Sexual Selection Predicts Brain Structure in Dragon Lizards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gliding Dragons and Flying Squirrels: Diversifying Versus Stabilizing Selection on Morphology Following the Evolution of an Innovation

vol. 195, no. 2 the american naturalist february 2020 E-Article Gliding Dragons and Flying Squirrels: Diversifying versus Stabilizing Selection on Morphology following the Evolution of an Innovation Terry J. Ord,1,* Joan Garcia-Porta,1,† Marina Querejeta,2,‡ and David C. Collar3 1. Evolution and Ecology Research Centre and the School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Kensington, New South Wales 2052, Australia; 2. Institute of Evolutionary Biology (CSIC–Universitat Pompeu Fabra), Passeig Marítim de la Barceloneta, 37–49, Barcelona 08003, Spain; 3. Department of Organismal and Environmental Biology, Christopher Newport University, Newport News, Virginia 23606 Submitted August 1, 2018; Accepted July 16, 2019; Electronically published December 17, 2019 Online enhancements: supplemental material. Dryad data: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.t7g227h. fi abstract: Evolutionary innovations and ecological competition are eral de nitions of what represents an innovation have been factors often cited as drivers of adaptive diversification. Yet many offered (reviewed by Rabosky 2017), this classical descrip- innovations result in stabilizing rather than diversifying selection on tion arguably remains the most useful (Galis 2001; Stroud morphology, and morphological disparity among coexisting species and Losos 2016; Rabosky 2017). Hypothesized innovations can reflect competitive exclusion (species sorting) rather than sympat- have drawn considerable attention among ecologists and ric adaptive divergence (character displacement). We studied the in- evolutionary biologists because they can expand the range novation of gliding in dragons (Agamidae) and squirrels (Sciuridae) of ecological niches occupied within communities. In do- and its effect on subsequent body size diversification. We found that gliding either had no impact (squirrels) or resulted in strong stabilizing ing so, innovations are thought to be important engines of selection on body size (dragons). -

Level 1 Fauna Survey of the Gruyere Gold Project Borefields (Harewood 2016)

GOLD ROAD RESOURCES LIMITED GRUYERE PROJECT EPA REFERRAL SUPPORTING DOCUMENT APPENDIX 5: LEVEL 1 FAUNA SURVEY OF THE GRUYERE GOLD PROJECT BOREFIELDS (HAREWOOD 2016) Gruyere EPA Ref Support Doc Final Rev 1.docx Fauna Assessment (Level 1) Gruyere Borefield Project Gold Road Resources Limited January 2016 Version 3 On behalf of: Gold Road Resources Limited C/- Botanica Consulting PO Box 2027 BOULDER WA 6432 T: 08 9093 0024 F: 08 9093 1381 Prepared by: Greg Harewood Zoologist PO Box 755 BUNBURY WA 6231 M: 0402 141 197 T/F: (08) 9725 0982 E: [email protected] GRUYERE BOREFIELD PROJECT –– GOLD ROAD RESOURCES LTD – FAUNA ASSESSMENT (L1) – JAN 2016 – V3 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY 1. INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................1 2. SCOPE OF WORKS ...............................................................................................1 3. RELEVANT LEGISTALATION ................................................................................2 4. METHODS...............................................................................................................3 4.1 POTENTIAL VETEBRATE FAUNA INVENTORY - DESKTOP SURVEY ............. 3 4.1.1 Database Searches.......................................................................................3 4.1.2 Previous Fauna Surveys in the Area ............................................................3 4.1.3 Existing Publications .....................................................................................5 4.1.4 Fauna -

Management of the Terrestrial Small Mammal and Lizard Communities in the Dune System Of

