2011 Indiana Utility Regulatory Commission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Milebymile.Com Personal Road Trip Guide Indiana United States Highway #41

MileByMile.com Personal Road Trip Guide Indiana United States Highway #41 Miles ITEM SUMMARY 0.0 Indiana/Kentucky State Indiana/Kentucky State Line, South of Evansville, Indiana, near the Line Bridge over Ohio River, crosses United States Highway #41 into Indiana from Kentucky and starts its northerly journey in Indiana mostly parallel to the Indiana/Illinois. This Highway enters Illinois on the north just north of Hammond, Indiana, ending its long run through Indiana. Altitude: 387 feet 2.7 Washington Ave: Medical Altitude: 381 feet Center 3.2 Lincoln Avenue : Lincoln Avenue, The University of Evansville, a small, private University university located in Evansville, Indiana, The University of Evansville is nationally renowned for its Theatre and Physical Therapy departments, Islamic Center of Evansville, Grace & Peace Lutheran Church, Evansville State Hospital, Indiana Mental Health Center, Altitude: 384 feet 3.5 Interchange State Rte #62 : Altitude: 390 feet Evansville, IN 4.0 Oak Hill St./Virginia St. : Oak Hill Street/Virginia Street, Deaconnes Hospital, a two-campus Park & Zoo healthcare in Evansville, Indiana, Lamasco Park, Helfrich Park, Mesker Music Theater, The Mesker Park Zoo and Botanic Garden, one of the oldest and largest zoos in Indiana, located in Evansville, Indiana, Community of Hilltop, Community of Western Terrace, located in Evansville, Indiana. Altitude: 390 feet 5.3 Interchange State Rte Interchange State Route #66/Diamond Avenue Expressway, to Mesker #66/Diamond Ave Expy : Park, Mesker Zoo located within Helfrich Park in Evansville, Indiana, Mesker Park Garvin Park, Bosse Field, a baseball stadium built in 1915, Stringtown Branch Library, Evansville Country Club, Community of Diamond Stringtown, Community of Willemette, Skylane Airport, an airport located along State Route #66 west off United States Highway #41. -

206 Kappa Phi 1.Pdf

A PETITION TO THE INTERNATIONAL FRATERNITY OF DELTA SIGMA PI BY KAPPA BETA ALPHA PROFESSIONAL BUSINESS FRATERNITY VALPARAISO UNIVERSITY VALPARAISO,, INDIANA 'Valparaiso University ^ ^ College of Business Administration Office of the Dean Valparaiso, Indiana 46383 February 22,1983 International Fraternity of Delta Sigma Pi c/o Mark Roberts 330 South Campus Avenue Oxford, OH 1^5056 Gentlemens We, the brothers of Kappa Beta Alpha, a Professional Business Fraternity at Valparaiso University, submit for your consideration this petition for acceptance. Our group was formed by students in the College of Business Administration who hoped to broaden their scope through professional programs. With this idea we hope to better our campus and the community of Valparaiso Surrounding it. We set our standards high, as does Delta Sigma Pi, and are constantly working to meet them. The honor of being accepted as a charter of Delta Sigma Pi woui^l be of mutual benefit to all concerned. We would promote the values and high standards of Delta Sigma Pi, and in turn Delta Sigma Pi could enable us to reach more people inside and outside our coramiinity. Therefore, we ask that you grant Kappa Beta Alpha a charter so that we may establish a chapter of the International Fratemity of Delta Sigma Pi on the Valparaiso University campus. Respectfully, The Brothers of Kappa BetaAlpha dAyujJd ^naicMuiu'^ /Ul^f-'O-^-r^ (^ta. Jk<^AA:6U LETTERS OF RECOMMENDATION Valparaiso University 5? College of Business Administration Valparaiso, Indiana Office of tfie Dean 46383 December 28, 1982 Mr. Mark Roberts Director of Chapter Operations Delta Sigma Pi 330 South Campus Avenue P.O. -

