholarship and loan programs, and athletic and other school-administered programs. © Central European University Produced by Archaeolingua Foundation & Publishing House TABLE OF CONTENTS Editors’ preface ............................................................................................................ 5 I. ARTICLES AND STUDIES ........................................................... 7 Johanna Rákos-Zichy To Bury and to Praise: The Late Antique Bishop at His Parents’ Grave .............................................. -

NHBB 2017 National History Bee National Championships Round 1

reached). +8: REACHING and SCORING: INSTRUCTIONS: Tournament Student namesStudent ( Total pts for +8 reaching full name Moderator circle it Cross remainder out of row student’s and For correct answers, place new running total in student’s row for the corresponding question. For -1’s (3 for question. corresponding the row student’s in total running For correct new place answers, . Cross out entire columnCross entire out Remove student from round. In “Final score” column, place student’s total score (refer to the bottom row for the question on which +8 was Remove from was student +8 score” score “Final (referwhich column, In total on round. bottom student’s forplace to the question the row school include ) 1 2 3 NATIONAL HISTORY BEE: Round 1 Round BEE: HISTORY NATIONAL 15 points 15 ifscore no change. 4 5 6 . 7 8 9 14 Make column scoresplace sure the to in forcorrect the question 10 11 13 12 Scorer 13 12 pts 14 15 16 17 11 points 11 18 19 Room 20 21 22 10 points 10 23 24 25 rd incorrect interrupt), place running total total running place incorrect interrupt), 26 Round 27 9 points . 28 29 30 31 (circle 1) Division 32 8 points 33 34 V 35 score JV Final Final NHBB Nationals Bee 2016-2017 Bee Round 1 Bee Round 1 Regulation Questions (1) An employee of this company, Conrad Ahlers, was illegally arrested at the behest of the German consulate while vacationing in Madrid. Rudolf Augstein was the owner of this company when it conducted research into the preparedness of military forces during a NATO exercise.