Chapter 5 Writing Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Release Notes for Fedora 20

Fedora 20 Release Notes Release Notes for Fedora 20 Edited by The Fedora Docs Team Copyright © 2013 Fedora Project Contributors. The text of and illustrations in this document are licensed by Red Hat under a Creative Commons Attribution–Share Alike 3.0 Unported license ("CC-BY-SA"). An explanation of CC-BY-SA is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/. The original authors of this document, and Red Hat, designate the Fedora Project as the "Attribution Party" for purposes of CC-BY-SA. In accordance with CC-BY-SA, if you distribute this document or an adaptation of it, you must provide the URL for the original version. Red Hat, as the licensor of this document, waives the right to enforce, and agrees not to assert, Section 4d of CC-BY-SA to the fullest extent permitted by applicable law. Red Hat, Red Hat Enterprise Linux, the Shadowman logo, JBoss, MetaMatrix, Fedora, the Infinity Logo, and RHCE are trademarks of Red Hat, Inc., registered in the United States and other countries. For guidelines on the permitted uses of the Fedora trademarks, refer to https:// fedoraproject.org/wiki/Legal:Trademark_guidelines. Linux® is the registered trademark of Linus Torvalds in the United States and other countries. Java® is a registered trademark of Oracle and/or its affiliates. XFS® is a trademark of Silicon Graphics International Corp. or its subsidiaries in the United States and/or other countries. MySQL® is a registered trademark of MySQL AB in the United States, the European Union and other countries. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. -

Complete Letters Pdf Free Download

COMPLETE LETTERS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Pliny the Younger,P. G. Walsh | 432 pages | 15 Jun 2009 | Oxford University Press | 9780199538942 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom Complete Letters PDF Book Namespaces Article Talk. Also there are many extra notes explaining the contents of the letters, along with description of history events that may coincide with a letter. Very few examples of this form of written Old English have survived, mostly as short inscriptions or fragments. Actually, I read this edition of Wilde's letters when it was reissued a couple of years back. You must be logged in to post a comment. Main article: English phonology. Informal English writing tends to omit diacritics because of their absence from the keyboard, while professional copywriters and typesetters tend to include them. Letterhead and envelope. I'm honestly wishing the Oscar Wilde trial never happened, he never married. They show who he truly was, a genius, but with weaknesses like all human beings, a very sensitive soul. Evie Dunmore on Writing a Suffragist Romance. In fact, it was a very peppered plethora of letters to people that fell into the following categories: 1. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Spelling alphabets such as the ICAO spelling alphabet , used by aircraft pilots, police and others, are designed to eliminate this potential confusion by giving each letter a name that sounds quite different from any other. Complaint letter about overbooked flight. Letter to Santa. The letter Y sometimes represents a consonant as in "young" and sometimes a vowel as in "myth". Like helium or neon 7 Little Words. -

From Semantics to Dialectometry

Contents Preface ix Subjunctions as discourse markers? Stancetaking on the topic ‘insubordi- nate subordination’ Werner Abraham Two-layer networks, non-linear separation, and human learning R. Harald Baayen & Peter Hendrix John’s car repaired. Variation in the position of past participles in the ver- bal cluster in Duth Sjef Barbiers, Hans Bennis & Lote Dros-Hendriks Perception of word stress Leonor van der Bij, Dicky Gilbers & Wolfgang Kehrein Empirical evidence for discourse markers at the lexical level Jelke Bloem Verb phrase ellipsis and sloppy identity: a corpus-based investigation Johan Bos 7 7 Om-omission Gosse Bouma 8 Neural semantics Harm Brouwer, Mathew W. Crocker & Noortje J. Venhuizen 7 9 Liberating Dialectology J. K. Chambers 8 0 A new library for construction of automata Jan Daciuk 9 Generating English paraphrases from logic Dan Flickinger 99 Contents Use and possible improvement of UNESCO’s Atlas of the World’s Lan- guages in Danger Tjeerd de Graaf 09 Assessing smoothing parameters in dialectometry Jack Grieve 9 Finding dialect areas by means of bootstrap clustering Wilbert Heeringa 7 An acoustic analysis of English vowels produced by speakers of seven dif- ferent native-language bakgrounds Vincent J. van Heuven & Charlote S. Gooskens 7 Impersonal passives in German: some corpus evidence Erhard Hinrichs 9 7 In Hülle und Fülle – quantiication at a distance in German, Duth and English Jack Hoeksema 9 8 he interpretation of Duth direct speeh reports by Frisian-Duth bilin- guals Franziska Köder, J. W. van der Meer & Jennifer Spenader 7 9 Mining for parsing failures Daniël de Kok & Gertjan van Noord 8 0 Looking for meaning in names Stasinos Konstantopoulos 9 Second thoughts about the Chomskyan revolution Jan Koster 99 Good maps William A. -