Advisory Committee Civil Rules

ADVISORY COMMITTEE 7K ON CIVIL RULES WASHINGTON, D.C. MAY 3-5, 1993 L L I17 l lV H H H H I X K I ~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ | F, LI I7 I~~~~~~ H H El, Li 7 S-- LE Tentative Agenda Meeting of Advisory Committee on Civil Rules Federal Judiciary Building Washington, DC May 3-5, 1993 I. Welcome of new members; Orientation. II. Report on status of pending amendments. If Supreme Court returns any amendments for further consideration, we'll 7 probably take these up at this point.) III. Revisiting proposals previously considered. Ed Cooper will be sending out separately to each member his latest work on these. He has received various comments and suggestions from the groups and individuals to whom he sent drafts on an informal basis. Rule 23 tF. Rule 26(c) (sunshine/confidentiality) Rule 43 7 Rule 68 (also possible FJC study) L Rule 83 Rule 84 t IV. Style Revision. Enjoy yourself. V. New Matters. We have received a variety of suggestions for changes. We'll need to discuss them briefly to decide which we might want to go forward with. I'm asking Ed and John Rabiej to go through their correspondence to make a list. Among the items I'm aware of: Rules 7 and 11 (signature requirement for electronic filing); Rule 45 (expansion of trial subpoena jurisdiction); Rules 52 and 59 (requirement for 10- day filing--not merely serving); Rule 53 (expansion of role of Master to discovery/pretrial areas); Rule 64 (ABA proposal--legislative action). VI. Plans for future meetings, submissions to Standing Committee, etc. -

2009 Registration Document

2009 REGISTRATION DOCUMENT WorldReginfo - 88364e60-83e1-4e25-beba-ac6c76609afa In this registration document, the terms “EDF Energies Nouvelles” and the “Company” refer to EDF Energies Nouvelles SA. The “Group” refers to the group comprising the Company and all of its subsidiaries. This registration document includes forward-looking statements and information about the objectives of the Group, in particular, relating to its projects in progress. These statements are sometimes identifi ed by the use of the future or conditional tense, as well as terms such as “estimate”, “believe”, “have the objective of”, “intend to”, “expect”, “result in”, “should” and other similar expressions. It should be noted that the realisation of these objectives and forward-looking statements is dependent on the circumstances and facts that arise in the future. The forward-looking statements and information about the objectives may be affected by known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors that may signifi cantly alter the future results, performance and accomplishments planned or expected by the Company. These factors may include changes in the economic and commercial situation, regulations and the risk factors described in Chapter 4 of the registration document. Investors are invited to read carefully the risk factors included in Chapter 4 of this registration document before making a decision on whether to invest in the Company. The occurrence of one or more of these risks may adversely affect the Group’s business, fi nancial position or results of operations, or on its ability to achieve its objectives. A change in the method used to consolidate wind farms in the United States took place during the fi nancial year ended on 31 December 2009. -

GADS Wind Turbine Generation Data Reporting Instructions

GGAADDSS WWiinndd TTuurrbbiinnee GGeenneerraattiioonn Data Reporting Instructions Effective January 2010 Version 1.1.0 Table of Contents Table of Contents Section 1 – Introduction ............................................................................................................... 7 Who Must Report .................................................................................................................... 7 Terms, Definitions, and Equations.......................................................................................... 7 Data Release Guidelines ......................................................................................................... 8 Talk to Us ................................................................................................................................ 8 Section 2 – Data Transmittal and Format .................................................................................. 9 Transmittal .............................................................................................................................. 9 Format ..................................................................................................................................... 9 Wind Generation Data Entry Software ................................................................................. 10 Questions and Comments ..................................................................................................... 10 Section 3 – Plants, Groups, and Sub-Groups .......................................................................... -

To Download This Report (PDF)

