Myanmar 2014-2016 / Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remaking Rakhine State

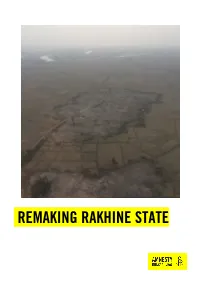

REMAKING RAKHINE STATE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Aerial photograph showing the clearance of a burnt village in northern Rakhine State (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Private https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 16/8018/2018 Original language: English amnesty.org INTRODUCTION Six months after the start of a brutal military campaign which forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya women, men and children from their homes and left hundreds of Rohingya villages burned the ground, Myanmar’s authorities are remaking northern Rakhine State in their absence.1 Since October 2017, but in particular since the start of 2018, Myanmar’s authorities have embarked on a major operation to clear burned villages and to build new homes, security force bases and infrastructure in the region. -

July 2020 (23:45 Yangon Time)

Allocation Strategy Paper 2020: FIRST STANDARD ALLOCATION DEADLINE: Monday, 20 July 2020 (23:45 Yangon time) I. ALLOCATION OVERVIEW I.1. Introduction This document lays the strategy to allocating funds from the Myanmar Humanitarian Fund (MHF) First Standard Allocation to scale up the response to the protracted humanitarian crises in Myanmar, in line with the 2020 Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP). The allocation responds also to the critical underfunded situation of humanitarian requirements by mid-June 2020. As of 20 June, only 23 per cent of the 2020 HRP requirements, including the revised COVID-19 Addendum, have been met up to now (29 per cent in the case of the mentioned addendum), which is very low in comparison with donor contributions against the HRP in previous years for the same period (50 per cent in 2019 and 40 per cent in 2018). This standard allocation will make available about US$7 million to support coordinated humanitarian assistance and protection, covering displaced people and other vulnerable crisis-affected people in Chin, Rakhine, Kachin and Shan states. The allocation will not include stand-alone interventions related to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), which has been already supported through a Reserve Allocation launched in April 2020, resulting in ten funded projects amounting a total of $3.8 million that are already being implemented. Nevertheless, COVID-19 related actions may be mainstreamed throughout the response to the humanitarian needs. In addition, activities in Kayin State will not be included in this allocation, due to the ongoing projects and level of funding as per HRP requirements. -

Acknowledgments

FACTORS AFFECTING COMMERCIALIZATION OF THE RURAL LIVESTOCK SECTOR Acknowledgments Thisresearch study was led by U Kyaw Khine & Associates with the assistance of the field survey team of the FSWG members organizations. The research team would like to express sincere thanks to Dr Ohnmar Khaing (FSWG Coordinator), Dr. Min Ko Ko Maung, (Deputy Coordinator), and Mr. Thijs Wissink (Programme Advisor) for their kind and effective support for the research. The team is especially grateful to Daw Yi Yi Cho (M&E Officer) for providing logistical and technical support along with study design, data collection, analysis, and report writing. Finally, this research would not have been possible without the valuable participation and knowledge imparted by all the respondents from the villages of Pauktaw and Taungup Townships and focus group discussion (FGD) participants. The research team would like to acknowledge the experts and professors from respective institutions concerned with livestock who willingly agreed to take part in the FGDs. We are greatly indebted to them. 1 FACTORS AFFECTING COMMERCIALIZATION OF THE RURAL LIVESTOCK SECTOR Ensure adequate financial and human resources to village volunteers for veterinary extension services to cover all rural areas Upgrade local pig breeds with improved variety for better genetic performance in rural livestock production Attract private sector investment to finance all livestock support infrastructure, such as cold chain, cold storage, animal feed mills, veterinary drugs, and meat and -

