The “Chrome Minnow” of North America Keeping and Spawning the Rainbow Shiner (Notropis Chrosomus)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carmine Shiner (Notropis Percobromus) in Canada

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Carmine Shiner Notropis percobromus in Canada THREATENED 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the carmine shiner Notropis percobromus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 29 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous reports COSEWIC 2001. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the carmine shiner Notropis percobromus and rosyface shiner Notropis rubellus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. v + 17 pp. Houston, J. 1994. COSEWIC status report on the rosyface shiner Notropis rubellus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-17 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge D.B. Stewart for writing the update status report on the carmine shiner Notropis percobromus in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Robert Campbell, Co-chair, COSEWIC Freshwater Fishes Species Specialist Subcommittee. In 1994 and again in 2001, COSEWIC assessed minnows belonging to the rosyface shiner species complex, including those in Manitoba, as rosyface shiner (Notropis rubellus). For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la tête carminée (Notropis percobromus) au Canada – Mise à jour. -

Notropis Girardi) and Peppered Chub (Macrhybopsis Tetranema)

Arkansas River Shiner and Peppered Chub SSA, October 2018 Species Status Assessment Report for the Arkansas River Shiner (Notropis girardi) and Peppered Chub (Macrhybopsis tetranema) Arkansas River shiner (bottom left) and peppered chub (top right - two fish) (Photo credit U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) Arkansas River Shiner and Peppered Chub SSA, October 2018 Version 1.0a October 2018 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 2 Albuquerque, NM This document was prepared by Angela Anders, Jennifer Smith-Castro, Peter Burck (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) – Southwest Regional Office) Robert Allen, Debra Bills, Omar Bocanegra, Sean Edwards, Valerie Morgan (USFWS –Arlington, Texas Field Office), Ken Collins, Patricia Echo-Hawk, Daniel Fenner, Jonathan Fisher, Laurence Levesque, Jonna Polk (USFWS – Oklahoma Field Office), Stephen Davenport (USFWS – New Mexico Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office), Mark Horner, Susan Millsap (USFWS – New Mexico Field Office), Jonathan JaKa (USFWS – Headquarters), Jason Luginbill, and Vernon Tabor (Kansas Field Office). Suggested reference: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2018. Species status assessment report for the Arkansas River shiner (Notropis girardi) and peppered chub (Macrhybopsis tetranema), version 1.0, with appendices. October 2018. Albuquerque, NM. 172 pp. Arkansas River Shiner and Peppered Chub SSA, October 2018 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ES.1 INTRODUCTION (CHAPTER 1) The Arkansas River shiner (Notropis girardi) and peppered chub (Macrhybopsis tetranema) are restricted primarily to the contiguous river segments of the South Canadian River basin spanning eastern New Mexico downstream to eastern Oklahoma (although the peppered chub is less widespread). Both species have experienced substantial declines in distribution and abundance due to habitat destruction and modification from stream dewatering or depletion from diversion of surface water and groundwater pumping, construction of impoundments, and water quality degradation. -

RFP No. 212F for Endangered Species Research Projects for the Prairie Chub

1 RFP No. 212f for Endangered Species Research Projects for the Prairie Chub Final Report Contributing authors: David S. Ruppel, V. Alex Sotola, Ozlem Ablak Gurbuz, Noland H. Martin, and Timothy H. Bonner Addresses: Department of Biology, Texas State University, San Marcos, Texas 78666 (DSR, VAS, NHM, THB) Kirkkonaklar Anatolian High School, Turkish Ministry of Education, Ankara, Turkey (OAG) Principal investigators: Timothy H. Bonner and Noland H. Martin Email: [email protected], [email protected] Date: July 31, 2017 Style: American Fisheries Society Funding sources: Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts, Turkish Ministry of Education- Visiting Scholar Program (OAG) Summary Four hundred mesohabitats were sampled from 36 sites and 20 reaches within the upper Red River drainage from September 2015 through September 2016. Fishes (N = 36,211) taken from the mesohabitats represented 14 families and 49 species with the most abundant species consisting of Red Shiner Cyprinella lutrensis, Red River Shiner Notropis bairdi, Plains Minnow Hybognathus placitus, and Western Mosquitofish Gambusia affinis. Red River Pupfish Cyprinodon rubrofluviatilis (a species of greatest conservation need, SGCN) and Plains Killifish Fundulus zebrinus were more abundant within prairie streams (e.g., swift and shallow runs with sand and silt substrates) with high specific conductance. Red River Shiner (SGCN), Prairie Chub Macrhybopsis australis (SGCN), and Plains Minnow were more abundant within prairie 2 streams with lower specific conductance. The remaining 44 species of fishes were more abundant in non-prairie stream habitats with shallow to deep waters, which were more common in eastern tributaries of the upper Red River drainage and Red River mainstem. Prairie Chubs comprised 1.3% of the overall fish community and were most abundant in Pease River and Wichita River. -

