Language Ideologies and Orthographies: Developing a Writing System for Than Ówîngeh Evan Ashworth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Release Notes for Fedora 20

Fedora 20 Release Notes Release Notes for Fedora 20 Edited by The Fedora Docs Team Copyright © 2013 Fedora Project Contributors. The text of and illustrations in this document are licensed by Red Hat under a Creative Commons Attribution–Share Alike 3.0 Unported license ("CC-BY-SA"). An explanation of CC-BY-SA is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/. The original authors of this document, and Red Hat, designate the Fedora Project as the "Attribution Party" for purposes of CC-BY-SA. In accordance with CC-BY-SA, if you distribute this document or an adaptation of it, you must provide the URL for the original version. Red Hat, as the licensor of this document, waives the right to enforce, and agrees not to assert, Section 4d of CC-BY-SA to the fullest extent permitted by applicable law. Red Hat, Red Hat Enterprise Linux, the Shadowman logo, JBoss, MetaMatrix, Fedora, the Infinity Logo, and RHCE are trademarks of Red Hat, Inc., registered in the United States and other countries. For guidelines on the permitted uses of the Fedora trademarks, refer to https:// fedoraproject.org/wiki/Legal:Trademark_guidelines. Linux® is the registered trademark of Linus Torvalds in the United States and other countries. Java® is a registered trademark of Oracle and/or its affiliates. XFS® is a trademark of Silicon Graphics International Corp. or its subsidiaries in the United States and/or other countries. MySQL® is a registered trademark of MySQL AB in the United States, the European Union and other countries. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. -

Complete Letters Pdf Free Download

COMPLETE LETTERS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Pliny the Younger,P. G. Walsh | 432 pages | 15 Jun 2009 | Oxford University Press | 9780199538942 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom Complete Letters PDF Book Namespaces Article Talk. Also there are many extra notes explaining the contents of the letters, along with description of history events that may coincide with a letter. Very few examples of this form of written Old English have survived, mostly as short inscriptions or fragments. Actually, I read this edition of Wilde's letters when it was reissued a couple of years back. You must be logged in to post a comment. Main article: English phonology. Informal English writing tends to omit diacritics because of their absence from the keyboard, while professional copywriters and typesetters tend to include them. Letterhead and envelope. I'm honestly wishing the Oscar Wilde trial never happened, he never married. They show who he truly was, a genius, but with weaknesses like all human beings, a very sensitive soul. Evie Dunmore on Writing a Suffragist Romance. In fact, it was a very peppered plethora of letters to people that fell into the following categories: 1. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Spelling alphabets such as the ICAO spelling alphabet , used by aircraft pilots, police and others, are designed to eliminate this potential confusion by giving each letter a name that sounds quite different from any other. Complaint letter about overbooked flight. Letter to Santa. The letter Y sometimes represents a consonant as in "young" and sometimes a vowel as in "myth". Like helium or neon 7 Little Words. -

Piller Language-Ideologies.Pdf

Language Ideologies INGRID PILLER Macquarie University, Australia Many people from around the world are likely to agree on the following: English is the most useful language for global commercial, scientific, and cultural exchange. The best kind of English is spoken by native speakers, particularly those from the United King- dom and the United States of America, and everyone else should try to emulate their English. American English sounds professional and competent, while African Ameri- can English sounds streetwise and cool and Indian English sounds nerdy and funny. While most readers will recognize these commonsense assumptions about English as a global language, it is also easy to see that they are nothing more than beliefs and feelings and that they are impossible to confirm or refute. This is most obvious in the case of value judgments about accents: Whether you think that Indian English is funny or not depends on who you are and what your experiences with Indian English are. If you are a speaker of Indian English, it is unlikely that you consider it funny; conversely, if you regularly interact with Indian speakers of English, you are unlikely to find the way they talk funny. On the other hand, if your main exposure to Indian English is through the character of Apu in the animated television series The Simpsons,youarelikelyto find Indian English very funny. While it is relatively easy to see through the idea that “Indian English is funny,” it is a bit more difficult to question some of the other assumptions in the introductory example, such as its many language names: The meaning of terms like “English,” “Amer- icanEnglish,”“AfricanAmericanEnglish,”or“IndianEnglish”isnotasstraightforward as it may seem. -

20 LANGUAGE IDEOLOGY AS a CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK to ANALYZE ISSUES RELATED to LANGUAGE POLICY and LANGUAGE EDUCATION Valentina

