Cross Atlantic Flights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Operator Code Operator Name

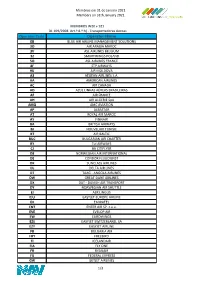

Membros em 31 de Janeiro 2021 Members on 31th January 2021 MEMBROS W20 + S21 DL 109/2008 Art.º 8.º h) - Transportadoras Aereas Operator Code Operator Name 0B BLUE AIR AIRLINE MANAGEMENT SOLUTIONS 3O AIR ARABIA MAROC 3V ASL AIRLINES BELGIUM 3Z SMARTWINGS POLAND 5O ASL AIRLINES FRANCE 8F STP AIRWAYS 9U AIR MOLDOVA A3 AEGEAN AIRLINES S.A. AA AMERICAN AIRLINES AC AIR CANADA AD AZUL LINHAS AÉREAS BRASILEIRAS AF AIR FRANCE AH AIR ALGERIE SpA AMQ AMC AVIATION AP ALBASTAR AT ROYAL AIR MAROC AY FINNAIR BA BRITISH AIRWAYS BJ NOUVELAIR TUNISIE BT AIR BALTIC BUC BULGARIAN AIR CHARTER BY Tui AIRWAYS CJ BA CITIFLYER D8 NORWEGIAN AIR INTERNATIONAL DE CONDOR FLUGDIENST DK SUNCLASS AIRLINES DL DELTA AIR LINES DT TAAG - ANGOLA AIRLINES DW GREAT DANE AIRLINES DX DAT - DANISH AIR TRANSPORT DY NORWEGIAN AIR SHUTTLE EI AER LINGUS EJU EASYJET EUROPE AIRLINE EK EMIRATES ENT ENTER AIR SP. z.o.o. EVE EVELOP AIR EW EUROWINGS EZS EASYJET SWITZERLAND, SA EZY EASYJET AIRLINE FB BULGARIA AIR FHY FREEBIRD FI ICELANDAIR FIA FLY ONE FR RYANAIR FX FEDERAL EXPRESS GW GETJET AIRLINES 1/3 Membros em 31 de Janeiro 2021 Members on 31th January 2021 HV TRANSAVIA AIRLINES I2 IBERIA EXPRESS IB IBERIA JAW JASMIN AIRWAYS JD BEIJING CAPITAL AIRLINES JJ TAM LINHAS AEREAS JNL JET NETHERLANDS BV KL KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES KM AIR MALTA LG LUXAIR LH LUFTHANSA LO LOT POLISH AIRLINES LS JET2.COM LX SWISS LY EL AL ISRAEL AIRLINES MYX SMARTLYNX AIRLINES ESTONIA NI PGA PORTUGALIA AIRLINES NO NEOS NT BINTER CANARIAS NVR AVION EXPRESS OBS ORBEST OE LAUDAMOTION GMBH OG FLYPLAY OR TUI AIRLINES -

Austria 2020 440 Austrian Airlines AG 424300 19210 UIA-VB 3289 30323

Annex I EN Changes to National allocation table for the year 2020 pursuant to the Agreement between the European Union and the Swiss Confederation on the linking of their greenhouse emissions trading systems, and to the Commission Delegated Decision C(2020) 3107 Note: The values for 2020 are total. They include the initial allocation for the flights between EEA Aerodromes and the additional allocation for the flights to and within Switzerland. These values need to be inserted as updates in the National Aviation Allocation Tables XML file. Member State: Austria ETSID Operator name 2020 440 Austrian Airlines AG 424300 19210 UIA-VB 3289 30323 International Jet Management GmbH 157 33061 AVCON JET AG 83 28567 Tupack Verpackungen Gesellschaft m.b.H. 17 25989 The Flying Bulls 16 45083 easyJet Europe Airline GmbH 1823642 Member State: Belgium ETSID Operator name 2020 908 BRUSSELS AIRLINES 285422 27011 ASL Airlines Belgium 110688 2344 SAUDI ARABIAN AIRLINES CORPORATION 3031 32432 EgyptAir 315 29427 Flying Service 271 13457 EXCLU Flying Partners CVBA 81 36269 EXCLU VF International SAGL 22 28582 EXCLU Inter-Wetail c/o Jet Aviation Business Jets AG 14 Member State: Bulgaria ETSID Operator name 2020 29056 Bulgaria Air 81265 28445 BH AIR 41204 Member State: Croatia ETSID Operator name 2020 12495 Croatia Airlines hrvatska zrakoplovna tvrtka d.d. 88551 Member State: Cyprus ETSID Operator name 2020 7132 Joannou & Paraskevaides (Aviation) Limited 30 Member State: Czechia ETSID Operator name 2020 859 České aerolinie a.s. 256608 24903 Smartwings, a.s. 119819 -

Economic Development of Ultra Small Peripheral Regions of West Europe (Case of Aland and Faroe Islands)

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Efimova, Elena; Kuznetsova, Natalia Conference Paper Economic development of ultra small peripheral regions of West Europe (Case of Aland and Faroe islands) 54th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Regional development & globalisation: Best practices", 26-29 August 2014, St. Petersburg, Russia Provided in Cooperation with: European Regional Science Association (ERSA) Suggested Citation: Efimova, Elena; Kuznetsova, Natalia (2014) : Economic development of ultra small peripheral regions of West Europe (Case of Aland and Faroe islands), 54th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Regional development & globalisation: Best practices", 26-29 August 2014, St. Petersburg, Russia, European Regional Science Association (ERSA), Louvain-la-Neuve This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/124527 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Die Folgende Liste Zeigt Alle Fluggesellschaften, Die Über Den Flugvergleich Von Verivox Buchbar Sein Können

Die folgende Liste zeigt alle Fluggesellschaften, die über den Flugvergleich von Verivox buchbar sein können. Aufgrund von laufenden Updates einzelner Tarife, technischen Problemen oder eingeschränkten Verfügbarkeiten kann es vorkommen, dass einzelne Airlines oder Tarife nicht berechnet oder angezeigt werden können. 1 Adria Airways 2 Aegean Airlines 3 Aer Arann 4 Aer Lingus 5 Aeroflot 6 Aerolan 7 Aerolíneas Argentinas 8 Aeroméxico 9 Air Algérie 10 Air Astana 11 Air Austral 12 Air Baltic 13 Air Berlin 14 Air Botswana 15 Air Canada 16 Air Caraibes 17 Air China 18 Air Corsica 19 Air Dolomiti 20 Air Europa 21 Air France 22 Air Guinee Express 23 Air India 24 Air Jamaica 25 Air Madagascar 26 Air Malta 27 Air Mauritius 28 Air Moldova 29 Air Namibia 30 Air New Zealand 31 Air One 32 Air Serbia 33 Air Transat 34 Air Asia 35 Alaska Airlines 36 Alitalia 37 All Nippon Airways 38 American Airlines 39 Arkefly 40 Arkia Israel Airlines 41 Asiana Airlines 42 Atlasglobal 43 Austrian Airlines 44 Avianca 45 B&H Airlines 46 Bahamasair 47 Bangkok Airways 48 Belair Airlines 49 Belavia Belarusian Airlines 50 Binter Canarias 51 Blue1 52 British Airways 53 British Midland International 54 Brussels Airlines 55 Bulgaria Air 56 Caribbean Airlines 57 Carpatair 58 Cathay Pacific 59 China Airlines 60 China Eastern 61 China Southern Airlines 62 Cimber Sterling 63 Condor 64 Continental Airlines 65 Corsair International 66 Croatia Airlines 67 Cubana de Aviacion 68 Cyprus Airways 69 Czech Airlines 70 Darwin Airline 71 Delta Airlines 72 Dragonair 73 EasyJet 74 EgyptAir 75 -

Continuing Airworthiness Organisations

Continuing Airworthiness Organisations Status date: 7. January 2021 Parameter Settings Include CAMO : Yes Include CAO : Yes Include 145 : Yes Include MF : Yes Include other approved addresses: Yes Include Ratings and Limitations: Yes Sorting order: Name of organisation page 1 of 106 Table of contents 1. CAMO 1.1 Air Alsie A/S 1.2 Air Greenland A/S 1.3 Air Service Vamdrup (FLYSYN.DK) ApS 1.4 Atlantic Airways, Faroe Islands, P/F 1.5 Bel Air Aviation A/S 1.6 Benair A/S 1.7 Blackbird Air A/S 1.8 Blue West Helicopters Greenland ApS 1.9 Bornfly ApS 1.10 Copenhagen AirTaxi A/S 1.11 C9H ApS 1.12 Dansk Ballonunion 1.13 Dansk Svæveflyver Union 1.14 DAO Aviation A/S 1.15 DAT A/S 1.16 ExecuJet Europe A/S 1.17 Falck DRF Luftambulance A/S 1.18 FlexFlight ApS 1.19 General Aviation Service ApS 1.20 Great Dane Airlines A/S 1.21 Greenlandcopter A/S 1.22 Greybird Maintenance ApS 1.23 Helico ApS 1.24 Jettime A/S 1.25 Kalundborg Aviation v/ Thorkild Kristensen 1.26 KN Helicopters A/S 1.27 Newcopter ApS 1.28 NHV A/S 1.29 Nordic Aviation Capital A/S 1.30 North Flying A/S 1.31 Skyways Technics A/S 1.32 Star Air A/S 1.33 Starling Air 1.34 Steff Aviation ApS 1.35 Sun-Air of Scandinavia A/S 1.36 Sunclass Airlines ApS 1.37 Sunclass Airways A/S 1.38 Uni-Fly A/S 2. -

Foreign ICAO 3LD Additions and Modifications (Excluding U.S.)

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION N JO 7340.660 NOTICE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION Air Traffic Organization Policy Effective Date: August 13, 2021 Cancellation Date: August 13, 2022 SUBJ: Foreign ICAO 3LD Additions and Modifications (excluding U.S.) 1. Purpose of This Notice. This notice modifies FAA Order JO 7340.2, Contractions, Chapter 3, Sections 1, 2, and 3, ICAO Aircraft Company Three-Letter Identifier and/or Telephony Designator. This notice reflects recent changes initiated by countries other than the United States (U.S.) including new ICAO three letter designators (3LDs), deletions of defunct ICAO 3LDs, and modifications to ICAO 3LDs, associated telephonies, and companies/agencies. This Notice supplements FAA Order JO 7340.2 until the additions and modifications are incorporated into the Order. This Notice does not replace or substitute for GENOTs issued by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Air Traffic Organization (ATO) for ICAO 3LDs assigned and authorized for U.S. aircraft operators. 2. Audience. This notice applies to the following Air Traffic Organization (ATO) service units: Air Traffic Services, and System Operations Services; ATO Safety and Technical Training; and all associated air traffic control facilities. This notice is informational in nature and does not require documentation as supplemental training in FAA Form 3120-1, Training and Proficiency Record. 3. Where Can I Find This Notice? This notice is available on the MyFAA employee website at https://employees.faa.gov/tools_resources/orders_notices/ and on the air traffic publications website at http://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/. 4. Source Document. The source document for the ICAO 3LD additions and modifications contained in this notice is ICAO Document 8585, Designators for Aircraft Operating Agencies, Aeronautical Authorities, and Services. -

List of EU Air Carriers Holding an Active Operating Licence

Active Licenses Operating licences granted Member State: Austria Decision Name of air carrier Address of air carrier Permitted to carry Category (1) effective since ABC Bedarfsflug GmbH 6020 Innsbruck - Fürstenweg 176, Tyrolean Center passengers, cargo, mail B 16/04/2003 AFS Alpine Flightservice GmbH Wallenmahd 23, 6850 Dornbirn passengers, cargo, mail B 20/08/2015 Air Independence GmbH 5020 Salzburg, Airport, Innsbrucker Bundesstraße 95 passengers, cargo, mail A 22/01/2009 Airlink Luftverkehrsgesellschaft m.b.H. 5035 Salzburg-Flughafen - Innsbrucker Bundesstraße 95 passengers, cargo, mail A 31/03/2005 Alpenflug Gesellschaft m.b.H.& Co.KG. 5700 Zell am See passengers, cargo, mail B 14/08/2008 Altenrhein Luftfahrt GmbH Office Park 3, Top 312, 1300 Wien-Flughafen passengers, cargo, mail A 24/03/2011 Amira Air GmbH Wipplingerstraße 35/5. OG, 1010 Wien passengers, cargo, mail A 12/09/2019 Anisec Luftfahrt GmbH Office Park 1, Top B04, 1300 Wien Flughafen passengers, cargo, mail A 09/07/2018 ARA Flugrettung gemeinnützige GmbH 9020 Klagenfurt - Grete-Bittner-Straße 9 passengers, cargo, mail A 03/11/2005 ART Aviation Flugbetriebs GmbH Porzellangasse 7/Top 2, 1090 Wien passengers, cargo, mail A 14/11/2012 Austrian Airlines AG 1300 Wien-Flughafen - Office Park 2 passengers, cargo, mail A 10/09/2007 Disclaimer: The table reflects the data available in ACOL-database on 16/10/2020. The data is provided by the Member States. The Commission does not guarantee the accuracy or the completeness of the data included in this document nor does it accept responsibility for any use made thereof. 1 Active Licenses Decision Name of air carrier Address of air carrier Permitted to carry Category (1) effective since 5020 Salzburg-Flughafen - Innsbrucker Bundesstraße AVAG AIR GmbH für Luftfahrt passengers, cargo, mail B 02/11/2006 111 Avcon Jet AG Wohllebengasse 12-14, 1040 Wien passengers, cargo, mail A 03/04/2008 B.A.C.H. -

Sustainable Jet Fuel for Aviation - Update 2019

Sustainable Jet Fuel for Aviation Nordic perspectives on the use of advanced sustainable jet fuel for aviation - Update 2019 NORDIC ENERGY RESEARCH JANUARY 2020 Nordic Energy Research January 2020 www.niras.dk This report has been prepared by: NIRAS A/S Erik C. Wormslev Mathilde K. Broberg QA by: Christian Eriksen (NIRAS) Martin Porsgaard (NISA) 2 Nordic Energy Research January 2020 www.niras.dk Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Executive Summary 5 1.2 Process and structure 6 1.3 Studies on sustainable aviation fuel 6 2 Global Status of Sustainable Aviation Fuel 8 2.1 Approved technology pathways 8 Fischer-Tropsch Synthetic Paraffinic Kerosene FT-SPK/A 8 Alcohol-to-Jet Synthetic Paraffinic Kerosene (AtJ-SPK) 8 2.2 Emerging technologies 8 2.3 Nordic stakeholder initiatives 9 Multi-stakeholder initiatives 12 2.3.1.1 NISA, Nordic Initiative for Sustainable Aviation 12 2.3.1.2 Conference on sustainable aviation 12 2.3.1.3 The Nordic Network for Electric Aviation (NEA) 12 2.3.1.4 EUDP (a Danish Energy Technology Development and Demonstration Program), Power2Met 12 2.3.1.5 Electro fuel from a bio-trickling filter (eFuel) 12 2.3.1.6 Innovation Fund Denmark, SYNFUEL project 13 2.3.1.7 EUDP Electro fuel from a bio-trickling filter (eFuel) 13 2.3.1.8 Green hydrogen and electrofuels in Sweden 13 2.3.1.9 Future Liquid Aviation Biofuels Based on Ethers for Gas Turbine Engines (FLABBERGAST) 13 2.3.1.10 Partnership Fossilfria Flygtransporter 13 2.3.1.11 Flying on forest residues in Småland, Sweden 14 2.3.1.12 Validation and demonstration of forest based bio jet fuel 14 2.3.1.13 The Roundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials (RSB) 14 3 Production capacities of SAF in the Nordic countries and price estimates. -

G:\JPH Section\ADU CODELIST\Codelist.Snp

Codelist Economic Regulation Group Aircraft By Name By CAA Code Airline By Name By CAA Code By Prefix Airport By Name By IATA Code By ICAO Code By CAA Code Codelist - Aircraft by Name Civil Aviation Authority Aircraft Name CAA code End Month AEROSPACELINES B377SUPER GUPPY 658 AEROSPATIALE (NORD)262 64 AEROSPATIALE AS322 SUPER PUMA (NTH SEA) 977 AEROSPATIALE AS332 SUPER PUMA (L1/L2) 976 AEROSPATIALE AS355 ECUREUIL 2 956 AEROSPATIALE CARAVELLE 10B/10R 388 AEROSPATIALE CARAVELLE 12 385 AEROSPATIALE CARAVELLE 6/6R 387 AEROSPATIALE CORVETTE 93 AEROSPATIALE SA315 LAMA 951 AEROSPATIALE SA318 ALOUETTE 908 AEROSPATIALE SA330 PUMA 973 AEROSPATIALE SA341 GAZELLE 943 AEROSPATIALE SA350 ECUREUIL 941 AEROSPATIALE SA365 DAUPHIN 975 AEROSPATIALE SA365 DAUPHIN/AMB 980 AGUSTA A109A / 109E 970 AGUSTA A139 971 AIRBUS A300 ( ALL FREIGHTER ) 684 AIRBUS A300-600 803 AIRBUS A300B1/B2 773 AIRBUS A300B4-100/200 683 AIRBUS A310-202 796 AIRBUS A310-300 775 AIRBUS A318 800 AIRBUS A319 804 AIRBUS A319 CJ (EXEC) 811 AIRBUS A320-100/200 805 AIRBUS A321 732 AIRBUS A330-200 801 AIRBUS A330-300 806 AIRBUS A340-200 808 AIRBUS A340-300 807 AIRBUS A340-500 809 AIRBUS A340-600 810 AIRBUS A380-800 812 AIRBUS A380-800F 813 AIRBUS HELICOPTERS EC175 969 AIRSHIP INDUSTRIES SKYSHIP 500 710 AIRSHIP INDUSTRIES SKYSHIP 600 711 ANTONOV 148/158 822 ANTONOV AN-12 347 ANTONOV AN-124 820 ANTONOV AN-225 MRIYA 821 ANTONOV AN-24 63 ANTONOV AN26B/32 345 ANTONOV AN72 / 74 647 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH ARGOSY 349 ATR42-300 200 ATR42-500 201 ATR72 200/500/600 726 AUSTER MAJOR 10 AVIONS MUDRY CAP 10B 601 AVROLINER RJ100/115 212 AVROLINER RJ70 210 AVROLINER RJ85/QT 211 AW189 983 BAE (HS) 748 55 BAE 125 ( HS 125 ) 75 BAE 146-100 577 BAE 146-200/QT 578 BAE 146-300 727 BAE ATP 56 BAE JETSTREAM 31/32 340 BAE JETSTREAM 41 580 BAE NIMROD MR. -

Police Marina Sav Ant Nt Uia Naval Air Hohwreiler, Kenneth P

t,' ■ \ • w MONDAY, JUNE^B, 19B« >AOI >t)US1CEll » ATtrafs Daily Net Press Rss The Weather - lianrl;pist(r ISnrnitto V^ralb Far tba W eek Badad Faraaaat af V. 8. Waatbar BmeeB ■ ' • ' ' ..I_________ _ Same IS. IMO C l^ . eaal taiaigbt. LaW la aOi Linda A. Giacomlni, Joan A. Broa. haa ever houaed workem Ma. Fair Wadaraday asoialag, 127 Piano Pupil§ Schaibenpflug, Helen 1. Jette. Girls to Work there. 12,065 waim la aftamaoa, sliawrars, tSee- A bou t Tow n Maureen S. Kerr. Gail J. CoUvac- Grange Notes AccordiM to the local.odTice Sr drniteniM at lOgiM. Higti le aaM On Farms Here the State Employment Service, a Maaabar ad tbs AaSIt se*. Heard in Recital chio, David W. Bell. Donna L, Me* number of other tobacco growera Baraae ad Onmlattam Mtmehester-^A City of FlU of* Chants Mtetiw l**t J<tlm D. MUvan. aaln.'Jeanr Ann Vincent. Betty M. in the area will, in the next fCw Vlncerft. Donna U Chandler. Ed Wa'pping Orange, Nd. 30, will ton oC Mr. -Md Mrs. lUymond i . An appreciative audience of ' Some. M ^rla from Tanipa aAd .waeka. be provided With girla for HALE'S mund S. Tiaglio. Victor I. Zubrow, meet Tueaday at 8 o'clock. It pill Plant City, Fla., arrived in Mah- m m m m . B >n*d St., U now on Iparanta and friendi attended the farm work. Theae*workera will be (CSaasUlai AdvaHWag aa faga iU) « £ to H U » a nfter eompMUiis Janice C, Smith, Karen E. Wal be Mualc Night .with Evelyn cheater yeaUMay for aummer to I houaed in rwmpe on the farma. -

Pilot/Controller Collaboration Initiatives: Enhancing Safety and Efficiency

PILOT/ CONTROLLER COLLABORATION INITIATIVES: Enhancing Safety and Efficiency First Edition • June 2003 005503.qxd Disclaimer Unless otherwise specifically stated, the information contained within this report is made available by the Global Aviation Information Network (GAIN) for information purposes only. Neither GAIN nor any of its participants or entities thereof, assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the report’s accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product, or process disclosed. References within this report to any specific product, process, service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, individual, or otherwise, does not constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favouring by GAIN or any entities thereof. Any views, analysis, and opinions expressed are the sole responsibility of their authors. In all cases, any initiatives developed should be consistent with prevailing agreements, regulations, and instructions set out in appropriate controlling documentation. Pilot/Controller Collaboration Initiatives: Enhancing Safety and Efficiency Prepared by: GAIN Working Group E, Flight Ops/ATC Ops Safety Information Sharing First Edition · June 2003 This report is available online at www.gainweb.org THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Table of Contents Page Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................................iii Executive Summary .....................................................................................................................vii -

Continuing Airworthiness Organisations

Continuing Airworthiness Organisations Status date: 1. October 2021 Parameter Settings Include CAMO : Yes Include CAO : Yes Include 145 : Yes Include MF : Yes Include other approved addresses: Yes Include Ratings and Limitations: Yes Sorting order: Approval No page 1 of 98 Table of contents 1. CAMO 1.1 DK.CAMO.0003 1.2 DK.CAMO.0008 1.3 DK.CAMO.0009 1.4 DK.CAMO.0012 1.5 DK.CAMO.0030 1.6 DK.CAMO.0031 1.7 DK.CAMO.0033 1.8 DK.CAMO.0039 1.9 DK.CAMO.0041 1.10 DK.CAMO.0045 1.11 DK.CAMO.0051 1.12 DK.CAMO.0058 1.13 DK.CAMO.0081 1.14 DK.CAMO.0082 1.15 DK.CAMO.0083 1.16 DK.CAMO.0084 1.17 DK.CAMO.0085 1.18 DK.CAMO.0087 1.19 DK.CAMO.1001 1.20 DK.CAMO.1007 1.21 DK.CAMO.1012 1.22 DK.CAMO.1015 1.23 DK.CAMO.1016 1.24 DK.MG.0007 1.25 DK.MG.0021 1.26 DK.MG.0043 1.27 DK.MG.0052 1.28 DK.MG.0068 1.29 DK.MG.0070 1.30 DK.MG.0073 1.31 DK.MG.0076 1.32 DK.MG.0077 1.33 DK.MG.0079 1.34 DK.MG.1008 2. CAO 2.1 DK.CAO.0001 2.2 DK.CAO.0002 2.3 DK.CAO.0003 2.4 DK.CAO.0004 2.5 DK.CAO.0005 3. Part-145 Maintenance Organisations 3.1 DK.145.0002 3.2 DK.145.0007 3.3 DK.145.0009 3.4 DK.145.0015 3.5 DK.145.0018 3.6 DK.145.0019 3.7 DK.145.0020 3.8 DK.145.0022 3.9 DK.145.0025 3.10 DK.145.0027 3.11 DK.145.0033 3.12 DK.145.0039 3.13 DK.145.0050 3.14 DK.145.0055 3.15 DK.145.0060 3.16 DK.145.0072 page 2 of 98 3.17 DK.145.0075 3.18 DK.145.0076 3.19 DK.145.0079 3.20 DK.145.0081 3.21 DK.145.0083 3.22 DK.145.0087 3.23 DK.145.0092 3.24 DK.145.0094 3.25 DK.145.0097 3.26 DK.145.0098 3.27 DK.145.0099 3.28 DK.145.0102 3.29 DK.145.0103 3.30 DK.145.0104 3.31 DK.145.0105 3.32 DK.145.0107 3.33 DK.145.0108 3.34 DK.145.0109 3.35 DK.145.0110 3.36 DK.145.0112 3.37 DK.145.0113 3.38 DK.145.0114 3.39 DK.145.0115 page 3 of 98 1.