The Bear in Eurasian Plant Names

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary Composer Vladimir Jovanović and His Role in the Renewal of Church Byzantine Music in Serbia from the 1990S Until Today

Interdisciplinary Studies in Musicology 19, 2019 @PTPN Poznań 2019, DOI 10.14746/ism.2019.19.1 GORDANA BLAGOJEVIĆ https://orcid.org/0000–0001–7883–8071 Institute of Ethnography SASA, Belgrade Contemporary composer Vladimir Jovanović and his role in the renewal of church Byzantine music in Serbia from the 1990s until today ABSTRACT: This work focuses on the role of the composer Vladimir (Vlada) Jovanović in the rene- wal of church Byzantine music in Serbia from the 1990s until today. This multi-talented artist wor- ked and created art in his native Belgrade, with creativity that exceeded local frames. This research emphasizes Jovanović’s pedagogical and compositional work in the field of Byzantine music, which mostly took place through his activity in the St. John of Damascus choir in Belgrade. The author analyzes the problems in implementation of modal church Byzantine music, since the first students did not hear it in their surroundings, as well as the responses of the listeners. Special attention is paid to students’ narratives, which help us perceive the broad cultural and social impact of Jovanović’s creative work. KEYWORDS: composer Vladimir (Vlada) Jovanović, church Byzantine music, modal music, St. John of Damascus choir. Introduction This work was written in commemoration of a contemporary Serbian composer1 Vladimir Jovanović (1956–2016) with special reference to his role in the renewal of church Byzantine music in Serbia from the beginning of the 1990s until today.2 In the text we refer to Vladimir Jovanović as Vlada – a shortened form of his name, which relatives, friends, colleagues and students used most of- ten in communication with the composer, as an expression of sincere closeness. -

Globalna Strategija Ohranjanja Rastlinskih

GLOBALNA STRATEGIJA OHRANJANJA RASTLINSKIH VRST (TOČKA 8) UNIVERSITY BOTANIC GARDENS LJUBLJANA AND GSPC TARGET 8 HORTUS BOTANICUS UNIVERSITATIS LABACENSIS, SLOVENIA INDEX SEMINUM ANNO 2017 COLLECTORUM GLOBALNA STRATEGIJA OHRANJANJA RASTLINSKIH VRST (TOČKA 8) UNIVERSITY BOTANIC GARDENS LJUBLJANA AND GSPC TARGET 8 Recenzenti / Reviewers: Dr. sc. Sanja Kovačić, stručna savjetnica Botanički vrt Biološkog odsjeka Prirodoslovno-matematički fakultet, Sveučilište u Zagrebu muz. svet./ museum councilor/ dr. Nada Praprotnik Naslovnica / Front cover: Semeska banka / Seed bank Foto / Photo: J. Bavcon Foto / Photo: Jože Bavcon, Blanka Ravnjak Urednika / Editors: Jože Bavcon, Blanka Ravnjak Tehnični urednik / Tehnical editor: D. Bavcon Prevod / Translation: GRENS-TIM d.o.o. Elektronska izdaja / E-version Leto izdaje / Year of publication: 2018 Kraj izdaje / Place of publication: Ljubljana Izdal / Published by: Botanični vrt, Oddelek za biologijo, Biotehniška fakulteta UL Ižanska cesta 15, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenija tel.: +386(0) 1 427-12-80, www.botanicni-vrt.si, [email protected] Zanj: znan. svet. dr. Jože Bavcon Botanični vrt je del mreže raziskovalnih infrastrukturnih centrov © Botanični vrt Univerze v Ljubljani / University Botanic Gardens Ljubljana ----------------------------------- Kataložni zapis o publikaciji (CIP) pripravili v Narodni in univerzitetni knjižnici v Ljubljani COBISS.SI-ID=297076224 ISBN 978-961-6822-51-0 (pdf) ----------------------------------- 1 Kazalo / Index Globalna strategija ohranjanja rastlinskih vrst (točka 8) -

