Marathi Postpositions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ED132833.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 132 833 FL 008 225 AUTHOR Johnson, Dora E.; And Others TITLE Languages of South Asia. A Survey of Materials for the Study of the Uncommonly Taught Languages. INSTITUTION Center for Applied Linguistics, Arlington, Va. SPONS AGENCY Office of Education (DHEW), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 76 CONTRACT 300-75-0201 NOTE 52p. AVAILABLE FROMCenter for Applied Linguistics, 1611 North Kent Street, Arlington, Virginia 22209 ($3.95 each fascicle: complete set of 8, $26.50) BDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$3.50 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Education; Afro Asiatic Languages; *Annotated Bibliographies; Bengali; Dialect Studies; Dictionaries; *Dravidian Languages; Gujarati; Hindi; Ind° European Languages; Instructional Materials; Kannada; Kashmiri; Language Instruction; Language Variation; Malayalam; Marathi; Nepali; Panjabi; Reading Materials; Singhalese; Sino Tibetan Languages; Tamil; Telugu; *Uncommonly Taught Languages; Urdu IDENTIFIERS Angami Naga; Ao Naga; Apatani; Assamese; Bangru; Bhili; Bhojpuri; Boro; Brahui; Chakesang Naga; Chepang; Chhatisgarhi; Dafla; Galiong; Garo; Gondi; Gorum; Gurung; Hindustani; *Indo Aryan Languages; Jirel; Juang; Kabui Naga; Kanauri; Khaling; Kham; Kharia; Kolami; Konda; Korku; Kui; Kumauni; Kurukh; Ruwi; Lahnda; Maithili; Mundari Ho; Oraon; Oriya; Parenga; Parji; Pashai; Pengo; Remo; Santali; Shina; Sindhi; Sora; *Tibet° Burman Languages; Tulu ABSTRACT This is an annotated bibliography of basic tools of access for the study_of the uncommonly taught languages of South Asia. It is one of eight fascicles which constitute a revision of "A Provisional Survey of Materials for the Study of the Neglected Languages" (CAI 1969). The emphasis is on materials for the adult learner whose native language is English. Languages are grouped according to the following classifications: Indo-Aryan; Dravidian; Munda; Tibeto-Burman; Mon-Khmer; Burushaski. -

Inflection Rules for English to Marathi Translation

Available Online at www.ijcsmc.com International Journal of Computer Science and Mobile Computing A Monthly Journal of Computer Science and Information Technology ISSN 2320–088X IJCSMC, Vol. 2, Issue. 4, April 2013, pg.7 – 18 RESEARCH ARTICLE Inflection Rules for English to Marathi Translation Charugatra Tidke 1, Shital Binayakya 2, Shivani Patil 3, Rekha Sugandhi 4 1,2,3,4 Computer Engineering Department, University Of Pune, MIT College of Engineering, Pune-38, India [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract— Machine Translation is one of the central areas of focus of Natural Language Processing where translation is done from Source Language to Target Language preserving the meaning of the sentence. Large amount of research is being done in this field. However, research in Machine Translation remains highly localized to the particular source and target languages due to the large variations in the syntactical construction of languages. Inflection is an important part to get the correct translation. Inflection is basically the adding of appropriate suffix to the word according to the sentence structure to obtain the meaningful form of the word. This paper presents the implementation of the Inflection for English to Marathi Translation. The inflection of Nouns, Pronouns, Verbs, Adjectives are done on the basis of the other words and their attributes in the sentence. This paper gives the rules for inflecting the above Parts-of-Speech. Key Terms: - Natural Language Processing; Machine Translation; Parsing; Marathi; Parts-Of-Speech; Inflection; Vibhakti; Prataya; Adpositions; Preposition; Postposition; Penn Tags I. INTRODUCTION Machine translation, an integral part of Natural Language Processing, is important for breaking the language barrier and facilitating the inter-lingual communication. -

