Acre Lucrecia Zappi Extract (Chapters 1,2 and 6) Translated by Lisa Shaw

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jim Crow at the Beach: an Oral and Archival History of the Segregated Past at Homestead Bayfront Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Biscayne National Park Jim Crow at the Beach: An Oral and Archival History of the Segregated Past at Homestead Bayfront Park. ON THE COVER Biscayne National Park’s Visitor Center harbor, former site of the “Black Beach” at the once-segregated Homestead Bayfront Park. Photo by Biscayne National Park Jim Crow at the Beach: An Oral and Archival History of the Segregated Past at Homestead Bayfront Park. BISC Acc. 413. Iyshia Lowman, University of South Florida National Park Service Biscayne National Park 9700 SW 328th St. Homestead, FL 33033 December, 2012 U.S. Department of the InteriorNational Park Service Biscayne National Park Homestead, FL Contents Figures............................................................................................................................................ iii Acknowledgments.......................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 A Period in Time ............................................................................................................................. 1 The Long Road to Segregation ....................................................................................................... 4 At the Swimming Hole .................................................................................................................. -

I Bullets Slew Attica Hostages, Medical Examiner Reports

The Weather assenvbly in a numbe'r-of timely Clei^ng and cooler tonkpit The VFW Auxiliary will meet St. Mary’s Episcopal Church choruses. ' _ ’ . with low In low 60e. Wedneedity tomorrow at 7:80 p.m.'. at the has scheduled choir rehearsals Bandsman Wallace Shauger, ■unny and pteneant;' high In up Poet Hoihe. Members are re to begin tomorrow. The Junior who was program chairman, per 70a. Thureday’e outlook,. Manohefter WA/TB16 will go on minded to bring items for the choir will meet at 6:80 p.m. and becoming cloudy agnln. a mystery ,rlde tomorrow. spoke on the topic, “ Are You in teacup auction which will be af the Senior choir at 7:46 p.m. at ■ The muslcsof bag pipes filled Focus?" Mancheuter^A City of Village Charm Weighing in at the Italian-Amer- ter the 'buelnesa niee'ting. meet in October. the church. This will be the last- loan CSUb will be from 6 to 7 the Youth Cenlar of the Salva Following the benedlcation by rehearsal with Steven Lowry. tion Army yesttelday ns Roger Capt. Lawrence Beadle, Ritchie p.m.- Mrs. James Desautels will The executive board of VOL. LXXXX, NO. 293 (EIGHTEEN PAGES) (Olaaetfled Adverttalng on Page 15) PRICE FIFTEEN CENT! Manchester Registered Ifuines New members are welcome. Ritchie played a ^ ^ ed ley of again played the bag pipes. MANCHESTER, CONN;, 1*UESDAY, SEPTEMBER 14, 1971 he inoharge of the program. Church Women United will Association will meet Wednes tunes for the opening egerclsee The program was arranged meet tomorrow at 13 ;80 p.m. -

PDF of This Issue

MIT’s The Weather Oldest and Largest Today: Chance of rain, 50°F (10°C) Tonight: Mostly clear, 37°F (3°C) Newspaper Tomorrow: Partly sunny, 52°F (11°C) Details, Page 2 Volume 124, Number 18 Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 Friday, April 9, 2004 Unlicensed Viewings Singh Elected as GSC President, Make MIT Pay $14K, Treasurer Position Still Unfilled By Kathy Dobson and Lucy Wong G treasurer. The from the academic departments and STAFF REPORTER election for treasurer was postponed programs, representatives from the Seek Blanket License The Graduate Student Council until either a special session or the dormitories, off-campus representa- held elections for its 2004-2005 next general council meeting, to be tives, the chairs of the GSC commit- By Marissa Vogt sites and mailed them to MIT,” officials on Wednesday. Barun held on May 5. tees, the ASA President, and some NEWS EDITOR Robinson said. Singh G was elected president, Hec- The candidates were elected by MIT recently paid $14,000 to a He said he did not know the tor H. Hernandez G vice president, current officers, representatives GSC, Page 16 copyright licensing company that name of the company that took the found evidence that several student screenshots, and would not say groups held publicized, unlicensed which student groups had advertised showings of copyrighted movies. the films without a license. As a result, MIT is exploring the The $14,000 that MIT paid was option of purchasing a blanket not so much a fine for not having a copyright license that would allow copyright license, but more of a student groups to legally show back payment for showing the movies, said Thomas E. -

