Jim Crow at the Beach: an Oral and Archival History of the Segregated Past at Homestead Bayfront Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20 Adopted Budget and Multi‐Year Capital Plan Parks, Recreation and Open Spaces FY 2019‐20 Ad

FY 2019 ‐ 20 Adopted Budget and Multi‐Year Capital Plan Parks, Recreation and Open Spaces The Parks, Recreation and Open Spaces (PROS) Department builds, operates, manages and maintains one of the largest and most diverse park systems in the country consisting of over 270 parks and over 13,800 acres of passive and active park lands and natural areas that serve as the front line for resiliency and improved health solutions. The Department’s five strategic objectives and priority areas include fiscal sustainability, placemaking/design excellence, health and fitness, conservation and stewardship and performance excellence. The Department provides opportunities for health, happiness and prosperity for residents and visitors of Miami‐Dade County through the Parks & Open Spaces Master Plan, consisting of a connected system of parks, public spaces, natural and historic resources, greenways, blue‐ways and complete streets, guided by principles of access, equity, beauty, sustainability and multiple benefits. The Department operates as both a countywide park system serving 2.8 million residents and as a local parks department for the unincorporated area serving approximately 1.2 million residents. The Department acquires, plans, designs, constructs, maintains, programs and operates County parks and recreational facilities; provides summer camps, afterschool and weekend programs for youth; manages 44 competitive youth sports program partners; provides programs for active adults, the elderly and people with disabilities; and provides unique experiences at Zoo Miami and seven Heritage Parks: Crandon, Deering Estate, Fruit and Spice, Greynolds, Haulover, Homestead Bayfront and Matheson Hammock Park. Additionally, PROS provides various community recreational opportunities including campgrounds, 17 miles of beaches, 304 ballfields, tennis, volleyball, and basketball courts, an equestrian center, picnic shelters, playgrounds, fitness zones, swimming pools, recreation centers, sports complexes, a gun range and walking and bicycle trails. -

South-Florida-Alcohol-Liquor-Licensing-A-Snapshot.Pdf

South Florida Alcohol and Liquor Licensing – A Snapshot By Valerie L. Haber, Miami Alcohol Law and Food Law Attorney Many clients come to GrayRobinson’s Alcohol Law Group with the misconception that getting a beer and wine license, or liquor license in South Florida, (including the City of Miami, Miami Beach, Fort Lauderdale, Broward County or Palm Beach County,) will be a straightforward process. Before reaching out to us, these clients often find themselves stuck in a holding pattern with state or local agencies, which oftentimes have convoluted and burdensome requirements that must be met before a state alcohol license can be issued. Complicating matters further, local municipal requirements vary greatly. For example, the City of Miami Beach, which includes South Beach, requires that you obtain a Certificate of Use and Business Tax Receipt before you can apply for your state alcohol beverage license. The City of Miami, which includes downtown Miami, the Design District, Wynwood, Coconut Grove, and the Calle Ocho area, requires that multiple local inspections be performed before their zoning department will sign off on a state alcohol beverage application. Navigating these complexities can be tough, but completely manageable once you understand important aspects of the licensing process. Florida Liquor License and Beer and Wine License Types: As a starting point, if you are a new business in South Florida wanting to sell alcohol beverages, including beer, wine, or spirits, you need to determine what type of alcohol or liquor license is appropriate for your intended operations. There are multiple Florida alcohol license types available to you through the Florida Division of Alcoholic Beverages and Tobacco (the “DABT”), including: Beer and wine for on-premise consumption (2COP license): A “2COP” license allows the licensee to sell beer and wine for on-premise consumption. -

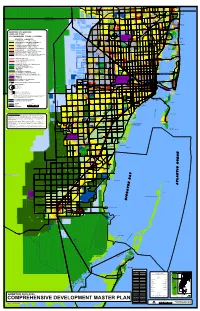

Comprehensive Development Master Plan (CDMP) and Are NAPPER CREEK EXT Delineated in the Adopted Text

