Certain Rare-Earth Magnets and Magnetic Materials and Articles Containing Same

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Relationship Between Microstructure and Magnetic Properties of Alnico Alloys

The relationship between microstructure and magnetic properties of alnico alloys Citation for published version (APA): Vos, de, K. J. (1966). The relationship between microstructure and magnetic properties of alnico alloys. Technische Hogeschool Eindhoven. https://doi.org/10.6100/IR287613 DOI: 10.6100/IR287613 Document status and date: Published: 01/01/1966 Document Version: Publisher’s PDF, also known as Version of Record (includes final page, issue and volume numbers) Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. -

Solidification of Immiscible Alloys Under High Magnetic Field

metals Review Solidification of Immiscible Alloys under High Magnetic Field: A Review Chen Wei 1, Jun Wang 1,*, Yixuan He 1, Jinshan Li 1,* and Eric Beaugnon 2 1 State Key Laboratory of Solidification Processing, Northwestern Polytechnical University, Xi’an 710072, China; [email protected] (C.W.); [email protected] (Y.H.) 2 INSA Toulouse, University Grenoble Alpes, University Toulouse Paul Sabatier, EMFL, CNRS, LNCMI, 38000 Grenoble, France; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (J.W.); [email protected] (J.L.) Abstract: Immiscible alloy is a kind of functional metal material with broad application prospects in industry and electronic fields, which has aroused extensive attention in recent decades. In the solidification process of metallic material processing, various attractive phenomena can be realized by applying a high magnetic field (HMF), including the nucleation and growth of alloys and mi- crostructure evolution, etc. The selectivity provided by Lorentz force, thermoelectric magnetic force, and magnetic force or a combination of magnetic field effects can effectively control the solidification process of the melt. Recent advances in the understanding of the development of immiscible alloys in the solidification microstructure induced by HMF are reviewed. In this review, the immiscible alloy systems are introduced and inspected, with the main focus on the relationship between the migration behavior of the phase and evolution of the solidification microstructure under HMF. Special attention is paid to the mechanism of microstructure evolution caused by the magnetic field and its influence on performance. The ability of HMF to overcome microstructural heterogeneity in the solidification Citation: Wei, C.; Wang, J.; He, Y.; Li, process provides freedom to design and modify new functional immiscible materials with desired J.; Beaugnon, E. -

Exploration of Alnico Permanent Magnet Microstructure And

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2018 Exploration of Alnico permanent magnet microstructure and processing for near final shape magnets with solid-state grain alignment for improved properties Aaron Gregory Kassen Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Materials Science and Engineering Commons, and the Mechanics of Materials Commons Recommended Citation Kassen, Aaron Gregory, "Exploration of Alnico permanent magnet microstructure and processing for near final shape magnets with solid-state grain alignment for improved properties" (2018). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 16390. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/16390 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Exploration of Alnico permanent magnet microstructure and processing for near final shape magnets with solid-state grain alignment for improved properties by Aaron Gregory Kassen A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Materials Science & Engineering Program of Study Committee: Iver E. Anderson, Major Professor Scott Chumbley David C. Jiles Matthew J. Kramer Alan M. Russell The student author, whose presentation of the scholarship herein was approved by the program of study committee, is solely responsible for the content of this dissertation. The Graduate College will ensure this dissertation is globally accessible and will not permit alterations after a degree is conferred. -

Development of Radically Enhanced Alnico Magnets (Dream) for Traction Drive Motors Iver E

Development of Radically Enhanced alnico Magnets (DREaM) for Traction Drive Motors Iver E. Anderson (PI) Matthew J. Kramer (Co-PI) Ames Laboratory (USDOE) June 19, 2018 Project ID # ELT015 This presentation does not contain any proprietary, confidential, or otherwise restricted information Overview Barriers & Targets* . High energy density permanent magnets (PM) needed for compact, and power Timeline density >50 kW/L). Reduced cost (<$3.3/kW): Efficient (>94%) • Start – October 2014 motors require aligned magnets with net- shape and simplified mass production. • Finish - September 2018 . RE Minerals: Rising prices of rare earth 85% Complete (RE) elements, price instability, and looming shortage, especially Dy. Performance & Lifetime: High temperature Budget tolerance (180-200˚C) and long life (15 yrs.) needed for magnets in PM motors. • Total funding - DOE share 100% • FY 17 Funding - $1400K Partners • Baldor, Carpenter, U. Wisconsin, • FY 18 (plan) Funding - $700K NREL, Ford, GM, UQM, (collaborators) • ORNL, U. Nebraska, Arnold Magnetic Tech. (DREaM subcontractors) • Project lead: Ames Lab *2025 VT Targets 2 Project Relevance/Objectives To meet 2025 goals for enhanced specific power, power density, and reduced (stable) cost with mass production capability for advanced electric drive motors, improved alloys and processing of permanent magnets (PM) must be developed. Likely rising RE cost trend and unpredictable import quotas (by China) for RE supplies (particularly Dy) motivates this research effort to improve (Fe-Co)-based alnico permanent magnet alloys (with reduced Co) and processing methods to achieve high magnetic strength (especially coercivity) for high torque drive motors. Objectives for the fully developed PM material: Provide competitive performance in advanced drive motors, compared to IPM motors with RE-PM. -