Management of the terrestrial small mammal and lizard communities in the dune system of Sturt National Park, Australia: Historic and contemporary effects of pastoralism and fox predation Ulrike Sabine Klöcker (Dipl. – Biol., Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms Universität Bonn, Germany) Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences The University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia 2009 Abstract This thesis addressed three issues related to the management and conservation of small terrestrial vertebrates in the arid zone. The study site was an amalgamation of pastoral properties forming the now protected area of Sturt National Park in far-western New South Wales, Australia. Thus firstly, it assessed recovery from disturbance accrued through more than a century of Sheep grazing. Vegetation parameters, Fox, Cat and Rabbit abundance, and the small vertebrate communities were compared, with distance to watering points used as a surrogate for grazing intensity. Secondly, the impacts of small-scale but intensive combined Fox and Rabbit control on small vertebrates were investigated. Thirdly, the ecology of the rare Dusky Hopping Mouse (Notomys fuscus) was used as an exemplar to illustrate and discuss some of the complexities related to the conservation of small terrestrial vertebrates, with a particular focus on desert rodents. Thirty-five years after the removal of livestock and the closure of watering points, areas that were historically heavily disturbed are now nearly indistinguishable from nearby relatively undisturbed areas, despite uncontrolled native herbivore (kangaroo) abundance. Rainfall patterns, rather than grazing history, were responsible for the observed variation between individual sites and may overlay potential residual grazing effects. -

Fowlers Gap Biodiversity Checklist Reptiles

Fowlers Gap Biodiversity Checklist ow if there are so many lizards then they should make tasty N meals for someone. Many of the lizard-eaters come from their Reptiles own kind, especially the snake-like legless lizards and the snakes themselves. The former are completely harmless to people but the latter should be left alone and assumed to be venomous. Even so it odern reptiles are at the most diverse in the tropics and the is quite safe to watch a snake from a distance but some like the Md rylands of the world. The Australian arid zone has some of the Mulga Snake can be curious and this could get a little most diverse reptile communities found anywhere. In and around a disconcerting! single tussock of spinifex in the western deserts you could find 18 species of lizards. Fowlers Gap does not have any spinifex but even he most common lizards that you will encounter are the large so you do not have to go far to see reptiles in the warmer weather. Tand ubiquitous Shingleback and Central Bearded Dragon. The diversity here is as astonishing as anywhere. Imagine finding six They both have a tendency to use roads for passage, warming up or species of geckos ranging from 50-85 mm long, all within the same for display. So please slow your vehicle down and then take evasive genus. Or think about a similar diversity of striped skinks from 45-75 action to spare them from becoming a road casualty. The mm long! How do all these lizards make a living in such a dry and Shingleback is often seen alone but actually is monogamous and seemingly unproductive landscape? pairs for life. -

Habitat Types

Habitat Types The following section features ten predominant habitat types on the West Coast of the Eyre Peninsula, South Australia. It provides a description of each habitat type and the native plant and fauna species that commonly occur there. The fauna species lists in this section are not limited to the species included in this publication and include other coastal fauna species. Fauna species included in this publication are printed in bold. Information is also provided on specific threats and reference sites for each habitat type. The habitat types presented are generally either characteristic of high-energy exposed coastline or low-energy sheltered coastline. Open sandy beaches, non-vegetated dunefields, coastal cliffs and cliff tops are all typically found along high energy, exposed coastline, while mangroves, sand flats and saltmarsh/samphire are characteristic of low energy, sheltered coastline. Habitat Types Coastal Dune Shrublands NATURAL DISTRIBUTION shrublands of larger vegetation occur on more stable dunes and Found throughout the coastal environment, from low beachfront cliff-top dunes with deep stable sand. Most large dune shrublands locations to elevated clifftops, wherever sand can accumulate. will be composed of a mosaic of transitional vegetation patches ranging from bare sand to dense shrub cover. DESCRIPTION This habitat type is associated with sandy coastal dunes occurring The understory generally consists of moderate to high diversity of along exposed and sometimes more sheltered coastline. Dunes are low shrubs, sedges and groundcovers. Understory diversity is often created by the deposition of dry sand particles from the beach by driven by the position and aspect of the dune slope. -