E E E A I E E E E E V 1 E V X D 5 V V V V I I V A Y V A 9 A S A A A D E R A 7 I A W 7 2 U 7 7 2 K 7 O 3 7 H W 7 4 5 6 P E W L 7 E 9 W T W N F V W E V 7 W N W N W A W N V 2 A N N 5 N N 7 A 7 S 7 0 1 7 I U 1 1 8 W S DAIRY RD GOLDEN BEACH W SNAKE CREEK CANAL IVE W N N N NW 202 ST AVENTURA BROWARD COUNTY MAN C LEH SWY OMPIAA-MLOI- C K A MIAMI-DADE COUNTY DAWDEES T CAOIRUPNOTYR T NW 186 ST MIAMI GARDENS SUNNY ISLES BEACH E K P T ST W A NE 167 NORTH MIAMI BEACH D NW 170 ST O I NE 163 ST K R SR 826 EXT E E E O OLETA RIVER E V C L V STATE PARK A A H F 0 O 2 1 B 1 ADOPTED 2015 AND 2025 E E E T E N R X N D E LAND USE PLAN * NW 154 ST 9 R Y FIU/BUENA MIAMI LAKES S W VISTA H 1 FOR MIAMI-DADE COUNTY, FLORIDA OPA-LOCKA E AIRPORT I S HAULOVER X U I PARK D RESIDENTIAL COMMUNITIES NW 138 ST OPA-LOCKA W ESTATE DENSITY (EDR) 1-2.5 DU/AC G ESTATE DENSITY W/ ONE DENSITY INCREASE (DI-1) R NORTH MIAMI BAL HARBOUR A T BR LOW DENSITY (LDR) 2.5-6 DU/AC IG OAD N BAY HARBOR ISLANDS HIALEAH GARDENS Y CSW LOW DENSITY W/ ONE DENSITY INCREASE (DI-1) Y AMELIA EARHART PKY E PARK E V E E BISCAYNE PARK E V LOW-MEDIUM DENSITY (LMDR) 6-13 DU/AC V A V V V A D I A A A SURFSIDE MDOC A V 7 M LOW-MEDIUM DENSITY W/ ONE DENSITY INCREASE (DI-1) 2 L 2 7 NORTH 2 1 A B INDIAN CREEK VILLAGE I 2 E E W W E E M W V MEDIUM DENSITY (MDR) 13-25 DU/AC N N N W N V N A N Y NW 106 ST N A 6 MEDIUM DENSITY W/ ONE DENSITY INCREASE (DI-1) A HIALEAH C S E IS N MEDIUM-HIGH DENSITY (MHDR) 25-60 DU/AC N B I MEDLEY L L HIGH DENSITY (HDR) 60-125 DU/AC OR MORE/GROSS AC E MIAMI SHORES O V E C A TWO DENSITY -

