Tim Berners-Lee, Winner of the 2016 Turing Award for Having Invented… the Web Fabien Gandon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The World Wide Web: Not So World Wide After All?, 16 Pub

Public Interest Law Reporter Volume 16 Article 8 Issue 1 Fall 2010 2010 The orW ld Wide Web: Not So World Wide After All? Allison Lockhart Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/pilr Part of the Internet Law Commons Recommended Citation Allison Lockhart, The World Wide Web: Not So World Wide After All?, 16 Pub. Interest L. Rptr. 47 (2010). Available at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/pilr/vol16/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Public Interest Law Reporter by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lockhart: The World Wide Web: Not So World Wide After All? No. 1 • Fall 2010 THE WORLD WIDE WEB: NOT SO WORLD WIDE AFTER ALL? by ALLISON LOCKHART It’s hard to imagine not having twenty-four hour access to videos of dancing Icats or Ashton Kutcher’s hourly musings, but this is the reality in many countries. In an attempt to control what some governments perceive as a law- less medium, China, Saudi Arabia, Cuba, and a growing number of other countries have begun censoring content on the Internet.1 The most common form of censorship involves blocking access to certain web- sites, but the governments in these countries also employ companies to prevent search results from listing what they deem inappropriate.2 Other governments have successfully censored material on the Internet by simply invoking in the minds of its citizens a fear of punishment or ridicule that encourages self- censoring.3 47 Published by LAW eCommons, 2010 1 Public Interest Law Reporter, Vol. -

The Origins of the Underline As Visual Representation of the Hyperlink on the Web: a Case Study in Skeuomorphism

The Origins of the Underline as Visual Representation of the Hyperlink on the Web: A Case Study in Skeuomorphism The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Romano, John J. 2016. The Origins of the Underline as Visual Representation of the Hyperlink on the Web: A Case Study in Skeuomorphism. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33797379 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Origins of the Underline as Visual Representation of the Hyperlink on the Web: A Case Study in Skeuomorphism John J Romano A Thesis in the Field of Visual Arts for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University November 2016 Abstract This thesis investigates the process by which the underline came to be used as the default signifier of hyperlinks on the World Wide Web. Created in 1990 by Tim Berners- Lee, the web quickly became the most used hypertext system in the world, and most browsers default to indicating hyperlinks with an underline. To answer the question of why the underline was chosen over competing demarcation techniques, the thesis applies the methods of history of technology and sociology of technology. Before the invention of the web, the underline–also known as the vinculum–was used in many contexts in writing systems; collecting entities together to form a whole and ascribing additional meaning to the content. -

Role of Librarian in Internet and World Wide Web Environment K

Informing Science Information Sciences Volume 4 No 1, 2001 Role of Librarian in Internet and World Wide Web Environment K. Nageswara Rao and KH Babu Defence Research & Development Laboratory Kanchanbagh Post, India [email protected] and [email protected] Abstract The transition of traditional library collections to digital or virtual collections presented the librarian with new opportunities. The Internet, Web en- vironment and associated sophisticated tools have given the librarian a new dynamic role to play and serve the new information based society in bet- ter ways than hitherto. Because of the powerful features of Web i.e. distributed, heterogeneous, collaborative, multimedia, multi-protocol, hyperme- dia-oriented architecture, World Wide Web has revolutionized the way people access information, and has opened up new possibilities in areas such as digital libraries, virtual libraries, scientific information retrieval and dissemination. Not only the world is becoming interconnected, but also the use of Internet and Web has changed the fundamental roles, paradigms, and organizational culture of libraries and librarians as well. The article describes the limitless scope of Internet and Web, the existence of the librarian in the changing environment, parallelism between information sci- ence and information technology, librarians and intelligent agents, working of intelligent agents, strengths, weaknesses, threats and opportunities in- volved in the relationship between librarians and the Web. The role of librarian in Internet and Web environment especially as intermediary, facilita- tor, end-user trainer, Web site builder, researcher, interface designer, knowledge manager and sifter of information resources is also described. Keywords: Role of Librarian, Internet, World Wide Web, Data Mining, Meta Data, Latent Semantic Indexing, Intelligent Agents, Search Intermediary, Facilitator, End-User Trainer, Web Site Builder, Researcher, Interface Designer, Knowledge Man- ager, Sifter. -

