Arkansas River Shiner Management Plan for the Canadian River 2 from U

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carmine Shiner (Notropis Percobromus) in Canada

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Carmine Shiner Notropis percobromus in Canada THREATENED 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the carmine shiner Notropis percobromus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 29 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous reports COSEWIC 2001. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the carmine shiner Notropis percobromus and rosyface shiner Notropis rubellus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. v + 17 pp. Houston, J. 1994. COSEWIC status report on the rosyface shiner Notropis rubellus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-17 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge D.B. Stewart for writing the update status report on the carmine shiner Notropis percobromus in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Robert Campbell, Co-chair, COSEWIC Freshwater Fishes Species Specialist Subcommittee. In 1994 and again in 2001, COSEWIC assessed minnows belonging to the rosyface shiner species complex, including those in Manitoba, as rosyface shiner (Notropis rubellus). For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la tête carminée (Notropis percobromus) au Canada – Mise à jour. -

A Many-Storied Place

A Many-storied Place Historic Resource Study Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas Theodore Catton Principal Investigator Midwest Region National Park Service Omaha, Nebraska 2017 A Many-Storied Place Historic Resource Study Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas Theodore Catton Principal Investigator 2017 Recommended: {){ Superintendent, Arkansas Post AihV'j Concurred: Associate Regional Director, Cultural Resources, Midwest Region Date Approved: Date Remove not the ancient landmark which thy fathers have set. Proverbs 22:28 Words spoken by Regional Director Elbert Cox Arkansas Post National Memorial dedication June 23, 1964 Table of Contents List of Figures vii Introduction 1 1 – Geography and the River 4 2 – The Site in Antiquity and Quapaw Ethnogenesis 38 3 – A French and Spanish Outpost in Colonial America 72 4 – Osotouy and the Changing Native World 115 5 – Arkansas Post from the Louisiana Purchase to the Trail of Tears 141 6 – The River Port from Arkansas Statehood to the Civil War 179 7 – The Village and Environs from Reconstruction to Recent Times 209 Conclusion 237 Appendices 241 1 – Cultural Resource Base Map: Eight exhibits from the Memorial Unit CLR (a) Pre-1673 / Pre-Contact Period Contributing Features (b) 1673-1803 / Colonial and Revolutionary Period Contributing Features (c) 1804-1855 / Settlement and Early Statehood Period Contributing Features (d) 1856-1865 / Civil War Period Contributing Features (e) 1866-1928 / Late 19th and Early 20th Century Period Contributing Features (f) 1929-1963 / Early 20th Century Period -

Notropis Girardi) and Peppered Chub (Macrhybopsis Tetranema)

Arkansas River Shiner and Peppered Chub SSA, October 2018 Species Status Assessment Report for the Arkansas River Shiner (Notropis girardi) and Peppered Chub (Macrhybopsis tetranema) Arkansas River shiner (bottom left) and peppered chub (top right - two fish) (Photo credit U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) Arkansas River Shiner and Peppered Chub SSA, October 2018 Version 1.0a October 2018 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 2 Albuquerque, NM This document was prepared by Angela Anders, Jennifer Smith-Castro, Peter Burck (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) – Southwest Regional Office) Robert Allen, Debra Bills, Omar Bocanegra, Sean Edwards, Valerie Morgan (USFWS –Arlington, Texas Field Office), Ken Collins, Patricia Echo-Hawk, Daniel Fenner, Jonathan Fisher, Laurence Levesque, Jonna Polk (USFWS – Oklahoma Field Office), Stephen Davenport (USFWS – New Mexico Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office), Mark Horner, Susan Millsap (USFWS – New Mexico Field Office), Jonathan JaKa (USFWS – Headquarters), Jason Luginbill, and Vernon Tabor (Kansas Field Office). Suggested reference: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2018. Species status assessment report for the Arkansas River shiner (Notropis girardi) and peppered chub (Macrhybopsis tetranema), version 1.0, with appendices. October 2018. Albuquerque, NM. 172 pp. Arkansas River Shiner and Peppered Chub SSA, October 2018 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ES.1 INTRODUCTION (CHAPTER 1) The Arkansas River shiner (Notropis girardi) and peppered chub (Macrhybopsis tetranema) are restricted primarily to the contiguous river segments of the South Canadian River basin spanning eastern New Mexico downstream to eastern Oklahoma (although the peppered chub is less widespread). Both species have experienced substantial declines in distribution and abundance due to habitat destruction and modification from stream dewatering or depletion from diversion of surface water and groundwater pumping, construction of impoundments, and water quality degradation. -