Stirring___Mixing__Shaking___H

MAGNETIC STIRRER - “with hot plate” Explosion proof, maintenance free brushless DC motor with low noise level offers a stirring volume up to 20 lt with a smooth start and quick stop. Ceramic top plate guarantees perfect chemical resistance against acids. Also provides impact resistant, easily cleanable, scratch proof surface with excellent heat distribution. Integrated design of the heater and the top plate provides excellent heat transfer rate and quick heat up capability. Hermetically sealed aluminium alloy housing protects all mechanical and electronic components from aggressive effects and guarantees safety with a long life time. Electronic speed control from 100 to 1500 rpm provides a gentle revolution and precise stirring speed. PID temperature technology enables excellent heating control from ambient temperature to 550°C. Offers integrated temperature control (+/- 0,2°C accuracy) with external PT1000 temperature sensor and support rod. Overheat protection circuit turns off the heater if the top plate temperature reaches 580°C for any reason. Hot surface warning display indicates any residual heat even if switched off. LCD display will show “HOT” if hotplate temperature is over 50°C. Large LCD panel for simultaneous display for set & actual temperature and set & actual speed. Special software enables control and documentation of all values via RS232 interface. Supplied complete with PT1000 temperature sensor, support rod and fixing clamp. Explosion proof, maintenance free catalogue number 613.06.001 brushless DC motor with low noise level offers a stirring volume up to 20 dimensions / weight (mm / kg) 215 x 360 x 112 / 5,3 lt with a smooth start and quick stop. -

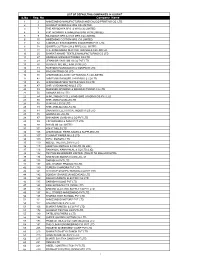

S.No Reg. No Company Name 1 2 AHMEDABAD MANUFACTURING and CALICO PRINTING CO

LIST OF DEFAULTING COMPANIES IN GUJRAT S.No Reg. No Company_Name 1 2 AHMEDABAD MANUFACTURING AND CALICO PRINTING CO. LTD. 2 3 GUJARAT GINNING & MFG CO.LIMITED. 3 7 THE ARYODAYA SPG & WVG.CO.LIMITED. 4 8 40817HCHOWK & AHMEDABAD MFG CO.LIMITED. 5 9 RAJNAGAR SPG & WVG MFG.CO.LIMITED. 6 10 HMEDABAD COTTON MFG. CO.LIMITED. 7 12 12DISPLAY STATUSSTEEL INDUSTRIES PVT. LTD. 8 18 ISHWER COTTON G.N.& PRES.CO.LIMITED. 9 22 THE AHMEDABAD NEW COTTON MILLS CO.LIMITED. 10 25 BHARAT KHAND TEXTILE MANUFACTURING CO LTD 11 27 HIMABHAI MANUFACTURING CO LTD 12 29 JEHANGIR VAKIL MILLS CO PVT LTD 13 30 GUJARAT OIL MILL & MFG CO LTD 14 31 RUSTOMJI MANGALDAS & COMPANY LTD 15 34 FINE KNITTING CO LTD 16 40 AHMEDABAD LAXMI COTTON MILLS CO.LIMITED. 17 42 AHMEDABAD KAISER-I-HIND MILLS CO LTD 18 45 AHMEDABAD NEW TEXTILE MILS CO LTD 19 47 SHRI VIVEKANAND MILLS LTD 20 49 MARSDEN SPINNING & MANUFACTURING CO LTD 21 50 ASHOKA MILLS LTD. 22 54 AHMEDABAD CYCLE & MOTORS TRADING CO PVT LTD 23 68 SHRI AMRUTA MILLS LTD 24 78 VIJAY MILLS CO LTD 25 79 SHRI ARBUDA MILLS LTD. 26 81 DHARWAR ELECTRICAL INDUSTRIES LTD 27 85 ANANTA MILLS LTD 28 87 BHIKABHAI JIVABHAI & CO PVT LTD 29 89 J R VAKHARIA & SONS PVT LTD 30 99 BIHARI MILLS LIMITED 31 101 ROHIT MILLS LTD 32 106 AHMEDABAD FIBRE-SALES & SUPPLIES LTD 33 107 GUJARAT PAPER MILLS LTD 34 109 IDEAL MOTORS LTD 35 110 MODEL THEATRES PVT LTD 36 115 HIMATLAL MOTILAL & CO LTD.(IN LIQ.) 37 116 RAMANLAL KANAIYALAL & CO LTD.(LIQ). -