Learning to Read and Spell Single Words: a Case Study of a Slavic Language

Learning to read and spell single words: a case study of a Slavic language. Marcin Szczerbiriski A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University College London August 2001 ProQuest Number: U643611 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U643611 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT We now have a good knowledge of the initial period of literacy acquisition in English, but the development of literacy in other languages, and the implication of this for our understanding of cognitive processing of written language, is less well explored. In this study, Polish T* - 3'*^ grade children (7;6-9;6 years old) were tested on reading and spelling of words, with controls for factors which have been shown to affect performance in other languages (lexicality, frequency, orthographic complexity). Moreover, each participant was individually tested on a range of linguistic skills understood to be essential components of literacy acquisition. These included: phonological awareness (detection, analysis, blending, deletion and replacement of sound segments in words) serial naming (of pictures, digits, letters) and morphological skills (using prefixes and suffixes). -

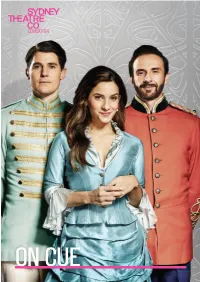

On Cue Table of Contents

ON CUE TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT ON CUE AND STC 2 CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS 3 CAST AND CREATIVES 4 FROM THE DIRECTOR 5 ABOUT THE PLAYWRIGHT 6 ABOUT THE PLAY 8 CONTEXT 9 SYNOPSIS 10 CHARACTER ANALYSIS 12 THEMES AND IDEAS 16 THE ELEMENTS OF DRAMA 20 STYLE 22 DESIGN 23 BIBLIOGRAPHY 24 Compiled by Hannah Brown. The activities and resources contained © Copyright protects this Education in this document are designed for Resource. educators as the starting point for Except for purposes permitted by the developing more comprehensive lessons Copyright Act, reproduction by whatever for this production. Hannah Brown means in prohibited. However, limited is the Education Projects Officers for photocopying for classroom use only is the Sydney Theatre Company. You can permitted by educational institutions. contact Hannah on [email protected] 1 ABOUT ON CUE AND STC ABOUT ON CUE STC Ed has a suite of resources located on our website to enrich and strengthen teaching and learning surrounding the plays in the STC season. Each show will be accompanied by an On Cue e-publication which will feature all the essential information for teachers and students, such as curriculum links, information about the playwright, synopsis, character analysis, thematic analysis and suggested learning experiences. For more in-depth digital resources surrounding the ELEMENTS OF DRAMA, DRAMATIC FORMS, STYLES, CONVENTIONS and TECHNIQUES, visit the STC Ed page on our website. SUCH RESOURCES INCLUDE: • videos • design sketchbooks • worksheets • posters ABOUT SYDNEY THEATRE COMPANY In 1980, STC’s first Artistic Director Richard Wherrett defined areas; and reaches beyond NSW with touring productions STC’s mission as to provide “first class theatrical entertainment throughout Australia. -

Polish Katarzyna DZIUBALSKA-KOŁACZYK and 1 Bogdan WALCZAK ( )

Polish Katarzyna DZIUBALSKA-KOŁACZYK and 1 Bogdan WALCZAK ( ) 1. The identity 1.1. The name In the 10th century, individual West Slavic languages were differentiated from the western group, Polish among others. The name of the language comes from the name of a tribe of Polans (Polanie) who inhabited the midlands of the river Warta around Gniezno and Poznań, and whose tribal state later became the germ of the Polish state. Etymologically, Polanie means ‘the inhabitants of fields’. The Latin sources provide also other forms of the word: Polanii, Polonii, Poloni (at the turn of the 10th and 11th century king Bolesław Chrobry was referred to as dux Poloniorum in The Life of St. Adalbert [Żywot św. Wojciecha]) (cf. Klemensiewicz : 1961-1972). 1.2. The family affiliation 1.2.1. Origin The Polish language is most closely related to the extinct Polabian- Pomeranian dialects (whose only live representative is Kashubian) and together with them is classified by Slavicists into the West Lechitic subgroup of the Slavic languages. It is less closely related to the remaining West Slavic languages, i.e. Slovak, Czech and High- and Low Sorbian, and still less closely to the East and (1) Katarzyna Dziubalska-Kołaczyk (School of English at Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań) is Professor of English linguistics and Head of the School. She has published extensively on phonology and phonetics, first and second language acquisition and morphology, in all the areas emphasizing the contrastive aspect (especially with Polish, but also other languages, e.g. German, Italian). She has taught Polish linguistics at the University of Vienna. -

