Transformation of Traditional Wooden Log Houses in Modern Latvia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Personal Names and Denomination of Livonians in Early Written Sources

ESUKA – JEFUL 2014, 5–1: 13–26 PERSONAL NAMES AND DENOMINATION OF LIVONIANS IN EARLY WRITTEN SOURCES Enn Ernits Estonian University of Life Sciences Abstract. This paper presents the timeline of ethnonyms denoting Livonians; specifies their chronology; and analyses the names used for this ethnos and possible personal names. If we consider the dating of the event, the earliest sources mentioning Livonians are Gesta Danorum and the Tale of Bygone Years (both 10th century), but both sources present rather dubious information: in the first the battle of Bråvalla itself or the date are dubious (6th, 8th or 10th century); in the latter we cannot be sure that the member of the Rus delegation was really a Livonian. If we consider the time of recording, the earliest sources are two rune inscriptions from Sweden (11th century), and the next is the list of neighbouring peoples of the Russians from the Tale of Bygone Years (12th century). The personal names Bicco and Ger referred in Gesta Danorum, and Либи Аръфастовъ in Tale of Bygone Years are very problematic. The first certain personal name of a Livonian is *Mustakka, *Mustukka or *Mustoikka (from Finnic *musta ‘black’) written in 1040–1050s on a strip of birch bark in Novgorod. Keywords: Livs, Finnic peoples, ethnonyms, anthroponyms, onomastics DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12697/jeful.2014.5.1.01 1. Introduction This paper (1) seeks to present the timeline of ethnonyms denoting Livonians; (2) to specify their chronology; (3) and to analyse the names used for this ethnos and possible personal names. It is supple- mental to the paper by Mauno Koski on words denoting Livonians (Koski 2011). -

Crusading, the Military Orders, and Sacred Landscapes in the Baltic, 13Th – 14Th Centuries ______

TERRA MATRIS: CRUSADING, THE MILITARY ORDERS, AND SACRED LANDSCAPES IN THE BALTIC, 13TH – 14TH CENTURIES ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the School of History, Archaeology and Religion Cardiff University ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in History & Welsh History (2018) ____________________________________ by Gregory Leighton Abstract Crusading and the military orders have, at their roots, a strong focus on place, namely the Holy Land and the shrines associated with the life of Christ on Earth. Both concepts spread to other frontiers in Europe (notably Spain and the Baltic) in a very quick fashion. Therefore, this thesis investigates the ways that this focus on place and landscape changed over time, when crusading and the military orders emerged in the Baltic region, a land with no Christian holy places. Taking this fact as a point of departure, the following thesis focuses on the crusades to the Baltic Sea Region during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. It considers the role of the military orders in the region (primarily the Order of the Teutonic Knights), and how their participation in the conversion-led crusading missions there helped to shape a distinct perception of the Baltic region as a new sacred (i.e. Christian) landscape. Structured around four chapters, the thesis discusses the emergence of a new sacred landscape thematically. Following an overview of the military orders and the role of sacred landscpaes in their ideology, and an overview of the historiographical debates on the Baltic crusades, it addresses the paganism of the landscape in the written sources predating the crusades, in addition to the narrative, legal, and visual evidence of the crusade period (Chapter 1). -