TRABAJO DE DIPLOMA Título: Diseño De La Página Web De Antenas

FACULTAD DE INGENIERÍA ELÉCTRICA Departamento de Telecomunicaciones y Electrónica TRABAJO DE DIPLOMA Título: Diseño de la Página Web de Antenas Autor: Alaín Hidalgo Burgos Tutor: Dr. Roberto Jiménez Hernández Santa Clara 2006 “Año de la Revolución Energética en Cuba” Universidad Central “Marta Abreu” de Las Villas FACULTAD DE INGENIERÍA ELÉCTRICA Departamento de Telecomunicaciones y Electrónica TTRRAABBAAJJOO DDEE DDIIPPLLOOMMAA Diseño de la Página Web de Antenas Autor: Alaín Hidalgo Burgos e-mail: [email protected] Tutor: Dr. Roberto Jiménez Hernández Prof. Dpto. de Telecomunicaciones y electrónica Facultad de Ing. Eléctrica. UCLV. e-mail: [email protected] Santa Clara Curso 2005-2006 “Año de la Revolución Energética en Cuba” Hago constar que el presente trabajo de diploma fue realizado en la Universidad Central “Marta Abreu” de Las Villas como parte de la culminación de estudios de la especialidad de Ingeniería en Telecomunicaciones y Electrónica, autorizando a que el mismo sea utilizado por la Institución, para los fines que estime conveniente, tanto de forma parcial como total y que además no podrá ser presentado en eventos, ni publicados sin autorización de la Universidad. Firma del Autor Los abajo firmantes certificamos que el presente trabajo ha sido realizado según acuerdo de la dirección de nuestro centro y el mismo cumple con los requisitos que debe tener un trabajo de esta envergadura referido a la temática señalada. Firma del Tutor Firma del Jefe de Departamento donde se defiende el trabajo Firma del Responsable de Información Científico-Técnica PENSAMIENTO “El néctar de la victoria se bebe en la copa del sacrificio” DEDICATORIA Dedico este trabajo a mis padres, a mí hermana y a mi novia por ser las personas más hermosas que existen y a las cuales les debo todo. -

Cascading Style Sheet Styling Issues for Punjabi Language

Cascading Style Sheet Styling Issues for Punjabi Language Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of degree of Master of Engineering in Computer Science and Engineering Submitted By Swati Mittal (Roll No. 800932024) Under the supervision of: Mr. Parteek Bhatia Assistant Professor (CSED) COMPUTER SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT THAPAR UNIVERSITY PATIALA – 147004 June 2011 i ii Abstract Most of the websites today are multilingual. The information provided on the Internet is in local language. The fonts used for local languages are not compatible with the browsers. The websites make use of Cascading Style Sheets for styling. The effect of using CSS styles on local languages is not as good as it is for English language. There are many CSS styling issues in display of local languages. W3C India has identified many CSS styling issues for Indic Scripts. In the work presented, CSS styling issues like, first-letter styling, underlining, over lining, line- through of characters, hyperlink display while mouse over, horizontal spacing, etc., have been discussed for Punjabi language. These issues have been analyzed on six different browsers, namely, Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, Netscape Navigator, Safari, Internet Explorer and Opera. A comparative study of all these browsers has been carried out based on the CSS styling issues. A number of Punjabi websites have been analyzed to find the problems in display. The websites use Unicode and non-Unicode Gurmukhi fonts for Punjabi content. There are problems in display of non-Unicode fonts. A web application has been created that allows an end-user to apply different CSS styles on the Punjabi text. -

(Hardening) De Navegadores Web Más Utilizados

UNIVERSIDAD DON BOSCO VICERRECTORÍA DE ESTUDIOS DE POSTGRADO TRABAJO DE GRADUACIÓN Endurecimiento (Hardening) de navegadores web más utilizados. Caso práctico: Implementación de navegadores endurecidos (Microsoft Internet Explorer, Mozilla Firefox y Google Chrome) en un paquete integrado para Microsoft Windows. PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE: MAESTRO EN SEGURIDAD Y GESTION DEL RIESGO INFORMATICO ASESOR: Mg. JOSÉ MAURICIO FLORES AVILÉS PRESENTADO POR: ERICK ALFREDO FLORES AGUILAR Antiguo Cuscatlán, La Libertad, El Salvador, Centroamérica Febrero de 2015 AGRADECIMIENTOS A Dios Todopoderoso, por regalarme vida, salud y determinación para alcanzar un objetivo más en mi vida. A mi amada esposa, que me acompaño durante toda mi carrera, apoyó y comprendió mi dedicación de tiempo y esfuerzo a este proyecto y nunca dudó que lo concluiría con bien. A mis padres y hermana, que siempre han sido mis pilares y me enseñaron que lo mejor que te pueden regalar en la vida es una buena educación. A mis compañeros de trabajo, que mediante su esfuerzo extraordinario me han permitido contar con el tiempo necesario para dedicar mucho más tiempo a la consecución de esta meta. A mis amigos de los que siempre he tenido una palabra de aliento cuando la he necesitado. A mi supervisor y compañeros de la Escuela de Computación de la Universidad de Queens por facilitarme espacio, recursos, tiempo e información valiosa para la elaboración de este trabajo. A mi asesor de tesis, al director del programa de maestría y mis compañeros de la carrera, que durante estos dos años me han ayudado a lograr esta meta tan importante. Erick Alfredo Flores Aguilar INDICE I. -

