Iain Sinclair and the Psychogeography of the Split City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--History History 2016 Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945 Danielle K. Dodson University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.339 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dodson, Danielle K., "Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945" (2016). Theses and Dissertations--History. 40. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/history_etds/40 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--History by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Downloaded From: Usage Rights: Creative Commons: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Deriva- Tive Works 4.0

Read, Howard (2019) The role of drawing in the regeneration of urban spaces. Doctoral thesis (PhD), Manchester Metropolitan University. Downloaded from: https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/626054/ Usage rights: Creative Commons: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Deriva- tive Works 4.0 Please cite the published version https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk The role of drawing in the regeneration of urban spaces Howard Read PhD 2019 The role of drawing in the regeneration of urban spaces Howard Read A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy PAHC Manchester School of Art March 2019 1 Abstract: This PhD project critically analyses processes of urban regeneration using drawing as a core research method. The methodology applies a synergy between drawing practice and theoretical writing about urban spaces, regeneration and the city. The project uses the contested regeneration of the Elephant and Castle in south east London as its primary case study. The area has an extensive historical visual record of urban change and redevelopment since the nineteenth century. The thesis integrates current theories and debates on drawing with urban regeneration. It is partly an account of the drawing process, what I have witnessed and how I recorded it, and how this relates to the theoretical aspects of the research. I have interlinked the multi-themed purposes and motivations behind urban regeneration, visual planning and the London imaginary in the thesis. Many aspects of the stages of urban regeneration have been under-observed, and official visual representations by developers and the local council dominate the flow of public information and perception of changes taking place. -

London Office Policy Review 2012

London Office Policy Review 2012 Prepared for: Greater London Authority 1 By RAMIDUS CONSULTING LIMITED Date: September 2012 London Office Policy Review 2012 London Office Policy Review 2012 By Ramidus Consulting Limited with Roger Tym & Partners September 2012 Dedication During the preparation of this report one of the principal authors died very suddenly. David Chippendale had been involved in the LOPR since its inception, and has played a major part in laying sound foundations for what is now seen as the authoritative review of London office policy. David was a leading personality of the property research industry and will be hugely missed by many friends and colleagues. We dedicate LOPR 12 to David’s memory. Acknowledgements Ramidus Consulting Limited was appointed in February 2012 to undertake LOPR 12. The team comprised Rob Harris, David Chippendale, Ian Cundell and Sandra Jones. We have worked very closely with Dave Lawrence and Adala Leeson of Roger Tym & Partners, who have provided invaluable input to the forecasting and policy analysis. Martin Davis of DTZ and Theresa Keogh and Hannah Lakey of EGi have once again provided data, and we thank them for their assistance. Prepared for: Greater London Authority i By RAMIDUS CONSULTING LIMITED Date: September 2012 London Office Policy Review 2012 Contents Page Management summary v 1.0 Supply and demand in Central London 1 1.1 The Central London office market in context 1.2 Market and planning data in Central London 1.3 Central London availability and take-up overview 1.4 Central London -

Issues I — Ii — Iii — Iv the — Unlimited — Edition

THE — UNLIMITED EDITION ISSUES I — II III IV Many thanks to all our contributors This issue of The Unlimited Edition has for their hard work been printed locally by Aldgate Press, with recycled paper by local Published by supplier Paperback We Made That www.wemadethat.co.uk www.aldgatepress.co.uk www.paperback.coop Designed by Andrew Osman & Stephen Osman www.andrewosman.co.uk www.stephenosman.co.uk THE — UNLIMITED — EDITION ISSUE I — SURVEY — AUGUST 2011 2 THE — UNLIMITED — EDITION ISSUE I — SURVEY — AUGUST 2011 THE — UNLIMITED — EDITION ISSUE I — SURVEY — AUGUST 2011 3 is to record and explore the familiar, the transitory nature of the area for the High Street 2012 Historic Buildings Officer and to celebrate and speculate on the present day commuter. for Tower Hamlets Council, also gives possibilities that lie in its future. Expanding outwards from this critical us his personal perspective on some of In our first issue, ‘Survey’, we focus on highway, articles from Ruth Beale and the restoration works that form part the existing nature of the High Street. Clare Cumberlidge reveal the tight mesh of the wider heritage remit of the High Olympic Park Our contributors have been invited from of social, cultural, ethnic and economic Street 2012 initiative. Whitechapel Market a wide range of disciplines: they have fabric that surrounds the High Street in may hold new delights for you once you Holly Lewis, We Made That watched, read, analysed, photographed Aldgate and Wentworth Street. Such have imagined the stallholders as part of and illustrated the High Street to bring to hidden links and ties are further elaborated a life-sized ‘Happy Families’ card game, Stratford Welcome to Issue I of The Unlimited you a collection of articles as varied, by Esme Fieldhouse and Stephen Mackie, as Hattie Haseler has done, or considered Ω Ω Edition. -