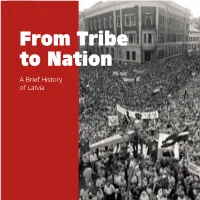

From Tribe to Nation a Brief History of Latvia

From Tribe to Nation A Brief History of Latvia 1 Cover photo: Popular People of Latvia are very proud of their history. It demonstration on is a history of the birth and development of the Dome Square, 1989 idea of an independent nation, and a consequent struggle to attain it, maintain it, and renew it. Above: A Zeppelin above Rīga in 1930 Albeit important, Latvian history is not entirely unique. The changes which swept through the ter- Below: Participants ritory of Latvia over the last two dozen centuries of the XXV Nationwide were tied to the ever changing map of Europe, Song and Dance and the shifting balance of power. From the Viking Celebration in 2013 conquests and German Crusades, to the recent World Wars, the territory of Latvia, strategically lo- cated on the Baltic Sea between the Scandinavian region and Russia, was very much part of these events, and shared their impact especially closely with its Baltic neighbours. What is unique and also attests to the importance of history in Latvia today, is how the growth and development of a nation, initially as a mere idea, permeated all these events through the centuries up to Latvian independence in 1918. In this brief history of Latvia you can read how Latvia grew from tribe to nation, how its history intertwined with changes throughout Europe, and how through them, or perhaps despite them, Lat- via came to be a country with such a proud and distinct national identity 2 1 3 Incredible Historical Landmarks Left: People of The Baltic Way – this was one of the most crea- Latvia united in the tive non-violent protest activities in history. -

Were the Baltic Lands a Small, Underdeveloped Province in a Far

3 Were the Baltic lands a small, underdeveloped province in a far corner of Europe, to which Germans, Swedes, Poles, and Russians brought religion, culture, and well-being and where no prerequisites for independence existed? Thus far the world extends, and this is the truth. Tacitus of the Baltic Lands He works like a Negro on a plantation or a Latvian for a German. Dostoyevsky The proto-Balts or early Baltic peoples began to arrive on the shores of the Baltic Sea nearly 4,000 years ago. At their greatest extent, they occupied an area some six times as large as that of the present Baltic peoples. Two thousand years ago, the Roman Tacitus wrote about the Aesti tribe on the shores of the #BMUJDBDDPSEJOHUPIJN JUTNFNCFSTHBUIFSFEBNCFSBOEXFSFOPUBTMB[ZBT many other peoples.1 In the area that presently is Latvia, grain was already cultivated around 3800 B.C.2 Archeologists say that agriculture did not reach southern Finland, only some 300 kilometers away, until the year 2500 B.C. About 900 AD Balts began establishing tribal realms. “Latvians” (there was no such nation yet) were a loose grouping of tribes or cultures governed by kings: Couronians (Kurshi), Latgallians, Selonians and Semigallians. The area which is known as -BUWJBUPEBZXBTBMTPPDDVQJFECZB'JOOP6HSJDUSJCF UIF-JWT XIPHSBEVBMMZ merged with the Balts. The peoples were further commingled in the wars which Estonian and Latvian tribes waged with one another for centuries.3 66 Backward and Undeveloped? To judge by findings at grave sites, the ancient inhabitants in the area of Latvia were a prosperous people, tall in build. -

Prisoners of War in the Baltic in the XII-XIII Centuries

Prisoners of war in the Baltic in the XII-XIII centuries Kurt Villads Jensen* University of Stockholm Abstract Warfare was cruel along the religious borders in the Baltic in the twelfth and thirteenth century and oscillated between mass killing and mass enslavement. Prisoners of war were often problematic to control and guard, but they were also of huge economic importance. Some were used in production, some were ransomed, some held as hostages, all depending upon status of the prisoners and needs of the slave owners. Key words Warfare, prisoners of war. Baltic studies. Baltic crusades. Slavery. Religious warfare. Medieval genocide. Resumen La guerra fue una actividad cruel en las fronteras religiosas bálticas entre los siglos XII y XIII, que osciló entre la masacre y la esclavitud en masa. El control y guarda de los prisioneros de guerra era frecuentemente problemático, pero también tenían una gran importancia económica. Algunos eran empleados en actividades productivas, algunos eran rescatados y otros eran mantenidos como rehenes, todo ello dependiendo del estatus del prisionero y de las necesidades de sus propietarios. Palabras clave Guerra, prisioneros de guerra, estudios bálticos, cruzadas bálticas, esclavitud, guerra de religión, genocidio medieval. * Dr. Phil. Catedrático. Center for Medieval Studies, Stockholm University, Department of History, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected] http://www.journal-estrategica.com/ E-STRATÉGICA, 1, 2017 • ISSN 2530-9951, pp. 285-295 285 KURT VILLADS JENSEN If you were living in Scandinavia and around the Baltic Sea in the high Middle Ages, you had a fair change of being involved in warfare or affected by war, and there was a considerable risk that you would be taken prisoner. -