Electrical and Magnetic Properties of Metals

\ 396-4 V) PUBLICATION a NBS SPECIAL / / National Bureau of Standards U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS The National Bureau of Standards' was established by an act of Congress March 3, 1901. The Bureau's overall goal is to strengthen and advance the Nation's science and technology and facilitate their effective application for public benefit. To this end, the Bureau conducts research and provides: (I) a basis lor the Nation's physical measurement system, (2) scientific and technological services for industry and government, (3) a technical basis for equity in trade, and 14) technical services to promote public safety. The Bureau consists of the Institute for Basic Standards, the Institute for Materials Research, the Institute for Applied Technology, the Institute for Computer Sciences and Technology, and the Office for Information Programs. THE INSTITUTE FOR BASIC STANDARDS provides the central basis within the United States of a complete and consistent system of physical measurement: coordinates that system with measurement systems of other nations; and furnishes essential services leading to accurate and uniform physical measurements throughout the Nation's scientific community, industry, and commerce. The Institute consists of the Office of Measurement Services, the Office of Radiation Measurement and the following Center and divisions: Applied Mathematics — Electricity — Mechanics — Heat — Optical Physics — Center " for Radiation Research: Nuclear Sciences; Applied Radiation — Laboratory Astrophysics — Cryogenics - — Electromagnetics - — Time and Frequency '-'. THE INSTITUTE FOR MATERIALS RESEARCH conducts materials research leading to improved methods of measurement, standards, and data on the properties of well-characterized materials needed by industry, commerce, educational institutions, and Government; provides advisory and research services to other Government agencies; and develops, produces, and distributes standard reference materials. -

Inorganic Chemistry

INORGANIC CHEMISTRY MINERAL : The natural substance in which the metal occurs in its native state or combined state in earth’s crust is known as mineral. Example: Al2O3.2H2O (Bauxite) is a mineral of Al. ORE : The mineral from which metals can be extracted conveniently and economically is called ore For example: Bauxite (Al2O3.2H2O) is also the ore of Al because it can be extracted easily and profitably. Note:- All ores are minerals, but all minerals are not ores. Distinction between Minerals and Ores ORES MINERALS 1.The minerals from which metals can 1. The natural occurring substances in which be extracted conveniently and metals economically present in native state or combined state. 2. All ores are minerals. 2. All minerals are not ores. 3. Extraction of metals from ores 3. Extraction of metals from minerals is is convenient and profitable. difficult and non-profitable. 4. Example: Bauxite (Al2O3. 2H2O) is an ore 4. Example: Clay (Al2O3.2SiO2.2H2O) is a of Aluminum. mineral of Aluminum. 1 EXTRACTION OF METALS: METALLURGY The process of extraction of metals from their ores is called metallurgy. The general methods of extraction of metals are: 1. Crushing and Grinding of ore 2. Concentration of ore or Ore Dressing 3. Oxidation 4. Reduction 5. Refining 2 1. CRUSHING AND GRINDING OF ORE The ores obtained from mines are in the form of big lumps. These are first crushed into small pieces with the help of jaw crusher or grinder. Then these pieces are converted to fine powder form with the help of ball mill or stamp mill. -