Latgalian, a Short Grammar of (Nau).Pdf

Languages of the World/Materials 482 A short grammar of Latgal ian Nicole Nau full text research abstracts of all titles monthly updates 2011 LINCOM EUROPA LATGALIAN LW/M482 Published by LINCOM GmbH 2011. Contents Preface ............................................................................................................................ 3 LINCOMGmbH 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 4 Gmunder Str. 35 J .1 General information .................................................................................................. 4 D-81379 Muenchen 1.2 History ....................................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Research and description ........................................................................................... 7 [email protected] 1.4 Typological overview ................................................................................................ 8 www.lincom-europa.com 2. The sound system ..................................................................................................... 9 2. 1 Phonemes, sounds, and letters ................................................................................... 9 webshop: www.lincom-shop.eu 2.2 Stress and tone ......................................................................................................... 13 2.3 Phonological processes .......................................................................................... -

Orthographies in Early Modern Europe

Orthographies in Early Modern Europe Orthographies in Early Modern Europe Edited by Susan Baddeley Anja Voeste De Gruyter Mouton An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org ISBN 978-3-11-021808-4 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-021809-1 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-021806-2 ISSN 0179-0986 e-ISSN 0179-3256 ThisISBN work 978-3-11-021808-4 is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License, ase-ISBN of February (PDF) 978-3-11-021809-1 23, 2017. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-021806-2 LibraryISSN 0179-0986 of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ae-ISSN CIP catalog 0179-3256 record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. ISBN 978-3-11-028812-4 e-ISBNBibliografische 978-3-11-028817-9 Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliogra- fie;This detaillierte work is licensed bibliografische under the DatenCreative sind Commons im Internet Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs über 3.0 License, Libraryhttp://dnb.dnb.deas of February of Congress 23, 2017.abrufbar. -

1 Vivian Cook and Benedetta Bassetti Over the Past Ten Years, Literacy In

1 CHAPTER 1: AN INTRODUCTION TO RESEARCHING SECOND LANGUAGE WRITING SYSTEMS Vivian Cook and Benedetta Bassetti Over the past ten years, literacy in the second language has emerged as a significant topic of inquiry in research into language processes and educational policy. This book provides an overview of the emerging field of Second Language Writing Systems (L2WS) research, written by researchers with a wide range of interests, languages and backgrounds, who give a varied picture of how second language reading and writing relates to characteristics of writing systems (WSs), and who address fundamental questions about the relationships between bilingualism, biliteracy and writing systems. It brings together different disciplines with their own theoretical and methodological insights – cognitive, linguistic, educational and social factors of reading – and it contains both research reports and theoretical papers. It will interest a variety of readers in different areas of psychology, education, linguistics and second language acquisition research. 1. What this book is about Vast numbers of people all over the world are using or learning a second language writing system. According to the British Council (1999), a billion people are learning English as a Second Language, and perhaps as many are using it for science, business and travel. Yet English is only one of the second languages in wide-spread use, although undoubtedly the largest. For many of these people – whether students, scientists or computer users browsing the internet – the ability to read and write the second language is the most important skill. The learning of a L2 writing system is in a sense distinct from learning the language and is by no means an easy task in itself, say for Chinese people learning to read and write English, or for the reverse case of English people learning to read and write Chinese. -

