Advisory Comnittee on Evidence Rules Washington, D.C. April 22-23, 1996

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

206 Kappa Phi 1.Pdf

A PETITION TO THE INTERNATIONAL FRATERNITY OF DELTA SIGMA PI BY KAPPA BETA ALPHA PROFESSIONAL BUSINESS FRATERNITY VALPARAISO UNIVERSITY VALPARAISO,, INDIANA 'Valparaiso University ^ ^ College of Business Administration Office of the Dean Valparaiso, Indiana 46383 February 22,1983 International Fraternity of Delta Sigma Pi c/o Mark Roberts 330 South Campus Avenue Oxford, OH 1^5056 Gentlemens We, the brothers of Kappa Beta Alpha, a Professional Business Fraternity at Valparaiso University, submit for your consideration this petition for acceptance. Our group was formed by students in the College of Business Administration who hoped to broaden their scope through professional programs. With this idea we hope to better our campus and the community of Valparaiso Surrounding it. We set our standards high, as does Delta Sigma Pi, and are constantly working to meet them. The honor of being accepted as a charter of Delta Sigma Pi woui^l be of mutual benefit to all concerned. We would promote the values and high standards of Delta Sigma Pi, and in turn Delta Sigma Pi could enable us to reach more people inside and outside our coramiinity. Therefore, we ask that you grant Kappa Beta Alpha a charter so that we may establish a chapter of the International Fratemity of Delta Sigma Pi on the Valparaiso University campus. Respectfully, The Brothers of Kappa BetaAlpha dAyujJd ^naicMuiu'^ /Ul^f-'O-^-r^ (^ta. Jk<^AA:6U LETTERS OF RECOMMENDATION Valparaiso University 5? College of Business Administration Valparaiso, Indiana Office of tfie Dean 46383 December 28, 1982 Mr. Mark Roberts Director of Chapter Operations Delta Sigma Pi 330 South Campus Avenue P.O. -

Advisory Committee Civil Rules

ADVISORY COMMITTEE 7K ON CIVIL RULES WASHINGTON, D.C. MAY 3-5, 1993 L L I17 l lV H H H H I X K I ~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ | F, LI I7 I~~~~~~ H H El, Li 7 S-- LE Tentative Agenda Meeting of Advisory Committee on Civil Rules Federal Judiciary Building Washington, DC May 3-5, 1993 I. Welcome of new members; Orientation. II. Report on status of pending amendments. If Supreme Court returns any amendments for further consideration, we'll 7 probably take these up at this point.) III. Revisiting proposals previously considered. Ed Cooper will be sending out separately to each member his latest work on these. He has received various comments and suggestions from the groups and individuals to whom he sent drafts on an informal basis. Rule 23 tF. Rule 26(c) (sunshine/confidentiality) Rule 43 7 Rule 68 (also possible FJC study) L Rule 83 Rule 84 t IV. Style Revision. Enjoy yourself. V. New Matters. We have received a variety of suggestions for changes. We'll need to discuss them briefly to decide which we might want to go forward with. I'm asking Ed and John Rabiej to go through their correspondence to make a list. Among the items I'm aware of: Rules 7 and 11 (signature requirement for electronic filing); Rule 45 (expansion of trial subpoena jurisdiction); Rules 52 and 59 (requirement for 10- day filing--not merely serving); Rule 53 (expansion of role of Master to discovery/pretrial areas); Rule 64 (ABA proposal--legislative action). VI. Plans for future meetings, submissions to Standing Committee, etc. -

