Spelling Reform, English, Main Efforts Behind It 1875To2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Release Notes for Fedora 20

Fedora 20 Release Notes Release Notes for Fedora 20 Edited by The Fedora Docs Team Copyright © 2013 Fedora Project Contributors. The text of and illustrations in this document are licensed by Red Hat under a Creative Commons Attribution–Share Alike 3.0 Unported license ("CC-BY-SA"). An explanation of CC-BY-SA is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/. The original authors of this document, and Red Hat, designate the Fedora Project as the "Attribution Party" for purposes of CC-BY-SA. In accordance with CC-BY-SA, if you distribute this document or an adaptation of it, you must provide the URL for the original version. Red Hat, as the licensor of this document, waives the right to enforce, and agrees not to assert, Section 4d of CC-BY-SA to the fullest extent permitted by applicable law. Red Hat, Red Hat Enterprise Linux, the Shadowman logo, JBoss, MetaMatrix, Fedora, the Infinity Logo, and RHCE are trademarks of Red Hat, Inc., registered in the United States and other countries. For guidelines on the permitted uses of the Fedora trademarks, refer to https:// fedoraproject.org/wiki/Legal:Trademark_guidelines. Linux® is the registered trademark of Linus Torvalds in the United States and other countries. Java® is a registered trademark of Oracle and/or its affiliates. XFS® is a trademark of Silicon Graphics International Corp. or its subsidiaries in the United States and/or other countries. MySQL® is a registered trademark of MySQL AB in the United States, the European Union and other countries. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. -

Complete Letters Pdf Free Download

COMPLETE LETTERS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Pliny the Younger,P. G. Walsh | 432 pages | 15 Jun 2009 | Oxford University Press | 9780199538942 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom Complete Letters PDF Book Namespaces Article Talk. Also there are many extra notes explaining the contents of the letters, along with description of history events that may coincide with a letter. Very few examples of this form of written Old English have survived, mostly as short inscriptions or fragments. Actually, I read this edition of Wilde's letters when it was reissued a couple of years back. You must be logged in to post a comment. Main article: English phonology. Informal English writing tends to omit diacritics because of their absence from the keyboard, while professional copywriters and typesetters tend to include them. Letterhead and envelope. I'm honestly wishing the Oscar Wilde trial never happened, he never married. They show who he truly was, a genius, but with weaknesses like all human beings, a very sensitive soul. Evie Dunmore on Writing a Suffragist Romance. In fact, it was a very peppered plethora of letters to people that fell into the following categories: 1. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Spelling alphabets such as the ICAO spelling alphabet , used by aircraft pilots, police and others, are designed to eliminate this potential confusion by giving each letter a name that sounds quite different from any other. Complaint letter about overbooked flight. Letter to Santa. The letter Y sometimes represents a consonant as in "young" and sometimes a vowel as in "myth". Like helium or neon 7 Little Words. -

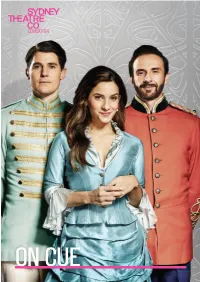

On Cue Table of Contents

ON CUE TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT ON CUE AND STC 2 CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS 3 CAST AND CREATIVES 4 FROM THE DIRECTOR 5 ABOUT THE PLAYWRIGHT 6 ABOUT THE PLAY 8 CONTEXT 9 SYNOPSIS 10 CHARACTER ANALYSIS 12 THEMES AND IDEAS 16 THE ELEMENTS OF DRAMA 20 STYLE 22 DESIGN 23 BIBLIOGRAPHY 24 Compiled by Hannah Brown. The activities and resources contained © Copyright protects this Education in this document are designed for Resource. educators as the starting point for Except for purposes permitted by the developing more comprehensive lessons Copyright Act, reproduction by whatever for this production. Hannah Brown means in prohibited. However, limited is the Education Projects Officers for photocopying for classroom use only is the Sydney Theatre Company. You can permitted by educational institutions. contact Hannah on [email protected] 1 ABOUT ON CUE AND STC ABOUT ON CUE STC Ed has a suite of resources located on our website to enrich and strengthen teaching and learning surrounding the plays in the STC season. Each show will be accompanied by an On Cue e-publication which will feature all the essential information for teachers and students, such as curriculum links, information about the playwright, synopsis, character analysis, thematic analysis and suggested learning experiences. For more in-depth digital resources surrounding the ELEMENTS OF DRAMA, DRAMATIC FORMS, STYLES, CONVENTIONS and TECHNIQUES, visit the STC Ed page on our website. SUCH RESOURCES INCLUDE: • videos • design sketchbooks • worksheets • posters ABOUT SYDNEY THEATRE COMPANY In 1980, STC’s first Artistic Director Richard Wherrett defined areas; and reaches beyond NSW with touring productions STC’s mission as to provide “first class theatrical entertainment throughout Australia. -