Read Transcript

History of the Crusades. Episode 237. The Baltic Crusades. The Livonian Crusade Part XXX. The Southern Push Part 2. Hello again. Last week we started off by noting that the Teutonic Order wished to establish a land link between their territory in Livonia and their territory in Prussia, which pretty much entailed conquering the lands currently located between Prussia and Livonia, which were: Semigallia, Kurland and Samogitia. However we got sidetracked by other goings on in the surrounding regions. We saw King Valdemar II’s son, King Eric, struggle to make Denmark great again. We saw Pope Innocent IV appoint Albert Suerbeer to the position of Archbishop of Prussia. We saw William of Modena be rewarded for his years of service as the Church’s Mister Fix-it, as he rose to the position of Cardinal-Bishop of Sabina, and we saw Dietrich von Gruningen replace Hermann Balk as the Master of the Teutonic Order in Livonia. Right, so now we are all set to examine the push south by the Teutonic Order in Livonia through the lands of the pagans. The new Master of the Teutonic Order in Livonia, Dietrich von Gruningen, had done a pretty good job of both motivating the members of the Teutonic Order in Livonia, and of establishing ties between the Order and members of the local Church hierarchy. As a result the Bishops of Riga, Osel and Dorpat voiced their support for the push south by the Order, and provided both men and financial assistance. Due to this support by the local Church hierarchy, a fairly impressive force of Christians, including Letts and Livonians, mustered alongside Knights from the Teutonic Order in Riga. -

The Clash Between Pagans and Christians: the Baltic Crusades from 1147-1309

The Clash between Pagans and Christians: The Baltic Crusades from 1147-1309 Honors Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors research distinction in History in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Donald R. Shumaker The Ohio State University May 2014 Project Advisor: Professor Heather J. Tanner, Department of History 1 The Baltic Crusades started during the Second Crusade (1147-1149), but continued into the fifteenth century. Unlike the crusades in the Holy Lands, the Baltic Crusades were implemented in order to combat the pagan tribes in the Baltic. These crusades were generally conducted by German and Danish nobles (with occasional assistance from Sweden) instead of contingents from England and France. Although the Baltic Crusades occurred in many different countries and over several centuries, they occurred as a result of common root causes. For the purpose of this study, I will be focusing on the northern crusades between 1147 and 1309. In 1309 the Teutonic Order, the monastic order that led these crusades, moved their headquarters from Venice, where the Order focused on reclaiming the Holy Lands, to Marienberg, which was on the frontier of the Baltic Crusades. This signified a change in the importance of the Baltic Crusades and the motivations of the crusaders. The Baltic Crusades became the main theater of the Teutonic Order and local crusaders, and many of the causes for going on a crusade changed at this time due to this new focus. Prior to the year 1310 the Baltic Crusades occurred for several reasons. A changing knightly ethos combined with heightened religious zeal and the evolution of institutional and ideological changes in just warfare and forced conversions were crucial in the development of the Baltic Crusades. -

Couronians | Semigallians | Selonians

BALTS’ ROAD, THE COURONIAN ROUTE SEGMENT Route: Rucava – Liepāja – Grobiņa – Jūrkalne – Alsunga – Kuldīga – Ventspils – Talsi – Valdemārpils – Sabile – Saldus – Embūte – Mosėdis – Plateliai – Kretinga – Klaipėda – Palanga – Rucava Duration: 3–4 days. Length about 790 km In ancient times, Couronians lived on the coast of the Baltic Sea. At that time, the sea and rivers were an important waterway that inuenced their way of life and interaction with neighbouring nations. You will nd out about this by taking the circular Couronian Route Segment. Peaceful deals were made during trading. Merchants from faraway lands Macaitis, Tērvete Tourism Information Centre, Zemgale Planning Region. Planning Zemgale Centre, Information Tourism Tērvete Macaitis, were tempted to visit the shores of the Baltic Sea looking for the northern gold – Photos: Līva Dāvidsone, Artis Gustovskis, Arvydas Gurkšnis, Denisas Nikitenka, Mindaugas Mindaugas Nikitenka, Denisas Gurkšnis, Arvydas Gustovskis, Artis Dāvidsone, Līva Photos: Publisher: Kurzeme Planning Region, Zemgale Planning Region 2019 Region Planning Zemgale Region, Planning Kurzeme Publisher: amber. To nd out more about amber, visit the Palanga Amber Museum (40) Centre, National Regional Development Agency in Lithuania. in Agency Development Regional National Centre, and the Liepāja Crafts House (6). Ancient Couronian boats, the barges, are Authors: Kurzeme Planning Region, Zemgale Planning Region, Šiauliai Tourism Information Information Tourism Šiauliai Region, Planning Zemgale Region, Planning Kurzeme Authors: -