Of 65 NIRPC ADA PUBLIC HEARING 6/11/13 CART & Transcription

Page 1 of 65 1 NIRPC ADA PUBLIC HEARING 2 PURDUE CALUMET LIBRARY 3 HAMMOND, IN 4 JUNE 11, 2013 5 1-4 p.m. 6 7 8 CART SERVICES AND VERBATIM TRANSCRIPTION SERVICES 9 PROVIDED BY: 10 VOICE TO PRINT CAPTIONING, LLC 11 9800 Connecticut Drive 12 Crown Point, IN 46307 13 219-644-3220 14 www.voicetoprint.com 15 [email protected] 16 NIRPC ADA PUBLIC HEARING 6/11/13 CART & Transcription by Voice to Print Captioning Page 2 of 65 17 >> GAIL BARKER: Hello. My name is Gail Barker, the 18 Disability Coordinator at Purdue North Central. I will be 19 serving as the facilitator of this year's public hearing for the 20 Northwestern Indiana Regional Planning Commission. I would like 21 to welcome those who are here at Purdue University Calumet for 22 our 2013 public hearing. I would also like to welcome those 23 that are watching on the Internet and those that are watching 24 from the site at LaPorte, Indiana also on the Internet. 25 NIRPC, as the agency is called, is a Metropolitan Planning 26 Organization that is responsible for regional transportation 27 planning in Lake, Porter and LaPorte Counties. 28 This hearing is being held as a result of a Class Action 29 ADA transportation lawsuit which was filed in 1997. ADA stands 30 for the Americans with Disabilities Act, which was enacted into 31 law in 1990. The lawsuit settlement, which was reached in 2006, 32 requires NIRPC to have an independent ADA review each year of 33 all its subgrantees; that is, all the public transit providers 34 for whom NIRPC provides monitoring and oversight. -

East Chicago Junior Police: an Effective Project in the Non-Academic Area of the School's Total Educational Attack on the Disadvantagement of Youth

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 053 241 UD 011 713 TITLE East Chicago Junior Police: An Effective Project in the Non-Academic Area of the School's Total Educational Attack on the Disadvantagement of Youth. INSTITUTION East Chicago City School District, Ind: PUB DATE Dec 70 NOTE 65p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS After School Programs, Behavior Problems, Child Development, *Delinquency Prevention, *Disadvantaged Youth, Health Activities, Music Activities, *Police School Relationship, Program Descriptions, Program Design, Program Effectiveness, Program Evaluation, School Community Programs, Volunteers, Youth Clubs, Youth Problems, *Youth Programs IDENTIFIERS *East Chicago Junior Police, Elementary Secondary Education Title I, Indiana ABSTRACT The Junior Police program utilized non-academic youth interests as its foundation. The project filled the need for a youth organization, a youth clearinghouse, and more aid to delinquent and predelinquent youth to redirect them into ways of thinking and acting beneficial both to themselves and to the community. The objectives of the program were to provide supplemental effort in attacking conditions which interfere with a child's educational growth--those conditions, being underachievement, social, cultural, and nutritional disadvantagement, and health deficiencies. Program areas included were music, arts and crafts, sports, health, cosmetology, business, hobbies, field trips, and parties. Both professionals and volunteers comprised the staff including members of the East Chicago police and fire departments. Those working with the program submit that the Junior Police members have been involved in fewer incidents of delinquency than non-members. (Author/CB) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT fiAS BEEN REPRO- OUCED EXACTLY /.S RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG- INATING IT. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 112 164 CE 004 982 TITLE Indiana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 112 164 CE 004 982 TITLE Indiana Career Resource Center: Annual Report: 1974-75. INSTITUTION Indiana Univ., South Bend. Indiana Career Resource Center. PUB DATE [75] NOTE 207p.; Portions of Appendix N may not be completely legible in microfiche; Not available in hard copy due to paper color of original document EDRS PRICE LIF-$0.76 Plus Postage. HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Annual Reports; *Career Education; Educational Development; *Educational Programs; Educational Resources; Letters (Correspondence); Questionnaires; *Resource Centers; Resource Materials; Teaching Techniques IDENTIFIERS Career Information Centers; *Indiana ABSTRACT The report presents an account of the activities and progress of the Indiana Career Resource Center in its sixth year as a source of ideas and programs for educators developing their own career education programs. It documents the services offered: (1) inservice and preservice training of classroom teachers, student teachers, counselors, administrators, and school board and community members in the concepts and involvement of a career education program;(2) editing and producing media to assist educators, including a career education specialty training directory; (3) developing contacts in the local community and becoming involved with local projects as a means of piloting ideas that could be duplicated in other settings (women's career center, career guidance institute, life planning, conference telephone use in career education) and career development workshops for the Comprehensive -

