Advisory Committee Civil Rules

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ed 035 852 Edrs Price Descriptors Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 035 852 AC 006,443 TITLE OFF-CAMPUS STUDY CENTERS FOP FEDERALEMPLOYEES, FISCAL YEAR 1969. INSTITUTION CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION, WASHINGTON,D.C. BUREAU OF TRAINING. PUB DATE JAN 70 NOTE 146P.; REVISED EDITION EDRS PRICE EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$7.40 DESCRIPTORS ADMISSION CRITERIA, AGENCIES, COLLEGES,COURSES, *DIRECTORIES, *EDUCATIONAL FACILITIES,*EMPLOYEES, *FEDERAL GOVERNMENT, GEOGRAPHIC REGIONS,*OFF CAMPUS FACILITIES, UNITS OF STUDY (SUBJECT FIELDS) , UNIVERSITIES, UNIVERSITY EXTENSION ABSTRACT ONE OF THREE MAJOR TRAINING AND EDUCATIONALRESOURCE PUBLICATIONS FROM THE CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION,THIS DIRECTORY PROVIDES INFORMATION' ON INDIVIDUAL OFF CAMPUSSTUDY CENTERS FOR FEDERAL EMPLOYEES. NUMBERS OF CENTERS ANDPARTICIPANTS ARE TABULATED, BY AGENCY AND BY STAIE OR OTHER GEOGRAPHICLOCATION. COOPERATING INSTITUTIONS, PROGRAMS OR COURSE OFFERINGS,ELIGIBILITY FOR ATTENDANCE, GENERAL ITEMS OF INTEREST, ANDSOURCES OF FURTHER INFORMATION ARE INDICATED FOR THE CIVIL SERVICECOMMISSION'S FEDERAL AFTER-HOURS EDUCATION PROGRAM; FIVE DEPARTMENTOF COMMERCE CENTERS; 77 DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE CENTERS (ARMY, NAVY, AIR.FORCE, AND THE NATIONAL SECURITY AGENCY); FIVE UNDER THEDEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION, AND WELFARE; SIX UNDER THE DEPARTMENTOF JUSTICE; SIX UNDER THE NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACEADMINISTRATION; EIGHT UNDER THE POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT; FIVE UNDERTHE VETERANS ADMINISTRATION; AND ONE CENTER EACH UNDER THE DISTRICTOF COLUMBIA GOVERNMENT, THE GENERAL ACCOUNTING OFFICE, AND THE DEPARTMENTOF THE INTERIOR. ADDRESSES AND TELEPHONE NUMBERS ARE GIVENFOR THE TEN REGIONAL CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION TRAINING CENTERS. INDEXESOF LOCATIONS, EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS, AND SUBJECT AREASARE INCLUDED. (LY) U S DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT POINTS Of VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. -

206 Kappa Phi 1.Pdf

A PETITION TO THE INTERNATIONAL FRATERNITY OF DELTA SIGMA PI BY KAPPA BETA ALPHA PROFESSIONAL BUSINESS FRATERNITY VALPARAISO UNIVERSITY VALPARAISO,, INDIANA 'Valparaiso University ^ ^ College of Business Administration Office of the Dean Valparaiso, Indiana 46383 February 22,1983 International Fraternity of Delta Sigma Pi c/o Mark Roberts 330 South Campus Avenue Oxford, OH 1^5056 Gentlemens We, the brothers of Kappa Beta Alpha, a Professional Business Fraternity at Valparaiso University, submit for your consideration this petition for acceptance. Our group was formed by students in the College of Business Administration who hoped to broaden their scope through professional programs. With this idea we hope to better our campus and the community of Valparaiso Surrounding it. We set our standards high, as does Delta Sigma Pi, and are constantly working to meet them. The honor of being accepted as a charter of Delta Sigma Pi woui^l be of mutual benefit to all concerned. We would promote the values and high standards of Delta Sigma Pi, and in turn Delta Sigma Pi could enable us to reach more people inside and outside our coramiinity. Therefore, we ask that you grant Kappa Beta Alpha a charter so that we may establish a chapter of the International Fratemity of Delta Sigma Pi on the Valparaiso University campus. Respectfully, The Brothers of Kappa BetaAlpha dAyujJd ^naicMuiu'^ /Ul^f-'O-^-r^ (^ta. Jk<^AA:6U LETTERS OF RECOMMENDATION Valparaiso University 5? College of Business Administration Valparaiso, Indiana Office of tfie Dean 46383 December 28, 1982 Mr. Mark Roberts Director of Chapter Operations Delta Sigma Pi 330 South Campus Avenue P.O. -