Angol-Magyar Nyelvészeti Szakszótár

PORKOLÁB - FEKETE ANGOL- MAGYAR NYELVÉSZETI SZAKSZÓTÁR SZERZŐI KIADÁS, PÉCS 2021 Porkoláb Ádám - Fekete Tamás Angol-magyar nyelvészeti szakszótár Szerzői kiadás Pécs, 2021 Összeállították, szerkesztették és tördelték: Porkoláb Ádám Fekete Tamás Borítóterv: Porkoláb Ádám A tördelés LaTeX rendszer szerint, az Overleaf online tördelőrendszerével készült. A felhasznált sablon Vel ([email protected]) munkája. https://www.latextemplates.com/template/dictionary A szótárhoz nyújtott segítő szándékú megjegyzéseket, hibajelentéseket, javaslatokat, illetve felajánlásokat a szótár hagyományos, nyomdai úton történő előállítására vonatkozóan az [email protected] illetve a [email protected] e-mail címekre várjuk. Köszönjük szépen! 1. kiadás Szerzői, elektronikus kiadás ISBN 978-615-01-1075-2 El˝oszóaz els˝okiadáshoz Üdvözöljük az Olvasót! Magyar nyelven már az érdekl˝od˝oközönség hozzáférhet német–magyar, orosz–magyar nyelvészeti szakszótárakhoz, ám a modern id˝ok tudományos világnyelvéhez, az angolhoz még nem készült nyelvészeti célú szak- szótár. Ennek a több évtizedes hiánynak a leküzdésére vállalkoztunk. A nyelvtudo- mány rohamos fejl˝odéseés differenciálódása tovább sürgette, hogy elkészítsük az els˝omagyar-angol és angol-magyar nyelvészeti szakszótárakat. Jelen kötetben a kétnyelv˝unyelvészeti szakszótárunk angol-magyar részét veheti kezébe az Olvasó. Tervünk azonban nem el˝odöknélküli vállalkozás: tudomásunk szerint két nyelvészeti csoport kísérelt meg a miénkhez hasonló angol-magyar nyelvészeti szakszótárat létrehozni. Az els˝opróbálkozás -

Spelling Reform, English, Main Efforts Behind It 1875To2000

Some of the Main Efforts to Reform English Spelling from 1875 to 2000 1876: Teachers’ group initiates proposal for government inquiry into spelling reform; submitted by school boards in early 1878 1876: Spelling Reform Association founded in the US 1879: British Spelling Reform Association founded Late 1870s to mid–1890s: Attempts in the US to enact legislation to implement reformed spellings 1880 –► on: The Philological Society present sets of simplified spellings 1906: Simplified Spelling Board founded in the US 1906: US President Teddy Roosevelt implements use of Spelling Board’s set of simpler spellings ; this order is later overridden and rescinded 1908: The English Spelling Society founded in the UK (as the Simplified Spelling Society) 1923, 1926, and 1933: Simplified Spelling Society appeal to British Board of Education to consider reformed spelling Mid-1930s: Simplified Spelling Society develop ‘Nue Speling’ which spells all words phonemically 1934 to 1975: Chicago Tribune use small set of reformed spellings as standard in their newspaper 1946: US Spelling Reform Association and Simplified Spelling Board merge to become the Simpler Spelling Association ( this leading to a group known as American Literacy Council by end of 20th century ) 1949 and 1953: Bills introduced into British Parliament on looking into and instituting reformed spellings ; 1st defeated, 2nd withdrawn but leads to use of the Initial Teaching Alphabet in some schools 1958: Contest held, in accordance with part of George Bernard Shaw’s will, to design a new phonetic -

The Development of Writing and Preliterate Societies

The development of writing and preliterate societies Author: Cynthia Tung Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:107209 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2015 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. The development of writing and preliterate societies Cynthia Tung Advisor: MJ Connolly Program in Linguistics Slavic and Eastern Languages Department Boston College April 2015 Abstract This paper explores the question of script choice for a preliterate society deciding to write their language down for the first time through an exposition on types of writing systems and a brief history of a few writing systems throughout the world. Societies sometimes invented new scripts, sometimes adapted existing ones, and other times used a combination of both these techniques. Based on the covered scripts ranging from Mesopotamia to Asia to Europe to the Americas, I identify factors that influence the script decision including neighboring scripts, access to technology, and the circumstances of their introduction to writing. Much of the world uses the Roman alphabet and I present the argument that almost all preliterate societies beginning to write will choose to use a version of the Roman alphabet. However, the alphabet does not fit all languages equally well, and the paper closes out withan investigation into some of these inadequacies and how languages might resolve these issues. Contents 1 Introduction 5 2 What is writing? 6 2.1 Definition . 6 2.2 Types of writing . 6 2.2.1 Pictograms, logograms, and ideograms .