Rakhine State – Nutrition Information Analysis

RAKHINE STATE – NUTRITION INFORMATION ANALYSIS January – December 2014 INTRODUCTION The Rakhine state nutrition response aims to achieve 4 key objectives: Sector objectives 1. To reduce malnutrition-related deaths in girls and boys under-5 by ensuring access to quality life-saving interventions for management of acute malnutrition, guided by global standards; 2. Ensure access to key preventive nutrition services routinely provided by Government; 3. Ensure enhanced monitoring and analysis of nutrition situation, needs, and evolving vulnerabilities; 4. Improve cross sector and actor collaboration to address underlying factors of malnutrition. This report addresses the first and second objectives for which the sector is able to obtain information regularly though the Nutrition Information Systems (NIS) and monitor indicators on a monthly basis; Outcome level indicators 1. Percentage of girls and boys CURED of acute malnutrition 2. Percentage of girls and boys with acute malnutrition who DIED 3. Percentage of children under 5 years provided with vitamin A and deworming treatment routinely provided by government 4. Percentage of affected women provided with skilled breastfeeding counselling Activities Active and passive screening of children 6-59 months for acute malnutrition Treatment of severe and moderate acute malnutrition in children 6-59 months through provision of ready-to-use therapeutic or supplementary food, routine medicines, medical consultation and counselling for cases of severe acute malnutrition with infant and young child feeding support Micronutrient prevention and control (children/ PLW) Vitamin A supplementation and deworming Blanket supplementary feeding (children/ PLW) Organizations involved in response DoH, ACF, MHAA, SCI, UNICEF, WFP, MNMA Rakhine State nutrition information December 2014 1 1. -

Of the Rome Statute

ICC-01/19-7 04-07-2019 1/146 RH PT Cour Penale (/\Tl\) _ni _t_e__r an _t_oi _n_a_l_e �i��------------------ ----- International �� �d? Crimi nal Court Original: English No.: ICC-01/19 Date: 4 July 2019 PRE-TRIAL CHAMBER III Before: Judge Olga Herrera Carbuccia, Presiding Judge Judge Robert Fremr Judge Geoffrey Henderson SITUATION IN THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH / REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR PUBLIC With Confidential EX PARTE Annexes 1, 5, 7 and 8, and Public Annexes 2, 3, 4, 6, 9 and 10 Request for authorisation of an investigation pursuant to article 15 Source: Office of the Prosecutor ICC-01/19-7 04-07-2019 2/146 RH PT Document to be notified in accordance with regulation 31 of the Regulations of the Court to: The Office of the Prosecutor Counsel for the Defence Ms Fatou Bensouda Mr James Stewart Legal Representatives of the Victims Legal Representatives of the Applicants Unrepresented Victims Unrepresented Applicants (Participation/Reparation) The Office of Public Counsel for The Office of Public Counsel for the Victims Defence States’ Representatives Amicus Curiae REGISTRY Registrar Counsel Support Section Mr Peter Lewis Victims and Witnesses Unit Detention Section Victims Participation and Reparations Other Section Mr Philipp Ambach No. ICC-01/19 2/146 4 July 2019 ICC-01/19-7 04-07-2019 3/146 RH PT CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 5 II. LEVEL OF CONFIDENTIALITY AND REQUESTED PROCEDURE .................... 8 III. PROCEDURAL -

Climate Risk Assessment for Fisheries and Aquaculture Based Adaptation in Myanmar

######################################################### Climate risk assessment for fisheries and aquaculture based adaptation in Myanmar Prepared By: Mark Dubois, Kimio Leemans, Michael Akester, Shwu Jiau Teoh, Bethany Smith, Hsu Mon Aung, Tinzar Win Pyae Kyaw, May Hsu Mon Soe & KuMuDara Win Maung Table of Content Introduction............................................................................................................................................. 1 Fisheries in Myanmar: A Brief Overview ............................................................................................ 1 Problem Statement ............................................................................................................................. 2 Overview of the Climate Based Risk Assessment Within Myanmar ................................................. 3 Ayeyarwady Region ......................................................................................................................... 5 Yangon Region ................................................................................................................................. 6 Rakhine State ................................................................................................................................... 7 The 2014 IPCC Risk Assessment Framework ...................................................................................... 8 Methodology .........................................................................................................................................12 -

Rakhine State Production Date : 1St July 2015 Mangrove Coverage Evolution in Pauktaw Township 1988-2015