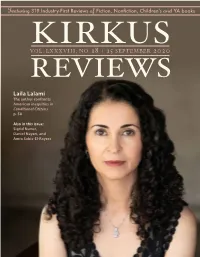

Kirkus Reviews on Our Website by Logging in As a Subscriber

Featuring 319 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books VOL.KIRKUS LXXXVIII, NO. 18 | 15 SEPTEMBER 2020 REVIEWS Laila Lalami The author confronts American inequities in Conditional Citizens p. 58 Also in this issue: Sigrid Nunez, Daniel Nayeri, and Amra Sabic-El-Rayess from the editor’s desk: The Way I Read Now Chairman BY TOM BEER HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # Among the many changes in my daily life this year—working from home, Chief Executive Officer wearing a mask in public, watching too much TV—my changing read- MEG LABORDE KUEHN ing habits register deeply. For one thing, I read on a Kindle now, with the [email protected] Editor-in-Chief exception of the rare galley sent to me at home and the books I’ve made TOM BEER a point of purchasing from local independent bookstores or ordering on [email protected] Vice President of Marketing Bookshop.org. The Kindle was borrowed—OK, confiscated—from my SARAH KALINA boyfriend at the beginning of the pandemic, when I left dozens of advance [email protected] reader copies behind at the office and accepted the reality that digital gal- Managing/Nonfiction Editor ERIC LIEBETRAU leys would be a practical necessity for the foreseeable future. I can’t say that I [email protected] love reading on my “new” Kindle—I’m still a sucker for physical books after Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK all these years—but I’ll admit that it fulfills its purpose efficiently. And I do [email protected] Tom Beer rather enjoy the instant gratification of going on NetGalley or Edelweiss Young Readers’ Editor VICKY SMITH and dispatching multiple books to my device in one fell swoop—a harmless [email protected] form of bingeing that affords a little dopamine rush. -

Sinopsis De La Familia Acanthaceae En El Perú

Revista Forestal del Perú, 34 (1): 21 - 40, (2019) ISSN 0556-6592 (Versión impresa) / ISSN 2523-1855 (Versión electrónica) © Facultad de Ciencias Forestales, Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina, Lima-Perú DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21704/rfp.v34i1.1282 Sinopsis de la familia Acanthaceae en el Perú A synopsis of the family Acanthaceae in Peru Rosa M. Villanueva-Espinoza1, * y Florangel M. Condo1 Recibido: 03 marzo 2019 | Aceptado: 28 abril 2019 | Publicado en línea: 30 junio 2019 Citación: Villanueva-Espinoza, RM; Condo, FM. 2019. Sinopsis de la familia Acanthaceae en el Perú. Revista Forestal del Perú 34(1): 21-40. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21704/rfp.v34i1.1282 Resumen La familia Acanthaceae en el Perú solo ha sido revisada por Brako y Zarucchi en 1993, desde en- tonces, se ha generado nueva información sobre esta familia. El presente trabajo es una sinopsis de la familia Acanthaceae donde cuatro subfamilias (incluyendo Avicennioideae) y 38 géneros son reconocidos. El tratamiento de cada género incluye su distribución geográfica, número de especies, endemismo y carácteres diagnósticos. Un total de ocho nombres (Juruasia Lindau, Lo phostachys Pohl, Teliostachya Nees, Streblacanthus Kuntze, Blechum P. Browne, Habracanthus Nees, Cylindrosolenium Lindau, Hansteinia Oerst.) son subordinados como sinónimos y, tres especies endémicas son adicionadas para el país. Palabras clave: Acanthaceae, actualización, morfología, Perú, taxonomía Abstract The family Acanthaceae in Peru has just been reviewed by Brako and Zarruchi in 1993, since then, new information about this family has been generated. The present work is a synopsis of family Acanthaceae where four subfamilies (includying Avicennioideae) and 38 genera are recognized. -

Piano Di Gestione Del Sic/Zps It3310001 “Dolomiti Friulane”

Piano di Gestione del SIC/ZPS IT 3310001 “Dolomiti Friulane” – ALLEGATO 2 PIANO DI GESTIONE DEL SIC/ZPS IT3310001 “DOLOMITI FRIULANE” ALLEGATO 2 ELENCO DELLE SPECIE FLORISTICHE E SCHEDE DESCRITTIVE DELLE SPECIE DI IMPORTANZA COMUNITARIA Agosto 2012 Responsabile del Piano : Ing. Alessandro Bardi Temi Srl Piano di Gestione del SIC/ZPS IT 3310001 “Dolomiti Friulane” – ALLEGATO 2 Classe Sottoclasse Ordine Famiglia Specie 1 Lycopsida Lycopodiatae Lycopodiales Lycopodiaceae Huperzia selago (L.)Schrank & Mart. subsp. selago 2 Lycopsida Lycopodiatae Lycopodiales Lycopodiaceae Diphasium complanatum (L.) Holub subsp. complanatum 3 Lycopsida Lycopodiatae Lycopodiales Lycopodiaceae Lycopodium annotinum L. 4 Lycopsida Lycopodiatae Lycopodiales Lycopodiaceae Lycopodium clavatum L. subsp. clavatum 5 Equisetopsida Equisetatae Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum arvense L. 6 Equisetopsida Equisetatae Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum hyemale L. 7 Equisetopsida Equisetatae Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum palustre L. 8 Equisetopsida Equisetatae Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum ramosissimum Desf. 9 Equisetopsida Equisetatae Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum telmateia Ehrh. 10 Equisetopsida Equisetatae Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum variegatum Schleich. ex Weber & Mohr 11 Polypodiopsida Polypodiidae Polypodiales Adiantaceae Adiantum capillus-veneris L. 12 Polypodiopsida Polypodiidae Polypodiales Hypolepidaceae Pteridium aquilinum (L.)Kuhn subsp. aquilinum 13 Polypodiopsida Polypodiidae Polypodiales Cryptogrammaceae Phegopteris connectilis (Michx.)Watt -