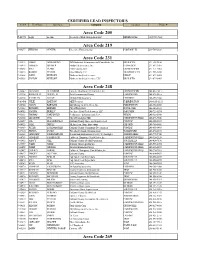

Area Code 205 Area Code 219 Area Code 231 Area

CERTIFIED LEAD INSPECTOR'S Cert # First Name Last Name Company Location Phone # Area Code 205 P-01571 Leigh Lachine Accelerated Risk Management LLC BIRMINGHAM (205)533-7662 Area Code 219 P-04277 WILLIAM CENTER Greentree Environmental PORTAGE, IN 219-764-2828 Area Code 231 P-01412 JAMES ARMSTRONG ARM Industrial & Environmental Consultants, Inc. BIG RAPIDS 231-592-9858 P-06974 HAROLD BROWER Norlund & Associates, Inc. LUDINGTON 231-843-3485 P-06268 KYLE CLARK PM Environmental GRAND RAPIDS 231-571-3082 P-00013 ROBERT PETERS Otwell Mawby P.C. TRAVERSE CITY 231-946-5200 P-01268 JOHN REHKOPF Northern Analytical Services LEROY 231-679-0005 P-05558 JUSTON REHKOPF Northern Analytical Services, LLC BIG RAPIDS 231-679-0005 Area Code 248 P-06647 ALI SALIH AL-HADDAD Fisbeck, Thompson, Carr & Huber, Inc. GRAND RAPIDS 248-410-7411 P-02334 ROOSEVELT AUSTIN, III Arch Environmental Group FARMINGTON 248-426-0165 P-06124 KATHLEEN BALAZE McDowell & Associates FERNDALE 248-399-2066 P-03480 JULIE BARTON AKT Peerless FARMINGTON 248-615-1333 P-04724 JASON BARYLSKI IAQ Management Services, Inc. FARMINGTON 248-932-8800 P-01082 RICHARD BREMER City of Royal Oak ROYAL OAK 248-246-3133 P-04983 JOSEPH BURLEY Freelance Envir-Tech Services, LLC OAK PARK 248-721-8574 P-05333 THOMAS CARPENTER Performance Environmental Serv. WIXOM 248-926-3800 P-06860 LEE EDWIN COX City of Farmington Hills FARMINGTON HILLS 248-473-9546 P-00657 JOE DEL MORONE II Oakland County Home and Improvement PONTIAC 248-858-5307 P-04823 JANE DIPPLE All American Home Inspections OXFORD 248-760-5441 P-00869 PETER ESSENMACHER Oakland County Community Development PONTIAC 248-858-0493 P-07010 DONNA EVANS Waterford Schools Transportation WATERFORD 248-674-2692 P-06262 GREGORY FAHRENBRUCH Restoration Environmental Safety Technologies AUBURN HILLS 248-778-5940 P-04763 JENNIFER FASHBAUGH Fishbeck, Thmpson, Carr & Huber, Inc. -