Wynwood Development Table of Contents 03 Project Overview

TOTAL AREA: 60,238 SQ.FT. Wynwood Development Table of Contents 03 Project Overview 15 Conceptual Drawings 17 Location 20 Demographics 23 Site Plan 26 Building Efficiency 29 RelatedISG Project Overview Project This featured property is centrally located in one of Miami’s hottest and trendiest neighborhood, Wynwood. The 60,238 SF site offers the unique possibility to develop one of South Florida’s most ground-breaking projects. There has only been a select amount of land deals in the past few years available in this neighborhood, and it is not common to find anything over 20,000 SF on average. With its desirable size and mixed use zoning, one can develop over 300 units with a retail component. Wynwood has experienced some of the highest rental rates of any area of South Florida, exceeding $3 per SF, and retail rates exceeding $100 SF. As the area continues to grow and evolve into a world renowned destination, it is forecasted that both residential and retail rental rates will keep increasing. Major landmark projects such as the Florida Brightline and Society Wynwood, as well as major groups such as Goldman Sachs, Zafra Bank, Thor Equity and Related Group investing here, it is positioned to keep growing at an unprecedented rate. Name Wynwood Development Style Development Site Location Edgewater - Miami 51 NE 22th Street Miami, FL 33137 Total Size 60,238 SQ. FT. (1.3829 ACRES) Lot A 50 NE 23nd STREET Folio # 01-3125-015-0140 Lot B 60 NE 23nd STREET Folio 01-3125-011-0330 Lot C 68 NE 23rd STREET Folio 01-3125-011-0320 Lot D 76 NE 23rd STREET Folio 01-3125-011-0310 Lot E 49 NE 23rd STREET Folio 01-3125-015-0140 Lot F 51 NE 23rd STREET Folio 01-3125-015-0130 Zoning T6-8-O URBAN CORE TRANSECT ZONE 04 Development Regulations And Area Requirements DEVELOPMENT REGULATIONS AND AREA REQUIREMENTS DESCRIPTION VALUE CODE SECTION REQUIRED PERMITTED PROVIDED CATEGORY RESIDENTIAL PERMITTED COMMERCIAL LODGING RESIDENTIAL COMMERCIAL LODGING RESIDENTIAL LODGING PERMITTED GENERAL COMMERCIAL PERMITTED LOT AREA / DENSITY MIN.5,000 SF LOT AREA MAX. -

Teacher's Guide

National Park Service Aram Demirjian, Music Director Great Smoky Mountains National Park Sheena McCall Young People’s Concerts: Fall 2020 TEACHER’S GUIDE THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK (INSIDE COVER) Table of Contents PROGRAM REPERTOIRE Program Notes: Our Composers and their Music “Reel Time” from Southern Harmony Higdon, “Reel Song” ................................................. 2 by Jennifer Higdon Vivaldi, “Autumn” ...................................................... 2 Rimsky-Korsakov, “Flight of the Bumblebee” ......... 3 “Autumn,” III. Allegro Debussy, “Clair de Lune” .......................................... 3 from The Four Seasons Variego, Songs in Light: Firefly Music ...................... 4 by Antonio Vivaldi Joplin, The Entertainer .............................................. 4 “Flight of the Bumblebee” Crowe, How Birds Came Into the World .................. 5 from The Tale of Tsar Saltan Traditional/Arr. Robertson and Coolidge, by Rimsky-Korsakov Cherokee Morning Song ...................................... 5 “Clair de Lune” from Bergamasque Bryant & Bryant, Rocky Top ...................................... 6 by Claude Debussy Online Audio Link ............................................................ 6 Songs in Light: Firely Music by Jorge Variego Lessons: Cherokee Morning Song/ Moon Observation... .................................................. 7-13 Program repertoire and artists subject to change The Entertainer by Scott Joplin Activities & Resources for Teachers/ Audience Job Description ............................................ -

Redland Tropical Trail Brochure

Spend a Night on the Trail & More. ESCAPE the traffic and noise of the city and EXPLORE the agri-tourism south Miami-Dade offers. Come ENJOY Miami-Dade’s countryside. 1 Value Place Lodging Homestead’s Popular Extended Stay Lodging 2750 NE 8th St., Homestead 33033 305 245 5000 • 1 877 497 5223 • TPKE Exit 2 • TPKE exit 2 Corner of Campbell Dr. (SW 312 St.) & Kingman Rd (152nd Ave.) Because our studios are very comfortable, secure and affordable, Value Place encourages you and your visiting family members to extend your stay a week or more with us and visit every site in this brochure, while enjoying Nestled between the unique treasures of the natural wonders of South Florida. Youʼll appreciate how we value our Everglades National Park and Biscayne guests, and how our community treasures your visit! National Park lies an area rich in history, beauty, tropical climate and tempting food. 2 Shiver’s Bar-B-Q 28001 S. Dixie Hwy Discover acres of incredible tropical fruits and Homestead, Fl 33033 vegetables, stunning orchids and beautiful (305) 248-9475 • www.shiversbbq.com One of South Floridaʼs best kept secrets. bonsai trees.Taste exotic fruit wines, luscious Serving authentic hickory smoked BBQ for over 60 years! Family owned homemade milkshakes, fabulous Italian and and operated, Shiverʼs offers smoked pulled pork, beef brisket, baby back ribs, beef ribs, and more. Come enjoy some great BBQ and local cuisine. Encounter wild alligators and Southern hospitality at Shiverʼs Bar-B-Q! uncaged monkeys, explore a love story in stone, shop and dine in a lush tropical garden with 3 The Little Farm fountains and sculptures, and catch an exciting Gentle farm animals for enjoyment and education airboat ride into the Florida Everglades. -