Cirsium Vulgare Gewöhnliche Kratzdistel

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Brandes Dietmar_diverse botanische Arbeiten Jahr/Year: 2011 Band/Volume: 111_2011 Autor(en)/Author(s): Brandes Dietmar Artikel/Article: Disteln in Osttirol 1-47 © Dietmar Brandes; download unter http://www.ruderal-vegetation.de/epub/index.html und www.zobodat.at Platzhalter für Bild, Bild auf Titelfolie hinter das Logo einsetzen Disteln in Osttirol Prof. Dr. Dietmar Brandes 7.10.2011 © Dietmar Brandes; download unter http://www.ruderal-vegetation.de/epub/index.html und www.zobodat.at Disteln • Zu den Arten der Unterfamilie Carduae der Familie Asteraceae gehören weltweit ca. 2.500 Arten (Heywood et al. 2007). Hierzu werden die mehr oder minder bedornten Arten v.a. der Gattungen Carduus, Carlina, Carthamus, Cirsium, Cynara, Echinops, Onopordum und Silybum gerechnet. • Die Distelartigen haben ihr Mannigfaltigkeitszentrum in Zentralasien sowie im angrenzenden Europa. Ihre Bewehrung wird zumeist als Schutz gegen Herbivorenfraß interpretiert. So kommen die meisten Distelarten Osttirols entweder in überweideten Pflanzengesellschaften unterschiedlichster Art oder aber auf Ruderalflächen vor. • Zu den einzelnen Arten werden grundlegende Angaben zur ihrer Ökologie und Phytozönologie gemacht; die meisten Arten wurden in Osttirol am Standort fotografiert. © Dietmar Brandes; download unter http://www.ruderal-vegetation.de/epub/index.html und www.zobodat.at Disteln in Osttirol • Carduus acanthoides, Carduus -

Flora of Deepdale 2020

Flora of Deepdale 2020 John Durkin MSC. MCIEEM www.durhamnature.co.uk [email protected] Introduction Deepdale is a side valley of the River Tees, joining the Tees at Barnard Castle. Its moorland catchment area is north of the A66 road across the Pennines. The lower three miles of the dale is a steep-sided rocky wooded valley. The nature reserve includes about half of this area. Deepdale has been designated as a Local Wildlife Site by Durham County Council. Deepdale is one of four large (more than 100 hectare) woods in Teesdale. These are important landscape-scale habitat features which I have termed “Great Woods”. The four Teesdale Great Woods are closely linked to each other, and are predominantly “ancient semi-natural” woods, both of these features increasing their value for wildlife. The other three Teesdale Great Woods are the Teesbank Woods upstream of Barnard Castle to Eggleston, the Teesbank Woods downstream from Barnard Castle to Gainford, and the woods along the River Greta at Brignall Banks. The habitats and wildlife of the Teesdale four are largely similar, with each having its particular distinctiveness. The Teesbank Woods upstream of Barnard Castle have been described in a booklet “A guide to the Natural History of the Tees Bank Woods between Barnard Castle and Cotherstone” by Margaret Morton and Margaret Bradshaw. Most of these areas have been designated as Local Wildlife Sites. Two areas, “Shipley and Great Wood” near Eggleston, and most of Brignall Banks have the higher designation, “Site of Special Scientific Interest”. There are about 22 Great Woods in County Durham, mainly in the well- wooded Derwent Valley, with four along the River Wear, three large coastal denes and the four in Teesdale. -

