The Evolution of the Holy See's Institutions for Order in Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plenary Indulgence

Our Lady of Lourdes Hospitality North American Volunteers Pope Francis Proclaims Plenary Indulgence Affirming the Response to the PAENITENIARIA 10th Year Jubilee Plenary Indulgence Honoring Our Lady of Lourdes Hospitality North American Volunteers, by Apostolic Papal Decree a Plenary Indulgence is granted to faithful making pilgrimage to Lourdes or experiencing Lourdes in a Virtual Pilgrimage with North American Lourdes Volunteers by fulfilling the usual norms and conditions between July 16, 2013 thru July 15, 2020. APOSTOLICA Jesus Christ lovingly sacrificed Himself for the salvation of humanity. Through Baptism, we are freed from the Original Sin of disobedience inherited from Adam and Eve. With our gift of free will we can choose to sin, personally separating ourselves from God. Although we can be completely forgiven, temporal (temporary) consequences of sin remain. Indulgences are special graces that can rid us of temporal punishment. What is a plenary indulgence? “An indulgence is a remission before God of the temporal punishment Our Lady of Lourdes Hospitality North American Volunteers due to sins whose guilt has already been forgiven.” (CCC 1471) There Public Association of the Christian Faithful and First Hospitality of the Americas are two types of indulgences: plenary and partial. A plenary indulgence www.LourdesVolunteers.org [email protected] removes all of the temporal punishment due to sin; a partial indulgence (315) 476-0026 FAX (419) 730-4540 removes some but not all of the temporal punishment. © 2017 V. 1-18 What is temporal punishment for sin? How can the Church give indulgences? Temporal punishment for sin is the sanctification from attachment to sin, The Church is able to grant indulgences by the purification to holiness needed for us to be able to enter Heaven. -

The Official Catholic Directory® 2016, Part II

PRINT MEDIA KIT The Offi cial Catholic Directory® 2016, Part II 199 Years of Service to the Catholic Church ABOUT THE OFFICIAL CATHOLIC DIRECTORY Historically known as The Kenedy Directory, The O cial Catholic Directory is undeniably the most extensive and authoritative source of data available on the Catholic Church in the U.S. This 2-volume set is universally recognized and widely used by clergy and professionals in the Catholic Church and its institutions (parishes, schools, universities, hospitals, care centers and more). DISTRIBUTION Reservation Deadline: The O cial Catholic Directory 2016, Part II, to be published in December October 3, 2016 2016, will be sold and distributed to nearly 9,000 priests, parishes, (arch)dioceses, Materials Due: educational and other institutions, and has a reach of well over 30,000 clergy and October 10, 2016 other professionals. This includes a ‘special honorary distribution’ to members of the church hierarchy – every active Cardinal, Archbishop, Bishop and Chancery Offi ce in Publication Date: the U.S. December 2016 REACH THIS HIGHLY TARGETED AUDIENCE • Present your product or service to a highly targeted audience with purchasing power. • Reach over 30,000 Catholic clergy and professionals across the U.S. • Attain year-round access to decision makers. • Gain recognition in this highly respected publication used throughout the Catholic Church and its institutions. • Enjoy a FREE ONLINE LISTING in our Products & Services Guide with your print advertising http://www.offi cialcatholicdirectory.com/mp/index.php. • Place your advertising message directly into the hands of our readers via our outsert program. “Th e Offi cial Catholic Directory is an indispensible tool for keeping up to date with the church in the U.S. -

KAS International Reports 10/2015

38 KAS INTERNATIONAL REPORTS 10|2015 MICROSTATE AND SUPERPOWER THE VATICAN IN INTERNATIONAL POLITICS Christian E. Rieck / Dorothee Niebuhr At the end of September, Pope Francis met with a triumphal reception in the United States. But while he performed the first canonisation on U.S. soil in Washington and celebrated mass in front of two million faithful in Philadelphia, the attention focused less on the religious aspects of the trip than on the Pope’s vis- its to the sacred halls of political power. On these occasions, the Pope acted less in the role of head of the Church, and therefore Christian E. Rieck a spiritual one, and more in the role of diplomatic actor. In New is Desk officer for York, he spoke at the United Nations Sustainable Development Development Policy th and Human Rights Summit and at the 70 General Assembly. In Washington, he was in the Department the first pope ever to give a speech at the United States Congress, of Political Dialogue which received widespread attention. This was remarkable in that and Analysis at the Konrad-Adenauer- Pope Francis himself is not without his detractors in Congress and Stiftung in Berlin he had, probably intentionally, come to the USA directly from a and member of visit to Cuba, a country that the United States has a difficult rela- its Working Group of Young Foreign tionship with. Policy Experts. Since the election of Pope Francis in 2013, the Holy See has come to play an extremely prominent role in the arena of world poli- tics. The reasons for this enhanced media visibility firstly have to do with the person, the agenda and the biography of this first non-European Pope. -

