Levelling the Lake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laurentide Ice-Flow Patterns: a Historical Review, and Implications of the Dispersal of Belcher Islands Erratics"

Article "Laurentide Ice-Flow Patterns: A Historical Review, and Implications of the Dispersal of Belcher Islands Erratics" Victor K. Prest Géographie physique et Quaternaire, vol. 44, n° 2, 1990, p. 113-136. Pour citer cet article, utiliser l'information suivante : URI: http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/032812ar DOI: 10.7202/032812ar Note : les règles d'écriture des références bibliographiques peuvent varier selon les différents domaines du savoir. Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d'auteur. L'utilisation des services d'Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d'utilisation que vous pouvez consulter à l'URI https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l'Université de Montréal, l'Université Laval et l'Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. Érudit offre des services d'édition numérique de documents scientifiques depuis 1998. Pour communiquer avec les responsables d'Érudit : [email protected] Document téléchargé le 12 février 2017 05:36 Géographie physique et Quaternaire, 1990, vol. 44, n°2, p. 113-136, 29 fig., 1 tabl LAURENTIDE ICE-FLOW PATTERNS A HISTORIAL REVIEW, AND IMPLICATIONS OF THE DISPERSAL OF BELCHER ISLAND ERRATICS Victor K. PREST, Geological Survey of Canada, 601 Booth Street, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0E8. ABSTRACT This paper deals with the evo Archean upland. Similar erratics are common en se fondant sur la croissance glaciaire vers lution of ideas concerning the configuration of in northern Manitoba in the zone of confluence l'ouest à partir du Québec-Labrador. -

An Overview of World-Class Gold Districts in Canada's Newest

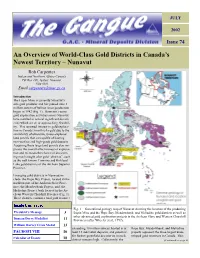

JULY 2002 Issue 74 An Overview of World-Class Gold Districts in Canada’s Newest Territory – Nunavut Rob Carpenter Indian and Northern Affairs Canada PO Box 100, Iqaluit, Nunavut, X0A 0H0 Email [email protected] Introduction The Lupin Mine is currently Nunavut’s sole gold producer and has poured over 3 million ounces of bullion since production began in 1982 (Fig. 1). However, recent gold exploration activities across Nunavut have resulted in several significant discov- eries which are at, or approaching, feasibil- ity. This renewed interest in gold explora- tion in Canada’s north is largely due to the availability of extensive, under-explored land parcels that are capable of hosting near-surface and high-grade gold deposits. Acquiring these large land parcels also im- proves the overall effectiveness of explora- tion and increases the chance of discover- ing much sought after gold “districts”, such as the well known Timmins and Kirkland Lake gold districts of the Archean Superior Province. Emerging gold districts in Nunavut in- clude: the Hope Bay Project, located in the northern part of the Archean Slave Prov- ince; the Meadowbank Project, and; the Meliadine Project, both located in the Ar- chean Western Churchill Province (Fig. 1). These districts contain a total gold resource ,QVLGH WKLV LVVXH Fig. 1 – Generalized geology map of Nunavut showing the location of the producing President’s Message 3 Lupin Mine and the Hope Bay, Meadowbank, and Meliadine gold districts as well as other advanced gold exploration projects in the Archean Slave and Western Churchill Duncan Derry Medallist 11 Provinces (after Wheeler et al., 1997). -