2009 INDIANA RENEWABLE ENERGY RESOURCES STUDY State Utility Forecasting Group Energy Center Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana David Nderitu Emily Gall Douglas Gotham Forrest Holland Marco Velastegui Paul Preckel September 2009 2009 Indiana Renewable Energy Resources Study - State Utility Forecasting Group Table of Contents Page List of Figures iii List of Tables v Acronyms and Abbreviations vi Foreword ix 1. Overview 1 1.1 Trends in renewable energy consumption in the United States 1 1.2 Trends in renewable energy consumption in Indiana 4 1.3 References 8 2. Energy from Wind 9 2.1 Introduction 9 2.2 Economics of wind energy 11 2.3 State of wind energy nationally 14 2.4 Wind energy in Indiana 18 2.5 Incentives for wind energy 24 2.6 References 26 3. Dedicated Energy Crops 27 3.1 Introduction 27 3.2 Economics of energy crops 30 3.3 State of energy crops nationally 32 3.4 Energy crops in Indiana 36 3.5 Incentives for energy crops 38 3.6 References 40 4. Organic Waste Biomass 43 4.1 Introduction 43 4.2 Economics of organic waste biomass 46 4.3 State of organic waste biomass nationally 47 4.4 Organic waste biomass in Indiana 49 4.5 Incentives for organic waste biomass 53 4.6 References 54 i 2009 Indiana Renewable Energy Resources Study - State Utility Forecasting Group 5. Solar Energy 57 5.1 Introduction 57 5.2 Economics of solar technologies 60 5.3 State of solar energy nationally 60 5.4 Solar energy in Indiana 66 5.5 Incentives for solar energy 66 5.6 References 69 6. -

Reg Flex Cover.Indd

Indiana Utility Regulatory Commission Regulatory Flexibility Report to the Indiana General Assembly '08 Tradition. Innovation. Change. Executive Summary EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Indiana Utility Regulatory Commission (Commission) is pleased to present its 2008 Report to the Regulatory Flexibility Committee of the Indiana General Assembly. This Report highlights key issues that confront Indiana Electric, Natural Gas, Communications and Water/Wastewater utility industries and discusses the role of the Commission in managing these issues. Over the course of the last year, many topics have been addressed including: energy efficiency, aging infrastructure, the rising cost of energy, access to broadband and economic development. The Commission has been monitoring statewide and national efforts to address these issues in addition to remaining at the forefront of discussion with legislators, other state regulators and commissions. The Report broaches many of these topics and provides updates on how they affect Indiana. While each industry has unique concerns, several discussed in this Report are common to more than one type of industry. This Executive Summary contains a brief overview of these cross-industry and industry-specific issues, which are more fully addressed in the body of the Report. By examining cross-industry concerns, certain trends emerge along with areas that may need more attention. Plus, they demonstrate how similar utilities are with regard to regulation and support. The Report contains, as an appendix, a copy of the External Client Survey undertaken by the Commission in 2007. Even though the results of the Survey were very positive, the Commission provided a response that addressed the issues identified in the Survey and continues to explore and undertake efforts to enhance overall performance. -

Of 65 NIRPC ADA PUBLIC HEARING 6/11/13 CART & Transcription

Page 1 of 65 1 NIRPC ADA PUBLIC HEARING 2 PURDUE CALUMET LIBRARY 3 HAMMOND, IN 4 JUNE 11, 2013 5 1-4 p.m. 6 7 8 CART SERVICES AND VERBATIM TRANSCRIPTION SERVICES 9 PROVIDED BY: 10 VOICE TO PRINT CAPTIONING, LLC 11 9800 Connecticut Drive 12 Crown Point, IN 46307 13 219-644-3220 14 www.voicetoprint.com 15 [email protected] 16 NIRPC ADA PUBLIC HEARING 6/11/13 CART & Transcription by Voice to Print Captioning Page 2 of 65 17 >> GAIL BARKER: Hello. My name is Gail Barker, the 18 Disability Coordinator at Purdue North Central. I will be 19 serving as the facilitator of this year's public hearing for the 20 Northwestern Indiana Regional Planning Commission. I would like 21 to welcome those who are here at Purdue University Calumet for 22 our 2013 public hearing. I would also like to welcome those 23 that are watching on the Internet and those that are watching 24 from the site at LaPorte, Indiana also on the Internet. 25 NIRPC, as the agency is called, is a Metropolitan Planning 26 Organization that is responsible for regional transportation 27 planning in Lake, Porter and LaPorte Counties. 28 This hearing is being held as a result of a Class Action 29 ADA transportation lawsuit which was filed in 1997. ADA stands 30 for the Americans with Disabilities Act, which was enacted into 31 law in 1990. The lawsuit settlement, which was reached in 2006, 32 requires NIRPC to have an independent ADA review each year of 33 all its subgrantees; that is, all the public transit providers 34 for whom NIRPC provides monitoring and oversight. -