Lower Arkansas River – Derby to Ark City

LOWER ARKANSAS BASIN TOTAL MAXIMUM DAILY LOAD Waterbody/Assessment Unit (AU): Lower Arkansas River – Derby to Ark City Water Quality Impairment: Chloride 1. INTRODUCTION AND PROBLEM IDENTIFICATION Subbasin: Ark River (Derby), Ark River (Oxford), Ark River (Ark City), South Fork Ninnescah River, Ninnescah River, Slate Creek, Unmonitored Basin County: Cowley, Sumner, Sedgwick, Kingman, Pratt, Kiowa HUC 8: 11030013, 11030015, 11030016, 11060001 HUC 11 (HUC 14s): 11030013020(050) 11030013030(010, 030, 040, 050, 060, 070, 080, 090) 11030015010(010, 020, 030, 040, 050, 060, 070, 080, 090) 11030015030(010, 020, 030, 040, 050, 060) 11030016010(010, 020, 030, 040, 050) 11030016020(010, 020, 030) 11060001040(010) Ecoregion: Central Great Plains, Wellington-McPherson Lowland (27d) Flint Hills (28) Drainage Area: 1,653 square miles Main Stem Segments: 11030013 (AU Station 528): Slate Cr (17) (AU Station 281): Arkansas R (3-part) (AU Station 527): Arkansas R (2-part, 3-part, 18) (AU Station 218): Arkansas R (1, 2-part) 11030015 (AU Station 036): S.F. Ninnescah R (1,3,4,6) 11030016 (AU Station 280): Ninnescah R (1,3,8) 11060001 (AU Station 218): Arkansas R (14, 18) 1 Main Stem Segments with Tributaries by HUC 8 and Watershed/Station Number: Table 1 (a-f) a. HUC8 11030013 Watershed Slate Creek Station 528 Slate Cr (17) (partial) Winser Cr (32) Antelope Cr (25) Beaver Cr (29)* Hargis Cr (24)* Oak Cr (26)* Spring Cr (27)* * Not impaired b. HUC8 11030013 Watershed Arkansas River (Derby) Station 281 Arkansas R (3 - part) Spring Cr (37) c. HUC8 11030013 Watershed Arkansas River (Oxford) Station 527 Arkansas R (2 -part) Spring Cr (34) Lost Cr (23) Arkansas R (18) Arkansas R (3 - part) Bitter Cr (28) Dog Cr (531) d. -

The Arkansas River Flood of June 3-5, 1921

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ALBERT B. FALL, Secretary UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE 0ns SMITH, Director Water-Supply Paper 4$7 THE ARKANSAS RIVER FLOOD OF JUNE 3-5, 1921 BY ROBERT FOLLANS^EE AND EDWARD E. JON^S WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1922 i> CONTENTS. .Page. Introduction________________ ___ 5 Acknowledgments ___ __________ 6 Summary of flood losses-__________ _ 6 Progress of flood crest through Arkansas Valley _____________ 8 Topography of Arkansas basin_______________ _________ 9 Cause of flood______________1___________ ______ 11 Principal areas of intense rainfall____ ___ _ 15 Effect of reservoirs on the flood__________________________ 16 Flood flows_______________________________________ 19 Method of determination________________ ______ _ 19 The flood between Canon City and Pueblo_________________ 23 The flood at Pueblo________________________________ 23 General features_____________________________ 23 Arrival of tributary flood crests _______________ 25 Maximum discharge__________________________ 26 Total discharge_____________________________ 27 The flood below Pueblo_____________________________ 30 General features _________ _______________ 30 Tributary streams_____________________________ 31 Fountain Creek____________________________ 31 St. Charles River___________________________ 33 Chico Creek_______________________________ 34 Previous floods i____________________________________ 35 Flood of Indian legend_____________________________ 35 Floods of authentic record__________________________ 36 Maximum discharges -