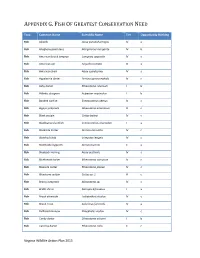

Fish of Greatest Conservation Need

APPENDIX G. FISH OF GREATEST CONSERVATION NEED Taxa Common Name Scientific Name Tier Opportunity Ranking Fish Alewife Alosa pseudoharengus IV a Fish Allegheny pearl dace Margariscus margarita IV b Fish American brook lamprey Lampetra appendix IV c Fish American eel Anguilla rostrata III a Fish American shad Alosa sapidissima IV a Fish Appalachia darter Percina gymnocephala IV c Fish Ashy darter Etheostoma cinereum I b Fish Atlantic sturgeon Acipenser oxyrinchus I b Fish Banded sunfish Enneacanthus obesus IV c Fish Bigeye jumprock Moxostoma ariommum III c Fish Black sculpin Cottus baileyi IV c Fish Blackbanded sunfish Enneacanthus chaetodon I a Fish Blackside darter Percina maculata IV c Fish Blotched chub Erimystax insignis IV c Fish Blotchside logperch Percina burtoni II a Fish Blueback Herring Alosa aestivalis IV a Fish Bluebreast darter Etheostoma camurum IV c Fish Blueside darter Etheostoma jessiae IV c Fish Bluestone sculpin Cottus sp. 1 III c Fish Brassy Jumprock Moxostoma sp. IV c Fish Bridle shiner Notropis bifrenatus I a Fish Brook silverside Labidesthes sicculus IV c Fish Brook Trout Salvelinus fontinalis IV a Fish Bullhead minnow Pimephales vigilax IV c Fish Candy darter Etheostoma osburni I b Fish Carolina darter Etheostoma collis II c Virginia Wildlife Action Plan 2015 APPENDIX G. FISH OF GREATEST CONSERVATION NEED Fish Carolina fantail darter Etheostoma brevispinum IV c Fish Channel darter Percina copelandi III c Fish Clinch dace Chrosomus sp. cf. saylori I a Fish Clinch sculpin Cottus sp. 4 III c Fish Dusky darter Percina sciera IV c Fish Duskytail darter Etheostoma percnurum I a Fish Emerald shiner Notropis atherinoides IV c Fish Fatlips minnow Phenacobius crassilabrum II c Fish Freshwater drum Aplodinotus grunniens III c Fish Golden Darter Etheostoma denoncourti II b Fish Greenfin darter Etheostoma chlorobranchium I b Fish Highback chub Hybopsis hypsinotus IV c Fish Highfin Shiner Notropis altipinnis IV c Fish Holston sculpin Cottus sp. -

Arkansas River Shiner Management Plan for the Canadian River 2 from U

FINAL - Submitted for Approval Arkansas River Shiner (Notropis girardi) Management Plan for the Canadian River From U. S. Highway 54 at Logan, New Mexico to Lake Meredith, Texas © Konrad Schmidt Canadian River Municipal Water Authority June 2005 Arkansas River Shiner Management Plan for the Canadian River 2 from U. S. Highway 54 at Logan, New Mexico to Lake Meredith Arkansas River Shiner (Notropis girardi) Management Plan for the Canadian River from U. S. Highway 54 at Logan, New Mexico to Lake Meredith, Texas This management plan is a cooperative effort between various local, state, and federal entities. Funding for this plan was provided by the Canadian River Municipal Water Authority. Suggested citation: Canadian River Municipal Water Authority – 2005 – Arkansas River Shiner (Notropis girardi) Management Plan for the Canadian River from U. S. Highway 54 at Logan, New Mexico to Lake Meredith, Texas Preparation of this Plan was accomplished by John C. Williams, acting as Special Advisor under contract to CRMWA. Technical review was provided by Rod Goodwin, Wildlife Biologist and Head of the Water Quality Division of CRMWA. Editorial review was performed by Jolinda Brumley. Cover photograph: Arkansas River Shiner by Ken Collins, USFWS Arkansas River Shiner Management Plan for the Canadian River 3 from U. S. Highway 54 at Logan, New Mexico to Lake Meredith Table of Contents Introduction and Background …………………………………………………………7 Species Biology ...................................................................................................................9 -