Crystal Reports Activex Designer

Quiz List—Reading Practice Page 1 Printed Monday, January 30, 2012 1:44:57PM School: Firelands Elementary School Reading Practice Quizzes Quiz Word Number Lang. Title Author IL ATOS BL Points Count F/NF 46618 EN Cats! Brimner, Larry Dane LG 0.3 0.5 49 F 9318 EN Ice Is...Whee! Greene, Carol LG 0.3 0.5 59 F 31584 EN Big Brown Bear McPhail, David LG 0.4 0.5 99 F 9306 EN Bugs! McKissack, Patricia C. LG 0.4 0.5 69 F 86010 EN Cat Traps Coxe, Molly LG 0.4 0.5 95 F 84997 EN Colors and the Number 1 Sargent, Daina LG 0.4 0.5 81 F 9334 EN Please, Wind? Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 55 F 9336 EN Rain! Rain! Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 63 F 9338 EN Shine, Sun! Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 66 F 9353 EN Birthday Car, The Hillert, Margaret LG 0.5 0.5 171 F 64100 EN Daniel's Pet Ada, Alma Flor LG 0.5 0.5 77 F 9314 EN Hi, Clouds Greene, Carol LG 0.5 0.5 58 F 31858 EN Hop, Skip, Run Leonard, Marcia LG 0.5 0.5 110 F 26922 EN Hot Rod Harry Petrie, Catherine LG 0.5 0.5 63 F 69269 EN My Best Friend Hall, Kirsten LG 0.5 0.5 91 F 60939 EN Tiny Goes to the Library Meister, Cari LG 0.5 0.5 110 F 9349 EN Whisper Is Quiet, A Lunn, Carolyn LG 0.5 0.5 63 NF 26927 EN Bubble Trouble Hulme, Joy N. -

Kennedy Meeks

CELEBRITY SPOTLIGHTS POPPY MONTGOMERY THE STORY! BROOKE SHIELDS ELIZABETH BLAU LILY JAMES GEOFFREY ZAKARIAN Brandon Routh stars in “DC’s Legends of WHAT'S FOR Tomorrow,” premiering Thursday on The CW. DINNER Featuring: “Junk Food Flip” FEATURED STORIES EXCLUSIVE! “Billions” “Mercy Street” PROFILED “Angie Tribeca” ATHLETE MOVIES TO KENNEDY WATCH MEEKS And so much more! Connect to these shows within this magazine! FOLIO Courtesy of Gracenote January 17 - 23, 2016 What’s C HOT this Week! Click to jump to these contents featured sections! YOURTVLINK “BIllIONS” CELEBRITY Emmy winners Paul Giamatti and 4 POppY MONTGOMERY Damian Lewis square off. “Unforgettable” star’s history with the show is easy to remember 5 BROOKE SHIELDS “Flower Shop Mystery” star is looking to have some fun 6 ELIZABETH BLAU Blau has an eye for talent 8 LILY JAMES “Downton Abbey” alum “MERCY Street” moves on to “War & A love letter to valiant early Peace” nurses 9 GEOffREY ZAKARIAN Getting to know the Iron “ANGIE TRIBECa” Chef ‘Angie’ says silly things with a straight face 17 FOOD 7 “JUNK FOOD FLIP” Fewer calories, greater enjoyment THE STORY! SPORTS “DC’S LEGENDS OF 18-19 KENNEDY MEEKS TOMORROW” Kennedy Meeks and the ‘Legends’ versus evil North Carolina Tar Heels chase another title MOVIES IN EVERY ISSUE REALITY 20-21 Featuring: Theatrical 22-23 Featuring: Our top “PLANET PRIMETIME” Review, Our top DVD pick, 16 suggested programs to watch ‘Planet’ of pain and Coming Soon on DVD. this week! Page 2 YOUR TV LINK Courtesy of Gracenote January 17 - 23, 2016 Editor's choice STORY S ‘Legends’ band together to save humanity in new CW series BY GEORGE DICKIE It’s 2166 and immortal evil madman Vandal Savage is about to achieve his goal of the total annihilation of humanity. -

