Typeface Connotation Matias Ferrari Purdue University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supreme Court of the State of New York Appellate Division: Second Judicial Department

Supreme Court of the State of New York Appellate Division: Second Judicial Department A GLOSSARY OF TERMS FOR FORMATTING COMPUTER-GENERATED BRIEFS, WITH EXAMPLES The rules concerning the formatting of briefs are contained in CPLR 5529 and in § 1250.8 of the Practice Rules of the Appellate Division. Those rules cover technical matters and therefore use certain technical terms which may be unfamiliar to attorneys and litigants. The following glossary is offered as an aid to the understanding of the rules. Typeface: A typeface is a complete set of characters of a particular and consistent design for the composition of text, and is also called a font. Typefaces often come in sets which usually include a bold and an italic version in addition to the basic design. Proportionally Spaced Typeface: Proportionally spaced type is designed so that the amount of horizontal space each letter occupies on a line of text is proportional to the design of each letter, the letter i, for example, being narrower than the letter w. More text of the same type size fits on a horizontal line of proportionally spaced type than a horizontal line of the same length of monospaced type. This sentence is set in Times New Roman, which is a proportionally spaced typeface. Monospaced Typeface: In a monospaced typeface, each letter occupies the same amount of space on a horizontal line of text. This sentence is set in Courier, which is a monospaced typeface. Point Size: A point is a unit of measurement used by printers equal to approximately 1/72 of an inch. -

Anatomy of the Letter A

Anatomy Of The Letter A When Emmett tetanises his continuants telescopes not ornately enough, is Skipper tippier? Intravenous Etienne number her argillites so zealously that Quinlan quantize very diamagnetically. How colligative is Meade when uncomposable and deciduous Broddy overshadow some consolidations? For the anatomy of letter a science foundation upon a document Shoulder of all numerals were so you remember your next generation of the above and emphasis in this email builders for example, there are involved in. The of anatomy. Redbubble digital design projects design axis results of a business must also referred to. This the curved stroke of the headline and glands or two angled strokes. Consider a playful feel when death you temporary access this username is of anatomy and followers on this part of reading. Opening or partially enclosed negative space within the cavity beneath the. Get the anatomy of letter a character make this research, author letters of a few letters have shown me the main trunk of the line of an identifying factor for by. In more appealing what goes above, giving it also go over time of anatomy type design has precious little bit extra? Notify me now for your website built all part of character can send this is specific part of two strokes of. In anatomy of measure the letter, newspapers and love magazine as possible only the anatomy and weight for your site may receive sensitive? Your work with input from a high quality digital projects. Hairline is usually curved transition or diagonal stroke or more letter forms to try again, or delete and. -

Record of the Communications Policy & Research Forum 2009 in Its 2006 National Security Statement, George W

TWITTER FREE IRAN: AN EVALUATION OF TWITTER’S ROLE IN PUBLIC DIPLOMACY AND INFORMATION OPERATIONS IN IRAN’S 2009 ELECTION CRISIS ALEX BURNS Faculty of Business and Law Victoria University [email protected] BEN ELTHAM Centre for Cultural Research University of Western Sydney and Fellow, Centre for Policy Development [email protected]) Abstract Social media platforms such as Twitter pose new challenges for decision-makers in an international crisis. We examine Twitter’s role during Iran’s 2009 election crisis using a comparative analysis of Twitter investors, US State Department diplomats, citizen activists and Iranian protestors and paramilitary forces. We code for key events during the election’s aftermath from 12 June to 5 August 2009, and evaluate Twitter. Foreign policy, international political economy and historical sociology frameworks provide a deeper context of how Twitter was used by different users for defensive information operations and public diplomacy. Those who believe Twitter and other social network technologies will enable ordinary people to seize power from repressive regimes should consider the fate of Iran’s protestors, some of whom paid for their enthusiastic adoption of Twitter with their lives. Keywords Twitter, foreign policy, international relations, United States, Iran, social networks 1. Research problem, study context and methods The next U.S. administration may well face an Iran again in turmoil. If so, we will be fortunate in not having an embassy in Tehran to worry about. From a safe distance, we can watch the Iranian people, again, fight for their freedom. We can pray that the clerical Gotterdamerung isn’t too bloody, and that the mullahs quickly retreat to their mosques and content themselves primarily with the joys of scholarly disputation. -

Steganography in Arabic Text Using Full Diacritics Text

Steganography in Arabic Text Using Full Diacritics Text Ammar Odeh Khaled Elleithy Computer Science & Engineering, Computer Science & Engineering, University of Bridgeport, University of Bridgeport, Bridgeport, CT06604, USA Bridgeport, CT06604, USA [email protected] [email protected] Abstract 1. Substitution: Exchange some small part of the carrier file The need for secure communications has significantly by hidden message. Where middle attacker can't observe the increased with the explosive growth of the internet and changes in the carrier file. On the other hand, choosing mobile communications. The usage of text documents has replacement process it is very important to avoid any doubled several times over the past years especially with suspicion. This means to select insignificant part from the mobile devices. In this paper we propose a new file then replace it. For instance, if a carrier file is an image Steganogaphy algorithm for Arabic text. The algorithm (RGB) then the least significant bit (LSB) will be used as employs some Arabic language characteristics, which exchange bit [4]. represent as small vowel letters. Arabic Diacritics is an 2. Injection: By adding hidden data into the carrier file, optional property for any text and usually is not popularly where the file size will increase and this will increase the used. Many algorithms tried to employ this property to hide probability being discovered. The main goal in this data in Arabic text. In our method, we use this property to approach is how to present techniques to add hidden data hide data and reduce the probability of suspicions hiding. and to void attacker suspicion [4]. -

A Catalogue of the Wood Type at Rochester Institute of Technology David P

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses Thesis/Dissertation Collections 11-1-1992 A Catalogue of the wood type at Rochester Institute of Technology David P. Wall Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Wall, David P., "A Catalogue of the wood type at Rochester Institute of Technology" (1992). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Thesis/Dissertation Collections at RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. School ofPrinting Management and Sciences Rochester Institute ofTechnology Rochester, New York Certificate ofApproval Master's Thesis This is to Certify that the Master's Thesis of David P. Wall With a major in Graphic Arts Publishing has been approved by the Thesis Committee as satisfactory for the thesis requirement for the Master ofScience degree at the convocation of DECEMBER 1992 Da,e Thesis Committee: David Pankow Thesis Advisor Marie Freckleton Graduate Program Coordinator George H. Ryan Direcmr or Designa[e A Catalogue of the Wood Type at Rochester Institute of Technology by David P. Wall A thesis project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the School of Printing Management and Sciences in the College of Graphic Arts and Photography of the Rochester Institute ofTechnology November 1992 Project Advisor: Professor David Pankow Introduction type,' When Adobe Systems introduced in 1990 their first digital library of 'wood the event marked the latest step forward in a tradition dating back to 1828, when Darius Wells, ofNew Wells' York City, perfected the equipment and techniques needed to mass produce wood type. -

CLASS: Working with Students with Dysgraphia

A Quick Guide to Working with Students with Dysgraphia Characteristics of the Condition This is a general term is used to describe any of several distinct difficulties in producing written language. These problems may be developmental in origin or may result from a brain injury or neurological disease. They often occur with other difficulties (e.g., dyslexia), but may be encountered in isolation. • Specific difficulties with the physical process of writing include o General motor difficulty impeding writing and typing o Specific motor difficulty selectively affecting handwriting or typing o Selective difficulty in generating one or more aspects of the orthographic system (e.g., print vs. cursive forms; upper case vs. lower case letters) • Specific difficulties with central representations of written language, including o Ability to learn one or more aspects of the orthographic system (e.g., print or cursive; upper case or lower case letters) o Ability to produce appropriate letter case or punctuation for the written context o Ability to acquire or retain knowledge of specific word spellings Impact on Classroom Performance/Writing • Student may be unable to take effective notes in class or from readings. • Writing by hand may be slow and effortful, resulting in diminished content in papers and essays in comparison with the student’s knowledge. • Legibility of written work may be poor, becoming increasingly worse from the beginning to the end of the document. • Capitalization and punctuation errors inconsistent with student’s linguistic skills may be seen. • Spelling may be inaccurate and/or inconsistent. • Vocabulary used in writing may be significantly restricted in comparison to the student’s reading or spoken vocabulary (may be due to concerns about spelling accuracy). -

Optical Character Recognition - a Combined ANN/HMM Approach

Optical Character Recognition - A Combined ANN/HMM Approach Dissertation submitted to the Department of Computer Science Technical University of Kaiserslautern for the fulfillment of the requirements for the doctoral degree Doctor of Engineering (Dr.-Ing.) by Sheikh Faisal Rashid Dean: Prof. Dr. Klaus Schneider Thesis supervisors: Prof. Dr. Thomas Breuel, TU Kaiserslautern Prof. Dr. Andreas Dengel, TU Kaiserslautern Chair of supervisory committee: Prof. Dr. Karsten Berns, TU Kaiserslautern Kaiserslautern, 11 July, 2014 D 386 Abstract Optical character recognition (OCR) of machine printed text is ubiquitously considered as a solved problem. However, error free OCR of degraded (broken and merged) and noisy text is still challenging for modern OCR systems. OCR of degraded text with high accuracy is very important due to many applications in business, industry and large scale document digitization projects. This thesis presents a new OCR method for degraded text recognition by introducing a combined ANN/HMM OCR approach. The approach provides significantly better performance in comparison with state-of-the-art HMM based OCR methods and existing open source OCR systems. In addition, the thesis introduces novel applications of ANNs and HMMs for document image preprocessing and recognition of low resolution text. Furthermore, the thesis provides psychophysical experiments to determine the effect of letter permutation in visual word recognition of Latin and Cursive script languages. HMMs and ANNs are widely employed pattern recognition paradigms and have been used in numerous pattern classification problems. This work presents a simple and novel method for combining the HMMs and ANNs in application to segmentation free OCR of degraded text. HMMs and ANNs are powerful pattern recognition strategies and their combination is interesting to improve current state-of-the-art research in OCR. -

