Natural History of the Eutheria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monitoring Program – Fauna

Procedure Document No. 2663 Document Title Monitoring Program – Fauna Area HSE Issue Date Major Process Environment Sub Process Authoriser Jacqui McGill – Asset President Version Number 19 Olympic Dam 1 SCOPE..................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Responsible ODC personnel ........................................................................................... 2 1.2 Review and modification ................................................................................................. 2 2 DETAILED PROCEDURE ........................................................................................................ 3 2.1 Feral and abundant species ............................................................................................ 3 2.2 ‘At-risk’ fauna – Category 1a ........................................................................................... 3 2.3 ‘At-risk’ fauna – Categories 1b and 2 ............................................................................... 4 2.4 Fauna losses .................................................................................................................. 5 3 COMMITMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 7 3.1 Reporting ........................................................................................................................ 7 3.2 Summary of commitments.............................................................................................. -

Checklist of the Mammals of Indonesia

CHECKLIST OF THE MAMMALS OF INDONESIA Scientific, English, Indonesia Name and Distribution Area Table in Indonesia Including CITES, IUCN and Indonesian Category for Conservation i ii CHECKLIST OF THE MAMMALS OF INDONESIA Scientific, English, Indonesia Name and Distribution Area Table in Indonesia Including CITES, IUCN and Indonesian Category for Conservation By Ibnu Maryanto Maharadatunkamsi Anang Setiawan Achmadi Sigit Wiantoro Eko Sulistyadi Masaaki Yoneda Agustinus Suyanto Jito Sugardjito RESEARCH CENTER FOR BIOLOGY INDONESIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCES (LIPI) iii © 2019 RESEARCH CENTER FOR BIOLOGY, INDONESIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCES (LIPI) Cataloging in Publication Data. CHECKLIST OF THE MAMMALS OF INDONESIA: Scientific, English, Indonesia Name and Distribution Area Table in Indonesia Including CITES, IUCN and Indonesian Category for Conservation/ Ibnu Maryanto, Maharadatunkamsi, Anang Setiawan Achmadi, Sigit Wiantoro, Eko Sulistyadi, Masaaki Yoneda, Agustinus Suyanto, & Jito Sugardjito. ix+ 66 pp; 21 x 29,7 cm ISBN: 978-979-579-108-9 1. Checklist of mammals 2. Indonesia Cover Desain : Eko Harsono Photo : I. Maryanto Third Edition : December 2019 Published by: RESEARCH CENTER FOR BIOLOGY, INDONESIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCES (LIPI). Jl Raya Jakarta-Bogor, Km 46, Cibinong, Bogor, Jawa Barat 16911 Telp: 021-87907604/87907636; Fax: 021-87907612 Email: [email protected] . iv PREFACE TO THIRD EDITION This book is a third edition of checklist of the Mammals of Indonesia. The new edition provides remarkable information in several ways compare to the first and second editions, the remarks column contain the abbreviation of the specific island distributions, synonym and specific location. Thus, in this edition we are also corrected the distribution of some species including some new additional species in accordance with the discovery of new species in Indonesia. -

Platypus Collins, L.R

AUSTRALIAN MAMMALS BIOLOGY AND CAPTIVE MANAGEMENT Stephen Jackson © CSIRO 2003 All rights reserved. Except under the conditions described in the Australian Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, duplicating or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Contact CSIRO PUBLISHING for all permission requests. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Jackson, Stephen M. Australian mammals: Biology and captive management Bibliography. ISBN 0 643 06635 7. 1. Mammals – Australia. 2. Captive mammals. I. Title. 599.0994 Available from CSIRO PUBLISHING 150 Oxford Street (PO Box 1139) Collingwood VIC 3066 Australia Telephone: +61 3 9662 7666 Local call: 1300 788 000 (Australia only) Fax: +61 3 9662 7555 Email: [email protected] Web site: www.publish.csiro.au Cover photos courtesy Stephen Jackson, Esther Beaton and Nick Alexander Set in Minion and Optima Cover and text design by James Kelly Typeset by Desktop Concepts Pty Ltd Printed in Australia by Ligare REFERENCES reserved. Chapter 1 – Platypus Collins, L.R. (1973) Monotremes and Marsupials: A Reference for Zoological Institutions. Smithsonian Institution Press, rights Austin, M.A. (1997) A Practical Guide to the Successful Washington. All Handrearing of Tasmanian Marsupials. Regal Publications, Collins, G.H., Whittington, R.J. & Canfield, P.J. (1986) Melbourne. Theileria ornithorhynchi Mackerras, 1959 in the platypus, 2003. Beaven, M. (1997) Hand rearing of a juvenile platypus. Ornithorhynchus anatinus (Shaw). Journal of Wildlife Proceedings of the ASZK/ARAZPA Conference. 16–20 March. -