Congratulations to the 2018 Kirkus Prize Finalists from the Editor’S Desk

Featuring 239 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA Books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVI, NO. 20 | 15 OCTOBER 2018 REVIEWS Congratulations to the 2018 Kirkus Prize finalists from the editor’s desk: Chairman The 2018 Kirkus Prize Finalists HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY CLAIBORNE SMITH MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] Photo courtesy Michael Thad Carter courtesy Photo Congratulations to the writers, illustrators, and translators chosen as finalists Editor-in-Chief CLAIBORNE SMITH for the 2018 Kirkus Prize! This year’s finalists were chosen from 604 young read- [email protected] ers’ literature titles, 295 fiction titles, 294 nonfiction titles, and 90 Indie titles. The Vice President of Marketing SARAH KALINA three winning books will be announced in Austin, Texas, on Thursday, Oct. 25. [email protected] Winners in the three categories will receive $50,000 each, making the Kirkus Managing/Nonfiction Editor Prize one of the richest annual literary awards in the world. Books become eligible ERIC LIEBETRAU [email protected] by receiving a starred review from . Three panels of judges, com- Kirkus Reviews Fiction Editor posed of nationally respected writers and highly regarded booksellers, librarians, LAURIE MUCHNICK and Kirkus critics, select the Kirkus Prize finalists and winners. Thanks to the [email protected] Children’s Editor judges for their hard work! VICKY SMITH Claiborne Smith [email protected] The finalists for the 2018 Kirkus Prize are: Young Adult Editor LAURA -

Ellis & Associates, Inc

INTERNATIONAL LIFEGUARD Training Program Manual 5th Edition Meets ECC, MAHC, and OSHA Guidelines Ellis & Associates, Inc. 5979 Vineland Rd. Suite 105 Orlando, FL 32819 www.jellis.com 800-742-8720 Copyright © 2020 by Ellis & Associates, Inc. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated in writing by Ellis & Associates, the recipient of this manual is granted the limited right to download, print, photocopy, and use the electronic materials to fulfill Ellis & Associates lifeguard courses, subject to the following restrictions: • The recipient is prohibited from downloading the materials for use on their own website. • The recipient cannot sell electronic versions of the materials. • The recipient cannot revise, alter, adapt, or modify the materials. • The recipient cannot create derivative works incorporating, in part or in whole, any content of the materials. For permission requests, write to Ellis & Associates, addressed “Attention: Permissions Coordinator,” at the address above. Disclaimer: The procedures and protocols presented in this manual and the course are based on the most current recommendations of responsible medical sources, including the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) Consensus Guidelines for CPR, Emergency Cardiovascular Care (ECC) and First Aid, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) standards 1910.151, and the Model Aquatic Health Code (MAHC). The materials have been reviewed by internal and external field experts and verified to be consistent with the most current guidelines and standards. Ellis & Associates, however, make no guarantee as to, and assume no responsibility for, the correctness, sufficiency, or completeness of such recommendations or information. Additional procedures may be required under particular circumstances. Ellis & Associates disclaims all liability for damages of any kind arising from the use of, reference to, reliance on, or performance based on such information. -

"Archie's Girls?" Betty, Veronica, and the Rise of American Youth Culture, 1941-1950

ABSTRACT "ARCHIE'S GIRLS?" BETTY, VERONICA, AND THE RISE OF AMERICAN YOUTH CULTURE, 1941-1950 by Caroline Elizabeth Johnson This thesis uses the characters of Betty and Veronica of the Archie Comic series to explore the roles of adolescent females during the 1940s in the United States. The author utilizes feminist and art theory as well as relevant literature to argue that the writers of Archie Comics reflect and reify teenage experience through the characters of Betty and Veronica. Themes addressed include labor roles, dating habits, as well as teen involvement in consumer culture. By addressing the role of adolescent experience, the author hopes to expand conversations regarding women during the 1940s to include the impact of youth culture. The author concludes by suggesting Betty and Veronica represent a larger trend in American society regarding the way in which young women are conditioned to think and act in a particular manner via popular culture. "ARCHIE’S GIRL’S?” BETTY, VERONICA, AND THE RISE OF AMERICAN YOUTH CULTURE, 1941-1950 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Caroline Elizabeth Johnson Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2016 Advisor: Dr. Kimberly Hamlin Reader: Dr. Mark Mckinney Reader: Dr. Stephen Norris ©2016 Caroline Elizabeth Johnson This Thesis titled "ARCHIE’S GIRL’S?” BETTY, VERONICA, AND THE RISE OF AMERICAN YOUTH CULTURE, 1941-1950 by Caroline Elizabeth Johnson has been approved for publication by The College of Arts and Science and Department of History ____________________________________________________ Dr. Kimberly Hamlin ______________________________________________________ Dr. -