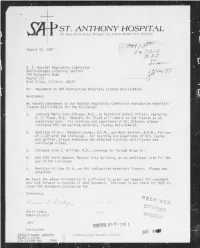

Application for Amend to License 13-13144-012,Authorizing MJ

__-_ _ '' -' 's . - ' . h - ST. ANTHONY HOSPITAL , 301 West Horner Street. Michigan City, Indiana 46360 (219) 879 8511 .A August 12, 1987 |r- c-&| g,, p . i [/ 48 #W- U. S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission | Radioisotopes Licensing Section /d M[[[ | 799 Roosevelt Road Region Ill ------ v -- Glen Ellyn, Illinois 60137 Re: Amendment to NRC Radioactive Materials License #13-13144-02 Gentlemen: We request amendment to our Nuclear Regulatory Commission radioactive materials license #13-13144-02 for the following: 1. Indicate Marco John DiBiase, M.D., as Radiation Safety Officer, replacing R. S. Plank, M.D. However, Dr. Plank will remain on the license as an authorized user. For training and experience of Dr. DiBiase, please reference NRC radioactive materials license #13-13144-02. 2. Addition of Drs. Theodore Leonas, D.F.M., and Mann Spitler, D.P.M., for use of I-125 with the Lixiscope. For training and experience of Drs. Leonas and Spitler, please reference the attached training certificates and curriculum vitaes. 3. Increase Alan C. William, M.D., coverage to include Group VI. 4. Add 1501 North Wabash, Medical Arts Building, as an additional site fcr the use of the Lixiscope- 5. Revision of Item 10 to our NRC radioactive materials license. Please see attached. We trust the above information is sufficient to grant our request for amendment and look forward to receipt of that document. Enclosed is our check for $120 to cover the amendment processing fee. Sincerely, ? /{IA AhbA , I l G E B- 'YED 919r/- ! Kevin Leahy 1 inn Administrator UCIOllyg7 *d** CONTR0l. N0 84281 Enclosures gg7 gg B9022704B9 BB0301 " Celebrating Eight Decades of Service" REG 3 LIC30 13-13144-02 PNV _ _ _ _ _ _ _ - _ _ _ _ _ - ' ~* , . -

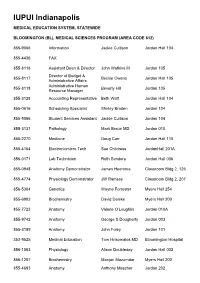

Department PDF: IU Directory

IUPUI Indianapolis MEDICAL EDUCATION SYSTEM, STATEWIDE BLOOMINGTON (BL), MEDICAL SCIENCES PROGRAM (AREA CODE 812) 855-9066 Information Jackie Cullison Jordan Hall 104 855-4436 FAX 855-8118 Assistant Dean & Director John Watkins III Jordan 105 Director of Budget & 855-8117 Beckie Owens Jordan Hall 105 Administrative Affairs Administrative Human 855-8118 Beverly Hill Jordan 105 Resource Manager 855-3128 Accounting Representative Beth Watt Jordan Hall 104 855-0616 Scheduling Specialist Shirley Braden Jordan 104 855-9066 Student Services Assistant Jackie Cullison Jordan 104 855-3131 Pathology Mark Braun MD Jordan 010 855-2270 Medicine Doug Carr Jordan Hall 110 855-4164 Electronicmicro Tech Sue Childress JordanHall 201A 856-0171 Lab Technician Ruth Sanders Jordan Hall 006 855-0948 Anatomy Demonstrator James Heersma Classroom Bldg 2, 126 855-4774 Physiology Demonstrator JW Ramsey Classroom Bldg 2, 207 856-5304 Genetics Wayne Forrester Myers Hall 254 855-6902 Biochemistry David Daleke Myers Hall 200 855-7723 Anatomy Valerie O’Loughlin Jordan 010A 855-9742 Anatomy George S Dougherty Jordan 003 855-3189 Anatomy John Foley Jordan 101 353-9525 Medical Education Tom Hrisomalos MD Bloomington Hospital 856-1063 Physiology Alison Doubleday Jordan Hall 002 856-1207 Biochemistry Manjari Mazumdar Myers Hall 200 855-4693 Anatomy Anthony Mescher Jordan 202 855-9067 Physiology Richard Mynark Jordan 004 855-0982 Physiology Bruce Martin Jordan Hall 200 855-9445 Physiology Kenneth Nephew Jordan 302 855-3788 Physiology Andrew Notebaert Jordan 010 855-8411 Physiology -