Anolis Equestris) Should Be Removed When Face of a Watch

VOLUME 15, NUMBER 4 DECEMBER 2008 ONSERVATION AUANATURAL ISTORY AND USBANDRY OF EPTILES IC G, N H , H R International Reptile Conservation Foundation www.IRCF.org Central Netted Dragons (Ctenophorus nuchalis) from Australia are popular in captivity due to their striking appearance and great temperament. See article on p. 226. Known variously as Peters’ Forest Dragon, Doria’s Anglehead Lizard, or Abbott’s Anglehead Lizard (depending on subspecies), Gonocephalus doriae is known from southern Thailand, western Malaysia, and Indonesia west of Wallace’s Line SHANNON PLUMMER (a biogeographic division between islands associated with Asia and those with plants and animals more closely related to those on Australia). They live in remaining forested areas to elevations of 1,600 m (4,800 ft), where they spend most of their time high in trees near streams, either clinging to vertical trunks or sitting on the ends of thin branches. Their conservation status has not been assessed. MICHAEL KERN KENNETH L. KRYSKO KRISTA MOUGEY Newly hatched Texas Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma cornutum) on the Invasive Knight Anoles (Anolis equestris) should be removed when face of a watch. See article on p. 204. encountered in the wild. See article on p. 212. MARK DE SILVA Grenada Treeboas (Corallus grenadensis) remain abundant on many of the Grenadine Islands despite the fact that virtually all forested portions of the islands were cleared for agriculture during colonial times. This individual is from Mayreau. See article on p. 198. WIKIPEDIA.ORG JOSHUA M. KAPFER Of the snakes that occur in the upper midwestern United States, Populations of the Caspian Seal (Pusa caspica) have declined by 90% JOHN BINNS Bullsnakes (Pituophis catenifer sayi) are arguably the most impressive in in the last 100 years due to unsustainable hunting and habitat degra- Green Iguanas (Iguana iguana) are frequently edificarian on Grand Cayman. -

A Molecular Phylogenetic Study of Ecological Diversification in the Australian Lizard Genus Ctenophorus

JEZ Mde 2035 JOURNAL OF EXPERIMENTAL ZOOLOGY (MOL DEV EVOL) 291:339–353 (2001) A Molecular Phylogenetic Study of Ecological Diversification in the Australian Lizard Genus Ctenophorus JANE MELVILLE,* JAMES A. SCHULTE II, AND ALLAN LARSON Department of Biology, Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri 63130 ABSTRACT We present phylogenetic analyses of the lizard genus Ctenophorus using 1,639 aligned positions of mitochondrial DNA sequences containing 799 parsimony-informative charac- ters for samples of 22 species of Ctenophorus and 12 additional Australian agamid genera. Se- quences from three protein-coding genes (ND1, ND2, and COI) and eight intervening tRNA genes are examined using both parsimony and maximum-likelihood analyses. Species of Ctenophorus form a monophyletic group with Rankinia adelaidensis, which we suggest placing in Ctenophorus. Ecological differentiation among species of Ctenophorus is most evident in the kinds of habitats used for shelter. Phylogenetic analyses suggest that the ancestral condition is to use burrows for shelter, and that habits of sheltering in rocks and shrubs/hummock grasses represent separately derived conditions. Ctenophorus appears to have undergone extensive cladogenesis approximately 10–12 million years ago, with all three major ecological modes being established at that time. J. Exp. Zool. (Mol. Dev. Evol.) 291:339–353, 2001. © 2001 Wiley-Liss, Inc. The agamid lizard genus Ctenophorus provides ecological categories based on whether species abundant opportunity for a molecular phylogenetic shelter in rocks, burrows, or vegetation. Eight spe- study of speciation and ecological diversification. cies of Ctenophorus are associated with rocks: C. Agamid lizards show a marked radiation in Aus- caudicinctus, C. decresii, C. fionni, C. -