On the Threshold of the Holocaust: Anti-Jewish Riots and Pogroms In

Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 11 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Szarota Tomasz On the Threshold of the Holocaust In the early months of the German occu- volume describes various characters On the Threshold pation during WWII, many of Europe’s and their stories, revealing some striking major cities witnessed anti-Jewish riots, similarities and telling differences, while anti-Semitic incidents, and even pogroms raising tantalising questions. of the Holocaust carried out by the local population. Who took part in these excesses, and what was their attitude towards the Germans? The Author Anti-Jewish Riots and Pogroms Were they guided or spontaneous? What Tomasz Szarota is Professor at the Insti- part did the Germans play in these events tute of History of the Polish Academy in Occupied Europe and how did they manipulate them for of Sciences and serves on the Advisory their own benefit? Delving into the source Board of the Museum of the Second Warsaw – Paris – The Hague – material for Warsaw, Paris, The Hague, World War in Gda´nsk. His special interest Amsterdam, Antwerp, and Kaunas, this comprises WWII, Nazi-occupied Poland, Amsterdam – Antwerp – Kaunas study is the first to take a comparative the resistance movement, and life in look at these questions. Looking closely Warsaw and other European cities under at events many would like to forget, the the German occupation. On the the Threshold of Holocaust ISBN 978-3-631-64048-7 GEP 11_264048_Szarota_AK_A5HC PLE edition new.indd 1 31.08.15 10:52 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 11 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Szarota Tomasz On the Threshold of the Holocaust In the early months of the German occu- volume describes various characters On the Threshold pation during WWII, many of Europe’s and their stories, revealing some striking major cities witnessed anti-Jewish riots, similarities and telling differences, while anti-Semitic incidents, and even pogroms raising tantalising questions. -

A Pope of Their Own

Magnus Lundberg A Pope of their Own El Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church UPPSALA STUDIES IN CHURCH HISTORY 1 About the series Uppsala Studies in Church History is a series that is published in the Department of Theology, Uppsala University. The series includes works in both English and Swedish. The volumes are available open-access and only published in digital form. For a list of available titles, see end of the book. About the author Magnus Lundberg is Professor of Church and Mission Studies and Acting Professor of Church History at Uppsala University. He specializes in early modern and modern church and mission history with focus on colonial Latin America. Among his monographs are Mission and Ecstasy: Contemplative Women and Salvation in Colonial Spanish America and the Philippines (2015) and Church Life between the Metropolitan and the Local: Parishes, Parishioners and Parish Priests in Seventeenth-Century Mexico (2011). Personal web site: www.magnuslundberg.net Uppsala Studies in Church History 1 Magnus Lundberg A Pope of their Own El Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church Lundberg, Magnus. A Pope of Their Own: Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church. Uppsala Studies in Church History 1.Uppsala: Uppsala University, Department of Theology, 2017. ISBN 978-91-984129-0-1 Editor’s address: Uppsala University, Department of Theology, Church History, Box 511, SE-751 20 UPPSALA, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected]. Contents Preface 1 1. Introduction 11 The Religio-Political Context 12 Early Apparitions at El Palmar de Troya 15 Clemente Domínguez and Manuel Alonso 19 2. -

3Rd Sunday in Ordinary Time-Year B 24Th January 2021

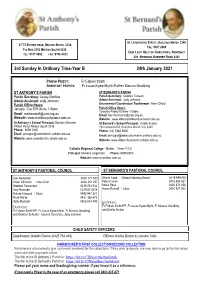

61 LERDERDERG STREET, BACCHUS MARSH 3340 67-75 EXFORD ROAD, MELTON SOUTH, 3338. TEL: 5367 2069 P.O BOX 2152 MELTON SOUTH 3338 OUR LADY HELP OF CHRISTIANS, KOROBEIT TEL: 9747 9692 FAX: 9746 0422 309 MYRNIONG-KOROBEIT ROAD 3341 3rd Sunday In Ordinary Time-Year B 24th January 2021 PARISH PRIEST: Fr Fabian Smith ASSISTANT PRIESTS: Fr Lucas Kyaw Myint /Father Marcus Goulding ST ANTHONY’S PARISH ST BERNARD’S PARISH Parish Secretary: Lesley Morffew Parish Secretary: Dolores Turcsan Admin Assistant: Judy Johnson Admin Assistant: Judy Johnson Parish Office Hours: Sacramental Coordinator/ Bookkeeper: Naim Chdid January :Tue-Fri9.00am-1.00pm Parish Office Hours: Tuesday-Friday 9.00am-1.00pm Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: www.stanthonyof padua.com.au Website: www.stbernardsbacchusmarsh.com.au St Anthony’s School Principal: Damien Schuster St Bernard’s School Principal: Emilio Scalzo Wilson Road, Melton South 3338 19a Gisborne Rd, Bacchus Marsh VIC 3340 Phone: 8099 7800 Phone: (03) 5366 5800 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: www.sameltonsth.catholic.edu.au Website: www.sbbacchusmarsh.catholic.edu.au Catholic Regional College - Melton (Years 7-12) Principal: Marlene Jorgensen Phone: 8099 6000 Website: www.crcmelton.com.au ST ANTHONY’S PASTORAL COUNCIL ST BERNARD’S PASTORAL COUNCIL Sue Alexander 0400 171 843 Shane Cook -School Advisory Board 0419 999 052 Lillian Christian - Vice Chair 0400 441 257 Peter Farren 0418 594 501 Stephen Fernandes 0439 -