Indiana Architect Une 1964 Sculptured

INDIANA ARCHITECT UNE 1964 SCULPTURED GALAXY PAT. NO. 193 002 STRUCTURAL GLAZED FACING TILE . DESIGN VERSATILITY Starks' exclusive deep-sculptured patterns provide a new dimension to structural tile walls. These 5 contemporary designs offer design flexibility, permanent glazed finish, initial economy and the lowest possible maintenance. Stark Sculptured Glazed Tile is available in 8W series with face dimensions of 8" x 16" and in all of Stark's engineered colors. Galaxy pattern is also available with 2-color glazing . indented stars may be accented with harmonizing or contrasting glaze. FREE FORM HERRINGBONE . Indented free-form line May be installed running or makes continuous pattern stack bond. Forms attrac• when installed running tive overall pattern. bond. r I LOUVER CLASSIC Pat. No. 195-334 Ideal pattern for stack Strong vertical form may bond. Particularly suited be installed running or for decorative inserts and slack bond. Ideal to create panels. feature strips. FULL SERVICE We will be most happy to be of service at any time during your planning, specifying, bidding or build• ing. Full information including sizes, colors, sam• ples and prices are available , . You'll find us convenient to write or call. LUTHER LEE ODA—Indiana representative p. 0. Box 17 BLUFFTON, INDIANA (Indianapolis ME 4-1361) 3§r» Architect: .for interiors that are compatible with your original concept of the building... ARCMrrerTs JUN 3 0 1964 LIBRARY Business Furniture Corporation Business Furniture Corporation • A well staffed delivery and service wishes -

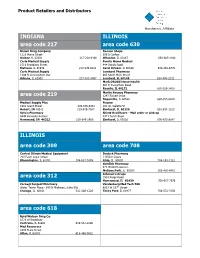

INDIANA ILLINOIS Area Code 217 Area Code 630 Area Code 219

Product Retailers and Distributors Northern IL Affiliate INDIANA ILLINOIS area code 217 area code 630 Brown Drug Company Denson Shops 1121 Maine Street 509 S Carlton Quincy, IL 62301 217-228-6400 Wheaton, IL 60187 630-665-1488 Carle Medical Supply Family Home Medical 1016 Broadway Street 444 Randy Road Mattoon, IL 61938 217-235-6421 Carol Stream, IL 60188 630-462-6770 Carle Medical Supply Lombard Pharmacy 1208 N Cunningham Ave 805 South Main Street Urbana, IL 61802 217-383-3487 Lombard, IL 60148 630-495-2333 Mark DRUGS Home Health 384 E Irving Park Road Roselle, IL 60172 630-529-3400 Martin Avenue Pharmacy area code 219 1247 Rickert Drive Naperville, IL 60540 630-355-6400 Medical Supply Plus Nucara 1982 Grant Street 800-606-4332 101 W. Vallette St Hobart, IN 46342 219-949-7587 Elmhurst, IL 60126 630-834-1223 Vyto’s Pharmacy Shield Healthcare - Mail order or pick up 6949 Kennedy Avenue 747 Church Road Hammond, IN 46323 219-845-2900 Elmhurst, IL 60126 800-675-8847 ILLINOIS area code 309 area code 708 Central Illinois Medical Equipment Doubek Pharmacy 203 East Locust Street 11350 S Cicero Bloomington, IL 61701 309-827-3459 Alsip, IL 60803 708-293-1122 Gottlieb Pharmacy 675 W North Avenue Melrose Park, IL 60160 708-450-4941 Johnson’s Drugs area code 312 1914 Ridge Road Homewood, IL 60430 708-957-7676 Carnegi Sargent Pharmacy Vandenberg Med Tech 760 Water Tower Place - 845 N Michigan, Suite 902 6813 W 167 th Street Chicago, IL 60611 312-280-1220 Tinley Park, IL 60477 708-532-7050 area code 618 Byrd Watson Drug Co. -