Nickel and Its Alloys

National Bureau of Standards Library, E-01 Admin. Bldg. IHW 9 1 50CO NBS MONOGRAPH 106 Nickel and Its Alloys U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS THE NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS The National Bureau of Standards^ provides measurement and technical information services essential to the efficiency and effectiveness of the work of the Nation's scientists and engineers. The Bureau serves also as a focal point in the Federal Government for assuring maximum application of the physical and engineering sciences to the advancement of technology in industry and commerce. To accomplish this mission, the Bureau is organized into three institutes covering broad program areas of research and services: THE INSTITUTE FOR BASIC STANDARDS . provides the central basis within the United States for a complete and consistent system of physical measurements, coordinates that system with the measurement systems of other nations, and furnishes essential services leading to accurate and uniform physical measurements throughout the Nation's scientific community, industry, and commerce. This Institute comprises a series of divisions, each serving a classical subject matter area: —Applied Mathematics—Electricity—Metrology—Mechanics—Heat—Atomic Physics—Physical Chemistry—Radiation Physics—Laboratory Astrophysics^—Radio Standards Laboratory,^ which includes Radio Standards Physics and Radio Standards Engineering—Office of Standard Refer- ence Data. THE INSTITUTE FOR MATERIALS RESEARCH . conducts materials research and provides associated materials services including mainly reference materials and data on the properties of ma- terials. Beyond its direct interest to the Nation's scientists and engineers, this Institute yields services which are essential to the advancement of technology in industry and commerce. -

Properties of Some Metals and Alloys

Properties of Some Metals and Alloys COPPER AND COPPER ALLOYS • WHITE METALS AND ALLOYS • ALUMINUM AND ALLOYS • MAGNESIUM ALLOYS • TITANIUM ALLOYS • RESISTANCE HEATING ALLOYS • MAGNETIC ALLOYS • CON- TROLLED EXPANSION AND CON- STANT — MODULUS ALLOYS • NICKEL AND ALLOYS • MONEL* NICKEL- COPPER ALLOYS • INCOLOY* NICKEL- IRON-CHROMIUM ALLOYS • INCONEL* NICKEL-CHROMIUM-IRON ALLOYS • NIMONIC* NICKEL-CHROMIUM ALLOYS • HASTELLOY* ALLOYS • CHLORIMET* ALLOYS • ILLIUM* ALLOYS • HIGH TEMPERATURE-HIGH STRENGTH ALLOYS • IRON AND STEEL ALLOYS • CAST IRON ALLOYS • WROUGHT STAINLESS STEEL • CAST CORROSION AND HEAT RESISTANT ALLOYS* REFRACTORY METALS AND ALLOYS • PRECIOUS METALS Copyright 1982, The International Nickel Company, Inc. Properties of Some Metals INTRODUCTION The information assembled in this publication has and Alloys been obtained from various sources. The chemical compositions and the mechanical and physical proper- ties are typical for the metals and alloys listed. The sources that have been most helpful are the metal and alloy producers, ALLOY DIGEST, WOLDMAN’S ENGI- NEERING ALLOYS, International Nickel’s publications and UNIFIED NUMBERING SYSTEM for METALS and ALLOYS. These data are presented to facilitate general compari- son and are not intended for specification or design purposes. Variations from these typical values can be expected and will be dependent upon mill practice and material form and size. Strength is generally higher, and ductility correspondingly lower, in the smaller sizes of rods and bars and in cold-drawn wire; the converse is true for the larger sizes. In the case of carbon, alloy and hardenable stainless steels, mechanical proper- ties and hardnesses vary widely with the particular heat treatment used. REFERENCES Many of the alloys listed in this publication are marketed under well-known trademarks of their pro- ducers, and an effort has been made to associate such trademarks with the applicable materials listed herein. -

Randall M. German Fundamentals and Applications

Randall M. German Particulate Composites Fundamentals and Applications Particulate Composites Randall M. German Particulate Composites Fundamentals and Applications Randall M. German San Diego State University San Diego, CA, USA ISBN 978-3-319-29915-0 ISBN 978-3-319-29917-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-29917-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016933672 © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Printed on acid-free paper This Springer imprint is published by Springer Nature The registered company is Springer International Publishing AG Switzerland Dedicated to John Lee Johnson Preface Engineering materials continue to encounter challenges for new property combi- nations, and these challenges are leading to many hybrid materials known as composites. -

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

Particle shape anisotropy and its effects in AlNiCo and Fe-Cr-Co magnet alloys. GRAY, P. Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/19715/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/19715/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. 78177880 :L4- Sheffield City Polytechnic Eric Mensforth Library REFERENCE ONLY This book must not be taken from the Library PL/26 R5193 ProQuest Number: 10697017 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10697017 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 PARTICLE SHAPE