Morehead State University 1994 Eagle Football

~.......,, .., ~ , h -·- ,· ~·a Stczte LC~i'l7ersity -. - - I ' , I ii, I I I I . ' l 1994 Ohio Valley Conference Composite Schedule September 1 September 24 October 29 Kentucky State @ Southeast Missouri Tennessee Tech @ Morehead State Ala.-Birmingham @ Morehead State Kentucky Wesleyan @ Austin Peay Tennessee State@ South Carolina Scace Jacksonville Scare @ Middle Tennessee Tennessee-Martin @ Southeast Missouri Austin Peay @ Southeast Missouri Murray Scace @ Eastern Illinois Eastern Kentucky @ Austin Peay Tennessee Tech@ Murray Scare Lock Haven@ Tennessee Tech Middle Tennessee@ Murray State Eastern Kentucky@ T ennessee-Marcin Eastern Kentucky@ Western Kentucky October 1 November 5 September 3 Southeast Missouri @ Morehead State Southeast Missouri @ Eastern Kentucky Tennessee-Marcin@ Southern Illinois Austin Peay@ Tennessee Tech Murray State @ Morehead State Florida A&M @ Tennessee State Middle Tennessee @ T ennessee Scace T ennessee Scace @ Tennessee Tech Eastern Kentucky@ Middle Tennessee Middle Tennessee@ Austin Peay Morehead State @ Marshall Tennessee-Marcin@ Murray State C harleston Southern@ Tennessee-Martin September 10 October 8 November 12 Southeast Missouri @ Tennessee Tech Middle Tennessee@ James Madison Austin Peay @ Samford Tennessee-Martin@ Middle T ennessee Tennessee Tech @ Marshall Morehead State@ Tennessee-Martin Tennessee State @ Eastern Kentucky Samford @ Eastern Kentucky Tennessee Seate@ Murray State Murray Scace @ Austin Peay East Tennessee@ Morehead State Illinois State@ Middle Tennessee October 15 Southeast Missouri -

Country and City Codes

We hope this information will be useful to you in your travels! The information is believed to be reliable and up to date as of the time of publication. However, no warranties are made as to its reliability or accuracy. Check with Full Service Network Customer Service or your operator for official information before you travel. Country and City Codes Afghanistan country code: 93 Albania country code: 355 city codes: Durres 52, Elbassan 545, Korce 824, Shkoder 224 Algeria country code: 213 city codes: Adrar 7, Ain Defla 3, Bejaia 5, Guerrar 9 American Samoa country code: 684 city codes: City codes not required. All points 7 digits. Andorra country code: 376 city codes: City codes not required. All points 6 digits. Angola country code: 244 Anguilla country code: 264 Antarctica Casey Base country code: 672 Antarctica Scott Base country code: 672 Antigua (including Barbuda) country code: 268 city codes: City codes not required. * Footnote: You should not dial the 011 prefix when calling this country from North America. Use the country code just like an Area Code in the U.S. Argentina country code: 54 city codes: Azul 281, Bahia Blanca 91, Buenos Aires 11, Chilvilcoy 341, Comodoro Rivadavia 967, Cordoba 51, Corrientes 783, La Plata 21, Las Flores 224, Mar Del Plata 23, Mendoza 61, Merio 220, Moreno 228, Posadas 752, Resistencia 722, Rio Cuarto 586, Rosario 41, San Juan 64, San Rafael 627, Santa Fe 42, Tandil 293, Villa Maria 531 Armenia country code: 374 city codes: City codes not required. Aruba country code: 297 city codes: All points 8 plus 5 digits The Ascension Islands country code: 247 city codes: City codes not required. -

