Arctic Social Indicators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AMATII Proceedings

PROCEEDINGS: Arctic Transportation Infrastructure: Response Capacity and Sustainable Development 3-6 December 2012 | Reykjavik, Iceland Prepared for the Sustainable Development Working Group By Institute of the North, Anchorage, Alaska, USA 20 DECEMBER 2012 SARA FRENCH, WALTER AND DUNCAN GORDON FOUNDATION FRENCH, WALTER SARA ICELANDIC COAST GUARD INSTITUTE OF THE NORTH INSTITUTE OF THE NORTH SARA FRENCH, WALTER AND DUNCAN GORDON FOUNDATION Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................ 5 Acknowledgments .........................................................................6 Abbreviations and Acronyms ..........................................................7 Executive Summary .......................................................................8 Chapters—Workshop Proceedings................................................. 10 1. Current infrastructure and response 2. Current and future activity 3. Infrastructure and investment 4. Infrastructure and sustainable development 5. Conclusions: What’s next? Appendices ................................................................................ 21 A. Arctic vignettes—innovative best practices B. Case studies—showcasing Arctic infrastructure C. Workshop materials 1) Workshop agenda 2) Workshop participants 3) Project-related terminology 4) List of data points and definitions 5) List of Arctic marine and aviation infrastructure ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION INSTITUTE OF THE NORTH INSTITUTE OF THE NORTH -

The Regional Distribution of Zeolites in the Basalts of the Faroe Islands and the Significance of Zeolites As Palaeo- Temperature Indicators

The regional distribution of zeolites in the basalts of the Faroe Islands and the significance of zeolites as palaeo- temperature indicators Ole Jørgensen The first maps of the regional distribution of zeolites in the Palaeogene basalt plateau of the Faroe Islands are presented. The zeolite zones (thomsonite-chabazite, analcite, mesolite, stilbite-heulandite, laumontite) continue below sea level and reach a depth of 2200 m in the Lopra-1/1A well. Below this level, a high temperature zone occurs characterised by prehnite and pumpellyite. The stilbite-heulan- dite zone is the dominant mineral zone on the northern island, Vágar, the analcite and mesolite zones are the dominant ones on the southern islands of Sandoy and Suðuroy and the thomsonite-chabazite zone is dominant on the two northeastern islands of Viðoy and Borðoy. It is estimated that zeolitisa- tion of the basalts took place at temperatures between about 40°C and 230°C. Palaeogeothermal gradients are estimated to have been 66 ± 9°C/km in the lower basalt formation of the Lopra area of Suðuroy, the southernmost island, 63 ± 8°C/km in the middle basalt formation on the northernmost island of Vágar and 56 ± 7°C/km in the upper basalt formation on the central island of Sandoy. A linear extrapolation of the gradient from the Lopra area places the palaeosurface of the basalt plateau near to the top of the lower basalt formation. On Vágar, the palaeosurface was somewhere between 1700 m and 2020 m above the lower formation while the palaeosurface on Sandoy was between 1550 m and 1924 m above the base of the upper formation. -

Kujalleq Nutaaq ERHVERVSUDVIKLINGS FORSLAG for Kommune Kujalleq

Kujalleq Nutaaq ERHVERVSUDVIKLINGS FORSLAG for Kommune Kujalleq Version 1.0 - 2020 Innovation South Greenland A/S, Torvevej 34, Postboks 313, 3920 Qaqortoq, Greenland Oqarasuaat +299 537777, e-mail: [email protected] Forord Innovation South Greenland arbejder målrettet for at få udviklingen i gang i hele Sydgrønland. Dette dokument afspejler anbefalingerne til Kommunalbestyrelsen. 1. Ser man på infrastrukturen er det gennem en årrække blevet svært at rejse rundt i Kommunen. 2. Det er en udfordring at få vareforsyninger, dyrt og svært at sende varer fra sydgrønland og svært at holde møder osv. Af disse og flere andre årsager er udviklingen gået nærmest i stå. 3. Resultatet har været at der er sket en gradvis en fraflytning. Desuden har personer med højere kompetencer fået gode jobs andre steder. Det er ganske enkelt blevet svært at skabe et livsgrundlag på et personligt plan, for familier og for erhvervslivet. Derfor har man etableret Innovation South Greenland A/S for at skabe vækst, udvikling og rådgivning af iværksættere. En konkret opgave som er blevet givet Innovation South Greenland A/S er at finde en løsning for Narsarsuaq i et nyt scenarie. Det vigtige er imidlertid at se på hele Sydgrønland som en sammenhængende region. Den første forudsætning er at skabe håb og troværdighed. Dernæst at man får en tidssvarende infrastruktur på plads. Ydermere skal der opdyrkes en iværksætterkultur som understøttes af igangsætning af konkrete projekter. Sidst og ikke mindst skal der tiltrækkes investeringer udefra og indgås bilaterale aftaler som kan styrke regionen. Erhvervsudviklingen skal baseres på et tæt samarbejde med Erhvervslivet, Kommunen, Selvstyret og Uddannelsesinstitutionerne i kommunen. -