For Humanitarian Purposes Only MYANMAR - Rakhine State Production date : 1st July 2015 Mangrove Coverage Evolution in Pauktaw Township 1988-2015 Thea Hpyu Thar Yar Min Kan San Htoe Chaik Khaung Laung Ywar Haung Kan Bu Kan Chaung Wa Kyan Chaung Kone (Sin Tan Taung Thar Zay Ah Wa Shwe Taik Chan) Pyin Nga Swei Htaunt Nyaung Pin Zin Khin Thar Dar Mrauk-U Taung Taung Moe Tein Lel (Ku Pyun To (Rakhine) Lar Pone) Chin Thea Tan Taik Kan Pyin Pyin Hpet Kya Taung Poet Gyi Thu Htay Khaung Laung Total MangroveThin Coverage for Hin Kha Ei Thei Kone Thu Nge Tway Ma Ywar Thit Pone Tan Yaw Taw Soke Nga Pyi Chay Na Daung Nat Chaung Kin Seik Ah Lel Inn tYarhe Taw Township in 1988 and 2015 (ha) Kya Ywar Haung Ku Lar Ah Lel Chaung Kyauk Pan Zin Htaunt Kywe Cha Gyin Ku Lar Sin Gyi Bar Chaung Ywar Nge Tin Htu Let Wea Seik Maw Chay Ah Me Chaung Pyin Myit Nar Thar Yar Sar Taik Nat Chaung Chay Tat Yar Khin (Rakhine) Pyin Kone Ywar Thit Sin Gyi Ma Gyi Di Par Pyin (MSL) Chaung Thar Si Shwe Zin Daing Yon Ku Lar Myit Nar Thone Pat Mi Kyaung Kone Kyat Pone Chaing Wet Ma Tet Kya Thin Pone Yin Ye Kan Chaung (Middle) Sint Minbya Hpyu Yae Paik Pin Yin Ponnagyun Chaung Dar Khan Ah Wa Son Kyein Zay Ya Htaunt Gan Kya Chaung Bu Pin Kyun Wa Di Bar Bu Taung Nga Wet Gyi Kyun Chaung Taung Yin Yae Hpyu Yin Ye Ohn Hna Leik Taunt Chay Tha Pyay Nga/Wai (Ein Nga Tan Kan Chaung Thein Zee Pin Teit Su Kyun Ah Htoke Kan Thein Kan Shey Min) Pyin Ku Lar Taung Gyi Chay Thei Wet Hnoke Taung Chaung Met Ka Hpar Lar Yar Ah Lel14590 Lar Kya Thee Chaung Let Pan Kone Zee Auk Zee Yae Pauk Se Thone -

UNOSAT Analysis of Destruction and Other Developments in Rakhine State, Myanmar

UNOSAT analysis of destruction and other developments in Rakhine State, Myanmar 7 September 2018 [Geneva, Switzerland] Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 2 Data and Methods ................................................................................................................................... 2 Satellite Images and Processing .......................................................................................................... 2 Satellite Image Analysis ....................................................................................................................... 3 Fire Detection Data ............................................................................................................................. 5 Fire Detection Data Analysis ............................................................................................................... 6 Settlement Locations ........................................................................................................................... 6 Estimation of the destroyed structures .............................................................................................. 6 Results ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 Destruction Visible in Satellite Imagery ............................................................................................. -

Rakhine State, Myanmar

World Food Programme S P E C I A L R E P O R T THE 2018 FAO/WFP AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY MISSION TO RAKHINE STATE, MYANMAR 12 July 2019 Photographs: ©FAO/F. Del Re/L. Castaldi and ©WFP/K. Swe. This report has been prepared by Monika Tothova and Luigi Castaldi (FAO) and Yvonne Forsen, Marco Principi and Sasha Guyetsky (WFP) under the responsibility of the FAO and WFP secretariats with information from official and other sources. Since conditions may change rapidly, please contact the undersigned for further information if required. Mario Zappacosta Siemon Hollema Senior Economist, EST-GIEWS Senior Programme Policy Officer Trade and Markets Division, FAO Regional Bureau for Asia and the Pacific, WFP E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web www.fao.org Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web www.fao.org at the following URL address: http://www.fao.org/giews/ The Global Information and Early Warning System on Food and Agriculture (GIEWS) has set up a mailing list to disseminate its reports. To subscribe, submit the Registration Form on the following link: http://newsletters.fao.org/k/Fao/trade_and_markets_english_giews_world S P E C I A L R E P O R T THE 2018 FAO/WFP AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY MISSION TO RAKHINE STATE, MYANMAR 12 July 2019 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME Rome, 2019 Required citation: FAO. -