Year Ended June 30, 2016

COUNTY OF PRINCE GEORGE, VIRGINIA COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 201 COUNTY OF PRINCE GEORGE,VIRGINIA COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 2016 Prepared By: Prince George County Finance Department i COUNTY OF PRINCE GEORGE, VIRGINIA COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTORY SECTION Title Page i Table of Contents iii-vi Principal Officials vii Organizational Chart ix Certificate of Achievement xi Letter of Transmittal xiii-xvi FINANCIAL SECTION Independent Auditors’ Report 1-3 Management’s Discussion and Analysis 5-12 Basic Financial Statements Government-wide Financial Statements: Exhibit 1 Statement of Net Position 17 Exhibit 2 Statement of Activities 18-19 Fund Financial Statements: Exhibit 3 Balance Sheet–Governmental Funds 23 Exhibit 4 Reconciliation of the Balance Sheet of Governmental Funds to the Statement of Net Position 24 Exhibit 5 Statement of Revenues, Expenditures and Changes in Fund Balances–Governmental Funds 25 Exhibit 6 Reconciliation of the Statement of Revenues, Expenditures and Changes in Fund Balances of Governmental Funds to the Statement of Activities 26 Exhibit 7 Statement of Net Position–Proprietary Funds 27 Exhibit 8 Statement of Revenues, Expenses and Changes in Net Position–Proprietary Funds 28 iii COUNTY OF PRINCE GEORGE, VIRGINIA COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS (CONTINUED) Page FINANCIAL SECTION:(CONTINUED) Basic Financial -

Northern Neck

Rappahannock Record, Kilmarnock, VA September 4, 2008 • C1 Northern Neck www.rrecord.com REGULAR CLASSIFIED RATES: Up to 25 words: 1 week-$6; 2 weeks-$10; 3 weeks-$15; 4 weeks-$18; 4-week minimum run for TFN ads. 5 weeks-$22.50; 6 weeks-$27; 7 weeks-$31.50; 8 weeks-$36. $40 for 13 weeks. $.24 per word for ads over 25 words. Personals, Card of Thanks, In Memoriam, Yard Sales, and Work Wanted ads must be paid in advance. 10 percent discount for cash, non-refundable. CUSTOM CLASSIFIED RATES: $1.25 per line (9-line minumum) for Legals, Notices, Resolu- tions, Memorial and other custom classi eds. 24/7 Exposure! All classi eds in this section also appear weekly on the Rappahannock Record web pages at www.rrecord.com. You can add a color photo linked to your classi ed for only $25 for up to 13 weeks. Classi ed deadline: Noon Tuesday. Display ad deadline: 5 p.m. Monday. Call 804-435-1701 or 1-800-435-1701 Real Estate Real Estate Real Estate Real Estate $950,000: MAGNIFICENT 6.7ACs on ****Port & Starboard R.E., Inc.**** *3.6 ACRES on TAYLORS CREEK *CARTERS CREEK Lot: Rare oppor- Mosquito Creek, just off Rappahan- 100s of N’Neck properties for sale! in Weems. Approximately 700ft of tunity to build your dream home on .99 nock River, minutes to Bay on Windmill 804-529-5555 or 804-334-8045 waterfront w/pier. Former seafood acres of beautiful waterfront property! Point Rd. 3BR/2BA home w/3ft. water, www.port-starboard.com business. -