Journal of the Vict Orian Herpet Ological Society

POST PRINT APPROVED PP344786-0009 MONITOR - Journal of The Victorian Herpetological Society 11 (2) March,2001 JOURNAL OF THE VICTORIAN HERPETOLOGICAL SOCIETY HERPETOLOGICAL JOURNAL OF THE VICTORIAN MONITORMONITORMONITORVOL. 11 No. 2 March, 2001 Aust $10.00 1. MONITOR - Journal of The Victorian Herpetological Society 11 (2) March,2001 Published by: The Victorian Herpetological Society Inc Back issues of MONITOR are available for $12 per issue, (Except Vol 10 (2/3) $20) Price includes postage. Send cheque or Money order to: The Victorian Herpetological Society inc. PO Box 523, Somerville, 3912 Victoria. Available volumes 11 (1), 10 (1), 10(2/3), 9 (1), 9 ( 2), 8 (1), 8 (2), 8(3), 7 (1), 7 (2), 7 (3), 6 (1), 6 (2), 6 (3) 2. MONITOR - Journal of The Victorian Herpetological Society 11 (2) March,2001 Journal of the Victorian Herpetological Society Monitor Vol 11 No. 2 March, 2001 Monitor TABLE OF CONTENTS ISSN 1440-6241 My Say ... 4 - 5 VHS Committee President: Simon Watharow Mountain Dragons (Tympanocryptis Secretary: Peter Mantell diemensis) of Victoria: A Complex Issue. ... Treasurer: Steven Comber by Nick Clemann 6 - 8 Executive: Doug Wintle Executive: Scott Eipper A Field Trip to Flinders Island, Tasmania with a Dash of Chappell Island Please. ... Editor/Producer Simon Watharow by Simon Watharow 9 - 16 Asst Editors Ray Hoser, Peter Mantell, Steven Comber, Scott Eipper, Brian Barnett and Doug Locating the Southern Bell Frog ... Just Wintle Add Water. ... by Mike Swan 17 - 18. Production assistants Ray Hoser, Angela Reid and Simon Beatty. Observations of Herpetofauna on a Field Trip in Eastern New South Wales .. -

Nanya Station, Western New South Wales Vegetation, Flora and Fauna

NANYA STATION, WESTERN NEW SOUTH WALES VEGETATION, FLORA AND FAUNA Prepared by Martin E. Westbrooke, Centre for Environmental Management, University of Ballarat Nanya Station, owned and managed by the University of Ballarat was purchased with assistance from the Department of Environment and Heritage. Ongoing management is supported by the Lower Murray Darling Catchment Management Authority FOREWORD 1 FOREWORD This booklet has been prepared as an introduction for visitors to Nanya. Nanya is managed for conservation, research and teaching and affords protection to highly significant environments including two endangered communities and seventeen endangered or vulnerable species. On your visit, please respect these values. NANYA STATION Nanya Station is located in the Scotia country of far western New South Wales and consists of the Nanya Western Lands Pastoral Lease 3281 – Perpetual Leasehold Lot 1244 in Deposited Plan 762778, Parish of Winnebaga, County of Tara. Nanya Homestead complex 2 BACKGROUND The Scotia region has one of the shortest stock grazing histories of western NSW. Along with five other properties, Nanya was created as a pastoral lease in 1927. Previously the area was part of the large Lake Victoria lease and stock grazing occurred only in wet years (Withers 1989). The original lease was taken up by Gordon Cummings in 1927. He first dug a dam near the southeast corner of the property. A larger ground tank and homestead at the site of the present complex was later established. An area around the homestead was cleared and cropped to provide feed for the horses used in digging the earth tanks. The ruins of the original building are located between the shearing shed and Homestead Tank. -