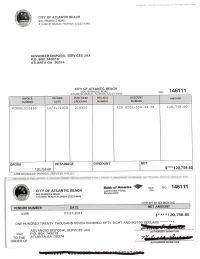

Vpffiveraimilerfeee DISPOSAL SERVICES JAX ADVANCED AUTHORIZED SIGNATURE PAY P

REORDER 905. U. S. PATENT NO. 5538290, 5575508, 5641183. 0765353, 5984364. 0030000 fat A CITY OF ATLANTIC BEACH ir'-' 800 SEMINOLE ROAD ATLANTIC BEACH, FLORIDA 32233- 4445 riE ADVANCED DISPOSAL SERVICES JAX P. O. BOX 743019 ATLANTA GA 30374 CITY OF ATLANTIC BEACH 800 SEMINOLE ROAD N0 146111 ATLANTIC BEACH, FLORIDA 32233- 4445 ACG£ 3UNT INVOICEiNiMINVOICEnnPl1RCi{ ASE':^ PROJECT AMOUN 534- 34- 01 120, 758. 60 P00001522490 12/ 31/ 2020 210320 420- 4201- NET GROSS RETAINAGE DISCOUNT 120, 758. 60 120, 758. 60 4496 ADVANCED DISPOSAL SERVICES JAX, LLC KNIGHT& FINGERPRINT WATERMARK ON THE BACK- HULL) AT ANGLE TO VIEW COLORED BORDER AND BACKGROUND PLUS A THIS CHECK IS VOID WITHOUT A 00' Bank of America '.: 63- 4 NO. 146111 Jacksonville, Florida 630 t CITY OF ATLANTIC BEACH Member FDIC 800 SEMINOLE ROAD ATLANTIC BEACH, FLORIDA 32233- 4445 VOID AFTER SIX MONTHS it i4it3 i.:11UI$ BEk1; DATE N.ET AM[ 3UNT: i 4496 01/ 21/ 2021 4 120, 758. 60 ONE HUNDRED TWENTY THOUSAND SEVEN HUNDRED FIFTY EIGHT AND 60/ 100 DOLLARS VPffiveraimilerfeee DISPOSAL SERVICES JAX ADVANCED AUTHORIZED SIGNATURE PAY P. O. BOX 743019 ATLANTA GA 30374 TO THE ORDER OF AUTHORIZED SIGNATURE S^?" 1fr'1( 7,..„, CITY OF ATLANTIC BEACH its PURCHASING PURCHASE PHONE ( 904) 247 5880 ORDERI' i_.).„,.. t FAX ( 904) 247- 5819 P. O. NUMBER DATE J ; . 210320 11/ 18/ 20 l THIS P. O. NUMBER MUST APPEAR ON ALL INVOICES PACKING SLIPS, LABELS, BILLS OF LADING AND CORRESPONDENCE VENDOR: SHIP TO: ADVANCED DISPOSAL SERVICES JAX CITY OF ATLANTIC BEACH 7580 PHILLIPS HIGHWAY ATTN: PUBLIC WORKS DEPT JACKSONVILLE, FL 32256 1200 SANDPIPER LANE ATLANTIC BEACH, FL 32233 VENDOR# DATE NEEDED TERMS REQUISITIONED BY 4496 11/ 09/ 20 NET SHOWMAN/ WILLIAMS F. -

