Ellis & Associates, Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winning the Right Way Standards of Busin Ess Co Nduct

Standards of business conduct Winning the right way Standards of busin ess co nduct Table o cont nts 4 HP Values 4 Core Principles 4 Leader Attributes 6 A message from Dian Weisler 6 A message from David Deitchman 7 Using the HP Standards of Business Conduct 9 The Headline Test 9 Unsure about a decision or action? 10 Building trust 10 We make ethical decisions 10 We take action when aware of misconduct and do not retaliate 10 We cooperate with investigations 11 Respect 11 We honor human rights 11 We treat others with respect 11 We maintain a safe and secure work environment 11 We promote and provide a harassment-free work environment 11 We respect privacy and protect personal information Standards of bus iness co nduct 12 Uncompromising integrity 12 We use assets wisely 12 We maintain accurate business records 12 We avoid conft.icts of interest 13 We provide and accept gifts and entertainment only when appropriate 13 We do not bribe or accept kickbacks 13 We protect sensitive information 14 We comply with laws governing international trade 14 We do not trade on or disclose nonpublic material information 15 Passion for customers 15 We provide quality products and services 15 We market responsibly 15 We compete vigorously and fairly 15 We obtain business intelligence appropriately 16 Responsible citizenship 16 We are stewards of the environment 16 We engage with responsible business partners and suppliers 17 We communicate honestly with investors and the media 17 We exercise our rights in the political process 17 We support giving and volunteering in our communities 18 Winning the right way, every day 19 Contacting the Ethics and Compliance Office Standards of business co nduct Since Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard started our company many years ago, HP has been known not just for the products and services we offer, but also for the values we share. -

A Denial the Death of Kurt Cobain the Seattle

A DENIAL THE DEATH OF KURT COBAIN THE SEATTLE POLIECE DEPARTMENT’S SUBSTANDARD INVESTIGATION & THE REPROCUSSIONS TO JUSTICE by BREE DONOVAN A Capstone Submitted to The Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, The State University, New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Liberal Studies Under the direction of Dr. Joseph C. Schiavo and approved by _________________________________ Capstone Director _________________________________ Program Director Camden, New Jersey, December 2015 CAPSTONE ABSTRACT A Denial The Death of Kurt Cobain The Seattle Police Department’s Substandard Investigation & The Repercussions to Justice By: BREE DONOVAN Capstone Director: Dr. Joseph C. Schiavo Kurt Cobain (1967-1994) musician, artist songwriter, and founder of The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame band, Nirvana, was dubbed, “the voice of a generation”; a moniker he wore like his faded cardigan sweater, but with more than some distain. Cobain’s journey to the top of the Billboard charts was much more Dickensian than many of the generations of fans may realize. During his all too short life, Cobain struggled with physical illness, poverty, undiagnosed depression, a broken family, and the crippling isolation and loneliness brought on by drug addiction. Cobain may have shunned the idea of fame and fortune but like many struggling young musicians (who would become his peers) coming up in the blue collar, working class suburbs of Aberdeen and Tacoma Washington State, being ii on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine wasn’t a nightmare image. Cobain, with his unkempt blond hair, polarizing blue eyes, and fragile appearance is a modern-punk-rock Jesus; a model example of the modern-day hero. -

Hay Any Work for Cooper 1 ______

MARPRELATE TRACTS: HAY ANY WORK FOR COOPER 1 ________________________________________________________________________________ Hay Any Work For Cooper.1 Or a brief pistle directed by way of an hublication2 to the reverend bishops, counselling them if they will needs be barrelled up3 for fear of smelling in the nostrils of her Majesty and the state, that they would use the advice of reverend Martin for the providing of their cooper. Because the reverend T.C.4 (by which mystical5 letters is understood either the bouncing parson of East Meon,6 or Tom Cook's chaplain)7 hath showed himself in his late Admonition To The People Of England to be an unskilful and beceitful8 tub-trimmer.9 Wherein worthy Martin quits himself like a man, I warrant you, in the modest defence of his self and his learned pistles, and makes the Cooper's hoops10 to fly off and the bishops' tubs11 to leak out of all cry.12 Penned and compiled by Martin the metropolitan. Printed in Europe13 not far from some of the bouncing priests. 1 Cooper: A craftsman who makes and repairs wooden vessels formed of staves and hoops, as casks, buckets, tubs. (OED, p.421) The London street cry ‘Hay any work for cooper’ provided Martin with a pun on Thomas Cooper's surname, which Martin expands on in the next two paragraphs with references to hubs’, ‘barrelling up’, ‘tub-trimmer’, ‘hoops’, ‘leaking tubs’, etc. 2 Hub: The central solid part of a wheel; the nave. (OED, p.993) 3 A commodity commonly ‘barrelled-up’ in Elizabethan England was herring, which probably explains Martin's reference to ‘smelling in the nostrils of her Majesty and the state’. -