Geological Survey of Alabama Calibration of The

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF ALABAMA Berry H. (Nick) Tew, Jr. State Geologist WATER INVESTIGATIONS PROGRAM CALIBRATION OF THE INDEX OF BIOTIC INTEGRITY FOR THE SOUTHERN PLAINS ICHTHYOREGION IN ALABAMA OPEN-FILE REPORT 0908 by Patrick E. O'Neil and Thomas E. Shepard Prepared in cooperation with the Alabama Department of Environmental Management and the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Tuscaloosa, Alabama 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................ 1 Introduction.......................................................... 1 Acknowledgments .................................................... 6 Objectives........................................................... 7 Study area .......................................................... 7 Southern Plains ichthyoregion ...................................... 7 Methods ............................................................ 8 IBI sample collection ............................................. 8 Habitat measures............................................... 10 Habitat metrics ........................................... 12 The human disturbance gradient ................................... 15 IBI metrics and scoring criteria..................................... 19 Designation of guilds....................................... 20 Results and discussion................................................ 22 Sampling sites and collection results . 22 Selection and scoring of Southern Plains IBI metrics . 41 1. Number of native species ................................ -

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4—An Update April 2013 Prepared by: Pam L. Fuller, Amy J. Benson, and Matthew J. Cannister U.S. Geological Survey Southeast Ecological Science Center Gainesville, Florida Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia Cover Photos: Silver Carp, Hypophthalmichthys molitrix – Auburn University Giant Applesnail, Pomacea maculata – David Knott Straightedge Crayfish, Procambarus hayi – U.S. Forest Service i Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ v List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................ vi INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Overview of Region 4 Introductions Since 2000 ....................................................................................... 1 Format of Species Accounts ...................................................................................................................... 2 Explanation of Maps ................................................................................................................................ -

South Carolina Department of Natural Resources

FOREWORD Abundant fish and wildlife, unbroken coastal vistas, miles of scenic rivers, swamps and mountains open to exploration, and well-tended forests and fields…these resources enhance the quality of life that makes South Carolina a place people want to call home. We know our state’s natural resources are a primary reason that individuals and businesses choose to locate here. They are drawn to the high quality natural resources that South Carolinians love and appreciate. The quality of our state’s natural resources is no accident. It is the result of hard work and sound stewardship on the part of many citizens and agencies. The 20th century brought many changes to South Carolina; some of these changes had devastating results to the land. However, people rose to the challenge of restoring our resources. Over the past several decades, deer, wood duck and wild turkey populations have been restored, striped bass populations have recovered, the bald eagle has returned and more than half a million acres of wildlife habitat has been conserved. We in South Carolina are particularly proud of our accomplishments as we prepare to celebrate, in 2006, the 100th anniversary of game and fish law enforcement and management by the state of South Carolina. Since its inception, the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR) has undergone several reorganizations and name changes; however, more has changed in this state than the department’s name. According to the US Census Bureau, the South Carolina’s population has almost doubled since 1950 and the majority of our citizens now live in urban areas. -

COPEIA February 1

2000, No. 1COPEIA February 1 Copeia, 2000(1), pp. 1±10 Phylogenetic Relationships in the North American Cyprinid Genus Cyprinella (Actinopterygii: Cyprinidae) Based on Sequences of the Mitochondrial ND2 and ND4L Genes RICHARD E. BROUGHTON AND JOHN R. GOLD Shiners of the cyprinid genus Cyprinella are abundant and broadly distributed in eastern and central North America. Thirty species are currently placed in the genus: these include six species restricted to Mexico and three barbeled forms formerly placed in different cyprinid genera (primarily Hybopsis). We conducted a molecular phylogenetic analysis of all species of Cyprinella found in the United States, using complete nucleotide sequences of the mitochondrial, protein-coding genes ND2 and ND4L. Maximum-parsimony analysis recovered a single most-parsimonious tree for Cyprinella. Among historically recognized, nonbarbeled Cyprinella, the mitochondrial (mt) DNA tree indicated that basal lineages in Cyprinella are comprised largely of species with linear breeding tubercles and that are endemic to Atlantic and/or Gulf slope drainages, whereas derived lineages are comprised of species broadly distrib- uted in the Mississippi basin and the American Southwest. The Alabama Shiner, C. callistia, was basal in the mtDNA tree, although a monophyletic Cyprinella that in- cluded C. callistia was not supported in more than 50% of bootstrap replicates. There was strong bootstrap support (89%) for a clade that included all species of nonbarbeled Cyprinella (except C. callistia) and two barbeled species, C. labrosa and C. zanema. The third barbeled species, C. monacha, fell outside of Cyprinella sister to a species of Hybopsis. Within Cyprinella were a series of well-supported species groups, although in some cases bootstrap support for relationships among groups was below 50%. -

