Sorani Kurdish— a Reference Grammar with Selected Readings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Kurmanji Kurdish As

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Kurmanji Kurdish as Spoken in Turkey 1. Special handling of dialects Kurmanji Kurdish is a major branch of modern Kurdish, which belongs to the Iranian group of languages. Kurdish is largely a spoken language with a limited but growing body of modern literature. There are many dialectal varieties of Kurdish spread over a wide area of Turkey, Iraq, Syria, Iran, Armenia and Azerbaijan. There are, in addition, different classifications of Kurdish languages and Kurdish peoples that align dialectal choice with tribal affinity. Linguistic and Kurdish scholars usually describe modern Kurdish as having two closely related major branches: Kurmanji (the northern branch) and Sorani (the southern branch). They are not mutually intelligible (see Thackston (2006) p. vii). The Kurdish Institute summarizes the situation as follows: “Kurdish has two regional standards, namely Kurmanji in Turkey, and Sorani farther east and south. Roughly half of Kurdish speakers live in Turkey.” (see http://www.institutkurde.org/en/ and also http://www.blueglobetranslations.com/about- kurdish-kurmanji-language.html). Within the larger region there are two other languages often associated with ethnic Kurds. These are Dimili (also known as Zazaki) and Gorani. Although sometimes classified as sub-dialects of Kurdish (e.g., Kurdish Language - Britannica Online Encyclopedia), these languages belong to a different group of Iranian languages (see for example, http://kurds_history.enacademic.com/346/Kurmanji). Although Kurmanji Kurdish is spoken across a range of countries, it has the advantage of being spoken by around 60-80% of Kurds and is considered a regional standard. The majority of Kurmanji speakers live in Turkey, making it the ideal country for collection of audio data (see for example, http://linguakurd.blogfa.com/post-106.aspx). -

Deixis and Reference Tracing in Tsova-Tush (PDF)

DEIXIS AND REFERENCE TRACKING IN TSOVA-TUSH A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS MAY 2020 by Bryn Hauk Dissertation committee: Andrea Berez-Kroeker, Chairperson Alice C. Harris Bradley McDonnell James N. Collins Ashley Maynard Acknowledgments I should not have been able to finish this dissertation. In the course of my graduate studies, enough obstacles have sprung up in my path that the odds would have predicted something other than a successful completion of my degree. The fact that I made it to this point is a testament to thekind, supportive, wise, and generous people who have picked me up and dusted me off after every pothole. Forgive me: these thank-yous are going to get very sappy. First and foremost, I would like to thank my Tsova-Tush host family—Rezo Orbetishvili, Nisa Baxtarishvili, and of course Tamar and Lasha—for letting me join your family every summer forthe past four years. Your time, your patience, your expertise, your hospitality, your sense of humor, your lovingly prepared meals and generously poured wine—these were the building blocks that supported all of my research whims. My sincerest gratitude also goes to Dantes Echishvili, Revaz Shankishvili, and to all my hosts and friends in Zemo Alvani. It is possible to translate ‘thank you’ as მადელ შუნ, but you have taught me that gratitude is better expressed with actions than with set phrases, sofor now I will just say, ღაზიშ ხილჰათ, ბედნიერ ხილჰათ, მარშმაკიშ ხილჰათ.. -