Sage's Mission

SAGE’S MISSION SAGE’S MISSION English Version of TWENTY ‘GULAB VATIKA’ BOOKLETS Life Mission of Saint Gulabrao Maharaj Translated By Vasant Joshi Published by Vasant Joshi SAGE’S MISSION SAGE’S MISSION English Version of TWENTY ‘GULAB VATIKA’ BOOKLETS Life Mission of Saint Gulabrao Maharaj * Self Published by: Vasant Joshi English Translator: © Vasant Joshi B-8, Sarasnagar, Siddhivinayak Society, Shukrawar Peth, Pune 411021. Mobile.: +91-9422024655 | Email : [email protected] * All rights reserved with English Translator No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the English Translator. * Typesetting and Formatting Books and Beyond Mrs Ujwala Marne New Ahire Gaon, Warje, Pune. Mobile. : +91-8805412827 / 7058084127 | Email: [email protected] * Cover Design by : Aadity Ingawale * First Edition : 21st March 2021 * Price : ₹ 500/- SAGE’S MISSION DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF MY WIFE LATE VRINDA JOSHI yG y SAGE’S MISSION INDEX Subject Page No. � Part I I to XVIII Prologue of English Translator by Vasant Joshi II Babaji Maharaj Pandit III Life Graph IV Life Mission VIII Literature Treasure Trove XII � Part II 1 to 1. Acquaintance (By K. M. Ghatate) 3 2. Merit Honour (By Renowned Persons) 43 3. Babajimaharaj Pandit (By V. N. Pandit) 73 4. Friendship Devotion (By Vasudeorao Mule) 95 5. Mankarnika Mother (By Milind Tripurwar) 110 6. Swami Bechirananda (By Milind Tripurwar) 126 7. Autobiography (By Self) 134 8. Saint’s Departure (By Self) 144 9. -

Maharashtra Census 2011 Pdf in Marathi

Maharashtra census 2011 pdf in marathi Continue The state of Maharashtra is located in the western part of India. Maha means large and rastra means state in Hindi and covers an area of 307,713 square kilometers (118,809 sq mi). Maharashtra's population in 2020 is estimated at 123 million people (12.3 crores), according to the unique identity of Aadhar India, updated on May 31, 2020, by mid-2020 the population is expected to be 123,144,223, India's second most democratic state after Uttar Pradesh, 9% of the Indian population lives in Maharatrash. Mumbai is the financial capital and financial capital of India and the most popular city with 20 million people in 2019. It has a long coastline stretching nearly 720 km along the Arabian Sea to the west, Goa and Karnataka to the south, Chhattisgarh and Telangana to the east. Maharashtra is the most economically developed country in India with a GDP value of USD 390 million in 2018-2019, sharing about 15%. Its per head is $2500. According to the 2016 Niti Aayog report, the total birth rate is 1.8. Photo Source: Maharashtrians In traditional dress welcoming Gudi Padwa, the bike rally in Mumbai Maharashtra is the third urbanized state among other states since before independence. According to the 1901 population survey, 19 million people were recorded in the state. The average population growth was 24.81 in the fifty years following the Indian population survey from 1951 to 2001. Population growth slowed to 15.99% in 2011 while that was 22.73% compared to 2001. -

Marathi Style Guide

Marathi Style Guide Published: December, 2017 Microsoft Marathi Style Guide Table of Contents 1 About this style guide ......................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Recommended style references .............................................................................................. 4 2 Microsoft voice ...................................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Choices that reflect Microsoft voice ...................................................................................... 5 2.1.1 Word choice ........................................................................................................................... 6 2.1.2 Words and phrases to avoid ............................................................................................ 7 2.1.3 Transliteration ........................................................................................................................ 9 2.2 Sample Microsoft voice text ..................................................................................................... 9 2.2.1 Address the user to take action ...................................................................................... 9 2.2.2 Promote a feature .............................................................................................................. 10 2.2.3 Provide how-to guidelines ............................................................................................. -

The Languages of South Asia

THE LANGUAGES OF SOUTH ASIA a catalogue of rare books: dictionaries, grammars, manuals, & literature. with several important works on Tibetan Catalogue 31 John Randall (Books of Asia) John Randall (Books of Asia) [email protected] +44 (0)20 7636 2216 www.booksofasia.com VAT Number : GB 245 9117 54 Cover illustration taken from no. 4 (Colebrooke) in this catalogue; inside cover illustrations taken from no. 206 (Williams). © John Randall (Books of Asia) 2017 THE LANGUAGES OF SOUTH ASIA Catalogue 31 John Randall (Books of Asia) INTRODUCTION The conversion of the East India Company from trading concern to regional power South Asia, home to six distinct linguistic gave further impetus to the study of South families, remains one of the most Asian languages. Employees of the linguistically complex regions on earth. Company were charged with producing According to the 2001 Census of India, linguistic guides for official purposes. 1,721 languages and dialects were spoken as Military officers needed language skills to mother tongues. Of these, 29 had one issue commands to locally recruited troops. million or more speakers, and a further 31 And as the Company sought to perpetuate more than 100,000. the Mughal system of rule, knowledge of Persian as well as regional languages was The political implications of such dizzying essential for revenue collectors and diversity have been no less complex. Since administrators of justice. 1953, there have been many attempts to re- divide the country along linguistic lines. As All the while, some independent European recently as 2014, the new state of Telangana scholars demonstrated a genuine interest in was created as a homeland for Telugu and empathy for South Asian languages and speakers. -