Job Announcement Training Officer - One Post Yangon

Job Announcement Training Officer - One Post Yangon The Lutheran World Federation (LWF) Myanmar is an international non-government organization serving the people of Myanmar since 2008 after Cyclone Nargis. Currently LWF is facilitating rights-based empowerment process in 34 villages of Mindat and 20 villages in Matupi Township, Chin State, 29 villages of Kyarinnseikgyi, Pharpun and Hlainbwe Townships in Kayin State and 21 villages in Ann Township, Rakhine State. 36 Women Groups in Pyapon, Dedaye and Twantay Townships are also being supported and accompanied technically for sustainability. LWF is also assisting the IDPs, host communities and nearby villages of Sittwe, Mrauk U, Ponna Kyun and Pauktaw Township in Rakhine State to improve children’s access to education. LWF also works with Camp Management Committees (CMC) of 8 camps in Sittwe and Pauktaw Townships. Mainstreaming community based psychosocial support; gender; environment; fire-safety and protection are integral part of the program. The working approach of LWF is Rights Based Empowerment and Integrated Programmatic Approaches. Livelihoods, Quality Services, Protection and Social Cohesion and Systems and Practices for Quality Programming are four main components of LWF Myanmar. The strategic objectives of LWF are Communities have increased access to livelihoods and income generating opportunities, Communities have improved access to quality basic services (including basic infrastructures: roads, water, sanitation, electricity; education and healthcare) through their active engagement and Right holders, especially women, are empowered in managing their individual, household and village development through accessing their rights and entitlements. Its values and principles such as Dignity, Human Rights and Justice, Compassion and Commitment, Inclusion and Diversity, Meaningful Participation, Transparency and Accountability, Humanitarian Principles, Gender Justice and Climate Change guide the work. -

WHO/WHAT/WHERE - Agriculture Northern Rakhine State - Buthidaung, Maungdaw, Rathedaung Townships

Myanmar Information Management Unit WHO/WHAT/WHERE - Agriculture Northern Rakhine State - Buthidaung, Maungdaw, Rathedaung Townships BANGLADESH Bauk Shu Ye Hpweit Aung San Ya Bway 1 1 CHIN STATE Kyaung Kha Maung Na Hpay Thit Tone Nar Hlaing Thi Seik 1 Gwa 1 2 Son Nan 2 Ya r Kai ng Nga 2 Ya nt Cha ung 2 Ta Man Thar 2 Ya e Nauk Ngar Thar Kyaung Taung Thet Kaing Nyar Pa Da Kar 2 1 2 Mee Taik Ywar Pa Da Kar 1 Thit Day War San Kar 3 Nar Li Pin Yin 2 Kun Thee Min Gyi 1 Pin (Tu Lar Myo Wet Kyein 1 Tu Li) Mi 4 1 Chaung 1 Kyun Done Goke Myaw Pauk Paik (Aung 1 Pi Chaung Seik Pyin) 1 1 3 Ya e Kyein Chaung 3 Buthidaung Township Twin Ta Ya Laung Don Pyin Myauk Gu 4 1 Ye (a) Pan Be Chaung 1 2 Doe Sa Bai Tan Kone Ngar Sar Yin 1 3 Ah Htet Kyu Ma Pyu Ma 5 Kyaung 1 Kyet Yoe Pyin Taung Zee Hton 1 Yae Myet Taung 5 2 1 Ngan Chaung 4 Pwint Hpyu Hpar Wut Nga Yant Yae Khat Chaung (Ywar Chaung Chaung Chaung Gwa Thit) Inn 2 1 Kyar Son Myaw 4 Chaung Thin Ga Gaung 1 Taung 3 Net Taun g 1 3 1 Mee Chaung Maung Mee Hna Ma Khaung Chaung Maungdaw Township 4 Laung Swea Dar Zay Chaung Paing 5 2 1 Nga Sa Yar Tha Kyin Tauk 4 Chin Yet Ok e 4 Tha Kyauktaw 1 Thet Kyee Maung Mar Kay Pyin Kan Pyin Tat Min Chaung Gyi Htaunt 3 1 3 2 4 Zin Paing Kun Taing (a) Zee Pin Ywar Nyar Kyauk Hpyu Taung Taung Nwar Yon Ma Tha Yet 2 3 Nan 4 Taun g 3 Ya r Kin Pyin 3 Let Wea Det Kone Ma Nu Chaung Pu Zun Chaung Let Wea 2 1 Bat Kar Gone Nar Det Pyin 3 3 Da Pyu 3 Shey Ka Kyet Bet Chaung Aye Tar 4 Kan Pyin Ywet Shwe Zar Myo 2 Li Yar 3 Nyo Kin Taung Kat Pa Kaung Thu Gyi Ka 2 2 Kyet Bet Taung (a) Kyar -