Switzerland - Alpine Flowers of the Upper Engadine

Switzerland - Alpine Flowers of the Upper Engadine Naturetrek Tour Report 8 - 15 July 2018 Androsace alpina Campanula cochlerariifolia The group at Piz Palu Papaver aurantiacum Report and Images by David Tattersfield Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Switzerland - Alpine Flowers of the Upper Engadine Tour participants: David Tattersfield (leader) with 16 Naturetrek clients Day 1 Sunday 8th July After assembling at Zurich airport, we caught the train to Zurich main station. Once on the intercity express, we settled down to a comfortable journey, through the Swiss countryside, towards the Alps. We passed Lake Zurich and the Walensee, meeting the Rhine as it flows into Liectenstein, and then changed to the UNESCO World Heritage Albula railway at Chur. Dramatic scenery and many loops, tunnels and bridges followed, as we made our way through the Alps. After passing through the long Preda tunnel, we entered a sunny Engadine and made a third change, at Samedan, for the short ride to Pontresina. We transferred to the hotel by minibus and met the remaining two members of our group, before enjoying a lovely evening meal. After a brief talk about the plans for the week, we retired to bed. Day 2 Monday 9th July After a 20-minute walk from the hotel, we caught the 9.06am train at Surovas. We had a scenic introduction to the geography of the region, as we travelled south along the length of Val Bernina, crossing the watershed beside Lago Bianco and alighting at Alp Grum. -

Recent Publications in Music 2009

Fontes Artis Musicae, Vol. 56/4 (2009) RECENT PUBLICATIONS IN MUSIC R1 RECENT PUBLICATIONS IN MUSIC 2009 On behalf of the International Association of Music Libraries Archives and Documentation Centres / Pour le compte l'Association Internationale des Bibliothèques, Archives et Centres de Documentation Musicaux / Im Auftrag der Die Internationale Vereinigung der Musikbibliotheken, Musikarchive und Musikdokumentationszentren This list contains citations to literature about music in print and other media, emphasizing reference materials and works of research interest that appeared in 2008. Reporters who contribute regularly provide citations mainly or only from the year preceding the year this list is published in the IAML journal Fontes Artis Musicae. However, reporters may also submit retrospective lists cumulating publications from up to the previous five years. In the hope that geographic coverage of this list can be expanded, the compiler welcomes inquiries from bibliographers in countries not presently represented. Compiled and edited by Geraldine E. Ostrove Reporters: Austria: Thomas Leibnitz Canada: Marlene Wehrle China, Hong Kong, Taiwan: Katie Lai Croatia: Zdravko Blaţeković Czech Republic: Pavel Kordík Estonia: Katre Rissalu Finland: Ulla Ikaheimo, Tuomas Tyyri France: Cécile Reynaud Germany: Wolfgang Ritschel Ghana: Santie De Jongh Greece: Alexandros Charkiolakis Hungary: Szepesi Zsuzsanna Iceland: Bryndis Vilbergsdóttir Ireland: Roy Stanley Italy: Federica Biancheri Japan: Sekine Toshiko Namibia: Santie De Jongh The Netherlands: Joost van Gemert New Zealand: Marilyn Portman Russia: Lyudmila Dedyukina South Africa: Santie De Jongh Spain: José Ignacio Cano, Maria José González Ribot Sweden Turkey: Paul Alister Whitehead, Senem Acar United States: Karen Little, Liza Vick. With thanks for assistance with translations and transcriptions to Kersti Blumenthal, D. -

C-Banding Patterns in Eighteen Taxa of the Genus Paris Sensu Li, Liliaceae

_??_1992 The Japan Mendel Society Cytologia 57: 181-194, 1992 C-banding Patterns in Eighteen Taxa of the Genus Paris sensu Li, Liliaceae Junko Miyamoto1, Siro Kurita1, Gu Zhilian2 and Li Hen2 1 Department of Biology , Faculty of Science, Chiba University, Japan 2 Kunming Institute of Botany , Academy of Science of China, Kunming, Yunnan, China Accepted October 31, 1991 Paris is a perennial genus distributed from Europe to the Far East . Most species, how ever, are restricted to Asia, excepting a European species P. quadrifolia Linnaeus and a Cau casian species P. incompleta M. -Bieberstein. Hara (1969) studied morphological variation in seven species: P. delavayi Franchet; P. incomplete M. -Bieberstein; P. japonica (Franch . et Sav.) Franchet; P. polyphylla Smith; P. quadrifolia Linnaeus; P. tetraphylla A. Gray; and P. verticillata M. -Bieberstein. Takhtajan (1983) founded a new genus Daiswa for all taxa of Papolyphylla complex, but Li (1988) degraded this to the subgeneric level. The historical back ground of Paris taxonomy and the synonymy of each taxon were summarized by Mitchell (1987, 1988). Karyomorphological studies on Japanese species were carried out by various authors (Gotoh 1933, Haga 1934, 1942, Hara 1969, Kayano 1961, Kurabayashi 1952, Kurabayashi and Samejima 1953, Miyamoto and Kurita 1990, Miyamoto et al. 1991, Noda 1963, Stow 1953, Suzuki and Yoshimura 1986). The standard chromosome numbers reported by these authors are 2n=10 (2X) in P. teteraphylla and P. verticillata and 2n=40 (8X) in P. japonica. The only European species, P. quadrifolia, was examined by many authors (Tischler 1934, Gotoh 1937, Geitler 1938, Darlington 1941, Love and Love 1944, Polya 1950, Skalinska et al. -