Front Desk Concierge Book Table of Contents

FRONT DESK CONCIERGE BOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS I II III HISTORY MUSEUMS DESTINATION 1.1 Miami Beach 2.1 Bass Museum of Art ENTERTAINMENT 1.2 Founding Fathers 2.2 The Wolfsonian 3.1 Miami Metro Zoo 1.3 The Leslie Hotels 2.3 World Erotic Art Museum (WEAM) 3.2 Miami Children’s Museum 1.4 The Nassau Suite Hotel 2.4 Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) 3.3 Jungle Island 1.5 The Shepley Hotel 2.5 Miami Science Museum 3.4 Rapids Water Park 2.6 Vizcaya Museum & Gardens 3.5 Miami Sea Aquarium 2.7 Frost Art Museum 3.6 Lion Country Safari 2.8 Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) 3.7 Seminole Tribe of Florida 2.9 Lowe Art Museum 3.8 Monkey Jungle 2.10 Flagler Museum 3.9 Venetian Pool 3.10 Everglades Alligator Farm TABLE OF CONTENTS IV V VI VII VIII IX SHOPPING MALLS MOVIE THEATERS PERFORMING CASINO & GAMING SPORTS ACTIVITIES SPORTING EVENTS 4.1 The Shops at Fifth & Alton 5.1 Regal South Beach VENUES 7.1 Magic City Casino 8.1 Tennis 4.2 Lincoln Road Mall 5.2 Miami Beach Cinematheque (Indep.) 7.2 Seminole Hard Rock Casino 8.2 Lap/Swimming Pool 6.1 New World Symphony 9.1 Sunlife Stadium 5.3 O Cinema Miami Beach (Indep.) 7.3 Gulfstream Park Casino 8.3 Basketball 4.3 Bal Harbour Shops 9.2 American Airlines Arena 6.2 The Fillmore Miami Beach 7.4 Hialeah Park Race Track 8.4 Golf 9.3 Marlins Park 6.3 Adrienne Arscht Center 8.5 Biking 9.4 Ice Hockey 6.4 American Airlines Arena 8.6 Rowing 9.5 Crandon Park Tennis Center 6.5 Gusman Center 8.7 Sailing 6.6 Broward Center 8.8 Kayaking 6.7 Hard Rock Live 8.9 Paddleboarding 6.8 BB&T Center 8.10 Snorkeling 8.11 Scuba Diving 8.12 -