![[Journal of the Simplified Spelling Society, 11, 1989/2 P1 in the Printed Version]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0501/journal-of-the-simplified-spelling-society-11-1989-2-p1-in-the-printed-version-4220501.webp)

[Journal of the Simplified Spelling Society, 11, 1989/2 P1 in the Printed Version]

[Journal of the Simplified Spelling Society, 11, 1989/2 p1 in the printed version] Journal of the Simplified Spelling Society, 11, 1989/2 Contents Editorial. Correspondence. Inaugural presidential address: Donald G Scragg. English Spelling and its Reform: some observations from a historical perspective. From around the world Asmah Haji Omar. The Malay Spelling Reform. Susan Baddeley. Progress of the Spelling Reform Debate in France. Upward/Augst/IdS. Recent Developments in 'Re-regulating' Written German. Madhukar N Gogate. Progress with Roman Lipi in India. Vacancy for Secretary to the Simplified Spelling Society George C Bischoff. Romanian-English Orthographical Anecdote. Articles, Debate, Report, Research Visual Disruption from Letter-Omission. David Stark. 2-The Principle of Minimal Interference. Anon. Strategies of an Adult Dyslexic. Edgar Gregerson & Christopher Upward discuss Morfemes and Cut Spelling. Appeal for data on alternative spellings and misspellings by 6 to 11 year olds. Valerie Yule. Experimental Versions of Cut Spelling - CS1 and CS2. Robert Craig. Towards an International Orthografy, or Planning the World Language. Submission from the SSS and the UK i.t.a. Federation to the National Curriculum Council. Miscellany. Journal backnumbers; Lindgren cartoon; Brown & Brown. Publications; items received; Conference; Meetings of the Society. Permission to reproduce material from this Journal should be obtained from the Editor and the source acknowledged. Material for the 1989 No.3 issue should reach the editor by 1 November 1989. [Journal of the Simplified Spelling Society, 11, 1989-2 p2 in the printed version] The Society Founded in 1908, the Simplified Spelling Society has included among its officers: Daniel Jones, Horace King, Gilbert Murray, William Temple, H G Wells, Sir James Pitman, A C Gimson and John Downing. -

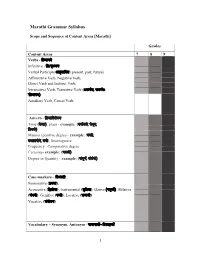

Marathi Grammar Syllabus Verbs

Marathi Grammar Syllabus Scope and Sequence of Content Areas [Marathi] Grades Content Areas 7 8 9 Verbs - ik`xyaapado Infinitive - ik`.xmaULr}pa Verbal Participle QaataUsaaiQata (present, past, future) Affirmative Verb, Negative Verb, Direct Verb and Indirect Verb, Intransitive Verb, Transitive Verb (Akxma_kx, sakxma_k xik`xyaapad) Auxiliary Verb, Causal Verb Adverb - ik`xyaaivaSaoYaNa Time (koxvha) , place - example: (vagaa_kxDo, yaoqaUna, itakxDo) Manner (positive degree - example: (kxSaI, kxSaata%honao, kxsaoo), Interrogative, Frequency, Comparative degree Certainty- example: (naWkxI) Degree or Quantity - example: (saMpaUNa_, qaaoDosao) Case-markers – ivaBaWtaI Nominative (pa`qamaa), Accusative (iÓtaIyaa), Instrumental (taRitayaa), Dative (catauqaI_), Ablative (paMcamaI), Genitive (YaYzI), Locative (saptamaI) Vocative (saMbaaoQana) Vocabulary – Synonym, Antonym - samaanaaqaI_-ivar]ÔaqaI_ 1 Singular – Plural - ek vacana – Anaok vacana Gender: Masculine – pauilaMga Feminine s~aIilaMga Neuter napauMsak ilaMga Adjective ivaSaoYaNa Adjective formed from nouns (idna-dOinakx, maasa-maaisakx), Derived from pronouns (saava_naaimak x naamao- hËa, Asalaa, tyaa) Quantity, Quality, Demonstrative (hËacaa) Distributive (ekxaca vaoLI ekxca baaoQa AsalaolaI-each), Adjective of number Comparison of Adjective: Comparative degree and Superlative degree, Interrogative Noun – naama Proper Noun, Common Noun, Abstract noun - example: (kxaOtaukx) Noun of things, Demonstrative, Interrogative, Noun of place, Noun of time, Honorific singular Noun - example: (AapaNa, -