NACIL. Sorani Pptx

Identity Avoidance in Morphology; Evidence from Polyfunctional Clitics of Sorani Kurdish Sahar Taghipour University of Kentucky April 2017 In this study ´ Kurdish and its dialects In this study ´ Kurdish and Its Dialects ´ Polyfunctional Clitics in Sorani Kurdish In this study ´ Kurdish and its dialects ´ Polyfunctional Clitics in Sorani Kurdish ´ Morphological Haplology In this study ´ Kurdish and its dialects ´ What are the polyfunctional clitics in Sorani Kurdish ´ Morphological Haplology ´ Constraint-based Morphology with basic concepts from Optimality Theory (Prince and Smolensky: 1993 ) Kurdish and its dialects ´ Iranian languages are divided into two major branches: Western and Eastern Southwestern (Persian) and Northwestern (Kurdish) ´ Kurdish “Is a cover term for a cluster of northwest Iranian languages and dialects spoken by between 20 and 30 million speakers in a contiguous area of West Iran, North Iraq, eastern Turkey and eastern Syria” (Haig and Opengin: 2015) Northern, Central, and Southern(Windfuhr (2009) “In terms of numbers of speakers and degree of standardization, the two most important Kurdish dialects are Sorani (Central Kurdish) and Kurmanji (Northern Kurdish)” (Haig and Matras: 2002) Where Kurdish is spoken? ´ Northern Kurdish (Kurmanji) They’re mainly in Turkey, Iraq, Syria, and Western Azarbayjan in Iran ´ Central Kurdish (Sorani or Mukri) Some parts in Iraq and Iran (Northwestern, Northeastern, in particular ) ´ Southern Kermanshah and Ilam Province (West and Southwestern part of Iran) Sorani and Its Dialects In this study, I am going to talk in particular about Sorani Kurdish. Its dialects are: Mukriyani Ardalani Garmiani Hawlari Babani Jafi Sorani and Its Dialects In this study, I am going to talk in particular about Sorani Kurdish. -

Book Reviews Mélanges D'ethnographie Et De

Iran and the Caucasus 22 (2018) 419-422 Book Reviews Mélanges d’ethnographie et de dialectologie Irano-Aryennes à la mémoire de Charles-Martin Kieffer (Studia Iranica, Cahier 61), edited by Matteo De Chiara, Adriano V. Rossi, and Daniel Septfonds, Leuven: “Peeters”, 2018.— 413 pp. + map. The volume is dedicated to the memory of Charles-Martin Kieffer, the prominent French linguist and ethnographer on matters Afghanica. Kief- fer’s fundamental contribution to the Atlas Linguistique de l’Afghanistan, the description of two critically endangered Iranian languages (Ōrmuṛi of Baraki-Barak and Parāči), as well as data on language taboos in Afghan countryside, remain crucial for the research on Afghan ethnography and socio-linguistic situation in Afghanistan. The range of the topics of sixteen articles collected in Kieffer’s homage is wide enough to include contributions on Ossetic funeral rites and Balo- chi war-ballads, influence of Pashto on Dardic languages of Afghanistan and prefixes in Ormuri, etc. L. Arys in “Les Rites Funéraires Ossètes”, highlights the archaic charac- ter of the funerary customs among the Iranian-speaking Ossetes in the Caucasus and shows how this tradition is still important for a contempo- rary Ossete family. S. Badalkhan (“A Balochi Ballad on the Brāhō-Jadgāl Wars and the formation of Brāhōī Tribes”) presents a piece from the rich Balochi oral tradition, a 17th century ballad recounting the tribal confrontation and clashes between multilingual (Balochi, Jadgali, Brahoi) units in Kalat and Khuzdar districts, which led to the formation of Brahoi tribes based on heterogenous elements. H. Borjian’s article, “The Dialect of Khur”, is a skectch of the grammar of a largely understudied dialect of Biabanak district at the southern bor- der of Dasht-e Kavir desert in Iran. -