NN 08.27.2015 16 Pagesdiana.Qxp Layout 1

Photo by Nikolai Ivanoff FALL STORM— The first fall storm began hitting the shores of Norton Sound and the Seward Peninsula on Monday. A gold mining jackup rig weathered the storm at West Beach. C VOLUME CXV NO. 34 August 27, 2015 Council: Imported pot in, utility rates up By Sandra L. Medearis on the issues yielded mixed results. About 15 people attended Nome When the marijuana measure Common Council’s regular meeting came up, several persons, notably on Monday evening, an unusually Tim Smith and Jim Stimpfle, impor- high number to participate in the tuned the Council to delete a clause panel’s open meetings. limiting marijuana for sale within The attendance was due to public city limits to “Nome grown.” The hearings and final votes on some ap- Council went for it, striking down parently red button topics on the that section of the ordinance, voting agenda: Marijuana regulations, a 4-1 on a motion by Jerald Brown. noise ordinance, firearms law and a Matt Culley cast the lone ‘no’ vote. utility rate hike. Also, several relatives came along Pot sales to back an appeal by Nancy Banning import of marijuana for Mendenhall for the Council to ap- sales within the city limits would en- prove a variance to building regula- courage a large marijuana and mari- tions previously denied by Nome juana products store to open outside Planning Commission. Soapboxing before the Council continued on page 4 Savoonga man found guilty of rape, assault By Diana Haecker hol and marijuana to minors. A party held at Calvin Akeya’s According to court testimony dur- home in Savoonga in March 2014 ing a jury trial held from August 18 went terribly wrong for two women until August 20 in Nome, Akeya – one adult and a minor - whose lives served homebrew alcohol to several were changed that night. -

Laurentide Ice-Flow Patterns: a Historical Review, and Implications of the Dispersal of Belcher Islands Erratics"

Article "Laurentide Ice-Flow Patterns: A Historical Review, and Implications of the Dispersal of Belcher Islands Erratics" Victor K. Prest Géographie physique et Quaternaire, vol. 44, n° 2, 1990, p. 113-136. Pour citer cet article, utiliser l'information suivante : URI: http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/032812ar DOI: 10.7202/032812ar Note : les règles d'écriture des références bibliographiques peuvent varier selon les différents domaines du savoir. Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d'auteur. L'utilisation des services d'Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d'utilisation que vous pouvez consulter à l'URI https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l'Université de Montréal, l'Université Laval et l'Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. Érudit offre des services d'édition numérique de documents scientifiques depuis 1998. Pour communiquer avec les responsables d'Érudit : [email protected] Document téléchargé le 12 février 2017 05:36 Géographie physique et Quaternaire, 1990, vol. 44, n°2, p. 113-136, 29 fig., 1 tabl LAURENTIDE ICE-FLOW PATTERNS A HISTORIAL REVIEW, AND IMPLICATIONS OF THE DISPERSAL OF BELCHER ISLAND ERRATICS Victor K. PREST, Geological Survey of Canada, 601 Booth Street, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0E8. ABSTRACT This paper deals with the evo Archean upland. Similar erratics are common en se fondant sur la croissance glaciaire vers lution of ideas concerning the configuration of in northern Manitoba in the zone of confluence l'ouest à partir du Québec-Labrador. -