Of 65 NIRPC ADA PUBLIC HEARING 6/11/13 CART & Transcription

Page 1 of 65 1 NIRPC ADA PUBLIC HEARING 2 PURDUE CALUMET LIBRARY 3 HAMMOND, IN 4 JUNE 11, 2013 5 1-4 p.m. 6 7 8 CART SERVICES AND VERBATIM TRANSCRIPTION SERVICES 9 PROVIDED BY: 10 VOICE TO PRINT CAPTIONING, LLC 11 9800 Connecticut Drive 12 Crown Point, IN 46307 13 219-644-3220 14 www.voicetoprint.com 15 [email protected] 16 NIRPC ADA PUBLIC HEARING 6/11/13 CART & Transcription by Voice to Print Captioning Page 2 of 65 17 >> GAIL BARKER: Hello. My name is Gail Barker, the 18 Disability Coordinator at Purdue North Central. I will be 19 serving as the facilitator of this year's public hearing for the 20 Northwestern Indiana Regional Planning Commission. I would like 21 to welcome those who are here at Purdue University Calumet for 22 our 2013 public hearing. I would also like to welcome those 23 that are watching on the Internet and those that are watching 24 from the site at LaPorte, Indiana also on the Internet. 25 NIRPC, as the agency is called, is a Metropolitan Planning 26 Organization that is responsible for regional transportation 27 planning in Lake, Porter and LaPorte Counties. 28 This hearing is being held as a result of a Class Action 29 ADA transportation lawsuit which was filed in 1997. ADA stands 30 for the Americans with Disabilities Act, which was enacted into 31 law in 1990. The lawsuit settlement, which was reached in 2006, 32 requires NIRPC to have an independent ADA review each year of 33 all its subgrantees; that is, all the public transit providers 34 for whom NIRPC provides monitoring and oversight. -

Perry Park, KY 40363 (502) 484-2159

CASE NUMBER:/ GLENWOOD HALL GOLF & COUNTRY CLUB P.O. BOX 147 Perry Park, KY 40363 (502) 484-2159 PERRY PARK RESORT, INC. & PERRY PARK RESIDENT OWNER'S Assoc P.O. BOX 147 PERRY PARK, KY 40363 DATE 1248197 TE S Net 30 -. ._ . .. DESCRIPTION RATE AMOUNT PERRY PARK RESORT, INC. & PERRY PARK RESIDENT OWNER ASSOCIATION 388.00 388.00 INVOICE FOR: PROPERTY OWNER'S PRO-RATA CONTRIBUTION TO ESCROW ACCOUNT FOR CARROLL COWWATER DISTRICT PARTICIPATION. Total $3388.00 \ .. .. ., .;. ,". ' .. ..... .. PERRY PARK RESORT, INC. FAX: (502) 484-2467 i GLENWOOD HALL GOLF & COUNTRY CLUB A- P.O. BOX 147 Perry Park, KY 40363 \---I -----"I PERRY PARK RESORT, INC. 62 PERRY PARK RESIDENT OWNER'S ASSOC P.O. BOX 147 PERRY PARK, KY 40363 DATE 45 SPRINGPORT RD P.O. BOX 116 PERRY PARK, KY 40363 TERMS PASTDUE -4 DESCRIPTION RATE ERRY PARK RESORT, INC. &PERRY PARK RESIDENT OWNER ASSOClATION 388.00 WOKE FOR: 388.00 ROPERTY OWNER'S PRO-RATA CONTRIBUTION TO ESCROW ACCOUNT \ 3R CARROLL COUNTY WATER DISRICT PARTICIPATION. --- Total s388.00 ... .... -< . .*. ...I ^.. .. ... I PERRY PARK RESORT, INC. FAX: (502) 484-2467.. Ju 1 20 99 04:17p Par-Tee LLC PERRY PARK &SORT (hNERSASSOCWN p.0. Box 112 PERRY PARK#KY 40363 September03, 1998 Mr. Jim Berling PARTEE UC c/o Berling Engindg 1671 Park Road, Suile 1 Ft. Wright, KY 41011 A meeting was held an Saturday, August 29.1998 between yourself andMark Stibert of PAR-lEE UC& Bin Blick, Nancy Ralermann and myself of Perry Park Resort Owncn Associatian hc. (PPROA). Discusion inchxkd the adminimtion of the joint escrow account related to the CarrOn Carnty Water Distrkt (CCWD) coIIstmction project You indicated at the meeting that Curt Moberg, General Manager afFmyPark Fbon Inc. -