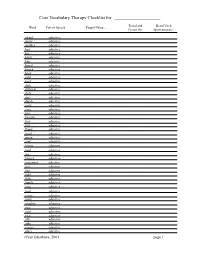

250 Word List

Core Vocabulary Therapy Checklist for ____________________ Tested and Heard Used Word Part of Speech Taught Using ... Passed On: Spontaneously: afraid adjective angry adjective another adjective bad adjective big adjective black adjective blue adjective bored adjective brown adjective busy adjective cold adjective cool adjective dark adjective different adjective dirty adjective dry adjective dumb adjective early adjective easy adjective fast adjective favorite adjective first adjective full adjective funny adjective good adjective green adjective grey adjective happy adjective hard adjective hot adjective hungry adjective important adjective last adjective late adjective light adjective little adjective lonely adjective long adjective mad adjective many adjective more adjective naughty adjective new adjective next adjective nice adjective old adjective only adjective orange adjective other adjective ©VanTatenhove, 2001 page 1 Core Vocabulary Therapy Checklist for ____________________ Word Part of Speech Taught Using ... Tested and Heard Used Passed On: Spontaneously: pink adjective purple adjective real adjective red adjective right adjective sad adjective same adjective sick adjective silly adjective sure adjective thirsty adjective tired adjective wet adjective white adjective wrong adjective yellow adjective adjective adjective adjective again adverb all right adverb almost adverb already adverb always adverb away adverb backwards adverb forward adverb here adverb indoors adverb just adverb maybe adverb much adverb never adverb not -

Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive Dorothy Disterheft University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected]

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Linguistics, Program of 1981 Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive Dorothy Disterheft University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ling_facpub Part of the Linguistics Commons Publication Info Published in Folia Linguistica Historica, Volume 2, Issue 1, 1981, pages 3-34. Disterheft, D. (1981). Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive. Folia Linguistica Historica, 2(1), 3-34. DOI: 10.1515/ flih.1981.2.1.3 © 1981 Societas Linguistica Europaea. This Article is brought to you by the Linguistics, Program of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Foli.lAfl//ui.tfcoFolia Linguistica HfltorlcGHistorica II/III/l 'P'P.pp. 8-U3—Z4 © 800£etruSocietae lAngu,.ticaLinguistica Etlropaea.Evropaea, 1981lt)8l REMARKSBEMARKS ONON THETHE HISTORYHISTOKY OFOF THETHE INDO-EUROPEANINDO-EUROPEAN INFINITIVEINFINITIVE i DOROTHYDOROTHY DISTERHEFTDISTERHEFT I 1.1. INTRODUCTIONINTRODUCTION WithWith thethe exceptfonexception ofof Indo-IranianIndo-Iranian (Ur)(Hr) andand CelticCeltic allall historicalhistorical Indo-EuropeanIndo-European (IE)(IE) subgroupssubgroups havehave a morphologicalIymorphologically distinctdistinct II infinitive.Infinitive. However,However, nono singlesingle proto-formproto-form cancan bebe reconstructedreconstructed -

A Study of European, Persian, and Arabic Loans in Standard Sorani

A Study of European, Persian, and Arabic Loans in Standard Sorani Jafar Hasanpoor Doctoral dissertation for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Iranian languages presented at Uppsala University 1999. ABSTRACT Hasanpoor, J. 1999: A Study of European, Persian and Arabic Loans in Standard Sorani. Reports on Asian and African Studies (RAAS) 1. XX pp. Uppsala. ISBN 91-506-1353-7. This dissertation examines processes of lexical borrowing in the Sorani standard of the Kurdish language, spoken in Iraq, Iran, and the Kurdish diaspora. Borrowing, a form of language contact, occurs on all levels of language structure. In the pre-standard literary Kurdish (Kirmanci and Sorani) which emerged in the pre-modern period, borrowing from Arabic and Persian was a means of developing a distinct literary and linguistic tradition. By contrast, in standard Sorani and Kirmanci, borrowing from the state languages, Arabic, Persian, and Turkish, is treated as a form of domination, a threat to the language, character, culture, and national distinctness of the Kurdish nation. The response to borrowing is purification through coinage, internal borrowing, and other means of extending the lexical resources of the language. As a subordinate language, Sorani is subjected to varying degrees of linguistic repression, and this has not allowed it to develop freely. Since Sorani speakers have been educated only in Persian (Iran), or predominantly in Arabic, European loans in Sorani are generally indirect borrowings from Persian and Arabic (Iraq). These loans constitute a major source for lexical modernisation. The study provides wordlists of European loanwords used by Hêmin and other codifiers of Sorani. -