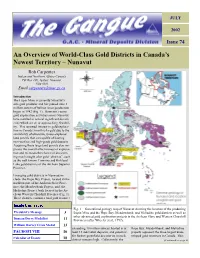

An Overview of World-Class Gold Districts in Canada's Newest

JULY 2002 Issue 74 An Overview of World-Class Gold Districts in Canada’s Newest Territory – Nunavut Rob Carpenter Indian and Northern Affairs Canada PO Box 100, Iqaluit, Nunavut, X0A 0H0 Email [email protected] Introduction The Lupin Mine is currently Nunavut’s sole gold producer and has poured over 3 million ounces of bullion since production began in 1982 (Fig. 1). However, recent gold exploration activities across Nunavut have resulted in several significant discov- eries which are at, or approaching, feasibil- ity. This renewed interest in gold explora- tion in Canada’s north is largely due to the availability of extensive, under-explored land parcels that are capable of hosting near-surface and high-grade gold deposits. Acquiring these large land parcels also im- proves the overall effectiveness of explora- tion and increases the chance of discover- ing much sought after gold “districts”, such as the well known Timmins and Kirkland Lake gold districts of the Archean Superior Province. Emerging gold districts in Nunavut in- clude: the Hope Bay Project, located in the northern part of the Archean Slave Prov- ince; the Meadowbank Project, and; the Meliadine Project, both located in the Ar- chean Western Churchill Province (Fig. 1). These districts contain a total gold resource ,QVLGH WKLV LVVXH Fig. 1 – Generalized geology map of Nunavut showing the location of the producing President’s Message 3 Lupin Mine and the Hope Bay, Meadowbank, and Meliadine gold districts as well as other advanced gold exploration projects in the Archean Slave and Western Churchill Duncan Derry Medallist 11 Provinces (after Wheeler et al., 1997). -

Panel 2A Abstracts

Panel 2A: Greenland-Denmark relations in history: Insights from the ERC Arctic Cultures project Format: Paper panel in English Conveners: Dr Peter Martin & Richard Powell Panel 2A abstract: This panel will present findings from the European Research Council funded project, ‘Arctic Cultures’, 2017-22, that relate to the conference theme on Greenland-Denmark relations. The ARCTIC CULT project investigates the imaginative construction of the Arctic that emerged from the exploration of the region by Europeans and North Americans and their contacts with indigenous peoples from the middle of the sixteenth century. During the exploration and colonisation of the Arctic, particular texts, cartographic representations and objects were collected and returned to sites like Copenhagen, Berlin, Philadelphia and New York. The construction of the Arctic thereby became entwined with the growth of colonial museum cultures and, indeed, western modernity. The panel will present aspects of research from the project that focus upon relations between Greenland and Denmark, as well as other imperial states such as Britain and Germany. Studying transnational histories of knowledge co-production, papers will reflect on the formations of cartographic, ethnographic and geographic knowledges within the Danish-Greenlandic colonial context. The panel will also consider the extent to which these processes of knowledge formation continue to have important consequences for contemporary relations between Greenland and Denmark. Speaker 1: Dr Richard Powell Title: Introduction to the Panel – ERC Arctic Cultures Project Abstract: A brief introduction to the ERC Arctic Cultures project and the context for the panel papers and discussion. Speaker 2: Dr Peter Martin Title: Anthropogeography in the Arctic: H.P. -

A. F. Kashevarov, the Russian -American Company and Alaska

A. F. KASHEVAROV, THE RUSSIAN-AMERICAN COMPANY, AND ALASKA CONSERVATION Ryan Tucker Jones Idaho State University, 935 W. Clark St., Pocatello, ID 83204; [email protected] ABSTRACT As Russia debated selling Alaska in the 1860s, A. F. Kashevarov, an Alaska Creole, published his thoughts about reforming the Russian-American Company (RAC). In several articles for the Russian naval journal Morskoi Sbornik, he described the RAC’s hunting policies and conservation measures. Kashevarov’s articles represent some of the few sources providing information on Russian-era tradi- tional ecological knowledge (TEK), even if his depth of knowledge concerning Aleut (Unangan) and Alutiiq environmental practices and conceptions is uncertain. Despite company claims of conserva- tion successes, in Kashevarov’s view the RAC had misunderstood the Alaska environment and mis- managed its fur resources. Claiming that marine mammals behaved unpredictably and were entwined in a complex ecology, Kashevarov insisted that company attempts to create zapusks (closed seasons) did not work. Instead, he proposed that only Alaska Natives understood the animals well enough to manage them and thus should be ceded control over Alaska’s environment. Though these radical claims were met with company derision, Kashevarov’s pleas for ecological sophistication and ecologi- cal justice provide some glimpse into the desires of Alaska Natives shortly before the colony’s demise. INTRODUCTION In the 1860s, as the Russian empire debated selling Alaska see Dmytryshyn et al. 1989:518–524), shed valuable light to the United States, some new, unexpected voices arose to on Alaska’s environmental history, the RAC’s conserva- challenge Russian-American Company (RAC) adminis- tion policies, and the history of Alaska Natives and hint trators and imperial officials and put forth their own plans at alternate paths not taken but that still seemed possi- for the colony. -