1 Vivian Cook and Benedetta Bassetti Over the Past Ten Years, Literacy In

1 CHAPTER 1: AN INTRODUCTION TO RESEARCHING SECOND LANGUAGE WRITING SYSTEMS Vivian Cook and Benedetta Bassetti Over the past ten years, literacy in the second language has emerged as a significant topic of inquiry in research into language processes and educational policy. This book provides an overview of the emerging field of Second Language Writing Systems (L2WS) research, written by researchers with a wide range of interests, languages and backgrounds, who give a varied picture of how second language reading and writing relates to characteristics of writing systems (WSs), and who address fundamental questions about the relationships between bilingualism, biliteracy and writing systems. It brings together different disciplines with their own theoretical and methodological insights – cognitive, linguistic, educational and social factors of reading – and it contains both research reports and theoretical papers. It will interest a variety of readers in different areas of psychology, education, linguistics and second language acquisition research. 1. What this book is about Vast numbers of people all over the world are using or learning a second language writing system. According to the British Council (1999), a billion people are learning English as a Second Language, and perhaps as many are using it for science, business and travel. Yet English is only one of the second languages in wide-spread use, although undoubtedly the largest. For many of these people – whether students, scientists or computer users browsing the internet – the ability to read and write the second language is the most important skill. The learning of a L2 writing system is in a sense distinct from learning the language and is by no means an easy task in itself, say for Chinese people learning to read and write English, or for the reverse case of English people learning to read and write Chinese. -

Angol-Magyar Nyelvészeti Szakszótár

PORKOLÁB - FEKETE ANGOL- MAGYAR NYELVÉSZETI SZAKSZÓTÁR SZERZŐI KIADÁS, PÉCS 2021 Porkoláb Ádám - Fekete Tamás Angol-magyar nyelvészeti szakszótár Szerzői kiadás Pécs, 2021 Összeállították, szerkesztették és tördelték: Porkoláb Ádám Fekete Tamás Borítóterv: Porkoláb Ádám A tördelés LaTeX rendszer szerint, az Overleaf online tördelőrendszerével készült. A felhasznált sablon Vel ([email protected]) munkája. https://www.latextemplates.com/template/dictionary A szótárhoz nyújtott segítő szándékú megjegyzéseket, hibajelentéseket, javaslatokat, illetve felajánlásokat a szótár hagyományos, nyomdai úton történő előállítására vonatkozóan az [email protected] illetve a [email protected] e-mail címekre várjuk. Köszönjük szépen! 1. kiadás Szerzői, elektronikus kiadás ISBN 978-615-01-1075-2 El˝oszóaz els˝okiadáshoz Üdvözöljük az Olvasót! Magyar nyelven már az érdekl˝od˝oközönség hozzáférhet német–magyar, orosz–magyar nyelvészeti szakszótárakhoz, ám a modern id˝ok tudományos világnyelvéhez, az angolhoz még nem készült nyelvészeti célú szak- szótár. Ennek a több évtizedes hiánynak a leküzdésére vállalkoztunk. A nyelvtudo- mány rohamos fejl˝odéseés differenciálódása tovább sürgette, hogy elkészítsük az els˝omagyar-angol és angol-magyar nyelvészeti szakszótárakat. Jelen kötetben a kétnyelv˝unyelvészeti szakszótárunk angol-magyar részét veheti kezébe az Olvasó. Tervünk azonban nem el˝odöknélküli vállalkozás: tudomásunk szerint két nyelvészeti csoport kísérelt meg a miénkhez hasonló angol-magyar nyelvészeti szakszótárat létrehozni. Az els˝opróbálkozás -

The Development of Writing and Preliterate Societies

The development of writing and preliterate societies Author: Cynthia Tung Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:107209 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2015 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. The development of writing and preliterate societies Cynthia Tung Advisor: MJ Connolly Program in Linguistics Slavic and Eastern Languages Department Boston College April 2015 Abstract This paper explores the question of script choice for a preliterate society deciding to write their language down for the first time through an exposition on types of writing systems and a brief history of a few writing systems throughout the world. Societies sometimes invented new scripts, sometimes adapted existing ones, and other times used a combination of both these techniques. Based on the covered scripts ranging from Mesopotamia to Asia to Europe to the Americas, I identify factors that influence the script decision including neighboring scripts, access to technology, and the circumstances of their introduction to writing. Much of the world uses the Roman alphabet and I present the argument that almost all preliterate societies beginning to write will choose to use a version of the Roman alphabet. However, the alphabet does not fit all languages equally well, and the paper closes out withan investigation into some of these inadequacies and how languages might resolve these issues. Contents 1 Introduction 5 2 What is writing? 6 2.1 Definition . 6 2.2 Types of writing . 6 2.2.1 Pictograms, logograms, and ideograms . -