The Avarice and Ambition of William Benson’, the Georgian Group Journal, Vol

Anna Eavis, ‘The avarice and ambition of William Benson’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XII, 2002, pp. 8–37 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2002 THE AVARICE AND AMBITION OF WILLIAM BENSON ANNA EAVIS n his own lifetime William Benson’s moment of probably motivated by his desire to build a neo- Ifame came in January , as the subject of an Palladian parliament house. anonymous pamphlet: That Benson had any direct impact on the spread of neo-Palladian ideas other than his patronage of I do therefore with much contrition bewail my making Campbell through the Board of Works is, however, of contracts with deceitfulness of heart … my pride, unlikely. Howard Colvin’s comprehensive and my arrogance, my avarice and my ambition have been my downfall .. excoriating account of Benson’s surveyorship shows only too clearly that his pre-occupations were To us, however, he is also famous for building a financial and self-motivated, rather than aesthetic. precociously neo-Palladian house in , as well He did not publish on architecture, neo-Palladian or as infamous for his corrupt, incompetent and otherwise and, with the exception of Wilbury, consequently brief tenure as Surveyor-General of the appears to have left no significant buildings, either in King’s Works, which ended in his dismissal for a private or official capacity. This absence of a context deception of King and Government. Wilbury, whose for Wilbury makes the house even more startling; it elevation was claimed to be both Jonesian and appears to spring from nowhere and, as far as designed by Benson, and whose plan was based on Benson’s architectural output is concerned, to lead that of the Villa Poiana, is notable for apparently nowhere. -

Social Studies of Science

Social Studies of Science http://sss.sagepub.com Mind the Gap: The London Underground Map and Users' Representations of Urban Space Janet Vertesi Social Studies of Science 2008; 38; 7 DOI: 10.1177/0306312707084153 The online version of this article can be found at: http://sss.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/38/1/7 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Social Studies of Science can be found at: Email Alerts: http://sss.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://sss.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav Citations http://sss.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/38/1/7 Downloaded from http://sss.sagepub.com at UNIV OF TEXAS AUSTIN on December 23, 2009 ABSTRACT This paper explores the effects of iconic, abstract representations of complex objects on our interactions with those objects through an ethnographic study of the use of the London Underground Map to tame and enframe the city of London. Official reports insist that the ‘Tube Map’s’ iconic status is due to its exemplary design principles or its utility for journey planning underground. This paper, however, presents results that suggest a different role for the familiar image: one of an essential visual technology that stands as an interface between the city and its user, presenting and structuring the points of access and possibilities for interaction within the urban space. The analysis explores the public understanding of an inscription in the world beyond the laboratory bench, the indexicality of the immutable mobile’s visual language, and the relationship between representing and intervening. -

Hawksmoor's Churches: Myth and Architecture in the Works of Iain Sinclair and Peter Ackroyd