Fast Solar Wind Monitor (BMSW): Description and First Results

Space Sci Rev (2013) 175:165–182 DOI 10.1007/s11214-013-9979-4 Fast Solar Wind Monitor (BMSW): Description and First Results Jana Šafránková · Zdenekˇ Nemeˇ cekˇ · Lubomír Prechˇ · Georgy Zastenker · Ivo Cermákˇ · Lev Chesalin · Arnošt Komárek · Jakub Vaverka · Martin Beránek · Jiríˇ Pavl˚u · Elena Gavrilova · Boris Karimov · Arkadii Leibov Received: 4 September 2012 / Accepted: 19 March 2013 / Published online: 6 April 2013 © Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2013 Abstract Monitoring of solar wind parameters is a key problem of the Space Weather pro- gram. The paper presents a description of a novel fast solar wind monitor (Bright Monitor of the Solar Wind, BMSW) and the first results of its measurements of plasma moments with a time resolution ranging from seconds to 31 ms. The method of the fast monitoring is based on simultaneous measurements of the total ion flux and ion integral energy spectrum by six nearly identical Faraday cups (FCs). Three of them are dedicated to determination of the ion flow direction, whereas other three equipped with control grids supplied by a re- tarding potential are used for a determination of the density, temperature, and speed of the plasma flow. The paper introduces not only the measuring methods, the FCs design, and modes of operation, but brings the examples of time series of measurements and their com- parison with the observations of other spacecraft as well as the first results of an analysis of frequency spectra of solar wind fluctuations within the ion kinetic scale, examples of rapid measurements at the ramp of an interplanetary shock and investigations of fast variations of alpha particle content. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Aboriginal Organizations and with Manitoba Education, Citizenship and Youth

ABORIGINAL ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People 2011/2013 ABORIGINAL ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Métis People 2011 / 2013 ________________________________________________________________ Compiled and edited by Aboriginal Education Directorate and Aboriginal Friendship Committee Fort Garry United Church Winnipeg, Manitoba Printed by Aboriginal Education Directorate Manitoba Education, Manitoba Advanced Education and Literacy and Aboriginal Affairs Secretariat Manitoba Aboriginal and Northern Affairs INTRODUCTION The directory of Aboriginal organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to assist people to locate the appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Aboriginal organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown considerably since its initial edition, which had 16 pages compared to the 100 pages of the present edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Aboriginal cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present in this directory an accurate and up-to-date listing. Fax numbers, Email addresses and Websites have been included whenever available. Inevitably, errors and omissions will have occurred in the revising and updating of this Directory, and the committee would greatly appreciate receiving information about such oversights, as well as changes and new information to be included in a future revision. Please call, fax or write to the Aboriginal Friendship Committee, Fort Garry United Church, using the information on the next page. -

Annexe: Summary of Soviet and Russian Space Science Missions

Contents Introduction by the authors ..................................... ix Acknowledgments ............................................ xi Glossary .................................................. xiii Terminological and translation notes ..............................xv Reference notes .............................................xvii List of tables ............................................... xix List of illustrations ......................................... xxiii List of figures .............................................xxvii 1 Early space science ........................................... 1 Space science by balloon....................................... 3 Scientific flights into the atmosphere: the Akademik series..............14 Scientific test flights with animals ................................20 The idea of a scientific Earth satellite .............................23 Scientific objectives of the first Earth satellites . ....................25 Key people .................................................25 Instead, Prosteishy Sputnik .....................................27 PS2......................................................29 Object D: the first large scientific satellite in orbit....................33 Early space science: what was learned? ............................37 References .................................................39 2 Deepening our understanding ....................................43 Following Sputnik: the MS series ................................43 Cosmos 5 and Starfish: introducing Yuri Galperin