Fitzpatrick's Miami River Plantation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impeachment in Florida

Florida State University Law Review Volume 6 Issue 1 Article 1 Winter 1978 Impeachment in Florida Frederick B. Karl Marguerite Davis Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the President/Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation Frederick B. Karl & Marguerite Davis, Impeachment in Florida, 6 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 1 (1978) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol6/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 6 WINTER 1978 NUMBER 1 IMPEACHMENT IN FLORIDA FREDERICK B. KARL AND MARGUERITE DAVIS TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. HISTORY OF IMPEACHMENT AUTHORITY ..... 5 II. EFFECTS OF IMPEACHMENT ................... 9 III. GROUNDS FOR IMPEACHMENT .................. 11 IV. IMPEACHMENT FOR ACTS PRIOR TO PRESENT TERM OF OFFICE .................... 30 V. JUDICIAL REVIEW OF IMPEACHMENT PROCEEDINGS 39 VI. IMPEACHMENT PROCEDURE: THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ..................... ........ 43 VII. IMPEACHMENT PROCEDURE: THE SENATE ......... 47 VIII. IMPEACHMENT ALTERNATIVES .................... 51 A. CriminalSanctions .......................... 52 B . Incapacity ........ ... ... ............... 53 C. Ethics Commission ......................... 53 D. Judicial QualificationsCommission ........... 53 E . B ar D iscipline .............................. 54 F. Executive Suspension ........................ 55 IX . C ON CLUSION ................................... 55 X . A PPEN DIX ....... ............................ 59 2 FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 6:1 IMPEACHMENT IN FLORIDA FREDERICK B. KARL* AND MARGUERITE DAVIS** What was the practice before this in cases where the chief Magis- trate rendered himself obnoxious? Why recourse was had to assas- sination in wch. -

The Judicial Branch

The Judicial Branch 150 The Judicial System 159 The Supreme Court 168 Other Courts and Commissions 173 Judicial Milestones 149 (Reviewed by editorial staff November 2013) The Judicial System B. K. Roberts* “The judicial power shall be vested in a supreme court, district courts of appeal, circuit courts and county courts. No other courts may be established by the state, any political subdivision or any municipality.” Article V, Section 1, Florida Constitution On March 14, 1972, the electors of Florida ap- rendered. We commonly say proved a revision of the judicial article of the State that the judicial power is the Constitution to give Florida one of the most mod- power to administer justice ern court systems in the nation. Section 1 of Article and that “equal justice under V provides that “The judicial power shall be vested law” is the supreme object of in a supreme court, district courts of appeal, circuit all courts that perform their courts and county courts. No other courts may be proper function. established by the state, any political subdivision or In those cases where the any municipality.” The revision eliminated 14 differ- Legislature may decide that, ent types of courts which had been created pursu- for matters of convenience or B. K. Roberts ant to the 1885 Constitution. Substituted for these for quicker or more efficient trial courts is a uniform (two appellate and two trial administration of a particular law, the determination courts) structure composed of the Supreme Court, of controversies arising under such law should be District Courts of Appeal, circuit courts, and county exercised, in the first instance, by a commission or courts. -

Price Schedule Lift Stations Maintenance Services

Solicitation No: FB-00706 SECTION 4: PRICE SCHEDULE LIFT STATIONS MAINTENANCE SERVICES GROUP 2: OTHER MIAMI-DADE COUNTY LIFT STATIONS Service Description: Monthly preventive maintenance tasks at lift station locations as per section 3.11.2 Estimated Annual Item No. Quantity Lift Station Location Unit Price Parks, Recreation and Open Spaces Department A.D. (Doug) Barnes Park 3701 SW 70th Ave Miami, Florida 33155 1 12 Months PS #971 $30 Per Month Amelia Earhart Park 401 E. 65th Street Hialeah, Florida 33014 2 12 Months PS #984-A $30 Per Month Amelia Earhart Park 401 E. 65th Street Hialeah, Florida 33014 3 12 Months PS #984-B $30 Per Month Arcola Lakes Park 1301 NW 83rd Street Miami, Florida 33147 4 12 Months PS #1254 $30 Per Month Black Point Park & Marina 24775 SW 87th Ave Homestead, Florida 33032 5 12 Months PS #1097-A $30 Per Month Black Point Park & Marina 24775 SW 87th Ave Homestead, Florida 33032 6 12 Months PS #1097-B $30 Per Month Camp Matecumbe 11400 SW 137th Ave Miami, Florida 33186 7 12 Months PS #382 $30 Per Month Continental Park 10100 SW 82nd Ave Miami, Florida 33156 8 12 Months PS #1044 $30 Per Month Solicitation No: FB-00706 Estimated Annual Item No. Quantity Lift Station Location Unit Price Parks, Recreation, and Open Spaces Department (Continued) Country Club of Miami 6801 NW 186th Street Hialeah, Florida 33015 9 12 Months PS #397 $30 Per Month Crandon Park - Cabanas 4000 Crandon Blvd Key Biscayne, Florida 33149 10 12 Months PS #972-A $30 Per Month Crandon Park - Cabanas 4000 Crandon Blvd Key Biscayne, Florida 33149 11 -