The Red River Resistance 1869–1870: the Machiavellian Moment

UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA Ph.D. THESIS DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA THE RED RIVER RESISTANCE OF 1869-1870: THE MACHIAVELLIAN MOMENT OF THE THE MÉTIS OF MANITOBA DARREN O'TOOLE Summary In October 1869, the fledgling Canadian federation was preparing for the transfer of Rupert’s Land and the Northwestern Territory when the Métis set up a Provisional Government in order to resist what they saw as a unilateral annexation of their homeland. Although there were multiple references made to ‘republicanism’ during the Resistance, no scholar has ever explored whether republican conventions were actually present in political discourse in the District of Assiniboia prior to the Resistance and whether they were effectively activated during the Resistance. Working from the Cambridge School approach of discourse analysis, this thesis first identifies the conventions of democratic rhetorical republicanism, which includes positive and negative liberty, the rule of law, the mixed and balanced constitution and citizenship, which in turn involves virtue, the militia and real property. It then looks at the gradual introduction in Assiniboia of republican discourse from multiple sources, including the United States, Lower Canada, Upper Canada, Ireland, France and Great Britain and its circulation throughout several practical political struggles during the period from 1835 to 1869. In doing so, it shows that certain ‘organic intellectuals’ acted as ‘transmission belts’ of republican conventions and that institutional structures were a factor that rendered the activation of such conventions almost inevitable. By the time the Resistance took place in 1869, a more or less fully developed republican paradigm formed part of the linguistic matrix and was available to political actors in Assiniboia. -

PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENTS 9.—Provinces and Territories Of

PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENTS 83 9.—Provinces and Territories of Canada, with present Areas, Dates of Admission to Confederation and Legislative Process by which this was effected. Present Area (square miles). Province, Date of Territory Admission Legislative Process. or District. or Creation. Land. Water. Total. Ontario July 1, 1867[Ac t of Imperial Parliament—The] 357,962 49,300 407,2621 Quebec " 1, 1867J British North America Act, 18671 571,004 23,430 594,4342 Nova Scotia " 1, 1867 (30-31 Vict., c. 3), and Imperial! 20,743 685 21,428 New Brunswick.. " 1, 1867[ Order in Council of May 22,1867. J 27,710 275 27,985 Manitoba " 15, 1870Manitob a Act, 1870 (33 Vict., c. 3) and Imperial Order in Council, June 23, 1870 224,777 27,055 251,8323 British Columbia. " 20, 1871Imperia l Order in Council, May 16,1871 349,970 5,885 355,855 P.E. Island " 1, 1873Imperia l Order in Council, June 26,1873 2,184 2,184 Saskatchewan Sept. 1, 1905Saskatchewa n Act, 1905 (4-5 Edw. VII, c. 42) 237,975 13,725 251,700* Alberta. " 1, 1905Albert a Act, 1905 (4-5 Edw. VII, c. 3). 248,80J 6,485 255,285* Yukon.. June 13, 1898Yuko n Territory Act, 1898 (61 Vict., c.6) 205,346 1,730 207,076 Mackenzie. Jan. 1, 1920 493,225 34,265 527,490 s Keewatin.. " 1, 1920-Orde r in Council, Mar. 16,1918. 218,460 9,700 228,160s Franklin... " 1, 1920 546,532 7,500 554,0325 Total. 3,504,688 180,035 3,684,733 1 The area of Ontario was extended by the Canada (Ontario Boundary) Act, 1889, and the Ontario Boundaries Extension Act, 1912 (2 Geo. -

Medicine in Manitoba

Medicine in Manitoba THE STORY OF ITS BEGINNINGS /u; ROSS MITCHELL, M.D. THE UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY LIBRARY FR OM THE ESTATE OF VR. E.P. SCARLETT Medic1'ne in M"nito/J" • THE STORY OF ITS BEGINNINGS By ROSS MITCHELL, M. D. .· - ' TO MY WIFE Whose counsel, encouragement and patience have made this wor~ possible . .· A c.~nowledg ments THE LATE Dr. H. H. Chown, soon after coming to Winnipeg about 1880, began to collect material concerning the early doctors of Manitoba, and many years later read a communication on this subject before the Winnipeg Medical Society. This paper has never been published, but the typescript is preserved in the medical library of the University of Manitoba and this, together with his early notebook, were made avail able by him to the present writer, who gratefully acknowledges his indebtedness. The editors of "The Beaver": Mr. Robert Watson, Mr. Douglas Mackay and Mr. Clifford Wilson have procured informa tion from the archives of the Hudson's Bay Company in London. Dr. M. T. Macfarland, registrar of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Manitoba, kindly permitted perusal of the first Register of the College. Dr. J. L. Johnston, Provincial Librarian, has never failed to be helpful, has read the manuscript and made many valuable suggestions. Mr. William Douglas, an authority on the Selkirk Settlers and on Free' masonry has given precise information regarding Alexander Cuddie, John Schultz and on the numbers of Selkirk Settlers driven out from Red River. Sheriff Colin Inkster told of Dr. Turver. Personal communications have been received from many Red River pioneers such as Archbishop S. -