East Chicago Junior Police: an Effective Project in the Non-Academic Area of the School's Total Educational Attack on the Disadvantagement of Youth

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 053 241 UD 011 713 TITLE East Chicago Junior Police: An Effective Project in the Non-Academic Area of the School's Total Educational Attack on the Disadvantagement of Youth. INSTITUTION East Chicago City School District, Ind: PUB DATE Dec 70 NOTE 65p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS After School Programs, Behavior Problems, Child Development, *Delinquency Prevention, *Disadvantaged Youth, Health Activities, Music Activities, *Police School Relationship, Program Descriptions, Program Design, Program Effectiveness, Program Evaluation, School Community Programs, Volunteers, Youth Clubs, Youth Problems, *Youth Programs IDENTIFIERS *East Chicago Junior Police, Elementary Secondary Education Title I, Indiana ABSTRACT The Junior Police program utilized non-academic youth interests as its foundation. The project filled the need for a youth organization, a youth clearinghouse, and more aid to delinquent and predelinquent youth to redirect them into ways of thinking and acting beneficial both to themselves and to the community. The objectives of the program were to provide supplemental effort in attacking conditions which interfere with a child's educational growth--those conditions, being underachievement, social, cultural, and nutritional disadvantagement, and health deficiencies. Program areas included were music, arts and crafts, sports, health, cosmetology, business, hobbies, field trips, and parties. Both professionals and volunteers comprised the staff including members of the East Chicago police and fire departments. Those working with the program submit that the Junior Police members have been involved in fewer incidents of delinquency than non-members. (Author/CB) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT fiAS BEEN REPRO- OUCED EXACTLY /.S RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG- INATING IT. -

October 9, 2018 INDIANA UTILITY REGULATORY COMMISSION

STATE OF INDIANA INDIANA UTILITY REGULATORY COMMISSION VERIFIED PETITION OF NORTHERN ) INDIANA PUBLIC SERVICE COMPANY LLC ) FOR (1) APPROVAL OF AN ADJUSTMENT ) TO ITS ELECTRIC SERVICE RATES ) THROUGH ITS TRANSMISSION, ) DISTRIBUTION, AND STORAGE SYSTEM ) IMPROVEMENT CHARGE (“TDSIC”) RATE ) SCHEDULE; (2) AUTHORITY TO DEFER 20% ) CAUSE NO. 44733‐TDSIC‐4 OF THE APPROVED CAPITAL ) EXPENDITURES AND TDSIC COSTS FOR ) RECOVERY IN PETITIONER’S NEXT ) GENERAL RATE CASE; (3) APPROVAL OF ) PETITIONER’S UPDATED 7‐YEAR ) ELECTRIC PLAN, INCLUDING ACTUAL ) AND PROPOSED ESTIMATED CAPITAL ) EXPENDITURES AND TDSIC COSTS THAT ) EXCEED THE APPROVED AMOUNTS IN ) CAUSE NO. 44733‐TDSIC‐3, ALL PURSUANT ) TO IND. CODE § 8‐1‐39‐9; AND (4) ) APPROVAL OF PETITIONER’S RETURN OF ) EXCESS INCOME TAX REVENUE ) RECOVERED THROUGH ITS BASE RATES ) BETWEEN JANUARY 1 AND APRIL 30, 2018 ) THROUGH ITS TDSIC FACTOR. ) PETITIONER’S NOTICE OF SUBSTITUTION OF WITNESS Northern Indiana Public Service Company LLC, by counsel, hereby gives notice that Charles A. Vamos is being substituted for and is adopting the direct testimony and attachments previously prefiled by James E. Zucal. For purposes of convenience, attached hereto are (1) a redline version of the Introduction section of Mr. Vamos’ direct testimony showing the changes from the previously prefiled version of Mr. Zucal’s direct testimony, and (2) a clean copy of Mr. Vamos’ direct testimony. At the evidentiary hearing in this Cause, the clean version of Mr. Vamos’ direct testimony (along with the attachments) will be offered -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 112 164 CE 004 982 TITLE Indiana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 112 164 CE 004 982 TITLE Indiana Career Resource Center: Annual Report: 1974-75. INSTITUTION Indiana Univ., South Bend. Indiana Career Resource Center. PUB DATE [75] NOTE 207p.; Portions of Appendix N may not be completely legible in microfiche; Not available in hard copy due to paper color of original document EDRS PRICE LIF-$0.76 Plus Postage. HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Annual Reports; *Career Education; Educational Development; *Educational Programs; Educational Resources; Letters (Correspondence); Questionnaires; *Resource Centers; Resource Materials; Teaching Techniques IDENTIFIERS Career Information Centers; *Indiana ABSTRACT The report presents an account of the activities and progress of the Indiana Career Resource Center in its sixth year as a source of ideas and programs for educators developing their own career education programs. It documents the services offered: (1) inservice and preservice training of classroom teachers, student teachers, counselors, administrators, and school board and community members in the concepts and involvement of a career education program;(2) editing and producing media to assist educators, including a career education specialty training directory; (3) developing contacts in the local community and becoming involved with local projects as a means of piloting ideas that could be duplicated in other settings (women's career center, career guidance institute, life planning, conference telephone use in career education) and career development workshops for the Comprehensive -