Calaby References

Abbott, I.J. (1974). Natural history of Curtis Island, Bass Strait. 5. Birds, with some notes on mammal trapping. Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 107: 171–74. General; Rodents; Abbott, I. (1978). Seabird islands No. 56 Michaelmas Island, King George Sound, Western Australia. Corella 2: 26–27. (Records rabbit and Rattus fuscipes). General; Rodents; Lagomorphs; Abbott, I. (1981). Seabird Islands No. 106 Mondrain Island, Archipelago of the Recherche, Western Australia. Corella 5: 60–61. (Records bush-rat and rock-wallaby). General; Rodents; Abbott, I. and Watson, J.R. (1978). The soils, flora, vegetation and vertebrate fauna of Chatham Island, Western Australia. Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia 60: 65–70. (Only mammal is Rattus fuscipes). General; Rodents; Adams, D.B. (1980). Motivational systems of agonistic behaviour in muroid rodents: a comparative review and neural model. Aggressive Behavior 6: 295–346. Rodents; Ahern, L.D., Brown, P.R., Robertson, P. and Seebeck, J.H. (1985). Application of a taxon priority system to some Victorian vertebrate fauna. Fisheries and Wildlife Service, Victoria, Arthur Rylah Institute of Environmental Research Technical Report No. 32: 1–48. General; Marsupials; Bats; Rodents; Whales; Land Carnivores; Aitken, P. (1968). Observations on Notomys fuscus (Wood Jones) (Muridae-Pseudomyinae) with notes on a new synonym. South Australian Naturalist 43: 37–45. Rodents; Aitken, P.F. (1969). The mammals of the Flinders Ranges. Pp. 255–356 in Corbett, D.W.P. (ed.) The natural history of the Flinders Ranges. Libraries Board of South Australia : Adelaide. (Gives descriptions and notes on the echidna, marsupials, murids, and bats recorded for the Flinders Ranges; also deals with the introduced mammals, including the dingo). -

Thylacinidae

FAUNA of AUSTRALIA 20. THYLACINIDAE JOAN M. DIXON 1 Thylacine–Thylacinus cynocephalus [F. Knight/ANPWS] 20. THYLACINIDAE DEFINITION AND GENERAL DESCRIPTION The single member of the family Thylacinidae, Thylacinus cynocephalus, known as the Thylacine, Tasmanian Tiger or Wolf, is a large carnivorous marsupial (Fig. 20.1). Generally sandy yellow in colour, it has 15 to 20 distinct transverse dark stripes across the back from shoulders to tail. While the large head is reminiscent of the dog and wolf, the tail is long and characteristically stiff and the legs are relatively short. Body hair is dense, short and soft, up to 15 mm in length. Body proportions are similar to those of the Tasmanian Devil, Sarcophilus harrisii, the Eastern Quoll, Dasyurus viverrinus and the Tiger Quoll, Dasyurus maculatus. The Thylacine is digitigrade. There are five digital pads on the forefoot and four on the hind foot. Figure 20.1 Thylacine, side view of the whole animal. (© ABRS)[D. Kirshner] The face is fox-like in young animals, wolf- or dog-like in adults. Hairs on the cheeks, above the eyes and base of the ears are whitish-brown. Facial vibrissae are relatively shorter, finer and fewer than in Tasmanian Devils and Quolls. The short ears are about 80 mm long, erect, rounded and covered with short fur. Sexual dimorphism occurs, adult males being larger on average. Jaws are long and powerful and the teeth number 46. In the vertebral column there are only two sacrals instead of the usual three and from 23 to 25 caudal vertebrae rather than 20 to 21. -

Mammals of Fleurieu Peninsula This List of Mammals of Fleurieu Peninsula Was Applied by the Late P.F

Mammals of Fleurieu Peninsula This list of mammals of Fleurieu Peninsula was applied by the late P.F. Aitken, onetime Curator of Mammals at the South Australian Museum. Additional information was obtained from surveys of Deep Creek Conservation Park in December 1971, January 1972, January 1980 and January 1984 by the Mammal Club, Field Naturalists Society of South Australia (R. Thomas, personal communication). Introduced species are indicated by an asterisk. RECORDED IN SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME HABITAT DEEP CREEK CONS. PARK Antechinus Flavipes Yellow-footed Antechinus Woodland, eucalypt forest Yes Cercartetus concinnus South western Pigmy Possum Scrub to eucalypt forest No Chalinolobus gouldii Gould's wattled Bat Scrub to open-forest (mainly tree spouts) Yes Chalinolobus moria Chocolate Wattled Bat Scrub to open-forest (tree spouts) No Eptesicus sp. Eptesicus Scrub to open-forest (tree spouts) Yes *Felis calus Cat (feral) Cosmopolitan Yes Hydromys chrysogaster Water Rat Creeks No Isoodon obesulus Southern Brown Bandicoot Dense understorey Yes *Lepus capensis Brown Hare Grasslands Yes Macropus fuliginosus Western Grey Kangaroo Heath to eucalypt forest Yes Miniopterus schreibersii Common Bent-wing Ba Eucalypt forest (caves) No *Mus musculus House Mouse Disturbed areas and early fire succession Yes Nyctophilus geoffroy Lesser Long-eared Bat Scrub to forest, semi cleared pasture (tree spouts, buildings) Yes *Oryctolagus cuniculus Rabbit Grasslands and disturbed areas Yes Pseudocheirus peregrinus Common Ringtail Coastal scrub to eucalypt -

Quaternary Murid Rodents of Timor Part I: New Material of Coryphomys Buehleri Schaub, 1937, and Description of a Second Species of the Genus

QUATERNARY MURID RODENTS OF TIMOR PART I: NEW MATERIAL OF CORYPHOMYS BUEHLERI SCHAUB, 1937, AND DESCRIPTION OF A SECOND SPECIES OF THE GENUS K. P. APLIN Australian National Wildlife Collection, CSIRO Division of Sustainable Ecosystems, Canberra and Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Mammalogy) American Museum of Natural History ([email protected]) K. M. HELGEN Department of Vertebrate Zoology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution, Washington and Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Mammalogy) American Museum of Natural History ([email protected]) BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY Number 341, 80 pp., 21 figures, 4 tables Issued July 21, 2010 Copyright E American Museum of Natural History 2010 ISSN 0003-0090 CONTENTS Abstract.......................................................... 3 Introduction . ...................................................... 3 The environmental context ........................................... 5 Materialsandmethods.............................................. 7 Systematics....................................................... 11 Coryphomys Schaub, 1937 ........................................... 11 Coryphomys buehleri Schaub, 1937 . ................................... 12 Extended description of Coryphomys buehleri............................ 12 Coryphomys musseri, sp.nov.......................................... 25 Description.................................................... 26 Coryphomys, sp.indet.............................................. 34 Discussion . .................................................... -

Management of the Terrestrial Small Mammal and Lizard Communities in the Dune System Of

Management of the terrestrial small mammal and lizard communities in the dune system of Sturt National Park, Australia: Historic and contemporary effects of pastoralism and fox predation Ulrike Sabine Klöcker (Dipl. – Biol., Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms Universität Bonn, Germany) Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences The University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia 2009 Abstract This thesis addressed three issues related to the management and conservation of small terrestrial vertebrates in the arid zone. The study site was an amalgamation of pastoral properties forming the now protected area of Sturt National Park in far-western New South Wales, Australia. Thus firstly, it assessed recovery from disturbance accrued through more than a century of Sheep grazing. Vegetation parameters, Fox, Cat and Rabbit abundance, and the small vertebrate communities were compared, with distance to watering points used as a surrogate for grazing intensity. Secondly, the impacts of small-scale but intensive combined Fox and Rabbit control on small vertebrates were investigated. Thirdly, the ecology of the rare Dusky Hopping Mouse (Notomys fuscus) was used as an exemplar to illustrate and discuss some of the complexities related to the conservation of small terrestrial vertebrates, with a particular focus on desert rodents. Thirty-five years after the removal of livestock and the closure of watering points, areas that were historically heavily disturbed are now nearly indistinguishable from nearby relatively undisturbed areas, despite uncontrolled native herbivore (kangaroo) abundance. Rainfall patterns, rather than grazing history, were responsible for the observed variation between individual sites and may overlay potential residual grazing effects. -

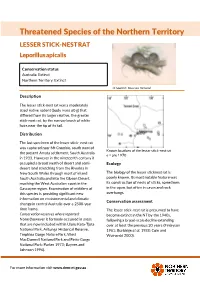

LESSER STICK-NEST RAT Leporillus Apicalis

Threatened Species of the Northern Territory LESSER STICK-NEST RAT Leporillus apicalis Conservation status Australia: Extinct Northern Territory: Extinct (J Gould © Museum Victoria) Description The lesser stick-nest rat was a moderately sized native rodent (body mass 60 g) that differed from its larger relative, the greater stick-nest rat, by the narrow brush of white hairs near the tip of its tail. Distribution The last specimen of the lesser stick- nest rat was captured near Mt Crombie, south west of Known locations of the lesser stick-nest rat the present Amata settlement, South Australia ο = pre 1970 in 1933. However in the nineteenth century it occupied a broad swath of desert and semi- Ecology desert land stretching from the Riverina in New South Wales through most of inland The biology of the lesser sticknest rat is South Australia and into the Gibson Desert, poorly known. Its most notable feature was reaching the West Australian coast in the its construction of nests of sticks, sometimes Gascoyne region. Examination of middens of in the open, but often in caves and rock this species is providing significant new overhangs. information on environmental and climatic Conservation assessment change in central Australia over a 2500-year time frame. The lesser stick-nest rat is presumed to have Conservation reserves where reported: become extinct in the NT by the 1940s, None (however it formerly occurred in areas following a broad-scale decline extending that are now included within Uluru Kata-Tjuta over at least the previous 30 years (Finlayson National Park, Arltunga Historical Reserve, 1961; Burbidge et al. -