Sentence Boundary Detection for Marathi Language

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Procedia Computer Science 78 ( 2016 ) 550 – 555 International Conference on Information Security & Privacy (ICISP2015), 11-12 December 2015, Nagpur, INDIA Sentence Boundary Detection For Marathi Language Nagmani Wanjaria*, Prof. G.M.Dhopavkarb, Nutan B. Zungrec a P.G.,Dept. of Computer Science and Engg., YCCE, Hingna Road, Nagpur-41110, India b Asst. Prof. Dept. of Cmputer Science and Engg.,YCCE, Hingna Road, Nagpur-41110,India Abstract Detecting the sentence boundary forms the basic step for many natural language applications. A lot of work has been done in this direction for English and other foreign languages. But not much work has been done for Indian languages. This paper proposes a rule based system for correctly identifying the boundary of the sentence written in Marathi. The task of identifying a sentence end in Marathi is made complex by the fact that Marathi language do not have indication of sentence start like the English has capital letters for indicating the start of new sentences. The system uses certain rules to correctly determine the end of sentence. © 2016 TheThe Authors. Authors. Published Published by by Elsevier Elsevier B.V. B.V. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (Peer-revihttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ew under responsibility of organizing committee). of the ICISP2015. Peer-review under responsibility of organizing committee of the ICISP2015 Keywords:natural language processing; sentence boundary detection; ambiguities 1. Introduction In most of the natural language application sentences forms the basic unit just above a word or a phrase [4]. -

Proceedings of the 16Th International Workshop on Treebanks and Linguistic Theories

TLT16 January 2018 Proceedings of the 16th International Workshop on Treebanks and Linguistic Theories January 23–24, 2018 Prague, Czech Republic ISBN: 978-80-88132-04-2 Edited by Jan Hajič. These proceedings with papers presented at the 16th International Workshop on Treebanks and Linguistic Theories are included in the ACL Anthology, supported by the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL) at http://aclweb.org/anthology; both individual papers as well as the full proceedings book are available. © 2017. Copyright of each paper stays with the respective authors (or their employers). Distributed under a CC-BY 4.0 licence. TLT16 takes place in Prague, Czech Republic on January 23–24, 2018. Preface The Sixteenth International Workshop on Treebanks and Linguistic Theories (TLT16) is being held at Charles University, Czech Republic, 23–24 January 2018, for the second time in Prague, which hosted TLT already in 2006. This year, TLT16 is co-located with the Workshop on Data Provenance and Annota- tion in Computational Linguistics 2018 (January 22, 2018, at the same place and venue) and immediately followed by the 2nd Workshop on Corpus-based Research in the Humanities, held in Vienna, Austria. This year, TLT16 received 32 submissions of which 15 have been selected to be presented as oral presentations, and additional seven have been asked to present as posters. We were happy that our in- vitation to give a plenary talk has been accepted by both Lilja Øvrelid of University of Oslo in Norway (with a talk “Downstream use of syntactic analysis: does representation matter?”) and Marie Candito, of University of Paris Diderot, France (“Annotating and parsing to semantic frames: feedback from the French FrameNet project”). -