ACANTHACEAE 爵床科 Jue Chuang Ke Hu Jiaqi (胡嘉琪 Hu Chia-Chi)1, Deng Yunfei (邓云飞)2; John R

ACANTHACEAE 爵床科 jue chuang ke Hu Jiaqi (胡嘉琪 Hu Chia-chi)1, Deng Yunfei (邓云飞)2; John R. I. Wood3, Thomas F. Daniel4 Prostrate, erect, or rarely climbing herbs (annual or perennial), subshrubs, shrubs, or rarely small trees, usually with cystoliths (except in following Chinese genera: Acanthus, Blepharis, Nelsonia, Ophiorrhiziphyllon, Staurogyne, and Thunbergia), isophyllous (leaf pairs of equal size at each node) or anisophyllous (leaf pairs of unequal size at each node). Branches decussate, terete to angular in cross-section, nodes often swollen, sometimes spinose with spines derived from reduced leaves, bracts, and/or bracteoles. Stipules absent. Leaves opposite [rarely alternate or whorled]; leaf blade margin entire, sinuate, crenate, dentate, or rarely pinnatifid. Inflo- rescences terminal or axillary spikes, racemes, panicles, or dense clusters, rarely of solitary flowers; bracts 1 per flower or dichasial cluster, large and brightly colored or minute and green, sometimes becoming spinose; bracteoles present or rarely absent, usually 2 per flower. Flowers sessile or pedicellate, bisexual, zygomorphic to subactinomorphic. Calyx synsepalous (at least basally), usually 4- or 5-lobed, rarely (Thunbergia) reduced to an entire cupular ring or 10–20-lobed. Corolla sympetalous, sometimes resupinate 180º by twisting of corolla tube; tube cylindric or funnelform; limb subactinomorphic (i.e., subequally 5-lobed) or zygomorphic (either 2- lipped with upper lip subentire to 2-lobed and lower lip 3-lobed, or rarely 1-lipped with 3 lobes); lobes ascending or descending cochlear, quincuncial, contorted, or open in bud. Stamens epipetalous, included in or exserted from corolla tube, 2 or 4 and didyna- mous; filaments distinct, connate in pairs, or monadelphous basally via a sheath (Strobilanthes); anthers with 1 or 2 thecae; thecae parallel to perpendicular, equally inserted to superposed, spherical to linear, base muticous or spurred, usually longitudinally dehis- cent; staminodes 0–3, consisting of minute projections or sterile filaments. -

Research of the Biodiversity of Tovacov Lakes

Research of the biodiversity of Tovacov lakes (Czech Republic) Main researcher: Jan Ševčík Research group: Vladislav Holec Ondřej Machač Jan Ševčík Bohumil Trávníček Filip Trnka March – September 2014 Abstract We performed biological surveys of different taxonomical groups of organisms in the area of Tovacov lakes. Many species were found: 554 plant species, 107 spider species, 27 dragonflies, 111 butterfly species, 282 beetle species, orthopterans 17 and 7 amphibian species. Especially humid and dry open habitats and coastal lake zones were inhabited by many rare species. These biotopes were found mainly at the places where mining residuals were deposited or at the places which were appropriately prepared for mining by removing the soil to the sandy gravel base (on conditions that the biotope was still in contact with water level and the biotope mosaic can be created at the slopes with low inclination and with different stages of ecological succession). Field study of biotope preferences of the individual species from different places created during mining was performed using phytosociological mapping and capture traps. Gained data were analyzed by using ordinate analyses (DCA, CCA). Results of these analyses were interpreted as follows: Technically recultivated sites are quickly getting species – homogenous. Sites created by ecological succession are species-richer during their development. Final ecological succession stage (forest) can be achieved in the same time during ecological succession as during technical recultivation. According to all our research results most biologically valuable places were selected. Appropriate management was suggested for these places in order to achieve not lowering of their biological diversity. To even improve their biological diversity some principles and particular procedures were formulated.