Arctic Fox Migrations in Manitoba

Arctic Fox Migrations in Manitoba ROBERT E. WRIGLEY and DAVID R. M. HATCH1 ABSTRACT. A review is provided of the long-range movements and migratory behaviour of the arctic fox in Manitoba. During the period 1919-75, peaks in population tended to occur at three-year intervals, the number of foxes trapped in any particular year varying between 24 and 8,400. Influxes of foxes into the boreal forest were found to follow decreases in the population of their lemming prey along the west coast of Hudson Bay. One fox was collected in 1974 in the aspen-oak transition zone of southern Manitoba, 840 km from Hudson Bay and almost 1000 km south of the barren-ground tundra, evidently after one of the farthest overland movements of the species ever recorded in North America. &UMfi. Les migrations du renard arctique au Manitoba. On prksente un compta rendu des mouvements B long terme et du comportement migrateur du renard arctique au Manitoba. Durant la p6riode de 1919-75, les maxima de peuplement tendaient fi revenir B des intervalles de trois ans, le nombre de renards pris au pihge dans une ann6e donn6e variant entre 24 et 8,400. On a constat6 que l'atiiux de renards dans la for& bor6ale suivait les diminutions de population chezleurs proies, les lemmings, en bordure de la côte oceidentale de la mer d'Hudson. En 1974, on a trouv6 un renard dans la zone de transition de trembles et de ch€nes, dans le sud du Manitoba, B 840 kilomhtres de la mer d'Hudson et fi presque 1000 kilomh- tres au sud des landes de la tundra. -

Provincial Plaques Across Ontario

An inventory of provincial plaques across Ontario Last updated: May 25, 2021 An inventory of provincial plaques across Ontario Title Plaque text Location County/District/ Latitude Longitude Municipality "Canada First" Movement, Canada First was the name and slogan of a patriotic movement that At the entrance to the Greater Toronto Area, City of 43.6493473 -79.3802768 The originated in Ottawa in 1868. By 1874, the group was based in Toronto and National Club, 303 Bay Toronto (District), City of had founded the National Club as its headquarters. Street, Toronto Toronto "Cariboo" Cameron 1820- Born in this township, John Angus "Cariboo" Cameron married Margaret On the grounds of his former Eastern Ontario, United 45.05601541 -74.56770762 1888 Sophia Groves in 1860. Accompanied by his wife and daughter, he went to home, Fairfield, which now Counties of Stormont, British Columbia in 1862 to prospect in the Cariboo gold fields. That year at houses Legionaries of Christ, Dundas and Glengarry, Williams Creek he struck a rich gold deposit. While there his wife died of County Road 2 and County Township of South Glengarry typhoid fever and, in order to fulfil her dying wish to be buried at home, he Road 27, west of transported her body in an alcohol-filled coffin some 8,600 miles by sea via Summerstown the Isthmus of Panama to Cornwall. She is buried in the nearby Salem Church cemetery. Cameron built this house, "Fairfield", in 1865, and in 1886 returned to the B.C. gold fields. He is buried near Barkerville, B.C. "Colored Corps" 1812-1815, Anxious to preserve their freedom and prove their loyalty to Britain, people of On Queenston Heights, near Niagara Falls and Region, 43.160132 -79.053059 The African descent living in Niagara offered to raise their own militia unit in 1812. -