2011 Indiana Utility Regulatory Commission

Report to the Regulatory Flexibility Committee of the Indiana General Assembly 2011 Indiana Utility Regulatory Commission EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Indiana Utility Regulatory Commission’s (Commission or IURC) Report to the Regulatory Flexibility Committee of the Indiana General Assembly for 2011 highlights key issues addressed by the Commission with respect to the Electric, Natural Gas, Water/Wastewater, and Communications utilities in the state of Indiana. This year’s report provides an overview of recent issues; considers the current industry landscape; and discusses the successes, as well as the challenges facing the utility industry. In order to better serve the Legislature, the agency focused on issues thought to be most relevant based on inquiries received and legislation filed in recent years. Additionally, information was streamlined to make the report more readable and user-friendly; hopefully you will agree. We understand this is an important tool for the General Assembly and are committed to providing information in a manner useful for policymaking and responding to constituent inquiries. If there are any questions about the information contained herein, the Commission welcomes the opportunity to further discuss those matters of concern. For your convenience, a list of acronyms and a glossary are included. - Electricity - In 2010, Indiana’s retail rates were 13th lowest in the nation, as compared to 15th lowest in 2009. Consequently, Indiana’s average retail prices for electricity have been and are presently competitive both nationally and regionally. Retail prices are the average price for all rate classes, including residential, commercial, and industrial customers. Neighboring states’ total customer retail rates for 2010 rank as follows, with the first being the lowest: Kentucky 6th, Ohio 28th, Illinois 36th, and Michigan 33rd. -

Evaluation; Appendix H5 and H6 Index

West Lake Corridor Final Environmental Impact Statement/ Record of Decision and Section 4(f) Evaluation Appendix H5 Appendix H5. Index of General Public Written Comments, Response to General Public Comments March 2018 H5-1 West Lake Corridor Final Environmental Impact Statement/ Record of Decision and Section 4(f) Evaluation Appendix H5 This page is intentionally left blank. March 2018 H5-2 West Lake Corridor Final Environmental Impact Statement/ Record of Decision and Section 4(f) Evaluation Appendix H5 Table H5-1: General Public Written Comments and Responses Index Last Name First Name Comment ID(s) Albrecht Ronald 40 Albright Brandon 41 Albright Nicole 42 Alderden Aaron 43 Alesi Amanda 44 Alexander Deb 45 Allegrezza William 46 Alrick Ron 47 Amezcua Manuel 48 Amezcua Samantha 49 Andrzejewski Edward 50 Anitec Barbara 51 Applesies Edith 52 Armstrong LJ 53 Ashrita 54 Astor Debbie 55 Astor Debbie 56 Babcock Don 57 Babusiak Kate 58 Babusiak Kevin 59 Bachmann Debbie 60 Baker Dean 61 Bakker Gene 62 Bakker Patricia 63 Barrett Gabrielle 64 Barrett Laura 65A – 65G Barrett Michael 66 Barrientez Monica 67 Baum Kathryn 68 Benchik Jon 69 March 2018 H5-3 West Lake Corridor Final Environmental Impact Statement/ Record of Decision and Section 4(f) Evaluation Appendix H5 Last Name First Name Comment ID(s) Bernardi Connie 70 Bonchnowski Ann 71 Boer Debi 72 Bolling April 73 Bowers Judy 74 Brandenburg Carly 75 Brandenburg Carly and Steve 76 Bravo Heriberto 77 Brennan Jennifer 78 Brewe Ian 79 Brohart Rodney 80 Buchnat Ursula 81 Budeselich Michelle 82 Burbach Brian 83 - 85 Burbridge Wende 86 Burgos Mercedes 87 Burian Amy 88 Byrne Mary and Rich 89 Byrne Mary 90 Cable Chris 91 Cannon Margaret 92 Carlson Rich 93 Casas M.