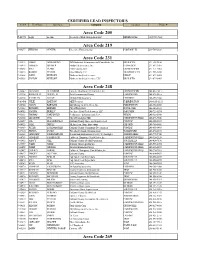

Area Code 205 Area Code 219 Area Code 231 Area

CERTIFIED LEAD INSPECTOR'S Cert # First Name Last Name Company Location Phone # Area Code 205 P-01571 Leigh Lachine Accelerated Risk Management LLC BIRMINGHAM (205)533-7662 Area Code 219 P-04277 WILLIAM CENTER Greentree Environmental PORTAGE, IN 219-764-2828 Area Code 231 P-01412 JAMES ARMSTRONG ARM Industrial & Environmental Consultants, Inc. BIG RAPIDS 231-592-9858 P-06974 HAROLD BROWER Norlund & Associates, Inc. LUDINGTON 231-843-3485 P-06268 KYLE CLARK PM Environmental GRAND RAPIDS 231-571-3082 P-00013 ROBERT PETERS Otwell Mawby P.C. TRAVERSE CITY 231-946-5200 P-01268 JOHN REHKOPF Northern Analytical Services LEROY 231-679-0005 P-05558 JUSTON REHKOPF Northern Analytical Services, LLC BIG RAPIDS 231-679-0005 Area Code 248 P-06647 ALI SALIH AL-HADDAD Fisbeck, Thompson, Carr & Huber, Inc. GRAND RAPIDS 248-410-7411 P-02334 ROOSEVELT AUSTIN, III Arch Environmental Group FARMINGTON 248-426-0165 P-06124 KATHLEEN BALAZE McDowell & Associates FERNDALE 248-399-2066 P-03480 JULIE BARTON AKT Peerless FARMINGTON 248-615-1333 P-04724 JASON BARYLSKI IAQ Management Services, Inc. FARMINGTON 248-932-8800 P-01082 RICHARD BREMER City of Royal Oak ROYAL OAK 248-246-3133 P-04983 JOSEPH BURLEY Freelance Envir-Tech Services, LLC OAK PARK 248-721-8574 P-05333 THOMAS CARPENTER Performance Environmental Serv. WIXOM 248-926-3800 P-06860 LEE EDWIN COX City of Farmington Hills FARMINGTON HILLS 248-473-9546 P-00657 JOE DEL MORONE II Oakland County Home and Improvement PONTIAC 248-858-5307 P-04823 JANE DIPPLE All American Home Inspections OXFORD 248-760-5441 P-00869 PETER ESSENMACHER Oakland County Community Development PONTIAC 248-858-0493 P-07010 DONNA EVANS Waterford Schools Transportation WATERFORD 248-674-2692 P-06262 GREGORY FAHRENBRUCH Restoration Environmental Safety Technologies AUBURN HILLS 248-778-5940 P-04763 JENNIFER FASHBAUGH Fishbeck, Thmpson, Carr & Huber, Inc.