"Lac Des Mille Lacs Indians, Live Exclusively By

"A War without Bombs": The Government's Role in Damming and Flooding of Lac des Mille Lacs First Nation By Howard Adler A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Canadian Studies Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario August 18, 2010 2010, Howard Adler Library and Archives Biblioth&que et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de Edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-71599-4 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-71599-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Nnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

The Boundaries of Canada

THE BOUNDARIES OF CANADA A. F. N. POOLE* Toronto 1. General Introduction . Throughout its history Canada has been concerned with both international and internal boundary problems, and the purpose of this article is to present the legal authorities by which they were settled. The international boundaries were finally determined early in this century, and this article does not cover such secondary problems as the utilization of international rivers,' particularly the Columbia,' St. Lawrence' and Niagara`' Rivers, the Air De- fence Identification Zones,' the use of the contiguous zone for fisheries conservation' and the status in international law of Hud- *A. F. N. Poole, M.A. (Oxon.), LL.B., Toronto . 1 See Robert A. MacKay, The International Joint Commission between the United States and Canada (1928), 22 Am. J. of Int. L. 292 ; Clyde Eagleton, The Use of the Waters of International Rivers (1955), 33 Can. Bar Rev. 1018 ; Robert Day Scott, The Canadian-American Boundary Waters Treaty : Why Article II? (1958), 36 Can. Bar Rev . 511 ; L. M . Bloomfield and G. F. Fitzgerald, Boundary Waters Problems of Canada and the United States (1958) ; William L. Griffin, The Use of the Waters of International Drainage Basins under Customary International Law (1959), 53 Am. J. of Int . L. 50 ; Jacob Austin, Canadian-United States Practice and Theory Respecting the International Law of International Rivers (1959), 37 Can. Bar Rev . 393 ; Ludwik A. Leclaff, United States River Treaties (1963), 31 Fordham L. Rev. 697 ; L.J. Bouchez, The Fixing of Boundaries in International Boundary Rivers (1963), 12 Int . & Comp . L.Q. 789. a See C. -

2.—Provincial Governments

74 CONSTITUTION AND GOVERNMENT is increased by four seats and now is composed of Parkdale, Toronto East, Toronto East Centre, Toronto-High Park, Toronto Northeast, Toronto Northwest, Toronto- Scarborough, Toronto South and Toronto West Centre. Manitoba.—Winnipeg Centre is replaced by Winnipeg North Centre and Winnipeg South Centre, while St. Boniface is created a separate constituency. Saskatchewan.—Six new seats are created—Long Lake, Melville, Melfort, Rosetown, Willowbunch and Yorkton. The riding of Saltcoats is ehminated. Alberta.—In the increase of four seats from Alberta, the ridings of Victoria and Strathcona are done away with and new seats for Acadia, Athabaska, Camrose, Peace River, Vegreville and Wetaskiwin are created. British Columbia.—A new seat is created in Vancouver, Centre, North and South ridings now replacing the former Vancouver Centre and Vancouver South. Yukon.—No change. 2.—Provincial Governments. Table 10 gives the names and areas, as in 1924, of the several provinces, terri tories and provisional districts of the Dominion, together with the dates of their creation or admission into the Confederation and the legislative process by which this was effected. » 10.—Provinces and Territories of Canada, with present Areas, Dates of Admission to Confederation and Legislative Process by which this was effected. Province, Date of Present Area (square miles). Territory Admission Legislative Process. or District. or Creation. Land. Water. Total. Ontario July 1, 1867 Act of Imperial Parliament— 365,880 41,382 407,2621 Quebec " 1, 1867 The British North America 690,865 15,969 706,8342 Nova Scotia 1, 1867 Act, 1867 (30-31 Vict.,c. 3), and 21,068 360 21,428 New Brunswick " 1, 1867 Imperial Order in Council of 27,911 74 27,985 May 22, 1867. -