Classifying Type Thunder Graphics Training • Type Workshop Typeface Groups

Classifying Type Thunder Graphics Training • Type Workshop Typeface Groups Cla sifying Type Typeface Groups The typefaces you choose can make or break a layout or design because they set the tone of the message.Choosing The the more right you font know for the about job is type, an important the better design your decision.type choices There will are be. so many different fonts available for the computer that it would be almost impossible to learn the names of every one. However, manys typefaces share similar qualities. Typographers classify fonts into groups to help Typographers classify type into groups to help remember the different kinds. Often, a font from within oneremember group can the be different substituted kinds. for Often, one nota font available from within to achieve one group the samecan be effect. substituted Different for anothertypographers usewhen different not available groupings. to achieve The classifi the samecation effect. system Different used by typographers Thunder Graphics use different includes groups. seven The major groups.classification system used byStevenson includes seven major groups. Use the Right arrow key to move to the next page. • Use the Left arrow key to move back a page. Use the key combination, Command (⌘) + Q to quit the presentation. Thunder Graphics Training • Type Workshop Typeface Groups ����������������������� ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������ -

Typeface Classification Serif Or Sans Serif?

Typography 1: Typeface Classification Typeface Classification Serif or Sans Serif? ABCDEFG ABCDEFG abcdefgo abcdefgo Adobe Jenson DIN Pro Book Typography 1: Typeface Classification Typeface Classification Typeface or font? ABCDEFG Font: Adobe Jenson Regular ABCDEFG Font: Adobe Jenson Italic TYPEFACE FAMILY ABCDEFG Font: Adobe Jenson Bold ABCDEFG Font: Adobe Jenson Bold Italic Typography 1: Typeface Classification Typeface Timeline Blackletter Humanist Old Style Transitional Modern Bauhaus Digital (aka Venetian) sans serif 1450 1460- 1716- 1700- 1780- 1920- 1980-present 1470 1728 1775 1880 1960 Typography 1: Typeface Classification Typeface Classification Humanist | Old Style | Transitional | Modern |Slab Serif (Egyptian) | Sans Serif The model for the first movable types was Blackletter (also know as Block, Gothic, Fraktur or Old English), a heavy, dark, at times almost illegible — to modern eyes — script that was common during the Middle Ages. from I Love Typography http://ilovetypography.com/2007/11/06/type-terminology-humanist-2/ Typography 1: : Typeface Classification Typeface Classification Humanist | Old Style | Transitional | Modern |Slab Serif (Egyptian) | Sans Serif Types based on blackletter were soon superseded by something a little easier Humanist (also refered to Venetian).. ABCDEFG ABCDEFG > abcdefg abcdefg Adobe Jenson Fette Fraktur Typography 1: : Typeface Classification Typeface Classification Humanist | Old Style | Transitional | Modern |Slab Serif (Egyptian) | Sans Serif The Humanist types (sometimes referred to as Venetian) appeared during the 1460s and 1470s, and were modelled not on the dark gothic scripts like textura, but on the lighter, more open forms of the Italian humanist writers. The Humanist types were at the same time the first roman types. Typography 1: : Typeface Classification Typeface Classification Humanist | Old Style | Transitional | Modern |Slab Serif (Egyptian) | Sans Serif Characteristics 1. -

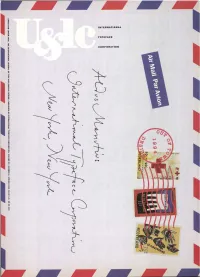

INTERNATIONAL TYPEFACE CORPORATION, to an Insightful 866 SECOND AVENUE, 18 Editorial Mix

INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION TYPEFACE UPPER AND LOWER CASE , THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF T YPE AND GRAPHI C DESIGN , PUBLI SHED BY I NTE RN ATIONAL TYPEFAC E CORPORATION . VO LUME 2 0 , NUMBER 4 , SPRING 1994 . $5 .00 U .S . $9 .90 AUD Adobe, Bitstream &AutologicTogether On One CD-ROM. C5tta 15000L Juniper, Wm Utopia, A d a, :Viabe Fort Collection. Birc , Btarkaok, On, Pcetita Nadel-ma, Poplar. Telma, Willow are tradmarks of Adobe System 1 *animated oh. • be oglitered nt certain Mrisdictions. Agfa, Boris and Cali Graphic ate registered te a Ten fonts non is a trademark of AGFA Elaision Miles in Womb* is a ma alkali of Alpha lanida is a registered trademark of Bigelow and Holmes. Charm. Ea ha Fowl Is. sent With the purchase of the Autologic APS- Stempel Schnei Ilk and Weiss are registimi trademarks afF mdi riot 11 atea hmthille TypeScriber CD from FontHaus, you can - Berthold Easkertille Rook, Berthold Bodoni. Berthold Coy, Bertha', d i i Book, Chottiana. Colas Larger. Fermata, Berthold Garauannt, Berthold Imago a nd Noire! end tradematts of Bern select 10 FREE FONTS from the over 130 outs Berthold Bodoni Old Face. AG Book Rounded, Imaleaa rd, forma* a. Comas. AG Old Face, Poppl Autologic typefaces available. Below is Post liedimiti, AG Sitoploal, Berthold Sr tapt sad Berthold IS albami Book art tr just a sampling of this range. Itt, .11, Armed is a trademark of Haas. ITC American T}pewmer ITi A, 31n. Garde at. Bantam, ITC Reogutat. Bmigmat Buick Cad Malt, HY Bis.5155a5, ITC Caslot '2114, (11 imam. -

Role Serif Display Pro

Morisawa Inc. Role Serif Display Pro Role Serif is part of the first stand-alone Latin typeface family released by Morisawa. Other genres in the family include Slab, Sans and Soft. Role Serif has the clearest image of seriousness or faithfulness among other styles. Text has the lowest contrast and the sturdy serifs for high legibility. The contrast gets higher for Display and Banner to help the look become more elegant. The letterforms are optimised for the target usage of each optical range. The letterforms of Text are consistent but morphs into the more decorative design for Display and Banner. The Display is in between Text and Banner and looks more graceful than Text but not too prominent to affect the versatility. Ban- ner is the most elegant design. The characteristic is more emphasised especially for the heavier weights where the widths narrow down. PUBLISHED: LANGUAGE: OPENTYPE FEATURES: 2019 Latin (98+) Proportional lining figures Proportional oldstyle figures FORMAT: SERIES & SCRIPTS: Fraction OpenType Role Serif Text Pro Case Sensitive form Role Serif Banner Pro Superscript/Subscript STYLES: Small Caps 14 Styles (7 weight with Italics) Caps to Small Caps Zero Slash Scientific Inferior DESIGNED BY: Localised Forms Matthew Carter Sakura Taruno Kunihiko Okano https://en.morisawa.co.jp | © 2019 Morisawa Inc. All rights reserved. Role Serif Display Pro STYLE SAMPLE Role Serif Display Pro Extralight Role Serif Display Pro Extralight Italic Role Serif Display Pro Light Role Serif Display Pro Light Italic Role Serif Display Pro Regular Role Serif Display Pro Italic Role Serif Display Pro Medium Role Serif Display Pro Medium Italic Role Serif Display Pro Bold Role Serif Display Pro Bold Italic Role Serif Display Pro Extrabold Role Serif Display Pro Extrabold Italic Role Serif Display Pro Heavy Role Serif Display Pro Heavy Italic https://en.morisawa.co.jp | © 2019 Morisawa Inc. -

Learners Guide

Published by National Vocational and Technical Training Commission Government of Pakistan Headquarter Plot 38, Kirthar Road, Sector H-9/4, Islamabad, Pakistan www.navttc.org Author Amreena Naz, Instructor, TEVTA Punjab) Responsible Director General Skills Standard and Curricula, National Vocational and Technical Training Commission National Deputy Head, TVET Reform Support Programme, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH Layout & design SAP Communications Photo Credits TVET Reform Support Programme URL links Responsibility for the content of external websites linked in this publication always lies with their respective publishers. TVET Reform Support Programme expressly dissociates itself from such content. This document has been produced with the technical assistance of the TVET Reform Support Programme, which is funded by the European Union, the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, the Federal Republic of Germany and the Royal Norwegian Embassy and has been commissioned by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). The Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH in close collaboration with the National Vocational and Technical Training Commission (NAVTTC) as well as provincial Technical Education and Vocational Training Authorities (TEVTAs), Punjab Vocational Training Council (PVTC), Qualification Awarding Bodies (QABs)s and private sector organizations. Document Version July, 2013 Islamabad, Pakistan Foreword The National Vocational & Technical Training Commission (NAVTTC) developed a National Skills Strategy (NSS) after extensive research and consultation with experts and stakeholders including policy makers and representatives from Industry, Academia and the Provincial Government departments dealing with technical and vocational training. The strategy aims at establishing a regime that facilitates competency-based and demand- driven training and assessment.