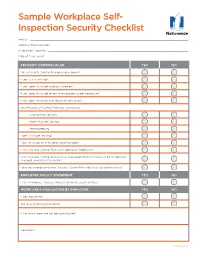

Sample Workplace Self- Inspection Security Checklist

Sample Workplace Self- Inspection Security Checklist Facility: ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� Address/Work Location: �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� Assessment Done By: ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� Date of Assessment: ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ SECURITY CONTROL PLAN YES NO Has a Security Control Plan been developed? If yes, is it in writing? If yes, does it include a policy statement? If yes, does it include review of employee incident exposure? If yes, does it include evaluation of work areas? Identification of Control Methods considered: Engineering Controls Work Practice Controls Recordkeeping Does it include training? Does it include an evacuation and floor plan? Is the Security Control Plan accessible to all employees? Is the Security Control Plan reviews and updated when a task has been added or changed, and at least annually? Have you coordinated your Security Control Plan with local law enforcement? EMPLOYER POLICY STATEMENT YES NO Is the Workplace Violence Policy statement clearly written? WORK AREA EVALUATION BY EMPLOYER YES NO If yes, how often? Are all areas being evaluated? If no, which areas are not being evaluated? Comments: Continued >> Loss Control Services Workplace Security Checklist CONTROL MEASURES -

Military Commander and the Law – 2019

THE MILITARY • 2019 COMMANDER AND THE THE LAW MILITARY THE MILITARY COMMANDER AND THE LAW TE G OCA ENE DV RA A L E ’S G S D C H U J O E O H L T U N E C IT R E D FO S R TATES AI The Military Commander and the Law is a publication of The Judge Advocate General’s School. This publication is used as a deskbook for instruction at various commander courses at Air University. It also serves as a helpful reference guide for commanders in the field, providing general guidance and helping commanders to clarify issues and identify potential problem areas. Disclaimer: As with any publication of secondary authority, this deskbook should not be used as the basis for action on specific cases. Primary authority, much of which is cited in this edition, should first be carefully reviewed. Finally, this deskbook does not serve as a substitute for advice from the staff judge advocate. Editorial Note: This edition was edited and published during the Secretary of the Air Force’s Air Force Directive Publication Reduction initiative. Therefore, many of the primary authorities cited in this edition may have been rescinded, consolidated, or superseded since publication. It is imperative that all authorities cited herein be first verified for currency on https://www.e-publishing.af.mil/. Readers with questions or comments concerning this publication should contact the editors of The Military Commander and the Law at the following address: The Judge Advocate General’s School 150 Chennault Circle (Bldg 694) Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama 36112-6418 Comm. -

Time to Listen: Hearing People on the Receiving End of International

TIME TO LISTEN Hearing People on the Receiving End of International Aid TIME TO LISTEN TO TIME “Time to Listen is both radical and practical. Refreshingly, the authors challenge the dominant delivery system approach to international assistance and its behav- TIME TO LISTEN iours, relationships, procedures and patterns of power. This leads to an insight- ful and practical agenda. All who are engaged with international assistance— whether as politician, policy-maker, offi cial, consultant, volunteer, technical expert, practitioner, analyst, activist or fi eld worker in aid agency, government, Hearing People foundation, NGO, social movement, academia, the private sector or elsewhere —should hear, take to heart, and act on the voices and ideas in this book. Igno- Hearing People on the Receiving Aid International of End on the Receiving End rance or lack of ideas of what to do can now never be an excuse.” - Dr. Robert Chambers, Institute of Development Studies of International Aid “The international aid system has failed to align its policies with the realities on the ground; this has led to a failure of development assistance in Afghanistan. Mary B. Anderson Time to Listen addresses these issues head-on by relaying valuable information from those affected in the fi eld...the voices represented here offer powerful in- Dayna Brown sight that cannot be ignored.” - Mohammad Ehsan Zia, Former Minister of the Afghanistan Ministry Isabella Jean of Rural Rehabilitation and Development “These voices tell us about an international aid system which is seriously mis- aligned with the way communities go about their business, to the point of being almost dysfunctional despite its good intentions. -