Vertebrate Fauna Assessment

A LEVEL 1 VERTEBRATE FAUNA ASSESSMENT OF THE PROPOSED FORTESCUE RIVER GAS PIPELINE, WESTERN AUSTRALIA Prepared for: DDG & Mattiske Consulting Pty Ltd Prepared by: Ninox Wildlife Consulting December 2013 i Solomon Hub to CS 1 Gas Pipeline – Level 1 Vertebrate Fauna Assessment Table of Contents Page 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................ 1 2 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... 3 3 STUDY OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................................................... 3 4 NOMENCLATURE, TAXONOMY AND DISTRIBUTION PATTERNS ........................................... 5 5 METHODS .................................................................................................................................................. 5 5.1 PHASE 1 .............................................................................................................................................. 5 5.2 PHASE 2 .............................................................................................................................................. 5 5.3 STUDY TEAM ...................................................................................................................................... 6 5.4 STUDY LIMITATIONS ......................................................................................................................... -

A LIST of the VERTEBRATES of SOUTH AUSTRALIA

A LIST of the VERTEBRATES of SOUTH AUSTRALIA updates. for Edition 4th Editors See A.C. Robinson K.D. Casperson Biological Survey and Research Heritage and Biodiversity Division Department for Environment and Heritage, South Australia M.N. Hutchinson South Australian Museum Department of Transport, Urban Planning and the Arts, South Australia 2000 i EDITORS A.C. Robinson & K.D. Casperson, Biological Survey and Research, Biological Survey and Research, Heritage and Biodiversity Division, Department for Environment and Heritage. G.P.O. Box 1047, Adelaide, SA, 5001 M.N. Hutchinson, Curator of Reptiles and Amphibians South Australian Museum, Department of Transport, Urban Planning and the Arts. GPO Box 234, Adelaide, SA 5001updates. for CARTOGRAPHY AND DESIGN Biological Survey & Research, Heritage and Biodiversity Division, Department for Environment and Heritage Edition Department for Environment and Heritage 2000 4thISBN 0 7308 5890 1 First Edition (edited by H.J. Aslin) published 1985 Second Edition (edited by C.H.S. Watts) published 1990 Third Edition (edited bySee A.C. Robinson, M.N. Hutchinson, and K.D. Casperson) published 2000 Cover Photograph: Clockwise:- Western Pygmy Possum, Cercartetus concinnus (Photo A. Robinson), Smooth Knob-tailed Gecko, Nephrurus levis (Photo A. Robinson), Painted Frog, Neobatrachus pictus (Photo A. Robinson), Desert Goby, Chlamydogobius eremius (Photo N. Armstrong),Osprey, Pandion haliaetus (Photo A. Robinson) ii _______________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS -

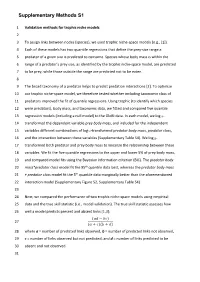

Supplementary Methods S1

1 Validation methods for trophic niche models 2 3 To assign links between nodes (species), we used trophic niche-space models (e.g., [1]). 4 Each of these models has two quantile regressions that define the prey-size range a 5 predator of a given size is predicted to consume. Species whose body mass is within the 6 range of a predator’s prey size, as identified by the trophic niche-space model, are predicted 7 to be prey, while those outside the range are predicted not to be eaten. 8 9 The broad taxonomy of a predator helps to predict predation interactions [2]. To optimize 10 our trophic niche-space model, we therefore tested whether including taxonomic class of 11 predators improved the fit of quantile regressions. Using trophic (to identify which species 12 were predators), body mass, and taxonomic data, we fitted and compared five quantile 13 regression models (including a null model) to the GloBI data. In each model, we log10- 14 transformed the dependent variable prey body mass, and included for the independent 15 variables different combinations of log10-transformed predator body mass, predator class, 16 and the interaction between these variables (Supplementary Table S4). We log10- 17 transformed both predator and prey body mass to linearize the relationship between these 18 variables. We fit the five quantile regressions to the upper and lower 5% of prey body mass, 19 and compared model fits using the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). The predator body 20 mass*predator class model fit the 95th quantile data best, whereas the predator body mass 21 + predator class model fit the 5th quantile data marginally better than the aforementioned 22 interaction model (Supplementary Figure S2, Supplementary Table S4).