Management of the Terrestrial Small Mammal and Lizard Communities in the Dune System Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lake Pinaroo Ramsar Site

Ecological character description: Lake Pinaroo Ramsar site Ecological character description: Lake Pinaroo Ramsar site Disclaimer The Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW (DECC) has compiled the Ecological character description: Lake Pinaroo Ramsar site in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. DECC does not accept responsibility for any inaccurate or incomplete information supplied by third parties. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. Readers should seek appropriate advice about the suitability of the information to their needs. © State of New South Wales and Department of Environment and Climate Change DECC is pleased to allow the reproduction of material from this publication on the condition that the source, publisher and authorship are appropriately acknowledged. Published by: Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW 59–61 Goulburn Street, Sydney PO Box A290, Sydney South 1232 Phone: 131555 (NSW only – publications and information requests) (02) 9995 5000 (switchboard) Fax: (02) 9995 5999 TTY: (02) 9211 4723 Email: [email protected] Website: www.environment.nsw.gov.au DECC 2008/275 ISBN 978 1 74122 839 7 June 2008 Printed on environmentally sustainable paper Cover photos Inset upper: Lake Pinaroo in flood, 1976 (DECC) Aerial: Lake Pinaroo in flood, March 1976 (DECC) Inset lower left: Blue-billed duck (R. Kingsford) Inset lower middle: Red-necked avocet (C. Herbert) Inset lower right: Red-capped plover (C. Herbert) Summary An ecological character description has been defined as ‘the combination of the ecosystem components, processes, benefits and services that characterise a wetland at a given point in time’. -

Gliding Dragons and Flying Squirrels: Diversifying Versus Stabilizing Selection on Morphology Following the Evolution of an Innovation

vol. 195, no. 2 the american naturalist february 2020 E-Article Gliding Dragons and Flying Squirrels: Diversifying versus Stabilizing Selection on Morphology following the Evolution of an Innovation Terry J. Ord,1,* Joan Garcia-Porta,1,† Marina Querejeta,2,‡ and David C. Collar3 1. Evolution and Ecology Research Centre and the School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Kensington, New South Wales 2052, Australia; 2. Institute of Evolutionary Biology (CSIC–Universitat Pompeu Fabra), Passeig Marítim de la Barceloneta, 37–49, Barcelona 08003, Spain; 3. Department of Organismal and Environmental Biology, Christopher Newport University, Newport News, Virginia 23606 Submitted August 1, 2018; Accepted July 16, 2019; Electronically published December 17, 2019 Online enhancements: supplemental material. Dryad data: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.t7g227h. fi abstract: Evolutionary innovations and ecological competition are eral de nitions of what represents an innovation have been factors often cited as drivers of adaptive diversification. Yet many offered (reviewed by Rabosky 2017), this classical descrip- innovations result in stabilizing rather than diversifying selection on tion arguably remains the most useful (Galis 2001; Stroud morphology, and morphological disparity among coexisting species and Losos 2016; Rabosky 2017). Hypothesized innovations can reflect competitive exclusion (species sorting) rather than sympat- have drawn considerable attention among ecologists and ric adaptive divergence (character displacement). We studied the in- evolutionary biologists because they can expand the range novation of gliding in dragons (Agamidae) and squirrels (Sciuridae) of ecological niches occupied within communities. In do- and its effect on subsequent body size diversification. We found that gliding either had no impact (squirrels) or resulted in strong stabilizing ing so, innovations are thought to be important engines of selection on body size (dragons). -

Dusky Hopping Mouse

Threatened Species of the Northern Territory DUSKY HOPPING-MOUSE Notomys fuscus Conservation status Australia: Vulnerable Northern Territory: Endangered Photo: P. Canty Description as Ooldea in South Australia and east to the Victoria/New South Wales borders. The dusky hopping-mouse is characterized by its strong incisor teeth, long tail, large ears, The species has not been recorded in the dark eyes, and extremely lengthened and Northern Territory since 1939 when it was narrow hind feet, which have only four pads collected in sand dunes on Maryvale Station on the sole. The head-body length is 91-177 and on Andado Station. An earlier record is mm, tail length is 125-225 mm, and body from Charlotte Waters. weight is about 20-50 g. Coloration of the Conservation reserves where reported: upper parts varies from pale sandy brown to None. yellowish brown to ashy brown or greyish. The underparts of dusky hopping-mice are white. The fur is fine, close and soft. Long hairs near the tip of the tail give the effect of a brush. The dusky hopping-mouse has a well- developed glandular area on the underside of its neck or chest. Females have four nipples. Distribution The current distribution of the dusky hopping-mouse appears to be restricted to the eastern Lake Eyre Basin within the Known locations of the dusky hopping-mouse Simpson-Strzelecki Dunefields bioregion in (ο = pre 1970). South Australia and Queensland. An intensive survey in the 1990s located populations at Ecology eight locations in the Strzelecki Desert and adjacent Cobbler Sandhills (South Australia) The dusky hopping-mouse occupies a variety and in south-west Queensland (Moseby et al. -