Jim Crow at the Beach: an Oral and Archival History of the Segregated Past at Homestead Bayfront Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Biscayne National Park Jim Crow at the Beach: An Oral and Archival History of the Segregated Past at Homestead Bayfront Park. ON THE COVER Biscayne National Park’s Visitor Center harbor, former site of the “Black Beach” at the once-segregated Homestead Bayfront Park. Photo by Biscayne National Park Jim Crow at the Beach: An Oral and Archival History of the Segregated Past at Homestead Bayfront Park. BISC Acc. 413. Iyshia Lowman, University of South Florida National Park Service Biscayne National Park 9700 SW 328th St. Homestead, FL 33033 December, 2012 U.S. Department of the InteriorNational Park Service Biscayne National Park Homestead, FL Contents Figures............................................................................................................................................ iii Acknowledgments.......................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 A Period in Time ............................................................................................................................. 1 The Long Road to Segregation ....................................................................................................... 4 At the Swimming Hole .................................................................................................................. -

Trade and Plunder Networks in the Second Seminole War in Florida, 1835-1842

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Trade and Plunder Networks in the Second Seminole War in Florida, 1835-1842 Toni Carrier University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Carrier, Toni, "Trade and Plunder Networks in the Second Seminole War in Florida, 1835-1842" (2005). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2811 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Trade and Plunder Networks in the Second Seminole War in Florida, 1835-1842 by Toni Carrier A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Brent R. Weisman, Ph.D. Robert H. Tykot, Ph.D. Trevor R. Purcell, Ph.D. Date of Approval: April 14, 2005 Keywords: Social Capital, Political Economy, Black Seminoles, Illicit Trade, Slaves, Ranchos, Wreckers, Slave Resistance, Free Blacks, Indian Wars, Indian Negroes, Maroons © Copyright 2005, Toni Carrier Dedication To my baby sister Heather, 1987-2001. You were my heart, which now has wings. Acknowledgments I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to the many people who mentored, guided, supported and otherwise put up with me throughout the preparation of this manuscript. To Dr. -

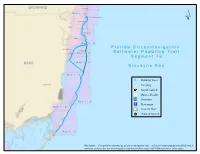

Segment 16 Map Book

Hollywood BROWARD Hallandale M aa p 44 -- B North Miami Beach North Miami Hialeah Miami Beach Miami M aa p 44 -- B South Miami F ll o r ii d a C ii r c u m n a v ii g a tt ii o n Key Biscayne Coral Gables M aa p 33 -- B S a ll tt w a tt e r P a d d ll ii n g T r a ii ll S e g m e n tt 1 6 DADE M aa p 33 -- A B ii s c a y n e B a y M aa p 22 -- B Drinking Water Homestead Camping Kayak Launch Shower Facility Restroom M aa p 22 -- A Restaurant M aa p 11 -- B Grocery Store Point of Interest M aa p 11 -- A Disclaimer: This guide is intended as an aid to navigation only. A Gobal Positioning System (GPS) unit is required, and persons are encouraged to supplement these maps with NOAA charts or other maps. Segment 16: Biscayne Bay Little Pumpkin Creek Map 1 B Pumpkin Key Card Point Little Angelfish Creek C A Snapper Point R Card Sound D 12 S O 6 U 3 N 6 6 18 D R Dispatch Creek D 12 Biscayne Bay Aquatic Preserve 3 ´ Ocean Reef Harbor 12 Wednesday Point 12 Card Point Cut 12 Card Bank 12 5 18 0 9 6 3 R C New Mahogany Hammock State Botanical Site 12 6 Cormorant Point Crocodile Lake CR- 905A 12 6 Key Largo Hammock Botanical State Park Mosquito Creek Crocodile Lake National Wildlife Refuge Dynamite Docks 3 6 18 6 North Key Largo 12 30 Steamboat Creek John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park Carysfort Yacht Harbor 18 12 D R D 3 N U O S 12 D R A 12 C 18 Basin Hills Elizabeth, Point 3 12 12 12 0 0.5 1 2 Miles 3 6 12 12 3 12 6 12 Segment 16: Biscayne Bay 3 6 Map 1 A 12 12 3 6 ´ Thursday Point Largo Point 6 Mary, Point 12 D R 6 D N U 3 O S D R S A R C John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park 5 18 3 12 B Garden Cove Campsite Snake Point Garden Cove Upper Sound Point 6 Sexton Cove 18 Rattlesnake Key Stellrecht Point Key Largo 3 Sound Point T A Y L 12 O 3 R 18 D Whitmore Bight Y R W H S A 18 E S Anglers Park R 18 E V O Willie, Point Largo Sound N: 25.1248 | W: -80.4042 op t[ D A I* R A John Pennekamp State Park A M 12 B N: 25.1730 | W: -80.3654 t[ O L 0 Radabo0b. -