Techincal Memorandum 1 81

.c -...o ." CII Vl ... ..CII ~ Cl> ~c ::> o ~ I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I AIDS TO UNDERWATER SEARCHING C D PAYNE Technical Memorandum No. 1/81 I I I The views and conclusions expressed in this memorandum are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the policy of the Police Department. The contents of this document have been given a restricted circulation and are not to be reproduced in whole or in part without the written permission of the Home Office which should be sought from the Director, Police Scientific Development Branch. HOME OFFICE Police Scientific Development Branch Horseferry House Dean Ryle Street London SWIP 2AW I I I I CONTENTS I 1. INTRODUCTION 2. THE PROBLEM OF UNDERWATER SEARCHING 3. TRIJ'.LS 3.1 Depth sounders 3.2 Sonars 3.3 Thorn-EMI acoustic imager 3.4 The fluxgate gradiometer 4. CONCLUSION 5. REFERENCES 6. FIGURES CIRCULATION I I I I I I I I I ; . SUr-U"J\RY At the recent request of the Association of Chief Police Office r s Diving Committee, Police Scientific Development Br-ancl! has been examining the latest develDpments in depth sounders and short range sonars, and their applicabtlity to police diving operations. Some limited trials have taken place and these are described. 1. INTRODUC'rION Police Scientific Development Branch has been examining the possibility of producing aids for police divers carrying out underwater searches ever since 1970. At that time a contract was awarded to Birmingham University to investigate the problem and to produce a high resolution sonar capable of imaging objects on the bottom of inland waterways. -

Water Safety Code

CONTENTS Water Safety Code Contents 1 The Water Safety Code 2 Appendices 2 Guidance Notes 6 Appendix 1 2.1 Definitions 6 Coach/Participant Ratios 30 2.1.1 Safety Adviser 6 2.1.2 Medical Adviser 7 Appendix 2 Safety Audit Sheet - 2.2 Safety Plan 8 Clubs 31 2.3 Safety Audit 8 Appendix 3 Safety Audit Sheet - 2.4 Accident/Incident reporting 9 Events 34 2.5 Responsibilities 10 Appendix 4 2.5.1 Education 10 Incident Report Form 36 2.5.2 The Athlete/Participant 10 2.5.3 Steersmen/women and coxswains 11 Appendix 4a 2.5.4 The Coach 12 ARA Regatta/Head Medical Return 38 2.5.5 Launch Drivers 13 2.5.6 Trailer Drivers 14 Appendix 5 Navigation, Sounds 2.6 Equipment 15 and Signals 39 2.7 Safety at Regattas and other rowing/sculling events 16 Appendix 6 2.7.1 General 16 Safety Launch Drivers 2.7.2 Duty of Care 18 - Guidance Notes 40 2.7.3 Risk Assessment 19 2.8 Safety Aids 21 2.8.1 Lifejackets and buoyancy aids 21 2.9 Hypothermia 23 2.10 Resuscitation 25 2.11 Water borne diseases 28 Page 1 THE WATE R SAFETY CODE 1 The Water Safety Code 1.1 Every affiliated Club, School, College, Regatta and Head Race (hereafter reference will only be made to Club) shall have at all times a Safety Adviser whose duty it will be to understand and interpret the Guidance Notes and requirements of the Code, and ensure at all times its prominent display, observation and implementation. -

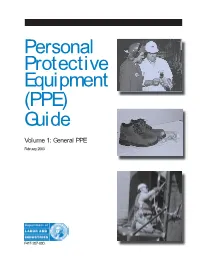

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Guide

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Guide Volume 1: General PPE February 2003 F417-207-000 This guide is designed to be used by supervisors, lead workers, managers, employers, and anyone responsible for the safety and health of employees. Employees are also encouraged to use information in this guide to analyze their own jobs, be aware of work place hazards, and take active responsibility for their own safety. Photos and graphic illustrations contained within this document were provided courtesy of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), Oregon OSHA, United States Coast Guard, EnviroWin Safety, Microsoft Clip Gallery (Online), and the Washington State Department of Labor and Industries. TABLE OF CONTENTS (If viewing this pdf document on the computer, you can place the cursor over the section headings below until a hand appears and then click. You can also use the Adobe Acrobat Navigation Pane to jump directly to the sections.) How To Use This Guide.......................................................................................... 4 A. Introduction.........................................................................................6 B. What you are required to do ..............................................................8 1. Do a Hazard Assessment for PPE and document it ........................................... 8 2. Select and provide appropriate PPE to your employees................................... 10 3. Provide training to your employees and document it ........................................ 11 -