Catalog 2003–2004 2

Catalog 2003–2004 2 On the pages that follow you will find information which will be invalu- able to you as you plan your academic program at Virginia Wesleyan Col- lege. They contain descriptions of the numerous educational options available to you along with essential information on academic regulations, student life, financial aid, career planning, and other aspects of college life. In many ways, the information can serve as your guide to academic success. Read this catalog carefully, refer to it frequently, and use it to track your progress. Whether you are a recent high school graduate, an adult student, a col- lege transfer, a veteran, or an international student, Virginia Wesleyan at- tempts to meet your educational needs and addresses them here. Take a moment to review the Table of Contents so that you are familiar with this publication. Dr. Stephen S. Mansfield Prospective students will have a particular interest in reading the fol- lowing sections: “Virginia Wesleyan College: A Special Place,” “A Frame- work For Your Future,” “Your Commitment to Virginia Wesleyan,” “Financial Information–Education Within Your Reach,” and other sections as well. Current students should become familiar with the section entitled “A Framework For Your Future,” which defines graduation requirements. Other sections of special interest to you are those on “Career Ser- vices–Planning Your Future” and “Programs and Courses–Design Your Future.” Please feel free to call on me whenever I am needed; call on your adviser frequently. The section of the catalog entitled “College Beyond Books” is your guide to numerous student services. Best wishes to you for a rewarding educational experience at Virginia Wesleyan. -

M-PIE Soup Supper

The Fairbury OURNAL-Your Community. Your Paper. EWS WWW.FAIRBURYJOURNALNEWS.COMJ FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 1, 2019 N 13 PAGES | DIGITAL VOL. 3 | NO. 26 M-PIE Soup Supper Photo by Christina Weidner/fairburyjournalnews.com M-PIE Hosts Annual Soup Supper—Meridian Partners in Education (M-PIE) hosted their annual soup supper Tuesday, January 29 from 5-8 pm during the Meridian vs. High Plains Community basketball games. Area Superintendents Weigh In On Current Legislation Session With the Nebraska Legislature in full “I know the Governor has already said swing, education is always one of the major something about putting more into the issues each session. Area superintendents Property Tax Credit fund. That works to a weigh in on what this session could bring to degree, but it does not solve the “inequities” the world of education in Nebraska. of the “3-legged stool.” In my mind the only way to address the 3-legged stool, is a tax Stephen Grizzle noted that the legislation shift of some sort. I believe there is a grow- will hold several crucial bills. ing sense of urgency in the legislature to “This will be a pivotal year, I believe. If you pass legislation to balance that out. How- look at the committee chair elections, you ever, it will have to pass a veto as the Gov- see more parity...meaning of the 17 com- ernor has made it clear that, in his mind, mittees, Republicans are chairs of 12 and a tax shift is the equivalence to a tax in- Democrats 5. This may seem small, but it is crease,” Grizzle said. -

Previews #323 (Vol

PREVIEWS #323 (VOL. XXV #8, AUG15) PREVIEWS PUBLICATIONS PREVIEWS #325 OCTOBER 2015 SAME GREAT PREVIEWS! NEW LOWER PRICE: $3.99! Since 1988, PREVIEWS has been your ultimate source for all of the comics and merchandise to be available from your local comic book shop… revealed up to two months in advance! Hundreds of comics and graphic novels from the best comic publishers; the coolest pop-culture merchandise on Earth; plus PREVIEWS exclusive items available nowhere else! Now more than ever, PREVIEWS is here to show the tales, toys and treasures in your future! This October issue features items scheduled to ship in December 2015 and beyond. Catalog, 8x11, 500+pg, PC SRP: $3.99 MARVEL PREVIEWS VOLUME 2 #39 Each issue of Marvel Previews is a comic book-sized, 120-page, full-color guide and preview to all of Marvel’s upcoming releases — it’s your #1 source for advanced information on Marvel Comics! This October issue features items scheduled to ship in December 2015 and beyond. FREE w/Purchase of PREVIEWS Comic-sized, 120pg, FC SRP: $1.25 PREVIEWS #325 CUSTOMER ORDER FORM — OCTOBER 2015 PREVIEWS makes it easy for you to order every item in the catalog with this separate order form booklet! This October issue features items scheduled to ship in December 2015 and beyond. Comic-sized, 62pg, PC SRP: PI COMICS SECTION PREMIER VENDORS DARK HORSE COMICS ABE SAPIEN #27 Mike Mignola (W/Cover), Scott Allie (W), Alise Gluškova (A/C), and Dave Stewart (C) Abe’s memories of his life as a man in the nineteenth century come to the surface as secret societies fight over an object that could prove the true origins of the human race! FC, 32 pages SRP: $3.50 B.P.R.D.