Basinwide Assessment Report Roanoke River Basin

BASINWIDE ASSESSMENT REPORT ROANOKE RIVER BASIN NORTH CAROLINA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES Division of Water Quality Environmental Sciences Section December 2010 This Page Left Intentionally Blank 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page LIST OF APPENDICES ...............................................................................................................................3 LIST OF TABLES.........................................................................................................................................3 LIST OF FIGURES.......................................................................................................................................4 INTRODUCTION TO PROGRAM METHODS..............................................................................................5 BASIN DESCRIPTION..................................................................................................................................6 ROA RIVER HUC 03010103—DAN RIVER HEADWATERS.......................................................................7 River and Stream Assessment .......................................................................................................7 ROA RIVER HUC 03010104—DAN RIVER……………………………………………………………………...9 River and Stream Assessment……………………………………………………………………….…..9 ROA RIVER HUC 03010102—JOHN H. KERR RESERVOIR………………………………………………..11 River and Stream Assessment………………………………………………………………………….11 ROA RIVER HUC 03010106—LAKE GASTON………………………………………………………………..13 River and Stream Assessment………………………………………………………………………….13 -

Summary Report of Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 5

Summary Report of Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 5 Summary Report of Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 5 Prepared by: Amy J. Benson, Colette C. Jacono, Pam L. Fuller, Elizabeth R. McKercher, U.S. Geological Survey 7920 NW 71st Street Gainesville, Florida 32653 and Myriah M. Richerson Johnson Controls World Services, Inc. 7315 North Atlantic Avenue Cape Canaveral, FL 32920 Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 4401 North Fairfax Drive Arlington, VA 22203 29 February 2004 Table of Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………... ...1 Aquatic Macrophytes ………………………………………………………………….. ... 2 Submersed Plants ………...………………………………………………........... 7 Emergent Plants ………………………………………………………….......... 13 Floating Plants ………………………………………………………………..... 24 Fishes ...…………….…………………………………………………………………..... 29 Invertebrates…………………………………………………………………………...... 56 Mollusks …………………………………………………………………………. 57 Bivalves …………….………………………………………………........ 57 Gastropods ……………………………………………………………... 63 Nudibranchs ………………………………………………………......... 68 Crustaceans …………………………………………………………………..... 69 Amphipods …………………………………………………………….... 69 Cladocerans …………………………………………………………..... 70 Copepods ……………………………………………………………….. 71 Crabs …………………………………………………………………...... 72 Crayfish ………………………………………………………………….. 73 Isopods ………………………………………………………………...... 75 Shrimp ………………………………………………………………….... 75 Amphibians and Reptiles …………………………………………………………….. 76 Amphibians ……………………………………………………………….......... 81 Toads and Frogs -

Natural Resource Condition Assessment Horseshoe Bend National Military Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Natural Resource Condition Assessment Horseshoe Bend National Military Park Natural Resource Report NPS/SECN/NRR—2015/981 ON THE COVER Photo of the Tallapoosa River, viewed from Horseshoe Bend National Military Park Photo Courtesy of Elle Allen Natural Resource Condition Assessment Horseshoe Bend National Military Park Natural Resource Report NPS/SECN/NRR—2015/981 JoAnn M. Burkholder, Elle H. Allen, Stacie Flood, and Carol A. Kinder Center for Applied Aquatic Ecology North Carolina State University 620 Hutton Street, Suite 104 Raleigh, NC 27606 June 2015 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. The series supports the advancement of science, informed decision-making, and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series also provides a forum for presenting more lengthy results that may not be accepted by publications with page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner.