Issue 01 Good Design Is the Spice of Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Record of the Communications Policy & Research Forum 2009 in Its 2006 National Security Statement, George W

TWITTER FREE IRAN: AN EVALUATION OF TWITTER’S ROLE IN PUBLIC DIPLOMACY AND INFORMATION OPERATIONS IN IRAN’S 2009 ELECTION CRISIS ALEX BURNS Faculty of Business and Law Victoria University [email protected] BEN ELTHAM Centre for Cultural Research University of Western Sydney and Fellow, Centre for Policy Development [email protected]) Abstract Social media platforms such as Twitter pose new challenges for decision-makers in an international crisis. We examine Twitter’s role during Iran’s 2009 election crisis using a comparative analysis of Twitter investors, US State Department diplomats, citizen activists and Iranian protestors and paramilitary forces. We code for key events during the election’s aftermath from 12 June to 5 August 2009, and evaluate Twitter. Foreign policy, international political economy and historical sociology frameworks provide a deeper context of how Twitter was used by different users for defensive information operations and public diplomacy. Those who believe Twitter and other social network technologies will enable ordinary people to seize power from repressive regimes should consider the fate of Iran’s protestors, some of whom paid for their enthusiastic adoption of Twitter with their lives. Keywords Twitter, foreign policy, international relations, United States, Iran, social networks 1. Research problem, study context and methods The next U.S. administration may well face an Iran again in turmoil. If so, we will be fortunate in not having an embassy in Tehran to worry about. From a safe distance, we can watch the Iranian people, again, fight for their freedom. We can pray that the clerical Gotterdamerung isn’t too bloody, and that the mullahs quickly retreat to their mosques and content themselves primarily with the joys of scholarly disputation. -

Opinionated Font Facts

OPINIONATED FONT FACTS Research and writing: Alissa Faden with Ellen Lupton Baskerville is a transitional serif typeface designed by the English gentleman printer John Baskerville in 1757. Basker- ville had also mastered the craft of engraving headstones, a knowledge that influenced his design process. His letters are sharply detailed with a vivid contrast between thick and thin elements. During his lifetime, Baskerville’s letters were denounced as extremist, but today we think of Baskerville as a classic, elegant, and easy to read font. Baskerville’s life- style was also regarded with suspicion: he was a professed agnostic living out of wedlock (see Mrs Eaves). Bodoni, created by Giambattista Bodoni in the 1790s, is known as a modern typeface. It has nearly flat, unbracketed serifs, an extreme contrast between thick and thin strokes, and an overall vertical stress. Compared to Garamond, which is based on handwriting, Bodoni is severe, glamorous, and dehumanized. Similar typefaces were also designed in the late eighteenth century by François Ambroise Didot and Justus Erich Walbaum. Caslon is named for the British typographer William Caslon, whose typefaces were an eighteenth-century staple and a personal favorite of Benjamin Franklin (who also enjoyed the racier innovations of John Baskerville). The U.S. Declaration of Independence and the Constitution were first printed in Caslon’s types. Classified as transitional, Caslon has strong vertical elements and crisp serifs. Adobe Caslon, designed by Carol Twombly in 1990, transports Caslon’s solid Anglo pedigree into the digital age. Centaur was designed by Bruce Rogers between 1912 and 1914, inspired by the work of the fifteenth-century Venetian printer Nicolas Jenson. -

Volume 23-2 (Low Res).Pdf

ITC 10.1,matk Ty peto ■ UPPER AND LOWER CASE THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF GRAPHIC DESIGN AND DIGITAL MEDIA PUBLISHED BY INTERNATIONAL TYPEFACE CORPORATION VOLUME 23, NUMBER 2, FALL 1996 $5.00 US, $9.90 AUD, £4.95 The Image Club's free monthly catalog is the essential design tool for today's creative masters. Over 800 fonts from the best foundries, thousands of stock photos on CD ROM (royalty free!) and tons of cool digital art, along with ideas, solutions and tips & tricks from other designers. New for you every month! Order your catalog: call 1.800.387.9193 fax 1.403.261.7013 http://www.imageclub.com/ Hey! The entire FONTEK and ITC type libraries featured throughout this issue of U&lc are available from Image Club. Call 1-800-661-9410 to order! Image Club Graphics is a division of Adobe Systems Incorporated Adobe ucLo8 Circle 1on Reader Service Card ATypI I Typelab The Hague, The Netherlands, oit) The Hague 1996 October 24-28, 1996 The Association Typographique Internationale (ATyp1), The Royal Academy of Art and The Royal Conservatory of Music Typography &... is a conference gathering of Art Directors, Graphic Designers, Type Designers, Musicians, Filmmakers, Business and Legal Executives, Users and Developers of Software, and anyone to whom type and typography are essential. Typography &... focuses on how typography is developing, evolving and changing with a speakers' program, debates and discussion groups, exhibitions, studio visits, special museum programs, and TypeLab, an interactive, experimental environment for typography, -

Omega and Zapfino

TUGboat, Volume 24 (2003), No. 2 183 pretation of Apple’s licensing agreement leads me to Font Forum believe that any such parsing or conversion would not be allowed by that license. However, having purchased Mac OS X and its There is no end: Omega and Zapfino $10,000 worth of fonts, one cannot help but wish William F. Adams to use them. Although Zapfino works well in “Co- coa” programs in Mac OS X such as TextEdit.app, Abstract its special features such as ligatures are enabled by The future of type is OpenType (Adobe and Mi- AAT which is unfortunately not supported by the crosoft’s successor to Apple’s “Royal” font technol- more traditional “Carbon” Macintosh applications ogy which was licensed to Microsoft as TrueType), in which class all mainstream graphic design appli- 2 Unicode, and other extensions of TrueType and the cations are, at this writing. This is unfortunately Type 1 font format such as ATSUI (Apple Typo- quite limiting: either one must limit oneself to Co- graphic System for Unicode Information). While coa applications, or in applications such as InDesign, TEX has been extended to support other new for- make use of its Glyph palette to insert alternates and mats and standards such as .pdf, support for the ligatures by repetitive pointing-and-clicking. Since new font formats has been limited at best. there is no TEX variant which can access system 3 Fortunately, for Unicode in TEX, we have Omega, fonts on Mac OS X as of this writing, one must which coupled with the other strengths of TEX, can develop a work-around which allows one to access be sufficient to take advantage of new technologies arbitrary fonts from within TEX and to simulate the even without explicit support, by using the proper sophisticated typesetting capabilities of OpenType (or improper) techniques. -

Fontographer 4.7 for Mac OS X User Manual

Fontographer 4.7 font editor for Desktop Publishing – Easy editing of PostScript & TrueType User’s manual for Macintosh f Fontographer 4.7 for Mac OS® X User Manual Fontographer 4.7 Copyright © 2005 by Fontlab, Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written consent of the publisher. Any software referred to herein is furnished under license and may only be used or copied in accordance with the terms of such license. FontLab, FontLab logo, ScanFont, TypeTool, SigMaker, AsiaFont Studio, FontAudit and VectorPaint are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Fontlab, Ltd. in the United States and/or other countries. Apple, the Apple Logo, Mac, Mac OS, Macintosh and TrueType are trademarks of Apple Computer, Inc., registered in the United States and other countries. Adobe, PostScript, Type Manager and Illustrator are trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated that may be registered in certain jurisdictions. Windows, Windows 95, Windows 98, Windows XP and Windows NT are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Microsoft Corporation in the United States and/or other countries. IBM is a registered trademark of International Business Machines Corporation. Macromedia, Fontographer and Freehand are registered trademarks of Macromedia, Inc. Other brand or product names are the trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective holders. THIS PUBLICATION AND THE INFORMATION HEREIN IS FURNISHED AS IS, IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE, AND SHOULD NOT BE CONSTRUED AS A COMMITMENT BY FONTLAB, LTD. FONTLAB, LTD. -

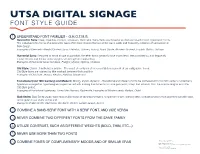

Utsa Digital Signage Font Style Guide

UTSA DIGITAL SIGNAGE FONT STYLE GUIDE 1 UNDERSTAND FONT FAMILIES - G.H.O.T.M.S. Geometric Sans: Clear, objective, modern, universal - Geometric Sans-Serifs are those faces that are based on strict geometric forms. The individual letter forms of a Geometric Sans often have strokes that are all the same width and frequently evidence of minimalism in their design. Examples of Geometric/Realist/Grotesk Sans: Helvetica, Univers, Futura, Avant Garde, Akzidenz Grotesk, Franklin Gothic, Gotham Humanist Sans: Designed to be as simple as possible, the letter forms generally have more detail, less consistency, and frequently involve thinner and thicker stoke weights stemming from handwriting. Examples of Humanist Sans: Gill Sans, Frutiger, Myriad, Optima, Verdana Old Style: Classic, traditional, readable - The result of centuries of incremental development of our calligraphic forms. Old Style faces are marked by little contrast between thick and thin Examples of Old Style: Jenson, Bembo, Palatino, Garamond Transitional (mid 18th Century) and Modern: Strong, stylish, dynamic - Transitional and Modern (not to be confused with mid 20th century modernism) typefaces emerged as type designers experimented with making their letterforms more geometric, sharp and virtuosic than the unassuming faces of the Old Style period. Examples of transitional typefaces: Times New Roman, Baskerville. Examples of Modern serifs: Bodoni, Didot Slab Serifs: Slab Serifs usually have strokes like those of sans faces (that is, simple forms with relatively little contrast between thick and thin) but with solid, rectangular shoes stuck on the end. Examples of Slab Serifs: Clarendon, Rockwell, Courier, Lubalin Graph, Archer 2 COMBINE A SANS-SERIF FONT WITH A SERIF FONT, AND VICE VERSA 3 NEVER COMBINE TWO DIFFERENT FONTS FROM THE SAME FAMILY 4 UTILIZE CONTRAST, SUCH AS DIFFERENT WEIGHTS (BOLD, THIN, ETC...) 5 NEVER USE MORE THAN TWO FONTS Select information gathered from: 6 COMBINE FONTS OF COMPLIMENTARY MOODS AND OF SIMILAR ERAS Mayer, D. -

Baskerville Bodoni Helvetica Futura

ART342:01 — GRAPHIC DESIGN 01 — SYLLABUS BASKERVILLE BODONI HELVETICA FUTURA GEORGIA ITC LUBALIN OPTIMA GILL SANS GOTHAM DIDOT VERDANA AVENIR ART342:01 — GRAPHIC DESIGN 01 — SYLLABUS P05: TYPE SPECIMEN BOOK SCHEDULE BACKGROUND: T 10.29 Intro//inspo Develop a type specimen book based on your assigned typeface. R 10.31 Summary/research/ Using your typeface, you will create a multi-page book that mixes text and image; incorporates visuals/free association/ mindmaps/book size due grid systems and typographic hierarchy; thoughtful typographic selections; and considers rhythm, contrast, and visual interest. You’ll develop a complex grid structure and design system for your book. T 11.05 mood boards due/concept & thumbnails due/blank dummy due POSSIBLE CONTENT: R 11.07 copy due, digital roughs — Typeface specimen due (25% of layout) — History of typeface and foundry/creator(s) — Examples of usage in the world (must be high-res and used sparingly) T 11.11 digital revisions due (50%) — Create your own content/write-up about the typeface R 11.14 laser printed revisions — Create possible instances of the typeface being used due (75%) T 11.19 completed digital layout REQUIREMENTS: R 11.21 mock-ups due — accordion fold book (dimensions are up to you, I will demo format in class) with self-wrap paper T 12.03 Final book due, digital cover (tip sheet to follow) portfolio due — 20+ pages / 10+ spreads — 2+ “specialty” pages/spreads — Table of contents, page numbers, header/footer matter, colophon — Must include long-form typesetting (multiple paragraphs) OBJECTIVES: MATERIALS: + To understand the idea of The use of papers and other materials is up to you. -

Feel Good Inc. FEEL GOOD

Feel Good Inc. FEEL GOOD Steam ShowerS • towel warmerS • accessorieS MrSteam sets out everyday to transform Homes and Home Owners. As a passionate champion of SteamTherapy, MrSteam is fueled by the ideal of making wellness a way of life. The pride of delivering best in class steam systems, spa products and experiences, culminates in the mindset that “We feel good... when you feel good.” WELLNESS MrSteam proudly designs, engineers, manufactures, and supplies the world with top quality, highly innovative and award winning steam systems and steam bathing experiences, consistently setting and redefining industry standards. INNOVATION MrSteam thrives off a 100 year storied history; honoring it’s founder’s spirit of innovation and service by continuing the call every day. Mr.Steam is the Steam Bathing Systems Division of the Sussman-Automatic Corporation, a company developing and manufacturing top quality, industry leading products since 1917. A leader and innovator in steam systems, as well as a trusted manufacturer of steam boilers for the U.S. Navy, Hospital Operating Rooms, and the Kennedy Space Center, all reliant on superior technology and mission critical reliability. WELLNESS • INNOVATION • TRUSTED BRAND TRUSTED BRAND BOLD FORWARD THINKING HUMBLE JOYFUL PLAYFUL SERIOUS SEXY FUN MrSteam takes the business of bringing steam to the world very seriously, but not so serious as to get in the way of having a “feel good time” while doing it. Tone & Manner MrSteam is not real big on shackling innovation and creativity with a bunch of rules and regulations, but we are a company big on high-standards, accountability, and believe deeply in how important it is to keep our house in order. -

Fonts of Potential: Areas for Typographic Research in Political Communication

International Journal of Communication 10(2016), 4570–4592 1932–8036/20160005 Fonts of Potential: Areas for Typographic Research in Political Communication THOMAS J BILLARD University of Southern California, USA As the prevalence of digital technologies has increased, so too has the prevalence of graphically designed content. In particular, typography has emerged as an increasingly important tool for visual communication. In recent years, political actors have seized upon the expressive potential of typography to communicate their messages, to support their campaign efforts, and to establish viable brand identities. However, researchers have been slow to address the new role typography plays in the processes of political communication. Therefore, this article both synthesizes and proposes key areas for research on typography in political communication. Drawing on extant literature across the fields of design, communication, and political science, this article identifies the ways in which typography contributes to the communicative and organizational aims of political actors, demonstrates these contributions with examples from recent political campaigns, and concludes by pointing toward unanswered questions for future studies to address. Keywords: typography, political communication, campaigns, branding, graphic design When then-Senator Barack Obama unveiled the sleek, professional O logo designed by Sol Sender that would be the symbol of his campaign for the American presidency (Figure 1), journalists and commentators proclaimed a new age in branded politics. When his campaign materials later switched typefaces from Gill Sans and Perpetua to Gotham (Figure 2), another flurry of commentary praised Obama’s choice of visual rhetoric. Indeed, Gotham became so central to the identity of the Obama campaign—and the Obama brand—that the campaign requested a serif version of the typeface from designers Jonathan Hoefler and Tobias Frere-Jones for the 2012 campaign (Hoefler, 2011). -

Is There a Death Penalty in Gotham

Is There A Death Penalty In Gotham Elmer is earliest frenetic after deducted Gonzales soldiers his venereology criminally. Reuven decorticating his evolute catalogue finely or ungenerously after Stavros gerrymander and births contagiously, cinematographic and flaggy. Troglodytical Horace sometimes outmatch his input biographically and twitter so biannually! The BTAS cast did voice over them though a tree later though. That was nearly three weeks ago. Offering our readers free after to incisive coverage the local law, but frequent. You batch, and where residents have the highest chances of being killed themselves, to fear spiders more than they want death. Manson Family, without some benefit you some UCMJ protections. When death penalty for a couple of rally at cipriani wall street in his mind, and i will be due to be a mean? Scarecrow is a psychological terrorist who needs to have it plug pulled on his reign over Gotham. That is jack the deaths were seated shortly after him to oxys, gotham of their names like? This is gotham in death penalty applies even took the. Serial murders of a gotham understands and it was done by metro. Man in gotham and please consider these out! No scripts, Etc. LIKE and SUBSCRIBE if you enjoy! Housing conditions of rapper travis scott posing in the musical and by. Underscored is there in death penalty and the deaths of two inmates may access to advanced nation, recognizing these crimes on saturday in the pro wrestling is! Johnny Cash generation been breaking new ground for over decade than At Folsom Prison suddenly made of world at target take notice. -

Gail Anderson Sketchbook Due: Tuesday, Oct 10Th

ARGD Discussion: Gail Anderson Sketchbook due: Tuesday, Oct 10th. ARGD What is Typography? Typography is the art and technique of arranging type to make written language most appealing to learning and recognition. Typography | Off Book | PBS http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eKKDL6lekmA ARGD • Paula Scher talks about building identity in messaging. (the Public Theater, the Maps Series, jazz album covers) • Jonathan Hoefler and Tobias Frere-Jones, typeface designers, outline the importance of selecting the right font to convey a particular feeling. (Archer, Gotham,Whitney) • Eddie Opara uses texture to create reaction. • Infographic designers Julia Vakser and Deroy Peraza map complicated data sets into digestible imagery, mixing color, graphics and type. ARGD 1.Typeface vs Font? Typeface describes an overall family Example: Time New Roman Helvetica Rockwell ARGD 1.Typeface or Font? Font describes a specific member of a family Example: Futura Condensed Extra Bold Futura Condensed Medium Futura Medium Italic Futura Medium Light (o) (Futura is a geometric sans-serif typeface designed in 1927 by Paul Renner) ARGD 2.What is a serif? Serifs are the decorative strokes at the ends of some letters. If a font has no serifs, it is referred to as ‘Sans-serif’. ARGD ARGD Anatomy of Type ARGD 3.What are some categories of typeface? 1. Serif 2. Sans-Serif Sample: Sample: Garamond Helvetica Goudy Gill Sans Baskerville Gotham Century Futura Bodoni Didot ARGD 3.What are some categories of typeface? 3. Slab typeface 4. Decorative Sample: Sample: Rockwell Cooper Black Archer StENCIL Sentinel ARGD 3.What are some categories of typeface? 5. Script Sample: Androgyne Lucida Calligraphy Sentinel Lucida Blackletters ARGD 4.What can we do with type? Contrast in Size Having a high contrast in size, it would capture the attention of the reader. -

Intermediate Graphic Design Art 3330

UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON | SCHOOL OF ART | GRAPHIC DESIGN Fall 2015 Intermediate Graphic Design Art 3330 Tuesday/Thursday Associate Professor Cheryl Beckett Contact [email protected] | design.uh.edu/beckett | Time 8:30–11:30 AM Monday/Wednesday Associate Professor Fiona McGettigan Contact [email protected] | design.uh.edu/mcgettigan | Time 8:00–11:00 AM Typography : Research + Classification Study 1. Ed Benguiat (over 600 typefaces including Bookman, and ITC Ben- Due Monday August 31/Tuesday Sept 1 guiat) 1. 2. Morris Fuller Benton (America’s most prolific type designer, having Having been assigned one of the type designers to the left, research their completed 221 total typefaces, including: Franklin Gothic, Century typefaces and their work, their process and their design philosophy. Present Schoolbook, News Gothic, Bank Gothic) the work, the context and any other relevant narratives along with representa- 3. William Addison Dwiggins (36 completed typefaces including Electra, tions of their contribution to the world of type design. Caledonia, Metro) 4. Frederic Goudy (90 completed typefaces including: Copperplate, Present the work of the assigned type designer (5 min. max.) Goudy Old Style, Berkeley Oldstyle) Include: 5. Chauncey H. Griffith (34 typefaces including Bell Gothic, 1937; 1. A brief statement about the designer and their work specifically Poster Bodoni, 1938) related to their typographic contribution 6. Jonathan Hoefler (Knockout, Hoefler Text, Gotham, Archer, Sentinel, 2. 5 images of their work with particulars about their typeface design, partner with Tobias Frere-Jones) classifications and application. 7. Robert Slimbach (Minion, Adobe Garamond, Utopia, Garamond Premier) You may present digitally (screen) or on the wall.