Six New Letters for a Reformed Alphabet Nicola Twilley

Six New Letters for a Reformed Alphabet Nicola Twilley Type is always on a sliding scale of ephemerality, rendered impermanent by its substrate, medium, or message. Even if the words are considered worth saving – and in that distinction, we’ve already lost a large percentage of all typographic material – digital type is trapped in its storage medium, lead is melted down, paper thins and yellows, ink fades, and stone is eroded. The technologies of type evolve and decay. Type is the building material of written language, and language itself – if it has a self – is a system in constant motion: shedding skins of dead words; borrowing words from other languages; inventing words to reflect its users’ habits and needs. Type is built on the foundation of a writing system, from the building blocks listed in an alphabet. Here, at the level of the alphabet itself, we have surely reached bedrock: it is the stable and unchanging essence of all letters, the referent for all pieces of type… In fact, alphabetical solidity is nothing more than a temporal effect: if we could use time-lapse photography to revisit the development of the 26-letter Latin alphabet used to transcribe English, we’d see that letters have been discarded, added, and reshaped almost beyond recognition. The alphabet itself is malleable, temporary, subject to reform and revision. In this paper, I present the alphabet reforms suggested by Benjamin Franklin, using them to uncover the multiple motivations of alphabet visionaries past and present. A founding father, diplomat, printer, scientist, writer, and civic reformer, Franklin’s achievements include charting the Gulf Stream, writing the most widely published autobiography of all time, and introducing rhubarb and the soybean to the US. -

Complete Issue 25:0 As One

TEX Users Group PREPRINTS for the 2004 Annual Meeting TEX Users Group Board of Directors These preprints for the 2004 annual meeting are Donald Knuth, Grand Wizard of TEX-arcana † ∗ published by the TEX Users Group. Karl Berry, President Kaja Christiansen∗, Vice President Periodical-class postage paid at Portland, OR, and ∗ Sam Rhoads , Treasurer additional mailing offices. Postmaster: Send address ∗ Susan DeMeritt , Secretary changes to T X Users Group, 1466 NW Naito E Barbara Beeton Parkway Suite 3141, Portland, OR 97209-2820, Jim Hefferon U.S.A. Ross Moore Memberships Arthur Ogawa 2004 dues for individual members are as follows: Gerree Pecht Ordinary members: $75. Steve Peter Students/Seniors: $45. Cheryl Ponchin The discounted rate of $45 is also available to Michael Sofka citizens of countries with modest economies, as Philip Taylor detailed on our web site. Raymond Goucher, Founding Executive Director † Membership in the TEX Users Group is for the Hermann Zapf, Wizard of Fonts † calendar year, and includes all issues of TUGboat ∗member of executive committee for the year in which membership begins or is †honorary renewed, as well as software distributions and other benefits. Individual membership is open only to Addresses Electronic Mail named individuals, and carries with it such rights General correspondence, (Internet) and responsibilities as voting in TUG elections. For payments, etc. General correspondence, membership information, visit the TUG web site: TEX Users Group membership, subscriptions: http://www.tug.org. P. O. Box 2311 [email protected] Portland, OR 97208-2311 Institutional Membership U.S.A. Submissions to TUGboat, Institutional Membership is a means of showing Delivery services, letters to the Editor: continuing interest in and support for both TEX parcels, visitors [email protected] and the TEX Users Group. -

An Alphabet for English-IV. PUB DATE 2000-02-25 NOTE 15P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 438 554 CS 217 010 AUTHOR Crown, J. Conrad TITLE An Alphabet for English-IV. PUB DATE 2000-02-25 NOTE 15p. PUB TYPE Guides - Non-Classroom (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Alphabets; Elementary Education; Phonetics; Spelling; *Written Language ABSTRACT The current spelling of words in English is so lacking in consistency that the time is ripe for the adoption of an alphabet that embodies some semblance of phonetics. This paper proposes a new alphabet for English that uses the English (Roman) letters as elements so that current type and typewriters can still be used. Furthermore, allowance is made to distinguish the great number of homonyms that occur in the English language. The new alphabet is presented in four stages, starting with an Initial Teaching Alphabet, then adding successively alternate vowels, consonant modifications, and finally special letter strings. (Author/RS) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. 1 AN ALPHABET FOR ENGLISH-IV © By J. Conrad Crown, Ph.D. Professor Emeritus of Mathematical Sciences Indiana UniversityPurdue University at Indianapolis ABSTRACT The current spelling of words in English is so lacking in consistency that the time is ripe for the adaption of an alphabet that embodies some semblance of phonetics. The present study was undertaken with this in mind. A new alphabet for English is proposed that uses the English (Roman) letters as elements so that current type and typewriters can still be used. Furthermore and, perhaps more important, allowance is made to distinguish the great number of homonyms that occur in the English language. -