Calaby References

Abbott, I.J. (1974). Natural history of Curtis Island, Bass Strait. 5. Birds, with some notes on mammal trapping. Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 107: 171–74. General; Rodents; Abbott, I. (1978). Seabird islands No. 56 Michaelmas Island, King George Sound, Western Australia. Corella 2: 26–27. (Records rabbit and Rattus fuscipes). General; Rodents; Lagomorphs; Abbott, I. (1981). Seabird Islands No. 106 Mondrain Island, Archipelago of the Recherche, Western Australia. Corella 5: 60–61. (Records bush-rat and rock-wallaby). General; Rodents; Abbott, I. and Watson, J.R. (1978). The soils, flora, vegetation and vertebrate fauna of Chatham Island, Western Australia. Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia 60: 65–70. (Only mammal is Rattus fuscipes). General; Rodents; Adams, D.B. (1980). Motivational systems of agonistic behaviour in muroid rodents: a comparative review and neural model. Aggressive Behavior 6: 295–346. Rodents; Ahern, L.D., Brown, P.R., Robertson, P. and Seebeck, J.H. (1985). Application of a taxon priority system to some Victorian vertebrate fauna. Fisheries and Wildlife Service, Victoria, Arthur Rylah Institute of Environmental Research Technical Report No. 32: 1–48. General; Marsupials; Bats; Rodents; Whales; Land Carnivores; Aitken, P. (1968). Observations on Notomys fuscus (Wood Jones) (Muridae-Pseudomyinae) with notes on a new synonym. South Australian Naturalist 43: 37–45. Rodents; Aitken, P.F. (1969). The mammals of the Flinders Ranges. Pp. 255–356 in Corbett, D.W.P. (ed.) The natural history of the Flinders Ranges. Libraries Board of South Australia : Adelaide. (Gives descriptions and notes on the echidna, marsupials, murids, and bats recorded for the Flinders Ranges; also deals with the introduced mammals, including the dingo). -

Level 1 Fauna Survey of the Gruyere Gold Project Borefields (Harewood 2016)

GOLD ROAD RESOURCES LIMITED GRUYERE PROJECT EPA REFERRAL SUPPORTING DOCUMENT APPENDIX 5: LEVEL 1 FAUNA SURVEY OF THE GRUYERE GOLD PROJECT BOREFIELDS (HAREWOOD 2016) Gruyere EPA Ref Support Doc Final Rev 1.docx Fauna Assessment (Level 1) Gruyere Borefield Project Gold Road Resources Limited January 2016 Version 3 On behalf of: Gold Road Resources Limited C/- Botanica Consulting PO Box 2027 BOULDER WA 6432 T: 08 9093 0024 F: 08 9093 1381 Prepared by: Greg Harewood Zoologist PO Box 755 BUNBURY WA 6231 M: 0402 141 197 T/F: (08) 9725 0982 E: [email protected] GRUYERE BOREFIELD PROJECT –– GOLD ROAD RESOURCES LTD – FAUNA ASSESSMENT (L1) – JAN 2016 – V3 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY 1. INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................1 2. SCOPE OF WORKS ...............................................................................................1 3. RELEVANT LEGISTALATION ................................................................................2 4. METHODS...............................................................................................................3 4.1 POTENTIAL VETEBRATE FAUNA INVENTORY - DESKTOP SURVEY ............. 3 4.1.1 Database Searches.......................................................................................3 4.1.2 Previous Fauna Surveys in the Area ............................................................3 4.1.3 Existing Publications .....................................................................................5 4.1.4 Fauna -

Quaternary Murid Rodents of Timor Part I: New Material of Coryphomys Buehleri Schaub, 1937, and Description of a Second Species of the Genus

QUATERNARY MURID RODENTS OF TIMOR PART I: NEW MATERIAL OF CORYPHOMYS BUEHLERI SCHAUB, 1937, AND DESCRIPTION OF A SECOND SPECIES OF THE GENUS K. P. APLIN Australian National Wildlife Collection, CSIRO Division of Sustainable Ecosystems, Canberra and Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Mammalogy) American Museum of Natural History ([email protected]) K. M. HELGEN Department of Vertebrate Zoology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution, Washington and Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Mammalogy) American Museum of Natural History ([email protected]) BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY Number 341, 80 pp., 21 figures, 4 tables Issued July 21, 2010 Copyright E American Museum of Natural History 2010 ISSN 0003-0090 CONTENTS Abstract.......................................................... 3 Introduction . ...................................................... 3 The environmental context ........................................... 5 Materialsandmethods.............................................. 7 Systematics....................................................... 11 Coryphomys Schaub, 1937 ........................................... 11 Coryphomys buehleri Schaub, 1937 . ................................... 12 Extended description of Coryphomys buehleri............................ 12 Coryphomys musseri, sp.nov.......................................... 25 Description.................................................... 26 Coryphomys, sp.indet.............................................. 34 Discussion . .................................................... -