Revista Científica de la Facultad de Filosofía – UNA (ISSN: 2414-8717) Vol. 6, enero-julio 2018 (1), pp. 20-42. LANGUAGE IDEOLOGY AS A CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK TO ANALYZE ISSUES RELATED TO LANGUAGE POLICY AND LANGUAGE EDUCATION Valentina Canese1 Abstract This article discusses how the notions of language ideology and language ideologies may be used as analytical tools to examine issues related to language policy and language education. First of all, it provides an overview of language ideology as a field of study. Following, it presents a discussion of language ideology in language policy and planning as well as language teaching. Subsequently, the article presents an overview of how language ideology may be used in research methodology as a conceptual framework to analyze issues related to language in education providing examples of how these concepts have been applied by different authors including this article‘s author. The article concludes that the notions presented may be powerful tools to be applied with caution as biases derived from our own positioning of members of a nation or a linguistic group may affect how we approach phenomena related to language and ideology. Key Words: language policy, language education language teaching, language ideology Key Words: language policy, language education language teaching, language ideology LA IDEOLOGÍA LINGÜÍSTICA COMO MARCO CONCEPTUAL PARA ANALIZAR TEMAS RELACIONADOS A LA EDUCACIÓN Y LAS POLÍTICAS LINGÜÍSTICAS Resumen Este artículo aborda la manera en que las nociones de ideología o ideologías lingüísticas pueden ser usadas como herramientas analíticas para examinar temas relacionados a la educación y a las políticas lingüísticas. Primeramente, presenta una visión general de la ideología lingüística como campo de estudio. -

Becoming and Being a Highly Proficient Second Language Speaker of Finnish JYU DISSERTATIONS 309

JYU DISSERTATIONS 309 Katharina Ruuska At the Nexus of Language, Identity and Ideology Becoming and Being a Highly Proficient Second Language Speaker of Finnish JYU DISSERTATIONS 309 Katharina Ruuska At the Nexus of Language, Identity and Ideology Becoming and Being a Highly Proficient Second Language Speaker of Finnish Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston humanistis-yhteiskuntatieteellisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston vanhassa juhlasalissa S212 marraskuun 9. päivänä 2020 kello 17. Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences of the University of Jyväskylä, in building Seminarium, Old Festival Hall S212 on November 9, 2020 at 5 p.m. JYVÄSKYLÄ 2020 Editors Minna Suni Department of Language and Communication Studies, University of Jyväskylä Timo Hautala Open Science Centre, University of Jyväskylä Copyright © 2020, by University of Jyväskylä This is a printout of the original online publication. Permanent link to this publication: http://urn.fi/URN:978-951-39-8366-6 ISBN 978-951-39-8366-6 (PDF) URN:ISBN:978-951-39-8366-6 ISSN 2489-9003 Jyväskylä University Printing House, Jyväskylä 2020 ABSTRACT Ruuska, Katharina At the nexus of language, identity and ideology: Becoming and being a highly proficient second language speaker of Finnish Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä, 2020, 292 p. (JYU Dissertations ISSN 2489-9003; 309) ISBN 978-951-39-8366-6 (PDF) This multiple case study focuses on second language speakers of Finnish and their lived experience of everyday language use in Finland. The participants are late multilinguals who moved to Finland and learned Finnish as adults, and have reached a very advanced second language competence in Finnish. -

Arizona Tewa Kwa Speech As a Mantfestation of Linguistic Ideologyi

Pragmatics2:3.297 -309 InternationalPragmatics Association ARIZONA TEWA KWA SPEECH AS A MANTFESTATIONOF LINGUISTIC IDEOLOGYI Paul V. Kroskriw 1.Introduction "Whathave you learned about the ceremonies?" Back in the Summer of.7973,when I firstbegan research on Arizona Tewa, I was often asked such questionsby a variety of villagers.I found this strange,even disconcerting,since the questionspersisted after I explainedmy researchinterest as residing in the language "itself', or in "just the language,not the culture".My academicadvisors and a scholarlytradition encouraged meto attributethis responseto a combination of secrecyand suspicionregarding such culturallysensitive topics as ceremonial language.Yet despite my careful attempts to disclaimany researchinterest in kiva speech (te'e hi:li) and to carefully distinguish betweenit and the more mundane speech of everyday Arizona Tewa life, I still experiencedthese periodic questionings.Did thesequestions betray a native confusion of thelanguage of the kiva with that of the home and plaza? Was there a connection betweenthese forms of discoursethat was apparent to most Tewa villagersyet hidden fromme? In the past few years, after almost two decadesof undertaking various studiesof fuizonaTewa grammar, sociolinguistic variation, languagecontact, traditional nanatives,code-switching, and chanted announcements,an underlying pattern of languageuse has gradually emerged which, via the documentary method of interpretationhas allowed me to attribute a new meaning to these early intenogations.2The disparatelinguistic and discoursepractices, I contend, display a commonpattern of influencefrom te'e hi:li "kiva speech".The more explicit rules for languageuse in ritual performance provide local models for the generation and anluationof more mundanespeech forms and verbal practices. I Acknowledgements.I would like to thank Kathryn Woolard for her commentson an earlier rcnionof thisarticle which was presentedas part of the 1991American Anthropological Association rymposium,"language ldeologies: Practice and Theory'. -