Village Tracts of Northern Rakhine State (Buthidaung, Maungdaw, Rathedaung Townships ) N N ' ' 0 0

Myanmar Information Management Unit Village Tracts of northern Rakhine State (Buthidaung, Maungdaw, Rathedaung Townships ) N N ' ' 0 0 3 92°30'E 93°0'E 3 ° ° 1 1 2 2 BANGLADESH Tat Chaung In Tu Lar CHIN STATE Kar Lar Day Hpet Bauk Shu Ye Aung San Hpweit Ya Bway Paletwa Kyaung (! Samee Na Hpay !( Hlaing Thi Kha Maung Seik Ba Da Kar Nan Yar Thit Tone Kaing Nar Gwa Nga Yant Son Mee Taik Chaung (Taungpyoletwea Sub-township) Ta Man Thar Yae Nauk Taungpyoletwea Ngar Thar !( Thet Kaing Kha Maung Pa Da Kyaung Taung Tin May Nyar Chaung Taung Pyo Let Yar Kar Day (Taungpyoletwea War Nar Li Sub-township) Thea Chaung (Taungpyoletwea Pa Da Kar Kun Thee Pin Sub-township) San Kar Ywar Thit (Taungpyoletwea Pin Yin Sub-township) Min Gyi (Tu Lar Wet Kyein Laung Yon Leik Ya Tu Li) Done Paik Kyun Pauk Goke Pi (Taungpyoletwea (Aung Seik Sub-township) Kyun Pauk Sin Oe Pyin) (Taungpyoletwea Kyauk Chaung Sub-township) Kyein Chaung (Taungpyoletwea Myaw Chaung Sub-township) Laung Don Ta Ya Gu Zee Pin Chaung Myauk Ye (a) (Taungpyoletwea Pan Be Chaung Sub-township) Sa Bai Kone Ah Htet Pyu Ma Ka Yin Ma Nyin Tan Pyu Ma Doe Ngar Sar Kyu Kyaung Myo Tan Zee Hton Pyu Ma Ka Taung Nyin Tan Thit Kyet Yoe Pyin Aw Ra Ma (a) Kat Pa Kaung Yae Yee Chaung Nga Khu Ya Ngan Chaung N Pyin Hla N ' Nga Khu Ya Myet Taung Nga Yant ' 0 0 ° U Shey Kya Pwint Hpar Wut Chaung ° 1 Hpyu Chaung Ba Da Nar 1 2 Chan Chaung Thin Ga Net 2 Kyar Gaung (Ywar Thit) Pyin Inn Chaung Taung Myaw Oke Taung Yae Twin Yae Khat Taung Mee Chaung Mee Kyun Chaung Gwa Son Maung Khaung Chaung Zay Ywet Nyoe Dar Gyi Zar