Métis Nation 2020 – Manitoba

~1~ Métis Nation 2020 – Manitoba 150 A year to acknowledge and celebrate 150 years of the Métis and Louis Riel - the Founder of Manitoba, Leader of the Métis Nation, and Defender of Minority Rights ~2~ www.metisnation.ca ~3~ A SPECIAL MESSAGE FROM PRESIDENT DAVID CHARTRAND 2020 was an incredible year of challenges and celebration. The COVID-19 pandemic ushered in a new global era of social distancing and shutdowns. Many people lost their lives to this virus across the world and in our province and many more felt the nancial and mental effects. The pandemic was also an uninvited guest to our Manitoba 150 activities and stole many of our celebrations from us. But the Métis people have faced hardship before. We found innovative ways to remain connected to our loved ones and our communities, in spite of the pandemic. We also found new ways to mark the important milestone of Manitoba’s 150 – the anniversary of Manitoba’s entry into Canada’s Confederation. Manitoba’s Premier, Brian Pallister, tried to cut us out of the celebration. He did not involve the Métis Government when assembling the committee, nor did he request our input on the festivities that were planned. Of course, we did not allow that to pass. Rather, we had our own celebration that was open to all Manitobans, thanks to the support of the Government of Canada. It would be impossible to celebrate Manitoba 150 without recognizing the special relationship between the province and the Métis people. It was in 1870 that Louis Riel, Métis leader and President of the Provisional Government, along with his Cabinet and representatives from the Red River Settlement parishes, established the terms of negotiation for Manitoba’s entry into the Confederation of Canada. -

Kasmere Lake NTS

Manitoba Geological Survey B.G.C.M. Series Kasmere Lake, NTS 64N, 1:250 000 MARGINAL NOTES LEGEND The Kasmere Lake map area (NTS 64N) lies on the south and east flanks of the Hearne Province, part of the The Wollaston Domain and Seal River Domain share a common lithostratigraphy and metamorphic history. MUDJATIK DOMAIN SEAL RIVER DOMAIN Archean Rae-Hearne craton. The Snowbird Shear Zone divides the Rae-Hearne craton into the Rae Province Wollaston Group paragneiss unconformably overlies Archean granitoid rocks and possibly Archean volcanic Proterozoic Proterozoic to the west and the Hearne Province to the east (Hoffman, 1990). The Archean continental crust of the Hearne and sedimentary-derived gneiss. The Wollaston Domain is a northeast-trending fold belt with minor Hudsonian O O 0 102 O 100 0 0 0 Province is overlain by Paleoproterozoic cover rocks and, together with the cover rocks, has undergone varying plutonism, whereas the Seal River Domain exhibits an early, easterly trending, open fold set locally overprinted 30’ 0 30’ Hudsonian Hudsonian 350000 101 degrees of thermotectonism during the Paleoproterozoic Trans-Hudson orogeny (Cree Lake Ensialic Mobile by northeasterly structures. The Seal River Domain contains a greater volume of Hudsonian plutons. O 400000 Nunavut O Granite; Gf - pink granite, fluorite bearing; Gj - granite and 0 60 60 0 Granite, massive to foliated, aplite pegmatite; Gp - pink 66 granodiorite diatexite to biotite-metatexite garnet; Zone; Lewry et al., 1978; Lewry and Sibbald, 1980). Parts of the Hearne Province are considered to be H G G Gf W HW 50 porphyritic granite cratonic or semicratonic with respect to the Trans-Hudson Orogen, since they are little affected by Hudsonian The Wollaston Domain is defined by 1) the predominance of supracrustal-derived gneisses of the Wollaston Gw Manitoba Gw - granite and Hurwitz Group metagreywacke, Tk R G 000 thermotectonism.