ED377446.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 377 446 CS 011 908 AUTHOR Albert, Elaine TITLE How Does It Feel To Begin To Learn To Read? PUB DATE 94 NOTE 3p. PUB TYPE Viewpoints (Opinion/Position Papers, Essays, etc.) (120) Reports Descriptive (141) Historic. .1 Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PCO1 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Beginning Reading; *Initial Teaching Alphabet; *Phonics; Primary Education; *Reading Instruction; Reading Research; *Reading Strategies IDENTIFIERS Historical Background; Shaw (George Bernard) ABSTRACT A reading instructor interested in reliving the experience of learning to read for the first time attempted to read "Androcles and the Lion" in Shavian Alphabet. The would-be reader of Shavian faces a page of hooks and slants completely unfamiliar, but there is no translation problem. As soon as the reader can pronounce out loud the sounds represented by these hooks, he hears himself reading English. In several aspects, this experience parallels that of the first-grader learning to read: (1) it involves an unknown code, the Shavian alphabet;(2) once the correct sound for the symbol is made, it is like reading in an individual's mother tongue;(3) it is hard work; and (4) Shavian presents a lot of trouble with reversals such as "b" and "d." Learning to read in Shavian suggests how much easier it eight be to learn to read in English if the alphabet more accurately reflected the sounds in the language. By 1961, British schools were trying out a new alphabet developed by Sir James Pitman called the Initial Teaching Alphabet (i/t/a/), which uses the Roman alphabet along with some additional letters. -

Guide to Shavian Spelling

GUIDE July, 1963 TO SHAVIAN SPELLING, by 4fy»(UyK**<L The phonetic Shavian Alphabet tempts us to delight in spelling precisely as we happen to speak. This involves spelling the same word in different ways according to local pronunciation, personal habit, formality or informality, context of words preceding and following, or degree of emphasis. To be able to render all these oddities and subleties as we write is very fascinating, and at first hardly to be discouraged. But we read far more than we write; and we try each other*« patience if reading is not made easy. Fast reading cannot wait to analyse the sound of every letter: we should lose grasp of the sentence and of its sense. The *look" of each word must Instantly suffice, and it will do so only when varied spellings are avoided. So Shavian readers of three months' standing are more than ready as writers to adopt agreed spellings. That the spellings are arbitrary matters little so long as they are instantly recognized. If this GUIDE is followed with understanding and care, our differences of spelling will drop to 6, 5 or 4 letters in 1,000 letters (I.e., in about 300 words). We shall write with less hesitation. The hindrance to reading wixl be ended. ANDR0CLES AND THE LION is at present our only example of consistent spelling. On that example this GUIDE is based, with a few alternatives added after close study of Shavian correspondence from U.S.A., Canada, Britain and Australia. Apart from occasional slips with consonants, spelling difficulties lie in the correct use of vowel letters. -

5 Bulgarian (15 Marks) Here Are Some Bulgarian Noun Phrases in the Form ‘Quantifier’ (I.E

tall deep 1 s z 2 f v Assuming that the same pattern applies to other letters, what do you think is the Shavian symbol for our letter ‘b’? 5 Bulgarian (15 marks) Here are some Bulgarian noun phrases in the form ‘quantifier’ (i.e. numeral or “many”) + noun. • dvama uchenici - two students • devet garderoba - nine wardrobes • mnogo uchenici - many students • edin sand ək - one chest • tri sand əka - three chests • mnogo sand əci - many chests • devetima bal əci - nine morons • mnogo garderobi - many wardrobes • shestima programisti - six programmers • chetiri kapaka - four covers • mnogo programisti - many programmers • trima chistachi - three cleaners • edin bal ək - one moron Note: Bulgarian normally uses the Cyrillic alphabet (as in български език ), but this problem uses the Roman alphabet instead, with c for a "ts" sound and ə for the sound at the end of sofa . Otherwise, the letters sound as in English. Question 5. Translate the following into Bulgarian: 1. six covers 2. many morons 3. four cleaners 4. many covers 5. one programmer 6. three students 6 4s The Shavian Alphabet (10 marks) The author G.B. Shaw (author of Pygmalion , which became the musical My Fair Lady ) saw the use of the Latin (or Roman) alphabet for English as a waste of time – the alphabet simply was not suited to write English. He left money in his will to the inventor of a new (and better) script for English. Kingsley Read, among many others, entered the competition, and his alphabet was chosen in 1958 as the best response to Shaw’s challenge.