Ali Aydar Anita Borg Alfred Aho Bjarne Stroustrup Bill Gates

Ali Aydar Ali Aydar is a computer scientist and Internet entrepreneur. He is the chief executive officer at Sporcle. He is best known as an early employee and key technical contributor at the original Napster. Aydar bought Fanning his first book on programming in C++, the language he would use two years later to build the Napster file-sharing software. Anita Borg Anita Borg (January 17, 1949 – April 6, 2003) was an American computer scientist. She founded the Institute for Women and Technology (now the Anita Borg Institute for Women and Technology). While at Digital Equipment, she developed and patented a method for generating complete address traces for analyzing and designing high-speed memory systems. Alfred Aho Alfred Aho (born August 9, 1941) is a Canadian computer scientist best known for his work on programming languages, compilers, and related algorithms, and his textbooks on the art and science of computer programming. Aho received a B.A.Sc. in Engineering Physics from the University of Toronto. Bjarne Stroustrup Bjarne Stroustrup (born 30 December 1950) is a Danish computer scientist, most notable for the creation and development of the widely used C++ programming language. He is a Distinguished Research Professor and holds the College of Engineering Chair in Computer Science. Bill Gates 2 of 10 Bill Gates (born October 28, 1955) is an American business magnate, philanthropist, investor, computer programmer, and inventor. Gates is the former chief executive and chairman of Microsoft, the world’s largest personal-computer software company, which he co-founded with Paul Allen. Bruce Arden Bruce Arden (born in 1927 in Minneapolis, Minnesota) is an American computer scientist. -

Unreasonable Expectations: an Examination of the Semantic Web

Unreasonable Expectations: An Examination of the Semantic Web in the Light of the Original Vision for the Project Dónal Deery A research paper submitted to the University of Dublin, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Interactive Digital Media 2014 Declaration I declare that the work described in this research paper is, except where otherwise stated, entirely my own work and has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university. Signed: ___________________ Dónal Deery 28th February 2014 Permission to lend and/or copy I agree that Trinity College Library may lend or copy this research Paper upon request. Signed: ___________________ Dónal Deery 28th February 2014 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Rachel O’Dwyer for her advice, patience, and grammatical assistance during the preparation of this paper. I would also like to thank my parents for their continuing support and positivity. Summary This paper is concerned with the relationship between the Semantic Web as it was originally envisioned and the present status of the endeavour. The Semantic Web is an enhanced version of the existing World Wide Web in which data that can be processed by computers is added to web pages in order to make it easier for users to locate and exchange information. It was proposed by Sir Tim Berners-Lee, the invention of the original Web. The paper begins with a consideration of the original vision for the Semantic Web outlined by Berners-Lee and others around the turn of the millennium. -

![Chronologie [Modifier] Les Premières Années De Cet Historique Sont Largement Basées Sur a Little History of the World Wide Web (Une Petite Histoire Du World Wide Web)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7437/chronologie-modifier-les-premi%C3%A8res-ann%C3%A9es-de-cet-historique-sont-largement-bas%C3%A9es-sur-a-little-history-of-the-world-wide-web-une-petite-histoire-du-world-wide-web-477437.webp)

Chronologie [Modifier] Les Premières Années De Cet Historique Sont Largement Basées Sur a Little History of the World Wide Web (Une Petite Histoire Du World Wide Web)

Chronologie [modifier] Les premières années de cet historique sont largement basées sur A Little History of the World Wide Web (Une petite histoire du World Wide Web). 1989 Tim Berners-Lee, engagé au CERN à Genève en 1984 pour travailler sur l’acquisition et le traitement des données10, propose de développer un système hypertexte organisé en web, afin d’améliorer la diffusion des informations internes : Information Management: A Proposal7. 1990 Le premier serveur web, unNeXT Cube Robert Cailliau rejoint le projet et collabore à la révision de la proposition : WorldWideWeb: Proposal for a HyperText Project2. Étendue : Le premier serveur web est nxoc01.cern.ch ; la première page web est http://nxoc01.cern.ch/hypertext/WWW/TheProject.html ; la plus ancienne page conservée date du 13 novembre. Logiciels : Le premier navigateur, appelé WorldWideWeb (plus tard rebaptisé Nexus) est développé en Objective C sur NeXT [1]. En plus d’être un navigateur, WorldWideWeb est un éditeur web. Le navigateur mode texte line- mode est développé en langage C pour être portable sur les nombreux modèles d’ordinateurs et simples terminaux de l’époque. Technologies : Les trois technologies à la base du Web, URL, HTML et HTTP, sont à l’œuvre. Sur NeXT, des feuilles de style simples sont également utilisées, ce qui ne sera plus le cas jusqu’à l’apparition des Cascading Style Sheets. 1991 Le 6 août, Tim Berners-Lee rend le projet WorldWideWeb public dans un message sur Usenet [2]. Étendue : premier serveur web hors d’Europe au SLAC ; passerelle avec WAIS [3]. Logiciels : fichiers développés au CERN disponibles par FTP. -