Wenshan Review of Literature and Culture.Vol 5.2.June 2012.1-23. Hawksmoor's Churches: Myth and Architecture in the Works of Iain Sinclair and Peter Ackroyd Eva Yin-I Chen ABSTRACT The works of contemporary British writers Iain Sinclair and Peter Ackroyd demonstrate an intense preoccupation with the spatial symbols and ruins of London’s East End, which to them stand not just for the broken pieces of a vanishing past but also as symptoms of an underlying force of mythological and cultural significance, a force that collapses contemporary ideology and resists consecutive attempts at control and order. Of these, the Hawksmoor churches built by the architect Nickolas Hawksmoor after the 1666 London fire, some already demolished and others standing dark and brooding with looming spires and shadowy recesses, take on a particular preeminence. Both writers view the churches as forming an invisible geometry of lines of power in the cartography of the city, calling forth occult energies that point to the deeper, though half-erased and repressed truth of London. Sinclair’s early poetry collection Lud Heat first toys with this idea, and Ackroyd’s bestselling novel Hawksmoor popularizes it and enables it to reach a wider public. This paper investigates the spatial and mythological symbolism of the Hawksmoor churches as reflected in the works of the two writers, arguing that this recurrent spatial motif holds the key to understanding an important strand of contemporary British literature where architecture, textuality and London’s haunting past loom -

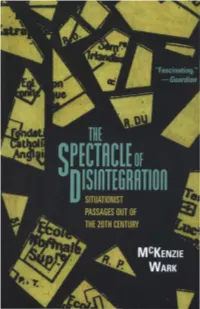

Spectacles of Disintegration

Unfold and flip to reveal a fold-out poster of the collaborative graphic essay combining text selected by McKenzie Wark with composition and drawings by Kevin C. Pyle. THE SPECTACLE OF DISINTEGRATION THE SPECTACLE OF DISINTEGRATION VERSO London • New York First published by Verso 2013 © McKenzie Wark 2013 All rights reserved The moral rights of the author have been asserted 1357 9108 642 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London Wl F OEG US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201 www.versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books ISBN-13: 978- 1-84467-957-7 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Typeset in Cochin by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall Printed in the US by Maple Vail Contents 1 Widening Gyres 2 The Critique of Everyday Life 13 3 Liberty Guiding the People 21 4 The Spectacle of Modern Life 33 5 Anarchies of Perception 41 6 The Revolution of Everyday Life 49 7 Detournement as Utopia 61 8 Charles Fourier's Queer Theory 71 9 The Ass Dreams of China Pop 85 10 Mao by Mao 95 11 The Occulted State 105 12 The Last Chance to Save Capitalism 115 13 Anti-Cinema 123 14 The Devil's Party 137 15 Guy Debord, His Art and Times 147 16 A Romany Detour 157 17 The Language of Discretion 165 1 8 Game of War 175 19 The Strategist 181 20 The Inhuman Comedy 189 AcknowleJgment.J 205 No te.J 207 Index 231 In memoryof: Mark Poster The rrwde of information Bernard Smith Place, taJteand tradition Adam Cullen The otherneJJ when itcomeJ It may not he what it loo/cJto lack totality. -

February/ March 2021

£1 Parish Magazine February/ March 2021 Chichester Road, Croydon www.stmatthew.org.uk Registered Charity No: 1132508 Services at St Matthew’s 1st Sunday 8.30 am Eucharist (Said) All other Sundays 10.00 am Parish Eucharist with Choir Tuesdays 9.00am Zoom Morning Prayer Meeting ID: 970 706 9858 Passcode: stmatts 1st Wednesday 10.00 am Holy Communion (Said) Please Note: Until further notice Services will be via our You Tube Channel and our website Baptisms, Weddings and Banns of Marriage By arrangement with the Vicar St Matthew’s Vision Sharing the Love of God The Vicar Writes… Dear Friend, “We’re all in this together” is an easy-to-say phrase that at one level may be true when applied to the crises we face, but at another level has a hollow ring when we consider the inequalities we are living with, as well as the random nature of the effect of Covid-19. Perhaps a more helpful way of looking at our current circumstances might be: “We are all in the same storm, but in different boats”. You may well have heard or seen this phrase already. I have certainly found it very helpful. Whatever it feels like at the moment in your particular “boat”, my prayer for you, as always, is that you will know the presence and the perfect peace of the God of love to be with you and in you, so that you will be able to cope with whatever storm you are in right now. The story of Jesus calming the storm (Matthew 8.23-27, Mark 4.35-41, Luke 8.22-25) is remarkable in a number of ways. -