Language Communities in the Village of Tewa

Language & Communication 38 (2014) 8–17 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Language & Communication journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/langcom Borders traversed, boundaries erected: Creating discursive identities and language communities in the Village of Tewa Paul V. Kroskrity* University of California, Los Angeles, Department of Anthropology, 341 Haines Hall-Box 951553, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1553, United States abstract Keywords: Today the Village of Tewa, First Mesa of the Hopi Reservation in Northern Arizona expe- Language Endangerment riences unprecedented linguistic diversity and change due to language shift to English. Linguistic Revitalization Despite a wide range of speaker fluency, the now emblematic Tewa language that their Languages as Emblems of Identity ancestors transported from the Rio Grande Valley almost 325 years ago, is widely valorized Language Ideologies within the community. However Language factions have emerged andtheir debates and Speech/Language Community Tewa contestations focus on legitimate language learning and the proper maintenance of their emblematic language. Boundary creation and crossing are featuresof discourses that rationalize possible forms of language revitalization and construct communities across temporal barriers. The theoretical implications of these discourseson both local and theoretical notions of language/speech community are explored. Ó 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction As in many communities faced with language endangerment, discourses of language and identity have been multiplied and magnified by contemporary transformations in the Village of Tewa. But this is a community wherein language and group identity have an especially long and rich history of linkage in actual practice and in indigenous metalinguistic commentary. Today the Arizona Tewas number around seven hundred individuals who reside on and near the Village of Tewa on First Mesa of the Hopi Reservation in NE Arizona. -

Telepoem Booth® Santa Fe

Telepoem Booth® Santa Fe by © Elizabeth Hellstern, 2019 funded through the City of Santa Fe Arts Commission This Telepoem Booth® is fully ADA Compliant The directory is printed in 18 pt. font. Feel free to adjust the phone volume on the volume control button. The full text of poems is available in this directory and online at telepoembooth.com/directories. Online PDF Telepoem Booth® directories compatible with vision-impaired translation devices are also available at telepoembooth.com/directories. Instructions: This phone is NOT WIRED for making outside calls. Emergency calls are not possible on this telephone. This phone provides free access to poetry recordings. 1. Locate a Telepoem number in the Telepoem Book. 2. Pick up the hand-set. 3. Dial ENTIRE TELEPOEM NUMBER (including area code.) 4. Repeat number dialing for entire Telepoem number. 5. Listen to the poem. (Adjust volume as necessary on volume control button at top left of phone.) 6. Hang up the phone when done. For more information, visit TelepoemBooth.com or facebook.com/ TelepoemBooth. For other directories of poems available to dial in this booth, visit telepoembooth.com/directories. © All poems used with permission. (Poems are only available to listen to in Telepoem Booths.) 4 Aylward-Bower Telepoem Booth® TELEPOEM BOOTH® POETS Aylward, Susan A susanaylward.wordpress.com The Black and the Light (1:30)...................................(505) 295-2522 B I Am From (2:22)........................................................(505) 295-4263 Seasons (:31).............................................................(505) -