RFP No. 212F for Endangered Species Research Projects for the Prairie Chub

1 RFP No. 212f for Endangered Species Research Projects for the Prairie Chub Final Report Contributing authors: David S. Ruppel, V. Alex Sotola, Ozlem Ablak Gurbuz, Noland H. Martin, and Timothy H. Bonner Addresses: Department of Biology, Texas State University, San Marcos, Texas 78666 (DSR, VAS, NHM, THB) Kirkkonaklar Anatolian High School, Turkish Ministry of Education, Ankara, Turkey (OAG) Principal investigators: Timothy H. Bonner and Noland H. Martin Email: [email protected], [email protected] Date: July 31, 2017 Style: American Fisheries Society Funding sources: Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts, Turkish Ministry of Education- Visiting Scholar Program (OAG) Summary Four hundred mesohabitats were sampled from 36 sites and 20 reaches within the upper Red River drainage from September 2015 through September 2016. Fishes (N = 36,211) taken from the mesohabitats represented 14 families and 49 species with the most abundant species consisting of Red Shiner Cyprinella lutrensis, Red River Shiner Notropis bairdi, Plains Minnow Hybognathus placitus, and Western Mosquitofish Gambusia affinis. Red River Pupfish Cyprinodon rubrofluviatilis (a species of greatest conservation need, SGCN) and Plains Killifish Fundulus zebrinus were more abundant within prairie streams (e.g., swift and shallow runs with sand and silt substrates) with high specific conductance. Red River Shiner (SGCN), Prairie Chub Macrhybopsis australis (SGCN), and Plains Minnow were more abundant within prairie 2 streams with lower specific conductance. The remaining 44 species of fishes were more abundant in non-prairie stream habitats with shallow to deep waters, which were more common in eastern tributaries of the upper Red River drainage and Red River mainstem. Prairie Chubs comprised 1.3% of the overall fish community and were most abundant in Pease River and Wichita River. -

Cultural Affiliation Statement for Buffalo National River

CULTURAL AFFILIATION STATEMENT BUFFALO NATIONAL RIVER, ARKANSAS Final Report Prepared by María Nieves Zedeño Nicholas Laluk Prepared for National Park Service Midwest Region Under Contract Agreement CA 1248-00-02 Task Agreement J6068050087 UAZ-176 Bureau of Applied Research In Anthropology The University of Arizona, Tucson AZ 85711 June 1, 2008 Table of Contents and Figures Summary of Findings...........................................................................................................2 Chapter One: Study Overview.............................................................................................5 Chapter Two: Cultural History of Buffalo National River ................................................15 Chapter Three: Protohistoric Ethnic Groups......................................................................41 Chapter Four: The Aboriginal Group ................................................................................64 Chapter Five: Emigrant Tribes...........................................................................................93 References Cited ..............................................................................................................109 Selected Annotations .......................................................................................................137 Figure 1. Buffalo National River, Arkansas ........................................................................6 Figure 2. Sixteenth Century Polities and Ethnic Groups (after Sabo 2001) ......................47 -