Natural History of the Eutheria

FAUNA of AUSTRALIA 35. NATURAL HISTORY OF THE EUTHERIA P. J. JARMAN, A. K. LEE & L. S. HALL (with thanks for help to J.H. Calaby, G.M. McKay & M.M. Bryden) 1 35. NATURAL HISTORY OF THE EUTHERIA 2 35. NATURAL HISTORY OF THE EUTHERIA INTRODUCTION Unlike the Australian metatherian species which are all indigenous, terrestrial and non-flying, the eutherians now found in the continent are a mixture of indigenous and exotic species. Among the latter are some intentionally and some accidentally introduced species, and marine as well as terrestrial and flying as well as non-flying species are abundantly represented. All the habitats occupied by metatherians also are occupied by eutherians. Eutherians more than cover the metatherian weight range of 5 g–100 kg, but the largest terrestrial eutherians (which are introduced species) are an order of magnitude heavier than the largest extant metatherians. Before the arrival of dingoes 4000 years ago, however, none of the indigenous fully terrestrial eutherians weighed more than a kilogram, while most of the exotic species weigh more than that. The eutherians now represented in Australia are very diverse. They fall into major suites of species: Muridae; Chiroptera; marine mammals (whales, seals and dugong); introduced carnivores (Canidae and Felidae); introduced Leporidae (hares and rabbits); and introduced ungulates (Perissodactyla and Artiodactyla). In this chapter an attempt is made to compare and contrast the main features of the natural histories of these suites of species and, where appropriate, to comment on their resemblance to or difference from the metatherians. NATURAL HISTORY Ecology Diet. The native rodents are predominantly omnivorous. -

LESSER STICK-NEST RAT Leporillus Apicalis

Threatened Species of the Northern Territory LESSER STICK-NEST RAT Leporillus apicalis Conservation status Australia: Extinct Northern Territory: Extinct (J Gould © Museum Victoria) Description The lesser stick-nest rat was a moderately sized native rodent (body mass 60 g) that differed from its larger relative, the greater stick-nest rat, by the narrow brush of white hairs near the tip of its tail. Distribution The last specimen of the lesser stick- nest rat was captured near Mt Crombie, south west of Known locations of the lesser stick-nest rat the present Amata settlement, South Australia ο = pre 1970 in 1933. However in the nineteenth century it occupied a broad swath of desert and semi- Ecology desert land stretching from the Riverina in New South Wales through most of inland The biology of the lesser sticknest rat is South Australia and into the Gibson Desert, poorly known. Its most notable feature was reaching the West Australian coast in the its construction of nests of sticks, sometimes Gascoyne region. Examination of middens of in the open, but often in caves and rock this species is providing significant new overhangs. information on environmental and climatic Conservation assessment change in central Australia over a 2500-year time frame. The lesser stick-nest rat is presumed to have Conservation reserves where reported: become extinct in the NT by the 1940s, None (however it formerly occurred in areas following a broad-scale decline extending that are now included within Uluru Kata-Tjuta over at least the previous 30 years (Finlayson National Park, Arltunga Historical Reserve, 1961; Burbidge et al. -

Ba3444 MAMMAL BOOKLET FINAL.Indd

Intot Obliv i The disappearing native mammals of northern Australia Compiled by James Fitzsimons Sarah Legge Barry Traill John Woinarski Into Oblivion? The disappearing native mammals of northern Australia 1 SUMMARY Since European settlement, the deepest loss of Australian biodiversity has been the spate of extinctions of endemic mammals. Historically, these losses occurred mostly in inland and in temperate parts of the country, and largely between 1890 and 1950. A new wave of extinctions is now threatening Australian mammals, this time in northern Australia. Many mammal species are in sharp decline across the north, even in extensive natural areas managed primarily for conservation. The main evidence of this decline comes consistently from two contrasting sources: robust scientifi c monitoring programs and more broad-scale Indigenous knowledge. The main drivers of the mammal decline in northern Australia include inappropriate fi re regimes (too much fi re) and predation by feral cats. Cane Toads are also implicated, particularly to the recent catastrophic decline of the Northern Quoll. Furthermore, some impacts are due to vegetation changes associated with the pastoral industry. Disease could also be a factor, but to date there is little evidence for or against it. Based on current trends, many native mammals will become extinct in northern Australia in the next 10-20 years, and even the largest and most iconic national parks in northern Australia will lose native mammal species. This problem needs to be solved. The fi rst step towards a solution is to recognise the problem, and this publication seeks to alert the Australian community and decision makers to this urgent issue. -