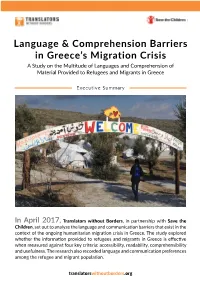

Language & Comprehension Barriers in Greece's Migration Crisis

Language & Comprehension Barriers in Greece’s Migration Crisis A Study on the Multitude of Languages and Comprehension of Material Provided to Refugees and Migrants in Greece Executive Summary In April 2017, Translators without Borders, in partnership with Save the Children, set out to analyze the language and communication barriers that exist in the context of the ongoing humanitarian migration crisis in Greece. The study explored whether the information provided to refugees and migrants in Greece is effective when measured against four key criteria: accessibility, readability, comprehensibility and usefulness. The research also recorded language and communication preferences among the refugee and migrant population. translatorswithoutborders.org The research combined quantitative and qualitative methods and was carried out in April 2017, at 11 sites in Greece. The findings are based on 202 surveys with refugees and migrants, and 22 interviews with humanitarian aid workers. The surveys and interviews were conducted in Arabic, Kurmanji, Sorani, Farsi, Dari, Greek and English. The findings, while not exhaustive, do pinpoint a number of important language and communication issues that are of importance for the management of the humanitarian situation as a whole. Key findings The language in which information is provided is of critical importance. The vast majority of respondents would prefer to receive information in their mother tongue; where that is not possible, English is not seen as an adequate alternative in most cases. Eighty-eight percent of participants preferred to receive information in their mother tongue. Speakers of “minority” languages such as Sorani, Baluchi and Lingala do not receive sufficient information in Greece, as there are not enough interpreters or cultural mediators for these languages. -

Navajo Verb Stem Position and the Bipartite Structure of the Navajo

678 REMARKSANDREPLIES NavajoVerb Stem Positionand the BipartiteStructure of the NavajoConjunct Sector Ken Hale TheNavajo verb stem appears at the rightmost edge of the verb word. Innumerouscases it forms a lexicalconstituent with a preverb,occur- ringat theleftmost edge of thesurface verb word, much in themanner ofDutchand German verb-particle arrangements in verb-secondfinite clauses.In Navajothe initial and finalpositions are separated by eight morphemeorder ‘ ‘slots’’ recognizedin the Athabaskan literature (and describedin detail for Navajo in Young and Morgan 1987). A phono- logicalsolution to this and a numberof otherdeep-surface disparities isexploredhere, based on theinsights of earlierworks on theNavajo verb,including Speas 1984, 1990, McDonough 1996, 2000, and Rice 1989, 2000. Keywords: verbmorphology, morphosyntactic disparity, spell-out, Navajo,Athabaskan 1Verb Stem Position TheNavajo verb stem forms asinglelexical constituent with the prefixal, particle-like category called preverb inthe Athabaskan linguistic literature (see Rice2000). However, like particle- verbcombinations in Dutchand German verb-second clauses, the parts of thisconstituent in the Navajocounterpart are separated in the surface forms ofverbal projections in syntax. In the Navajoversion of thisarrangement, the preverb occupies the leftmost position in the verb word, andthe verb stem occupies the rightmost position. TheNavajo verb in (1) canbe used to illustrate the phenomenon. The verb is segmented intoits various parts in (2), and the components are identified in slightly greater detail in (3). (1) Sila´o t’o´o´’go´o´ ch’´õ shidinõ´daøzh.(Young and Morgan 1987:283) ‘Thepoliceman jerked me outdoors (to get me out of afight).’ (2) ch’´õ sh d n-´ daøzh PreverbObject Qualifier Mode/ SubjVoice V (stem) Iwishto dedicate thisarticle totheNavajo Language Academy, asmall groupof linguists and teachers devotedto Navajolanguage research andeducation. -