Top of Page Interview Information--Different Title

Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California Berkeley Oral History Center University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Joey Terrill Joey Terrill: At the Forefront of Queer Chicano Art Interviews conducted by Todd Holmes in 2017 Interviews sponsored by the J. Paul Getty Trust Copyright © 2017 by J. Paul Getty Trust Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California Berkeley ii Since 1954 the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library, formerly the Regional Oral History Office, has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, -

The Situationist International on the 1960’S Radical Architecture: an Overview

ĠSTANBUL TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY THE SITUATIONIST INTERNATIONAL ON THE 1960’S RADICAL ARCHITECTURE: AN OVERVIEW M.Sc. Thesis by Hülya ERTAġ Department : Architecture Programme : Architectural Design JANUARY 2011 ĠSTANBUL TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY THE SITUATIONIST INTERNATIONAL ON THE 1960’S RADICAL ARCHITECTURE: AN OVERVIEW M.Sc. Thesis by Hülya ERTAġ 502071027 Date of submission : 20 December 2010 Date of defence examination: 28 January 2011 Supervisor (Chairman) : Assis. Prof. Dr. Ġpek AKPINAR (ĠTÜ) Members of the Examining Committee : Assoc. Prof. Dr. Arda ĠNCEOĞLU (ĠTÜ) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Bülent TANJU (YTÜ) JANUARY 2011 ĠSTANBUL TEKNĠK ÜNĠVERSĠTESĠ FEN BĠLĠMLERĠ ENSTĠTÜSÜ DURUMCU ENTERNASYONEL VE 1960’LARDAKĠ RADĠKAL MĠMARLIK YÜKSEK LĠSANS TEZĠ Hülya ERTAġ 502071027 Tezin Enstitüye Verildiği Tarih : 20 Aralık 2010 Tezin Savunulduğu Tarih : 28 Ocak 2011 Tez DanıĢmanı : Y. Doç. Dr. Ġpek AKPINAR (ĠTÜ) Diğer Jüri Üyeleri : Doç. Dr. Arda ĠNCEOĞLU (ĠTÜ) Doç. Dr. Bülent TANJU (YTÜ) OCAK 2011 FOREWORD I would like to express my deep appreciation and thanks to my advisor İpek Akpınar for all her support and inspiration. I thank all my friends, family and colleagues in XXI Magazine for their generous understanding. January 2011 Hülya ERTAŞ (Architect) v vi TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................... ix LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................... -

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk at the Turn of the Twenty-first Century Carlen Lavigne McGill University, Montréal Department of Art History and Communication Studies February 2008 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication Studies © Carlen Lavigne 2008 2 Abstract This study analyzes works of cyberpunk literature written between 1981 and 2005, and positions women’s cyberpunk as part of a larger cultural discussion of feminist issues. It traces the origins of the genre, reviews critical reactions, and subsequently outlines the ways in which women’s cyberpunk altered genre conventions in order to advance specifically feminist points of view. Novels are examined within their historical contexts; their content is compared to broader trends and controversies within contemporary feminism, and their themes are revealed to be visible reflections of feminist discourse at the end of the twentieth century. The study will ultimately make a case for the treatment of feminist cyberpunk as a unique vehicle for the examination of contemporary women’s issues, and for the analysis of feminist science fiction as a complex source of political ideas. Cette étude fait l’analyse d’ouvrages de littérature cyberpunk écrits entre 1981 et 2005, et situe la littérature féminine cyberpunk dans le contexte d’une discussion culturelle plus vaste des questions féministes. Elle établit les origines du genre, analyse les réactions culturelles et, par la suite, donne un aperçu des différentes manières dont la littérature féminine cyberpunk a transformé les usages du genre afin de promouvoir en particulier le point de vue féministe.