Conquest, Conversion, and Heathen Customs in Henry of Livonia's

ashgate.com ashgate.com © Copyrighted material ashgate.com Conquest, Conversion, and Heathen Customs in Henry of Livonia’s Chronicon Livoniae ashgate.com and the Livländische Reimchronik Shami Ghosh ashgate.com Magdalen College, Oxford [email protected] 1 Henry of Livonia’s Chronicon Livoniae (HCL), a narrative of theashgate.com mission to Livonia2 between the last decades of the twelfth century and ca. 1227 (when Henry wrote), and the Livländische Reimchronik (LR),3 covering Baltic history until ca. 1290 (when the chronicle was probably composed), are the sole contemporary, locally written narrative works for the history of this region during this period. ashgate.com Henry’s chronicle was composed within the first generation of conversion, while the authority of the bishop of Riga was still dominant, and before the Teutonic ashgate.com A version of this paper was presented to the Medieval German Seminar at the University of Oxford on 1 December 2010, and I am very grateful to the members of the seminar for their feedback. I should also like to thank Michael Gervers at the University of Toronto for discussing some of this material with me many years ago; the two anonymous readers of this journal for their comments; and Helen Buchanan at the Taylor Institution Library for her efforts in ashgate.comobtaining otherwise unavailable scholarship for me. 1 Heinrici Chronicon Livoniae, ed. Leonid Arbusow and Albert Bauer, MGH SRG 31, 2nd ed. (Hanover, 1955), cited as HCL by page and line numbers. All translations are my own. On Henry’s life and the background to and date of his chronicle, see Vilis Biļķins, “Die Autoren der Kreuzzugszeit und das Milieu Livlands und Preussens,” Acta Baltica 14 (1974), 231–54; James A. -

Latvia 100 Snapshot Stories

This is your personal invitation to a cultural adventure of Latvia – a country in Northern Europe, by the Baltic Sea, celebrating its Centenary of statehood in 2018. One hundred years, one hundred stories – snapshots of the codes of our consciousness, values and virtues, a glimpse at both the changeable and the constant Latvia, a reflection of the zeitgeist. Just like any other nation, we have our unforgettable experiences and past traumas, which we strive to overcome, big and small victories that keep inspiring us and keep reminding us of the things worth fighting for, special people and landmarks as important symbols telling the story of who we are, our weaknesses and strengths, and our future ambitions. The ingredients that make a nation are often the same, but their endless combinations are what make each and every nation unique and beautiful. Just like in the story about Latgalian pottery – we are all different, yet made of the same substance. Let us explore, inspire, support and celebrate each other, because we are all connected. We are all one. Contents WHITE THE BIRTH SCENTS SINGING DOES SIZE MATTER? Page 7 Page 37 Page 59 Page 93 Page 113 The Dainas / Pagans / Local heroes. Francis The Latvian childhood / Dancing / The Song and Rīga. Bigger on the inside / The Lielvārde sash / Signs Trasūns / Local heroes. Tadenava / Kids on the Dance Celebration / A stage for excellence / and symbols / Ancestral Zigfrīds Anna Meierovics / move / The Talka / Birch Distant Light / The Useful connections / Fertile spirits / Ley lines / The The Satversme / Money / sap / Beauty tips / Beer / Melancholic Waltz / soil for new ideas / Looking Baltic Sea / Wood / The War of Independence / The When in doubt, use dill / Symbolism / Contemporary above and beyond / plait / The flower wreath / Freedom Monument / Pork The wooden house / art / Poetic documentary / The Cosmos / Peaceful Bar codes / Rye bread / and butter / Rīga Central Gardening / Mushrooming / Theatre / Alberta Street in coexistence / The next 100 The Baltic tribes / The Market / Another war. -