East Chicago Junior Police: an Effective Project in the Non-Academic Area of the School's Total Educational Attack on the Disadvantagement of Youth

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 053 241 UD 011 713 TITLE East Chicago Junior Police: An Effective Project in the Non-Academic Area of the School's Total Educational Attack on the Disadvantagement of Youth. INSTITUTION East Chicago City School District, Ind: PUB DATE Dec 70 NOTE 65p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS After School Programs, Behavior Problems, Child Development, *Delinquency Prevention, *Disadvantaged Youth, Health Activities, Music Activities, *Police School Relationship, Program Descriptions, Program Design, Program Effectiveness, Program Evaluation, School Community Programs, Volunteers, Youth Clubs, Youth Problems, *Youth Programs IDENTIFIERS *East Chicago Junior Police, Elementary Secondary Education Title I, Indiana ABSTRACT The Junior Police program utilized non-academic youth interests as its foundation. The project filled the need for a youth organization, a youth clearinghouse, and more aid to delinquent and predelinquent youth to redirect them into ways of thinking and acting beneficial both to themselves and to the community. The objectives of the program were to provide supplemental effort in attacking conditions which interfere with a child's educational growth--those conditions, being underachievement, social, cultural, and nutritional disadvantagement, and health deficiencies. Program areas included were music, arts and crafts, sports, health, cosmetology, business, hobbies, field trips, and parties. Both professionals and volunteers comprised the staff including members of the East Chicago police and fire departments. Those working with the program submit that the Junior Police members have been involved in fewer incidents of delinquency than non-members. (Author/CB) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT fiAS BEEN REPRO- OUCED EXACTLY /.S RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG- INATING IT. -

Securities and Exchange Commission

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D. C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Date of report (Date of earliest event reported): June 1, 1998 ASHLAND INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Kentucky (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation) 1-2918 61-0122250 (Commission File Number) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 1000 Ashland Drive, Russell, Kentucky 41169 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) P.O. Box 391, Ashland, Kentucky 41114 (Mailing Address) (Zip Code) Registrant's telephone number, including area code (606) 329-3333 Item 5. Other Events On June 1, 1998, Arch Coal, Inc. (Arch Coal) announced that it had completed the acquisition of Atlantic Richfield Company's (ARCO) domestic coal operations for approximately $1.14 billion. The transaction will be financed entirely with debt using new credit facilities. Completion of the transaction creates a new joint venture called Arch Western Resources, LLC (Arch Western Resources), owned 99% by Arch Coal and 1% by ARCO. Arch Western Resources will account for all of Arch Coal's operating activity west of the Mississippi River. The Registrant owns approximately 55% of Arch Coal's issued and outstanding shares. The foregoing summary of the attached press release is qualified in its entirely by the complete text of such document, a copy of which is attached hereto. Item 7. Financial Statements and Exhibits (c) Exhibits 99.1 Press Release dated June 1, 1998. SIGNATURES Pursuant to the requirements of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, the registrant has duly caused this report to be signed on its behalf by the undersigned thereunto duly authorized. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 112 164 CE 004 982 TITLE Indiana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 112 164 CE 004 982 TITLE Indiana Career Resource Center: Annual Report: 1974-75. INSTITUTION Indiana Univ., South Bend. Indiana Career Resource Center. PUB DATE [75] NOTE 207p.; Portions of Appendix N may not be completely legible in microfiche; Not available in hard copy due to paper color of original document EDRS PRICE LIF-$0.76 Plus Postage. HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Annual Reports; *Career Education; Educational Development; *Educational Programs; Educational Resources; Letters (Correspondence); Questionnaires; *Resource Centers; Resource Materials; Teaching Techniques IDENTIFIERS Career Information Centers; *Indiana ABSTRACT The report presents an account of the activities and progress of the Indiana Career Resource Center in its sixth year as a source of ideas and programs for educators developing their own career education programs. It documents the services offered: (1) inservice and preservice training of classroom teachers, student teachers, counselors, administrators, and school board and community members in the concepts and involvement of a career education program;(2) editing and producing media to assist educators, including a career education specialty training directory; (3) developing contacts in the local community and becoming involved with local projects as a means of piloting ideas that could be duplicated in other settings (women's career center, career guidance institute, life planning, conference telephone use in career education) and career development workshops for the Comprehensive -