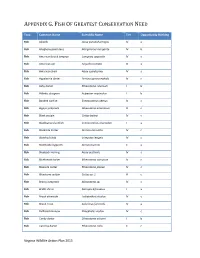

Fish of Greatest Conservation Need

APPENDIX G. FISH OF GREATEST CONSERVATION NEED Taxa Common Name Scientific Name Tier Opportunity Ranking Fish Alewife Alosa pseudoharengus IV a Fish Allegheny pearl dace Margariscus margarita IV b Fish American brook lamprey Lampetra appendix IV c Fish American eel Anguilla rostrata III a Fish American shad Alosa sapidissima IV a Fish Appalachia darter Percina gymnocephala IV c Fish Ashy darter Etheostoma cinereum I b Fish Atlantic sturgeon Acipenser oxyrinchus I b Fish Banded sunfish Enneacanthus obesus IV c Fish Bigeye jumprock Moxostoma ariommum III c Fish Black sculpin Cottus baileyi IV c Fish Blackbanded sunfish Enneacanthus chaetodon I a Fish Blackside darter Percina maculata IV c Fish Blotched chub Erimystax insignis IV c Fish Blotchside logperch Percina burtoni II a Fish Blueback Herring Alosa aestivalis IV a Fish Bluebreast darter Etheostoma camurum IV c Fish Blueside darter Etheostoma jessiae IV c Fish Bluestone sculpin Cottus sp. 1 III c Fish Brassy Jumprock Moxostoma sp. IV c Fish Bridle shiner Notropis bifrenatus I a Fish Brook silverside Labidesthes sicculus IV c Fish Brook Trout Salvelinus fontinalis IV a Fish Bullhead minnow Pimephales vigilax IV c Fish Candy darter Etheostoma osburni I b Fish Carolina darter Etheostoma collis II c Virginia Wildlife Action Plan 2015 APPENDIX G. FISH OF GREATEST CONSERVATION NEED Fish Carolina fantail darter Etheostoma brevispinum IV c Fish Channel darter Percina copelandi III c Fish Clinch dace Chrosomus sp. cf. saylori I a Fish Clinch sculpin Cottus sp. 4 III c Fish Dusky darter Percina sciera IV c Fish Duskytail darter Etheostoma percnurum I a Fish Emerald shiner Notropis atherinoides IV c Fish Fatlips minnow Phenacobius crassilabrum II c Fish Freshwater drum Aplodinotus grunniens III c Fish Golden Darter Etheostoma denoncourti II b Fish Greenfin darter Etheostoma chlorobranchium I b Fish Highback chub Hybopsis hypsinotus IV c Fish Highfin Shiner Notropis altipinnis IV c Fish Holston sculpin Cottus sp. -

Endangered Species

FEATURE: ENDANGERED SPECIES Conservation Status of Imperiled North American Freshwater and Diadromous Fishes ABSTRACT: This is the third compilation of imperiled (i.e., endangered, threatened, vulnerable) plus extinct freshwater and diadromous fishes of North America prepared by the American Fisheries Society’s Endangered Species Committee. Since the last revision in 1989, imperilment of inland fishes has increased substantially. This list includes 700 extant taxa representing 133 genera and 36 families, a 92% increase over the 364 listed in 1989. The increase reflects the addition of distinct populations, previously non-imperiled fishes, and recently described or discovered taxa. Approximately 39% of described fish species of the continent are imperiled. There are 230 vulnerable, 190 threatened, and 280 endangered extant taxa, and 61 taxa presumed extinct or extirpated from nature. Of those that were imperiled in 1989, most (89%) are the same or worse in conservation status; only 6% have improved in status, and 5% were delisted for various reasons. Habitat degradation and nonindigenous species are the main threats to at-risk fishes, many of which are restricted to small ranges. Documenting the diversity and status of rare fishes is a critical step in identifying and implementing appropriate actions necessary for their protection and management. Howard L. Jelks, Frank McCormick, Stephen J. Walsh, Joseph S. Nelson, Noel M. Burkhead, Steven P. Platania, Salvador Contreras-Balderas, Brady A. Porter, Edmundo Díaz-Pardo, Claude B. Renaud, Dean A. Hendrickson, Juan Jacobo Schmitter-Soto, John Lyons, Eric B. Taylor, and Nicholas E. Mandrak, Melvin L. Warren, Jr. Jelks, Walsh, and Burkhead are research McCormick is a biologist with the biologists with the U.S. -

Arkansas V. Oklahoma: Restoring the Notion of Partnership Under the Clean Water Act Katheryn Kim Frierson [email protected]