Fowlers Gap Biodiversity Checklist Reptiles

Fowlers Gap Biodiversity Checklist ow if there are so many lizards then they should make tasty N meals for someone. Many of the lizard-eaters come from their Reptiles own kind, especially the snake-like legless lizards and the snakes themselves. The former are completely harmless to people but the latter should be left alone and assumed to be venomous. Even so it odern reptiles are at the most diverse in the tropics and the is quite safe to watch a snake from a distance but some like the Md rylands of the world. The Australian arid zone has some of the Mulga Snake can be curious and this could get a little most diverse reptile communities found anywhere. In and around a disconcerting! single tussock of spinifex in the western deserts you could find 18 species of lizards. Fowlers Gap does not have any spinifex but even he most common lizards that you will encounter are the large so you do not have to go far to see reptiles in the warmer weather. Tand ubiquitous Shingleback and Central Bearded Dragon. The diversity here is as astonishing as anywhere. Imagine finding six They both have a tendency to use roads for passage, warming up or species of geckos ranging from 50-85 mm long, all within the same for display. So please slow your vehicle down and then take evasive genus. Or think about a similar diversity of striped skinks from 45-75 action to spare them from becoming a road casualty. The mm long! How do all these lizards make a living in such a dry and Shingleback is often seen alone but actually is monogamous and seemingly unproductive landscape? pairs for life. -

Expert Report of Professor Woinarski

NOTICE OF FILING This document was lodged electronically in the FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA (FCA) on 18/01/2019 3:23:32 PM AEDT and has been accepted for filing under the Court’s Rules. Details of filing follow and important additional information about these are set out below. Details of Filing Document Lodged: Expert Report File Number: VID1228/2017 File Title: FRIENDS OF LEADBEATER'S POSSUM INC v VICFORESTS Registry: VICTORIA REGISTRY - FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA Dated: 18/01/2019 3:23:39 PM AEDT Registrar Important Information As required by the Court’s Rules, this Notice has been inserted as the first page of the document which has been accepted for electronic filing. It is now taken to be part of that document for the purposes of the proceeding in the Court and contains important information for all parties to that proceeding. It must be included in the document served on each of those parties. The date and time of lodgment also shown above are the date and time that the document was received by the Court. Under the Court’s Rules the date of filing of the document is the day it was lodged (if that is a business day for the Registry which accepts it and the document was received by 4.30 pm local time at that Registry) or otherwise the next working day for that Registry. No. VID 1228 of 2017 Federal Court of Australia District Registry: Victoria Division: ACLHR FRIENDS OF LEADBEATER’S POSSUM INC Applicant VICFORESTS Respondent EXPERT REPORT OF PROFESSOR JOHN CASIMIR ZICHY WOINARSKI Contents: 1. -

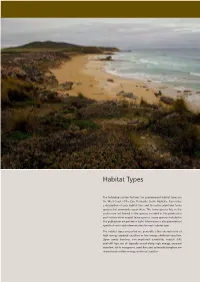

Habitat Types

Habitat Types The following section features ten predominant habitat types on the West Coast of the Eyre Peninsula, South Australia. It provides a description of each habitat type and the native plant and fauna species that commonly occur there. The fauna species lists in this section are not limited to the species included in this publication and include other coastal fauna species. Fauna species included in this publication are printed in bold. Information is also provided on specific threats and reference sites for each habitat type. The habitat types presented are generally either characteristic of high-energy exposed coastline or low-energy sheltered coastline. Open sandy beaches, non-vegetated dunefields, coastal cliffs and cliff tops are all typically found along high energy, exposed coastline, while mangroves, sand flats and saltmarsh/samphire are characteristic of low energy, sheltered coastline. Habitat Types Coastal Dune Shrublands NATURAL DISTRIBUTION shrublands of larger vegetation occur on more stable dunes and Found throughout the coastal environment, from low beachfront cliff-top dunes with deep stable sand. Most large dune shrublands locations to elevated clifftops, wherever sand can accumulate. will be composed of a mosaic of transitional vegetation patches ranging from bare sand to dense shrub cover. DESCRIPTION This habitat type is associated with sandy coastal dunes occurring The understory generally consists of moderate to high diversity of along exposed and sometimes more sheltered coastline. Dunes are low shrubs, sedges and groundcovers. Understory diversity is often created by the deposition of dry sand particles from the beach by driven by the position and aspect of the dune slope.