Repor T Resumes

REPOR TRESUMES ED 020510. 46 AL 001 279 SURVEY OF MATERIALS IN THE NEGLECTED LANGUAGES,PART I (PRELIMINARY EDITION). CENTER FOR APPLIED LINGUISTICS, WASHINGTON, D.C. REPORT NUMBER BR...7...0929 PUB DATE JUN 68 CONTRACT 0EG...1-1...070929-4276 EDRS PRICEMF-S1.73 HC- $19.12 476P. DESCRIPTORS- *BIBLIOGRAPHIES, ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHIES, *UNCOMMONLY TAUGHT LANGUAGES, *INSTRUZTIONAL MATERIALS, TEXTBOOKS, READING MATERIALS, DICTIONARIES, AFRICAN LANGUAGES, AFRO ASIATIC LANGUAGES, AMERICAN INDIAN LANGUAGES, DRAVIDIAN LANGUAGES, FINNO UGRIC LANGUAGES, INDONESIAN LANGUAGES, MALAY() POLYNESIAN LANGUAGES, SEMITIC LANGUAGES, SINO TIBETAN LANGUAGES, SLAVIC LANGUAGES, URALIC AL7AIC LANGUAGES, INDO EUROPEAN LANGUAGES, THIS PRELIMINARY LIST OF STUDY AIDS FOR NEGLECTED LANGUAGES (THOSE NOT COMMONLY TAUGHT IN THE UNITED STATES) GIVES GREATEST EMPHASIS TO MATERIALS INTENDED FOR USE BYTHE ADULT LEARNER WHOSE NATIVE LANGUAGE IS ENGLISH. ITSENTRIES ARE ARRANGED ALPHABETICALLY BY LANGUAGE, ACHINESETO ZULU, AND INCLUDE TEXTS, GRAMMARS, READERS, DICTIONARIES,STUDIES OF WRITING SYSTEMS, AND LINGUISTIC DESCRIPTIONS.ACCOMPANYING TAPES, RECORDS, AND SLIDES ARE LISTED WHEREKNOWN. CREOLES ARE LISTED UNDER ENGLISH, FRENCH, PORTUGUESE, ORSPANISH ACCORDING TO THEIR LEXICAL BASE. BRIEF BUT COMPREHENSIVE ANNOTATIONS ARE SUPPLIED.FOR THE BASIC COURSES EXCEPTIN CASES WHERE THE BOOKS WERE UNAVAILABLE OR NOT AVAILABLE IN TIME FOR INCLUSION. THE FINAL EDITION, COMPLETELYANNOTATED ANDNDEXED, WILL BE PUBLISHED IN THE SPRING OF 1969. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION, WRITE THE FOREIGN LANGUAGES PROGRAM, CENTER FOR APPLIED LINGUISTICS, 1717 MASSACHUSETTSAVENUE, WAHINGTON, D.C. 20036. (DO) 72,07 o 9-27 OEC- . yg L5 SURVEY OF MATERIALS IN TOE NEGLECTED',ANGLIA hit l U.S. DEPARTMENT OFHEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCEDEXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATINGIT. -

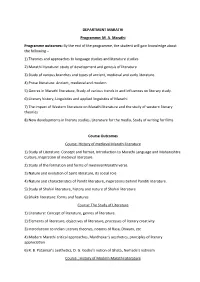

DEPARTMENT MARATHI Programme: M. A. Marathi Programme Outcomes: by the End of the Programme, the Student Will Gain Knowledge

DEPARTMENT MARATHI Programme: M. A. Marathi Programme outcomes: By the end of the programme, the student will gain knowledge about the following – 1) Theories and approaches to language studies and literature studies 2) Marathi literature: study of development and genesis of literature 3) Study of various branches and types of ancient, medieval and early literature. 4) Prose literature: Ancient, medieval and modern 5) Genres in Marathi literature, Study of various trends in and influences on literary study. 6) Literary history, Linguistics and applied linguistics of Marathi 7) The impact of Western literature on Marathi literature and the study of western literary theories 8) New developments in literary studies, Literature for the media, Study of writing for films Course Outcomes Course: History of medieval Marathi literature 1) Study of Literature: Concept and format, Introduction to Marathi Language and Maharashtra Culture, Inspiration of medieval literature. 2) Study of the formation and forms of medieval Marathi verse. 3) Nature and evolution of Saint literature, its social role 4) Nature and characteristics of Pandit literature, inspirations behind Panditi literature. 5) Study of Shahiri literature, history and nature of Shahiri literature 6) Bhakti literature: forms and features Course: The Study of Literature 1) Literature: Concept of literature, genres of literature. 2) Elements of literature, objectives of literature, processes of literary creativity 3) Introduction to Indian Literary theories, notions of Rasa, Dhwani, etc 4) Modern Marathi critical approaches, Mardhekar's aesthetics, principles of literary appreciation 6) R. B. Patankar's aesthetics, D. G. Godse's notion of Ghata, Nemade's nativism Course : History of Modern Marathi Literature 1) Cultural background of modern Marathi literature; impact of political, social, transcendental literature during British raj 2) Enlightenment and awakening in Maharashtra during early British rule, Emergence of Modern Literature.