Community Relations Plan

Miami International Airport Community Relations Plan Preface .............................................................................................................. 1 Overview of the CRP ......................................................................................... 2 NCP Background ............................................................................................... 3 National Contingency Plan .............................................................................................................. 3 Government Oversight.................................................................................................................... 4 Site Description and History ............................................................................. 5 Site Description .............................................................................................................................. 5 Site History .................................................................................................................................... 5 Goals of the CRP ............................................................................................... 8 Community Relations Activities........................................................................ 9 Appendix A – Site Map .................................................................................... 10 Appendix B – Contact List............................................................................... 11 Federal Officials .......................................................................................................................... -

Fla. Bar No: 797901 541 E

SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA CASE NO.: SC12 L.T. No.: 3D10-2415, 10-6837 ANTHONY MACKEY, Appellant, vs. STATE OF FLORIDA, Appellee. AMICUS CURIAE FLORIDA CARRY, INC.'S BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANT FLETCHER & PHILLIPS Eric J. Friday Fla. Bar No: 797901 541 E. Monroe St. STE 1 Jacksonville, FL 32202 Phone: 904-353-7733 Primary: [email protected] Secondary: [email protected] 1 I Table of Contents Table of Contents ......................................................................................................2 Table ofCitations......................................................................................................3 Interest ofAmicus Curiae .........................................................................................5 Summary ofArgument..............................................................................................5 Argument...................................................................................................................6 Possession of a firearm does not constitute reasonable suspicion of criminal activity. .................................................................................................7 Lawful activity while carrying should not be an affirmative defense. The state should be required to establish every element of the crime and that the statute at issue applies. .......................................................... 11 Legislative pronouncements and statutory history indicate an intent to protect Floridians' rights to keep and bear -

Crandon Park

Crandon Park Crandon Park is one of seven heritage parks acquired by Miami-Dade County. The park sits on a barrier island, with two miles of beach to the east, and Biscayne Bay to the west. Possessing a rich coastal environment the Park is home to a fossilized mangrove reef (unique in the world), a barrier island shoreline, sea grasses, protected wetlands, coastal hammocks and bird estuaries. Amenities include Crandon Gardens, a Nature Center, Marina, Golf Course, Tennis Center, picnic areas, bicycle/running paths, a pristine sandy beach, swimming, birdwatching and tot lot, to include a historic carousel all of which offer unparalleled recreational opportunities. Crandon Beach and the Bear Cut preserve are listed birding sites in the Great Florida Birding and Wildlife Viewing Trail guide [1]. Two and one half miles of road, located in the Park, were designated as a State historic highway by the State of Florida [2]. The north side of Key Biscayne, what’s known today, as Crandon Park, was purchased by Commodore William John Matheson, a wealthy aniline dye businessman, in 1908. He purchased 1,700 acres of land and created a coconut plantation at least twice as large as any other in the United States employing 42 workers by 1915. Thirty-six thousand coconut trees and a variety of other tropical fruits were planted and in 1921 he introduced the Malay Dwarf coconut to the United States. This is now the most common variety of coconut found in Florida. By 1933, the world price for coconut products had dropped to about two-fifths of its 1925 level, and the plantation stopped shipping. -

Authorization; Providing for Implementation; and Providing for an Effective Date

RESOLUTION NO. 2018-11 A RESOLUTION OF THE VILLAGE COT]NCIL OF THE VILLAGE OF KEY BISCAYNE, FLORIDA, SELECTING KIMLEY HORN AND ASSOCIATES, INC. FOR PROFESSIONAL ENGINEERING SERVICES FOR THE SAFE ROUTES TO SCHOOL PROJECT; PROVIDING FOR AUTHORIZATION; PROVIDING FOR IMPLEMENTATION; AND PROVIDING FOR AN EFFECTIVE DATE. WHEREAS, the Village of Key Biscayne ("Village") issued Request For Qualifications No. 2017-08-03 ("RFq", for professional engineering services ("Services") for the Village's Safe Routes to Schools project ("Project"); and WHEREAS, in response to the RFQ, the Village received six (6) submittals; and WHEREAS, after review and consideration of the ranked submittals, the Village Manager recommends selecting Kimley Horn and Associates, Inc. ("Consultant") for the ooA"; Services, whose qualifications are attached hereto as Exhibit and WHEREAS, the Village Council desires to select the Consultant for the Services; and WHEREAS, the Village Council finds that this Resolution is in the best interest and welfare of the citizens of the Village. NO\il, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED BY THE VILLAGE COUNCIL OF THE VILLAGE OF KEY BISCAYNE, FLORIDA AS FOLLOWS: Section 1. Recitals. Each of the above-stated recitals are hereby adopted, confirmed, and incorporated herein. Section 2. Selection. The Village Council hereby selects the Consultant for the Services for the Project. Section 3. Authorization. The Village Council hereby authorizes the Village Manager to negotiate arL agreement with Consultant for the Services for the Project. If an Page 1 of2 agreement cannot be reached, the Village Manager is authorized to negotiate an agreement with the next highest ranked firm(s), in order of ranking, until an agreement in the best interest of the Village is reached. -

BISCAYNE NATIONAL PARK the Florida Keys Begin with Soldier Key in the Northern Section of the Park and Continue to the South and West

CHAPTER TWO: BACKGROUND HISTORY GEOLOGY AND PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY OF BISCAYNE NATIONAL PARK The Florida Keys begin with Soldier Key in the northern section of the Park and continue to the south and west. The upper Florida Keys (from Soldier to Big Pine Key) are the remains of a shallow coral patch reef that thrived one hundred thousand or more years ago, during the Pleistocene epoch. The ocean level subsided during the following glacial period, exposing the coral to die in the air and sunlight. The coral was transformed into a stone often called coral rock, but more correctly termed Key Largo limestone. The other limestones of the Florida peninsula are related to the Key Largo; all are basically soft limestones, but with different bases. The nearby Miami oolitic limestone, for example, was formed by the precipitation of calcium carbonate from seawater into tiny oval particles (oolites),2 while farther north along the Florida east coast the coquina of the Anastasia formation was formed around the shells of Pleistocene sea creatures. When the first aboriginal peoples arrived in South Florida approximately 10,000 years ago, Biscayne Bay was a freshwater marsh or lake that extended from the rocky hills of the present- day keys to the ridge that forms the current Florida coast. The retreat of the glaciers brought about a gradual rise in global sea levels and resulted in the inundation of the basin by seawater some 4,000 years ago. Two thousand years later, the rising waters levelled off, leaving the Florida Keys, mainland, and Biscayne Bay with something similar to their current appearance.3 The keys change. -

May 29 2020 Seminole Tribune

Princess Ulele Tribe a big hit with Ozzy Osceola leaves returns in Tampa students in Rome OHS with good memories COMMUNITY v 5A EDUCATION v 1B SPORTS v 5B www.seminoletribune.org Free Volume XLIV • Number 5 May 29, 2020 Casinos Chief DiPetrillo remembered for nearly begin to 50 years of service to Broward, Tribe BY KEVIN JOHNSON reopen Senior Editor Donald DiPetrillo, who served the Seminole Tribe of Florida as its fire BY KEVIN JOHNSON chief since 2008 and had worked for fire Senior Editor departments in Broward County for nearly 50 years, died April 30 at Memorial Regional Hospital in Hollywood. He was 70. Emerson, Lake & Palmer wasn’t there to William Latchford, executive director greet customers, but their lyrics would have of public safety for the Seminole Tribe, been appropriate for the reopening of the fondly remembered Chief DiPetrillo for his Seminole Hard Rock Hotel & Casino Tampa. “Welcome back my friends to the show that never ends. We’re so glad you could attend; come inside, come inside.” The Tampa venue, like all in the Hard Rock/Seminole Gaming family, closed March 20 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Tampa’s doors remained closed until the evening of May 21 when the casino and hotel reopened with a bevy of new precautions aimed at keeping customers and staff safe. “Hard Rock and Seminole Gaming have made a tremendous commitment to sanitary protocols and a safety-first mentality for both guests and team members,” Jim Allen, CEO WPLG of Seminole Gaming and Chairman of Hard A Seminole Tribe ambulance carrying the casket of Seminole Fire Chief Donald DiPetrillo is saluted by the department during the chief’s funeral procession Rock International, said in a statement prior at Lauderdale Memorial Park in Fort Lauderdale.