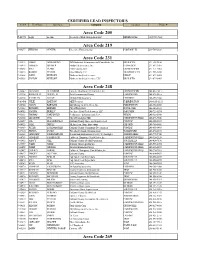

Area Code 205 Area Code 219 Area Code 231 Area

CERTIFIED LEAD INSPECTOR'S Cert # First Name Last Name Company Location Phone # Area Code 205 P-01571 Leigh Lachine Accelerated Risk Management LLC BIRMINGHAM (205)533-7662 Area Code 219 P-04277 WILLIAM CENTER Greentree Environmental PORTAGE, IN 219-764-2828 Area Code 231 P-01412 JAMES ARMSTRONG ARM Industrial & Environmental Consultants, Inc. BIG RAPIDS 231-592-9858 P-06974 HAROLD BROWER Norlund & Associates, Inc. LUDINGTON 231-843-3485 P-06268 KYLE CLARK PM Environmental GRAND RAPIDS 231-571-3082 P-00013 ROBERT PETERS Otwell Mawby P.C. TRAVERSE CITY 231-946-5200 P-01268 JOHN REHKOPF Northern Analytical Services LEROY 231-679-0005 P-05558 JUSTON REHKOPF Northern Analytical Services, LLC BIG RAPIDS 231-679-0005 Area Code 248 P-06647 ALI SALIH AL-HADDAD Fisbeck, Thompson, Carr & Huber, Inc. GRAND RAPIDS 248-410-7411 P-02334 ROOSEVELT AUSTIN, III Arch Environmental Group FARMINGTON 248-426-0165 P-06124 KATHLEEN BALAZE McDowell & Associates FERNDALE 248-399-2066 P-03480 JULIE BARTON AKT Peerless FARMINGTON 248-615-1333 P-04724 JASON BARYLSKI IAQ Management Services, Inc. FARMINGTON 248-932-8800 P-01082 RICHARD BREMER City of Royal Oak ROYAL OAK 248-246-3133 P-04983 JOSEPH BURLEY Freelance Envir-Tech Services, LLC OAK PARK 248-721-8574 P-05333 THOMAS CARPENTER Performance Environmental Serv. WIXOM 248-926-3800 P-06860 LEE EDWIN COX City of Farmington Hills FARMINGTON HILLS 248-473-9546 P-00657 JOE DEL MORONE II Oakland County Home and Improvement PONTIAC 248-858-5307 P-04823 JANE DIPPLE All American Home Inspections OXFORD 248-760-5441 P-00869 PETER ESSENMACHER Oakland County Community Development PONTIAC 248-858-0493 P-07010 DONNA EVANS Waterford Schools Transportation WATERFORD 248-674-2692 P-06262 GREGORY FAHRENBRUCH Restoration Environmental Safety Technologies AUBURN HILLS 248-778-5940 P-04763 JENNIFER FASHBAUGH Fishbeck, Thmpson, Carr & Huber, Inc.