The Founding, Fantastic Growth, and Fast Decline of Norsk Data AS Tor Steine

The Founding, Fantastic Growth, and Fast Decline of Norsk Data AS Tor Steine To cite this version: Tor Steine. The Founding, Fantastic Growth, and Fast Decline of Norsk Data AS. 3rd History of Nordic Computing (HiNC), Oct 2010, Stockholm, Sweden. pp.249-257, 10.1007/978-3-642-23315- 9_28. hal-01564615 HAL Id: hal-01564615 https://hal.inria.fr/hal-01564615 Submitted on 19 Jul 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License The Founding, Fantastic Growth, and Fast Decline of Norsk Data AS Tor Olav Steine Formerly of Norsk Data AS [email protected] Abstract. Norsk Data was a remarkable company that in just twenty years went from a glimmer in the eyes of some computer enthusiasts to become number two in share value at the Oslo Stock Exchange. Within a few years thereafter, it collapsed, for no obvious reason. How was this tremendous success possible and why did the company collapse? Keywords: Collapse, computer, F16, industry, minicomputer, Norsk Data, Nord, simulator, success, Supermini 1 The Beginning 1.1 FFI A combination of circumstances led to the founding of Norsk Data1 in June 1967. -

Security Analysis of Browser Extension Concepts

Saarland University Faculty of Natural Sciences and Technology I Department of Computer Science Bachelor's thesis Security Analysis of Browser Extension Concepts A comparison of Internet Explorer 9, Safari 5, Firefox 8, and Chrome 14 submitted by Karsten Knuth submitted January 14, 2012 Supervisor Prof. Dr. Michael Backes Advisors Raphael Reischuk Sebastian Gerling Reviewers Prof. Dr. Michael Backes Dr. Matteo Maffei Statement in Lieu of an Oath I hereby confirm that I have written this thesis on my own and that I have not used any other media or materials than the ones referred to in this thesis. Saarbr¨ucken, January 14, 2012 Karsten Knuth Declaration of Consent I agree to make both versions of my thesis (with a passing grade) accessible to the public by having them added to the library of the Computer Science Department. Saarbr¨ucken, January 14, 2012 Karsten Knuth Acknowledgments First of all, I thank Professor Dr. Michael Backes for giving me the chance to write my bachelor's thesis at the Information Security & Cryptography chair. During the making of this thesis I have gotten a deeper look in a topic which I hope to be given the chance to follow up in my upcoming academic career. Furthermore, I thank my advisors Raphael Reischuk, Sebastian Gerling, and Philipp von Styp-Rekowsky for supporting me with words and deeds during the making of this thesis. In particular, I thank the first two for bearing with me since the release of my topic. My thanks also go to Lara Schneider and Michael Zeidler for offering me helpful advice. -

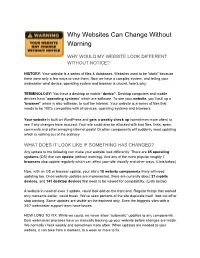

Why Websites Can Change Without Warning

Why Websites Can Change Without Warning WHY WOULD MY WEBSITE LOOK DIFFERENT WITHOUT NOTICE? HISTORY: Your website is a series of files & databases. Websites used to be “static” because there were only a few ways to view them. Now we have a complex system, and telling your webmaster what device, operating system and browser is crucial, here’s why: TERMINOLOGY: You have a desktop or mobile “device”. Desktop computers and mobile devices have “operating systems” which are software. To see your website, you’ll pull up a “browser” which is also software, to surf the Internet. Your website is a series of files that needs to be 100% compatible with all devices, operating systems and browsers. Your website is built on WordPress and gets a weekly check up (sometimes more often) to see if any changes have occured. Your site could also be attacked with bad files, links, spam, comments and other annoying internet pests! Or other components will suddenly need updating which is nothing out of the ordinary. WHAT DOES IT LOOK LIKE IF SOMETHING HAS CHANGED? Any update to the following can make your website look differently: There are 85 operating systems (OS) that can update (without warning). And any of the most popular roughly 7 browsers also update regularly which can affect your site visually and other ways. (Lists below) Now, with an OS or browser update, your site’s 18 website components likely will need updating too. Once website updates are implemented, there are currently about 21 mobile devices, and 141 desktop devices that need to be viewed for compatibility.