Price Schedule Lift Stations Maintenance Services

Solicitation No: FB-00706 SECTION 4: PRICE SCHEDULE LIFT STATIONS MAINTENANCE SERVICES GROUP 2: OTHER MIAMI-DADE COUNTY LIFT STATIONS Service Description: Monthly preventive maintenance tasks at lift station locations as per section 3.11.2 Estimated Annual Item No. Quantity Lift Station Location Unit Price Parks, Recreation and Open Spaces Department A.D. (Doug) Barnes Park 3701 SW 70th Ave Miami, Florida 33155 1 12 Months PS #971 $30 Per Month Amelia Earhart Park 401 E. 65th Street Hialeah, Florida 33014 2 12 Months PS #984-A $30 Per Month Amelia Earhart Park 401 E. 65th Street Hialeah, Florida 33014 3 12 Months PS #984-B $30 Per Month Arcola Lakes Park 1301 NW 83rd Street Miami, Florida 33147 4 12 Months PS #1254 $30 Per Month Black Point Park & Marina 24775 SW 87th Ave Homestead, Florida 33032 5 12 Months PS #1097-A $30 Per Month Black Point Park & Marina 24775 SW 87th Ave Homestead, Florida 33032 6 12 Months PS #1097-B $30 Per Month Camp Matecumbe 11400 SW 137th Ave Miami, Florida 33186 7 12 Months PS #382 $30 Per Month Continental Park 10100 SW 82nd Ave Miami, Florida 33156 8 12 Months PS #1044 $30 Per Month Solicitation No: FB-00706 Estimated Annual Item No. Quantity Lift Station Location Unit Price Parks, Recreation, and Open Spaces Department (Continued) Country Club of Miami 6801 NW 186th Street Hialeah, Florida 33015 9 12 Months PS #397 $30 Per Month Crandon Park - Cabanas 4000 Crandon Blvd Key Biscayne, Florida 33149 10 12 Months PS #972-A $30 Per Month Crandon Park - Cabanas 4000 Crandon Blvd Key Biscayne, Florida 33149 11 -

1973-Iceland.Pdf

-----=ca=rn=-.....z:-c, wrn=-:- --. n ===N::ll:-cI - .. • ~ en Place I Monday, June 18 I Tuesday, June 19 I Wednesday, Ju'!e 20 I I Thursday, June 21 I Friday, June 22 I Saturday, June 23 1 Sunday, June 24 10.00--12.00 10.00-12.00 10.00-12.00 Hotel General Assembly General Assembly General Assembly Loftleidir (if necessary) 14.00- 16.00 14.00-16.00 General Assembly General Assembly 12.00 Lvric Arts Trio Charpentier: --- The Symphony --- Nordic 17.00 17.00 22.00 House Norwegian Wood- Harpans Kraft Nonvegian jazz Wind Quintet from Sweden Bibalo, Berge, Salmenhaara, W elin, Mortensen, Nordheim - - -·- [_____ - 20.30 20.00 17.00 14.00 14.00 14.00 Miklatun Reception Tenidis, Kopelent TapeMusic Tape Music Tape Music Tape Music T6masson, Hall- Gilboa, Schurink grlmsson, Leifs Lambrecht, 20.00 20.00 17.00 Benhamou, Kim, Lyric Arts Trio German Trio Gaudeamus Tokunaga, Ishii, Doh!, Quartet Thommesen Zender, de Leeuw I Zimmermann, Raxach I Karkoschka, I Lutoslawski Haubenstock- Ramati, Hoffmann I I ---- --- -- - ' Exhibition of scores sent in by sections daily, at Miklatun --- - ISCM --- --- -- Hask6\abi6 21.00 Iceland Symphony Orchestra ThorarinssQn, Mallnes, Stevens, Endres, Gentilucci, Lachenmann, Krauze - - - - - -- -- -- ~ -- - State 17.00 Radio Icelandic Music on Tape - - - --- - --- -- Arnes Recital: Aitken/ Haraldsson I The President of the ISCM The President of the Icelandic Section In whatever way the 1973 Music Day may enter the history of It is a great pleasure for the Icelandic Section of the ISCM the ISCM, surely it will be remembered as the most Northern to receive the delegates of the sister organisations to the General point ever reached by the Society. -