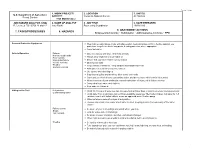

7. Tasks/Procedures 8. Hazards 9. Abatement

FS-6700-7 (11/99) 1. WORK PROJECT/ 2. LOCATION 3. UNIT(S) U.S. Department of Agriculture ACTIVITY Coconino National Forest All Districts Forest Service Trail Maintenance JOB HAZARD ANALYSIS (JHA) 4. NAME OF ANALYST 5. JOB TITLE 6. DATE PREPARED References-FSH 6709.11 and 12 Amy Racki Partnership Coordinator 10/28/2013 9. ABATEMENT ACTIONS 7. TASKS/PROCEDURES 8. HAZARDS Engineering Controls * Substitution * Administrative Controls * PPE Personal Protective Equipment Wear helmet, work gloves, boots with slip-resistant heels and soles with firm, flexible support, eye protection, long sleeve shirts, long pants, hearing protection where appropriate Carry first aid kit Vehicle Operation Fatigue Drive defensively and slow. Watch for animals Narrow, rough roads Always wear seatbelts and turn lights on Poor visibility Mechanical failure Ensure that you have reliable communication Vehicle Accients Obey speed limits Weather Keep vehicles maintained. Keep windows and windshield clean Animals on Road Anticipate careless actions by other drivers Use spotter when backing up Stay clear of gullies and trenches, drive slowly over rocks. Carry and use chock blocks, use parking brake, and do not leave vehicle while it is running Inform someone of your destination and estimated time of return, call in if plans change Carry extra food, water, and clothing Stop and rest if fatigued Hiking on the Trail Dehydration Drink 12-15 quarts of water per day, increase fluid on hotter days or during extremely strenuous activity Contaminated water Drink -

4 Water Safety Plans

4 Water safety plans he most effective means of consistently ensuring the safety of a drinking-water Tsupply is through the use of a comprehensive risk assessment and risk manage- ment approach that encompasses all steps in water supply from catchment to con- sumer. In these Guidelines, such approaches are termed water safety plans (WSPs). The WSP approach has been developed to organize and systematize a long history of management practices applied to drinking-water and to ensure the applicability of these practices to the management of drinking-water quality. It draws on many of the principles and concepts from other risk management approaches, in particular the multiple-barrier approach and HACCP (as used in the food industry). This chapter focuses on the principles of WSPs and is not a comprehensive guide to the application of these practices. Further information on how to develop a WSP is available in the supporting document Water Safety Plans (section 1.3). Some elements of a WSP will often be implemented as part of a drinking-water supplier’s usual practice or as part of benchmarked good practice without consolida- tion into a comprehensive WSP. This may include quality assurance systems (e.g., ISO 9001:2000). Existing good management practices provide a suitable platform for inte- grating WSP principles. However, existing practices may not include system-tailored hazard identification and risk assessment as a starting point for system management. WSPs can vary in complexity, as appropriate for the situation. In many cases, they will be quite simple, focusing on the key hazards identified for the specific system. -

Iain Sinclair and the Psychogeography of the Split City

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Iain Sinclair and the psychogeography of the split city https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40164/ Version: Full Version Citation: Downing, Henderson (2015) Iain Sinclair and the psychogeog- raphy of the split city. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email 1 IAIN SINCLAIR AND THE PSYCHOGEOGRAPHY OF THE SPLIT CITY Henderson Downing Birkbeck, University of London PhD 2015 2 I, Henderson Downing, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Abstract Iain Sinclair’s London is a labyrinthine city split by multiple forces deliriously replicated in the complexity and contradiction of his own hybrid texts. Sinclair played an integral role in the ‘psychogeographical turn’ of the 1990s, imaginatively mapping the secret histories and occulted alignments of urban space in a series of works that drift between the subject of topography and the topic of subjectivity. In the wake of Sinclair’s continued association with the spatial and textual practices from which such speculative theses derive, the trajectory of this variant psychogeography appears to swerve away from the revolutionary impulses of its initial formation within the radical milieu of the Lettrist International and Situationist International in 1950s Paris towards a more literary phenomenon. From this perspective, the return of psychogeography has been equated with a loss of political ambition within fin de millennium literature.