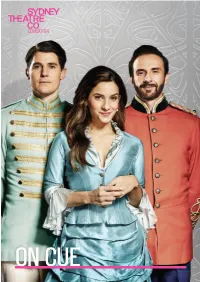

On Cue Table of Contents

ON CUE TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT ON CUE AND STC 2 CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS 3 CAST AND CREATIVES 4 FROM THE DIRECTOR 5 ABOUT THE PLAYWRIGHT 6 ABOUT THE PLAY 8 CONTEXT 9 SYNOPSIS 10 CHARACTER ANALYSIS 12 THEMES AND IDEAS 16 THE ELEMENTS OF DRAMA 20 STYLE 22 DESIGN 23 BIBLIOGRAPHY 24 Compiled by Hannah Brown. The activities and resources contained © Copyright protects this Education in this document are designed for Resource. educators as the starting point for Except for purposes permitted by the developing more comprehensive lessons Copyright Act, reproduction by whatever for this production. Hannah Brown means in prohibited. However, limited is the Education Projects Officers for photocopying for classroom use only is the Sydney Theatre Company. You can permitted by educational institutions. contact Hannah on [email protected] 1 ABOUT ON CUE AND STC ABOUT ON CUE STC Ed has a suite of resources located on our website to enrich and strengthen teaching and learning surrounding the plays in the STC season. Each show will be accompanied by an On Cue e-publication which will feature all the essential information for teachers and students, such as curriculum links, information about the playwright, synopsis, character analysis, thematic analysis and suggested learning experiences. For more in-depth digital resources surrounding the ELEMENTS OF DRAMA, DRAMATIC FORMS, STYLES, CONVENTIONS and TECHNIQUES, visit the STC Ed page on our website. SUCH RESOURCES INCLUDE: • videos • design sketchbooks • worksheets • posters ABOUT SYDNEY THEATRE COMPANY In 1980, STC’s first Artistic Director Richard Wherrett defined areas; and reaches beyond NSW with touring productions STC’s mission as to provide “first class theatrical entertainment throughout Australia. -

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general -

Language Ideologies, Multilingualism, and Social Media

2 Language Ideologies, Multilingualism, and Social Media The foundation of this book is the intersection of three areas of socio- linguistic research: language ideologies and language policy, language use in social media, and multilingual language use in interaction. Though these often tend to be regarded as largely separate and unre- lated fields of inquiry, they need to be woven together in order to form asufficiently robust theoretical framework within which to interpret the analysis in Chapters 3, 4,and5. In this chapter I will attempt to do just that by outlining the relevant research within each subfield, by pointing out the places where these bodies of research intersect, and by explaining the implications these linkages have for the analysis in this book. This chapter focuses first on the relationship between ideology and language, including a discussion of common ideologies regarding the position and status of English within Europe and the rest of the world, the ideology of nationalism and the role of the state, and the concept of ideology within a theory of globalization. I then move on to talk about language use in social media discourse, both in terms of the linguistic and interactional features that are typical of social media language and in © The Author(s) 2017 23 J. Dailey-O’Cain, Trans-National English in Social Media Communities, Language and Globalization, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-50615-3_2 24 2 Language Ideologies, Multilingualism, and Social Media terms of the provenance of different languages on the global internet. Finally, I end with a discussion of multilingual language use in interac- tion both in conventional spoken discourse and in social media, before coming back around again to the specific research questions I alluded to in Chapter 1. -

1 Vivian Cook and Benedetta Bassetti Over the Past Ten Years, Literacy In

1 CHAPTER 1: AN INTRODUCTION TO RESEARCHING SECOND LANGUAGE WRITING SYSTEMS Vivian Cook and Benedetta Bassetti Over the past ten years, literacy in the second language has emerged as a significant topic of inquiry in research into language processes and educational policy. This book provides an overview of the emerging field of Second Language Writing Systems (L2WS) research, written by researchers with a wide range of interests, languages and backgrounds, who give a varied picture of how second language reading and writing relates to characteristics of writing systems (WSs), and who address fundamental questions about the relationships between bilingualism, biliteracy and writing systems. It brings together different disciplines with their own theoretical and methodological insights – cognitive, linguistic, educational and social factors of reading – and it contains both research reports and theoretical papers. It will interest a variety of readers in different areas of psychology, education, linguistics and second language acquisition research. 1. What this book is about Vast numbers of people all over the world are using or learning a second language writing system. According to the British Council (1999), a billion people are learning English as a Second Language, and perhaps as many are using it for science, business and travel. Yet English is only one of the second languages in wide-spread use, although undoubtedly the largest. For many of these people – whether students, scientists or computer users browsing the internet – the ability to read and write the second language is the most important skill. The learning of a L2 writing system is in a sense distinct from learning the language and is by no means an easy task in itself, say for Chinese people learning to read and write English, or for the reverse case of English people learning to read and write Chinese.