Miami-Miami Beach-Kendall, Florida

HUD PD&R Housing Market Profiles Miami-Miami Beach-Kendall, Florida Quick Facts About Miami-Miami Beach-Kendall By T. Michael Miller | As of June 1, 2019 Current sales market conditions: balanced Overview Current apartment market conditions: balanced The Miami-Miami Beach-Kendall Metropolitan Division (hereafter, Miami-Dade County), on the southeastern coast of Florida, is Known as a destination for beautiful beaches coterminous with Miami-Dade County. The coastal location makes and eclectic nightlife, the Miami HMA attracted Miami-Dade County an attractive destination for trade and tourism. an estimated 15.9 million visitors in 2017, which During 2018, nearly 8.78 million tons of cargo passed through had an economic impact of more than $38.9 PortMiami, an increase of 2 percent from 2017. The number of billion on the HMA’s economy (Greater Miami cruise passengers out of PortMiami also hit record highs, with Convention & Visitors Bureau). 5.3 million passengers sailing during 2017, up nearly 5 percent from 2016 (Greater Miami Convention & Visitors Bureau). y As of June 1, 2019, the population of Miami-Dade County is estimated at 2.79 million, reflecting an average annual increase of 24,000, or 0.9 percent, since 2016 (U.S. Census Bureau population estimates as of July 1). Net in-migration averaged 9,050 people annually during the period, accounting for 38 percent of the population growth. y From 2011 to 2016, population growth was more rapid because of stronger international in-migration. Population growth averaged 30,550 people, or 1.2 percent, annually, and net in-migration averaged 17,900 people annually, which was 59 percent of the growth. -

Fitzpatrick's Miami River Plantation

Richard Fitzpatrick's South Florida, 1822-1840 Part II: Fitzpatrick's Miami River Plantation By Hugo L. Black III* During the 1820's, most of the land in southeast Florida was owned by the government. By 1825, only six private claims from the Spanish period had been validated: the Polly Lewis, Jonathan Lewis, and Rebecca Hagan (Egan) Donations on the South side of the Miami River, the James Hagan (Egan) Donation on the North side of the Miami River, the Mary Ann Davis Donation on Key Biscayne, and the Frankee Lewis Donation on the New River.1 Notwithstanding the lack of settlement, even during this period, southeast Florida's suitability for plantations was recognized. James Egan emphasized this suitability in the following advertisement run on numerous occasions in the Key West Register during 1829, in which he offered his land on the Miami River for Sale: For Sale A Valuable Tract of LAND Near Cape Florida Situated on the Miami River. The Land is very good and will produce Sugar Cane and Sea Island Cotton, equal if not superior to any other part of the *Hugo Black, III, is a resident of Miami, a former state legislator, a graduate of Yale, and presently attending law school at Stanford University. This is the second part of an article written as a senior paper at Yale. For Part I see Tequesta, XL. 34 TEQUESTA Territory. There is at present a number of bearing Banana and Lime trees and the fruit is inferior to none raised in the Island of Cuba. The forest growth consists principally of Live Oak, Red Bay and Dog Wood. -

95 Express Route 106 Weekdays

Reading a Timetable - It’s Easy 1. The map shows the exact bus route. Broward County Transit 2. Major route intersections are called time points. Time points are shown with the symbol . 3. The timetable lists major time points for bus route. 95 EXPRESS Listed under time points are scheduled departure times. 4. Reading from left to right, indicates the time for ROUTE 106 each bus trip. MIRAMAR 5. Arrive at the bus stop five minutes early. Buses operate as close to published timetables as traffic WEEKDAY SCHEDULE conditions allow. Miramar Regional Park to Civic Center/ Health District and Culmer Metrorail Station Information: 954-357-8400 Effective 8/8/21 Hearing-speech impaired/TTY: 954-357-8302 This publication can be made available in alternative formats upon request by contacting 954-357-8400 or TTY 954-357-8302. This symbol is used on bus stop signs to indicate accessible bus stops. New Schedule Monday – Friday • Face Covering Required • Maintain Social Distancing Real Time Bus Information MyRide.Broward.org BROWARD COUNTY BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS An equal opportunity employer and provider of services. 3,500 copies of this public document were promulgated at a gross cost of Broward.org/BCT $604, or $.173 per copy, to inform the public about the Transit Division’s schedule and route information. Printed 8/21 954-357-8400 SOUTHBOUND • Miramar Park & Ride NORTHBOUND • Culmer Metrorail to Culmer Metrorail Station Station to Miramar Park & Ride CULMER METRORAIL STATION 14 STREET & 12 AVENUE MIRAMAR PKWY & FLAMINGO RD MIRAMAR PARK &