University of Chicago Legal Forum Volume 1997 | Issue 1 Article 16 Arkansas v. Oklahoma: Restoring the Notion of Partnership under the Clean Water Act Katheryn Kim Frierson [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf Recommended Citation Frierson, Katheryn Kim () "Arkansas v. Oklahoma: Restoring the Notion of Partnership under the Clean Water Act," University of Chicago Legal Forum: Vol. 1997: Iss. 1, Article 16. Available at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1997/iss1/16 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Chicago Legal Forum by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Arkansas v Oklahoma: Restoring the Notion of Partnership Under the Clean Water Act Katheryn Kim Friersont The long history of interstate water pollution disputes traces the steady rise of federal regulatory power in the area of environ- mental policy, culminating in the passage of the Clean Water Act Amendments of 1972.1 Arkansas v Oklahoma2 is the third and latest Supreme Court decision involving interstate water pol- lution since the passage of the 1972 amendments. By all ac- counts, Arkansas is wholly consistent with the Court's prior decisions. In Milwaukee v Illinois3 and InternationalPaper Co. v Ouellette,4 the Court held that the Clean Water Act ("CWA") preempted all traditional common law and state law remedies. Consequently, states lost much of their traditional authority to direct water pollution policies. Despite the claim that the CWA intended "a regulatory 'partnership' between the Federal Govern- ment and the source State", Milwaukee and InternationalPaper placed states in a subordinate position to the federal govern- t B.A. -

Aquatic Fish Report

Aquatic Fish Report Acipenser fulvescens Lake St urgeon Class: Actinopterygii Order: Acipenseriformes Family: Acipenseridae Priority Score: 27 out of 100 Population Trend: Unknown Gobal Rank: G3G4 — Vulnerable (uncertain rank) State Rank: S2 — Imperiled in Arkansas Distribution Occurrence Records Ecoregions where the species occurs: Ozark Highlands Boston Mountains Ouachita Mountains Arkansas Valley South Central Plains Mississippi Alluvial Plain Mississippi Valley Loess Plains Acipenser fulvescens Lake Sturgeon 362 Aquatic Fish Report Ecobasins Mississippi River Alluvial Plain - Arkansas River Mississippi River Alluvial Plain - St. Francis River Mississippi River Alluvial Plain - White River Mississippi River Alluvial Plain (Lake Chicot) - Mississippi River Habitats Weight Natural Littoral: - Large Suitable Natural Pool: - Medium - Large Optimal Natural Shoal: - Medium - Large Obligate Problems Faced Threat: Biological alteration Source: Commercial harvest Threat: Biological alteration Source: Exotic species Threat: Biological alteration Source: Incidental take Threat: Habitat destruction Source: Channel alteration Threat: Hydrological alteration Source: Dam Data Gaps/Research Needs Continue to track incidental catches. Conservation Actions Importance Category Restore fish passage in dammed rivers. High Habitat Restoration/Improvement Restrict commercial harvest (Mississippi River High Population Management closed to harvest). Monitoring Strategies Monitor population distribution and abundance in large river faunal surveys in cooperation -

State Abbreviations

State Abbreviations Postal Abbreviations for States/Territories On July 1, 1963, the Post Office Department introduced the five-digit ZIP Code. At the time, 10/1963– 1831 1874 1943 6/1963 present most addressing equipment could accommodate only 23 characters (including spaces) in the Alabama Al. Ala. Ala. ALA AL Alaska -- Alaska Alaska ALSK AK bottom line of the address. To make room for Arizona -- Ariz. Ariz. ARIZ AZ the ZIP Code, state names needed to be Arkansas Ar. T. Ark. Ark. ARK AR abbreviated. The Department provided an initial California -- Cal. Calif. CALIF CA list of abbreviations in June 1963, but many had Colorado -- Colo. Colo. COL CO three or four letters, which was still too long. In Connecticut Ct. Conn. Conn. CONN CT Delaware De. Del. Del. DEL DE October 1963, the Department settled on the District of D. C. D. C. D. C. DC DC current two-letter abbreviations. Since that time, Columbia only one change has been made: in 1969, at the Florida Fl. T. Fla. Fla. FLA FL request of the Canadian postal administration, Georgia Ga. Ga. Ga. GA GA Hawaii -- -- Hawaii HAW HI the abbreviation for Nebraska, originally NB, Idaho -- Idaho Idaho IDA ID was changed to NE, to avoid confusion with Illinois Il. Ill. Ill. ILL IL New Brunswick in Canada. Indiana Ia. Ind. Ind. IND IN Iowa -- Iowa Iowa IOWA IA Kansas -- Kans. Kans. KANS KS A list of state abbreviations since 1831 is Kentucky Ky. Ky. Ky. KY KY provided at right. A more complete list of current Louisiana La. La.