Factsheet: a Threatened Mammal Index for Australia

Science for Saving Species Research findings factsheet Project 3.1 Factsheet: A Threatened Mammal Index for Australia Research in brief How can the index be used? This project is developing a For the first time in Australia, an for threatened plants are currently Threatened Species Index (TSX) for index has been developed that being assembled. Australia which can assist policy- can provide reliable and rigorous These indices will allow Australian makers, conservation managers measures of trends across Australia’s governments, non-government and the public to understand how threatened species, or at least organisations, stakeholders and the some of the population trends a subset of them. In addition to community to better understand across Australia’s threatened communicating overall trends, the and report on which groups of species are changing over time. It indices can be interrogated and the threatened species are in decline by will inform policy and investment data downloaded via a web-app to bringing together monitoring data. decisions, and enable coherent allow trends for different taxonomic It will potentially enable us to better and transparent reporting on groups or regions to be explored relative changes in threatened understand the performance of and compared. So far, the index has species numbers at national, state high-level strategies and the return been populated with data for some and regional levels. Australia’s on investment in threatened species TSX is based on the Living Planet threatened and near-threatened birds recovery, and inform our priorities Index (www.livingplanetindex.org), and mammals, and monitoring data for investment. a method developed by World Wildlife Fund and the Zoological A Threatened Species Index for mammals in Australia Society of London. -

Ba3444 MAMMAL BOOKLET FINAL.Indd

Intot Obliv i The disappearing native mammals of northern Australia Compiled by James Fitzsimons Sarah Legge Barry Traill John Woinarski Into Oblivion? The disappearing native mammals of northern Australia 1 SUMMARY Since European settlement, the deepest loss of Australian biodiversity has been the spate of extinctions of endemic mammals. Historically, these losses occurred mostly in inland and in temperate parts of the country, and largely between 1890 and 1950. A new wave of extinctions is now threatening Australian mammals, this time in northern Australia. Many mammal species are in sharp decline across the north, even in extensive natural areas managed primarily for conservation. The main evidence of this decline comes consistently from two contrasting sources: robust scientifi c monitoring programs and more broad-scale Indigenous knowledge. The main drivers of the mammal decline in northern Australia include inappropriate fi re regimes (too much fi re) and predation by feral cats. Cane Toads are also implicated, particularly to the recent catastrophic decline of the Northern Quoll. Furthermore, some impacts are due to vegetation changes associated with the pastoral industry. Disease could also be a factor, but to date there is little evidence for or against it. Based on current trends, many native mammals will become extinct in northern Australia in the next 10-20 years, and even the largest and most iconic national parks in northern Australia will lose native mammal species. This problem needs to be solved. The fi rst step towards a solution is to recognise the problem, and this publication seeks to alert the Australian community and decision makers to this urgent issue. -

Australian Archaeology

Australian Archaeology Archived at Flinders University: dspace.flinders.edu.au Full Citation Details: White, J.P, 1974. Man in Australia: Present and Past. 'Australian Archaeology', no.1, 28-43. MAN IN AUSTRALIA : PRESENT AND PAST Human history is first of all the history of hunting and gathering communities. More than 99% of tool-making man's time on earth has been occupied by this way of life. Agriculture, cities and atomic weapons are, by comparison, an almost instant- aneous and probably unstable development out of a long and highly successful adaptation. Today, almost all hunting and gathering societies are extinct, crushed out of existence by the population densities and cultural intolerances of agricultural man. There are now no communities which remain unaffected by the modern industrial world, which is unable to tolerate any exclusions from its hegemony. Australia is the continent most recently intruded on by machine-age man. Consequently its hunters and gatherers, the Aborigines, represent the longest-lived and least externally- affected of all societies practising this economy. They can demonstrate, more clearly than any other communities, the potentials and handicaps of that way of life. This is not to imply that Australian Aborigines are representatives of Palaeolithic man, except insofar as any sample group, when studied from a particular viewpoint, may be said to embody some of the characteristics of the whole groupasdefined by that viewpoint. What the Australian Aborigines can teach us is how men and women have lived, adapted, created and innovated without so many of those mechanical aids which today we regard as essential.