Unity and Diversity in Grammaticalization Scenarios

Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios Edited by Walter Bisang Andrej Malchukov language Studies in Diversity Linguistics 16 science press Studies in Diversity Linguistics Chief Editor: Martin Haspelmath In this series: 1. Handschuh, Corinna. A typology of marked-S languages. 2. Rießler, Michael. Adjective attribution. 3. Klamer, Marian (ed.). The Alor-Pantar languages: History and typology. 4. Berghäll, Liisa. A grammar of Mauwake (Papua New Guinea). 5. Wilbur, Joshua. A grammar of Pite Saami. 6. Dahl, Östen. Grammaticalization in the North: Noun phrase morphosyntax in Scandinavian vernaculars. 7. Schackow, Diana. A grammar of Yakkha. 8. Liljegren, Henrik. A grammar of Palula. 9. Shimelman, Aviva. A grammar of Yauyos Quechua. 10. Rudin, Catherine & Bryan James Gordon (eds.). Advances in the study of Siouan languages and linguistics. 11. Kluge, Angela. A grammar of Papuan Malay. 12. Kieviet, Paulus. A grammar of Rapa Nui. 13. Michaud, Alexis. Tone in Yongning Na: Lexical tones and morphotonology. 14. Enfield, N. J (ed.). Dependencies in language: On the causal ontology of linguistic systems. 15. Gutman, Ariel. Attributive constructions in North-Eastern Neo-Aramaic. 16. Bisang, Walter & Andrej Malchukov (eds.). Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios. ISSN: 2363-5568 Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios Edited by Walter Bisang Andrej Malchukov language science press Walter Bisang & Andrej Malchukov (eds.). 2017. Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios (Studies in Diversity Linguistics -

Overt Pronouon Constraint Effects in Second Lanugage Japanese

Overt Pronoun Constraint effects in second language Japanese Tokiko Okuma Department of Linguistics McGill University Montreal, Quebec April 2, 2015 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY © Copyright by Tokiko Okuma 2014 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT This dissertation investigates the applicability of the Full Transfer/Full Access hypothesis (FT/FA) (Schwartz & Sprouse, 1994, 1996) by investigating the interpretation of the Japanese pronoun (kare ‘he’) by adult English and Spanish speaking learners of Japanese. The Japanese, Spanish, and English languages differ with respect to interpretive properties of pronouns. In Japanese and Spanish, overt pronouns disallow a bound variable interpretation in subject and object positions. By contrast, In English, overt pronouns may have a bound variable interpretation in these positions. This is called the Overt Pronoun Constraint (OPC) (Montalbetti, 1984). The FT/FA model suggests that the initial state of L2 grammar is the end state of L1 grammar and that the restructuring of L2 grammar occurs with L2 input. This hypothesis predicts that L1 English speakers of L2 Japanese would initially allow a bound variable interpretation of Japanese pronouns in subject and object positions, transferring from their L1s. Nevertheless, they will successfully come to disallow a bound variable interpretation as their proficiency improves. In contrast, L1 Spanish speakers of L2 Japanese would correctly disallow a bound variable interpretation of Japanese pronouns in subject and object positions from the beginning. In order to test these predictions, L1 English and L1 Spanish speakers of L2 Japanese at intermediate and advanced levels of proficiency were compared with native Japanese speakers in their interpretations of pronouns with quantified i antecedents in two tasks. -

Cultural Orientation | Arabic-Iraqi

ARABIC-IRAQI Al Faw Palace or Water Palace, Baghdad Flickr / Jeremy Taylor DLIFLC DEFENSE LANGUAGE INSTITUTE FOREIGN LANGUAGE CENTER CULTURAL ORIENTATION | ARABIC-IRAQI TABLE OF CONTENT Profile Introduction ................................................................................................................... 6 Geography .................................................................................................................... 7 Geographic Divisions and Topographic Features .................................................. 7 Desert ....................................................................................................................7 Upper Tigris and Euphrates Upland .................................................................8 Northeast Highlands ...........................................................................................8 Alluvial Plains .......................................................................................................9 Climate ........................................................................................................................... 9 Rivers and Lakes ........................................................................................................10 Tigris River ..........................................................................................................10 Euphrates River ................................................................................................10 Shatt al-Arab .....................................................................................................