The Story of an Unrealised Common Celebration

LITHUANIAN HISTORICAL STUDIES 24 2020 ISSN 1392-2343 PP. 109–142 https://doi.org/10.30965/25386565-02401005 THE STORY OF AN UNREALISED COMMON CELEBRATION: HOW LATVIA AND LITHUANIA PLANNED TO MARK THE 700TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE BATTLE OF SAULE Dangiras Mačiulis, (Lithuanian Institute of History) Mārtiņš Mintaurs (University of Latvia) ABSTRACT The Battle of Saule took place on 22 September 1236 in the Šiauliai area in Lithuania, at which the Lithuanians crushed the army of the Livonian Order that had launched a crusade to their lands from Riga. The Brothers of the Sword who tried to return to Riga via Semigallia (Zemgale) were harried and killed by the Semigallians, a Baltic tribe that became part of the Latvian and Lithuanian nations which formed later on. The date of the Battle of Saule has been marked in Lithuania and Latvia since 22 September 2000, by decrees of the parliaments of the two countries, as the Day of Baltic Unity, with the aim of reminding Lith- uanians and Latvians of their ethnic similarities, and to encourage the closeness of the two kindred nations and the Lithuanian and Latvian states. The first time Lithuania and Latvia intended to commemorate the Battle of Saule together was in 1936, the 700th anniversary of the battle. However, the attempt to organise a shared celebration of the anniversary of the battle failed. This article seeks to answer the following questions: what prompted Latvia and Lithuania to organise the commemoration of the Battle of Saule in 1936; what were the meanings that accompanied the imagery of the Battle of Saule at the time; and why did the joint anniversary celebration not take place? KEYWORDS: the Battle of Saule, nationalism of Lithuanians, nationalism of Lat- vians, history of politics, collective memory The Battle of Saule took place on 22 September 1236 in the Šiau- liai area, when the Lithuanians crushed the army of the Livonian Brothers of the Sword Order (Fratres militæ Christi Livoniæ) that had launched a crusade to their lands from Riga. -

12Th Century AD Specific Burial Practices and Artefact Forms Serve To

ENG Ancient Peoples in the Territory of Latvia 1st –12th century AD Specific burial practices and artefact forms serve to distinguish several different archaeological cultures, connected with the ancestors of the Couronians [64–65]*, Latgalians, Selonians and Semigallians [61], and Finnic groups [62,63]. In the Middle Iron Age (400–800 AD) and the first half of the Late Iron Age (800–1 000 AD), the archaeological cultures of the Early Iron Age underwent complicated processes of ethno-cultural change, developing into the Baltic peoples (Couronians, Semigallians, Latgallians and Selonians) and Finnic peoples (Livs, Estonians and Vends) that we know from written sources. In the second half of the Late Iron Age (1 000–1 200 AD) the distinctive culture of Latvia’s indigenous peoples reached its highest point of development. The dead were buried together with a wide range of grave goods. Specific peoples’ territory of residence can be traced by characteristic burial traditions, various forms of ornaments, tools and weapons. The Couronians [66–70] lived along the Baltic littoral of western Latvia and western Lithuania. The Latgallians and Selonians [71–78] inhabited eastern Latvia, the Selonians lived along the left bank of the Daugava and in north-eastern Lithuania, while the Semigallians [79–82] lived in the basin of the River Lielupe, in southern Latvia and northern Lithuania. In the 10th and 11th century in the lower reaches of Daugava and Gauja developed and flourished the culture of the Livs. [83,84]. By the River Ālande, in the Couronian area, a Scandinavian colony existed for two centuries (650–800 AD) [85,86].