Newsletter 2020 I

NEWSLETTER EMBASSY OF MALAYSIA TO THE HOLY SEE JAN - JUN 2020 | 1ST ISSUE 2020 INSIDE THIS ISSUE • Message from His Excellency Westmoreland Palon • Traditional Exchange of New Year Greetings between the Holy Father and the Diplomatic Corp • Malaysia's contribution towards Albania's recovery efforts following the devastating earthquake in November 2019 • Meeting with Archbishop Ian Ernest, the Archbishop of Canterbury's new Personal Representative to the Holy See & Director of the Anglican Centre in Rome • Visit by Secretary General of the Ministry of Water, Land and Natural Resources • A Very Warm Welcome to Father George Harrison • Responding to COVID-19 • Pope Called for Joint Prayer to End the Coronavirus • Malaysia’s Diplomatic Equipment Stockpile (MDES) • Repatriation of Malaysian Citizens and their dependents from the Holy See and Italy to Malaysia • A Fond Farewell to Mr Mohd Shaifuddin bin Daud and family • Selamat Hari Raya Aidilfitri & Selamat Hari Gawai • Post-Lockdown Gathering with Malaysians at the Holy See Malawakil Holy See 1 Message From His Excellency St. Peter’s Square, once deserted, is slowly coming back to life now that Italy is Westmoreland Palon welcoming visitors from neighbouring countries. t gives me great pleasure to present you the latest edition of the Embassy’s Nonetheless, we still need to be cautious. If Inewsletter for the first half of 2020. It has we all continue to do our part to help flatten certainly been a very challenging year so far the curve and stop the spread of the virus, for everyone. The coronavirus pandemic has we can look forward to a safer and brighter put a halt to many activities with second half of the year. -

The Catholic Church in the Czech Republic

The Catholic Church in the Czech Republic Dear Readers, The publication on the Ro- man Catholic Church which you are holding in your hands may strike you as history that belongs in a museum. How- ever, if you leaf through it and look around our beauti- ful country, you may discover that it belongs to the present as well. Many changes have taken place. The history of the Church in this country is also the history of this nation. And the history of the nation, of the country’s inhabitants, always has been and still is the history of the Church. The Church’s mission is to serve mankind, and we want to fulfil Jesus’s call: “I did not come to be served but to serve.” The beautiful and unique pastoral constitution of Vatican Coun- cil II, the document “Joy and Hope” begins with the words: “The joys and the hopes, the grief and the anxieties of the men of this age, especially those who are poor or in any way afflicted, these are the joys and hopes, the grief and anxieties of the followers of Christ.” This is the task that hundreds of thousands of men and women in this country strive to carry out. According to expert statistical estimates, approximately three million Roman Catholics live in our country along with almost twenty thousand of our Eastern broth- ers and sisters in the Greek Catholic Church, with whom we are in full communion. There are an additional million Christians who belong to a variety of other Churches. Ecumenical cooperation, which was strengthened by decades of persecution and bullying of the Church, is flourishing remarkably in this country. -

The Holy See

The Holy See I GENERAL NORMS Notion of Roman Curia Art. 1 — The Roman Curia is the complex of dicasteries and institutes which help the Roman Pontiff in the exercise of his supreme pastoral office for the good and service of the whole Church and of the particular Churches. It thus strengthens the unity of the faith and the communion of the people of God and promotes the mission proper to the Church in the world. Structure of the Dicasteries Art. 2 — § 1. By the word "dicasteries" are understood the Secretariat of State, Congregations, Tribunals, Councils and Offices, namely the Apostolic Camera, the Administration of the Patrimony of the Apostolic See, and the Prefecture for the Economic Affairs of the Holy See. § 2. The dicasteries are juridically equal among themselves. § 3. Among the institutes of the Roman Curia are the Prefecture of the Papal Household and the Office for the Liturgical Celebrations of the Supreme Pontiff. Art. 3 — § 1. Unless they have a different structure in virtue of their specific nature or some special law, the dicasteries are composed of the cardinal prefect or the presiding archbishop, a body of cardinals and of some bishops, assisted by a secretary, consultors, senior administrators, and a suitable number of officials. § 2. According to the specific nature of certain dicasteries, clerics and other faithful can be added to the body of cardinals and bishops. § 3. Strictly speaking, the members of a congregation are the cardinals and the bishops. 2 Art. 4. — The prefect or president acts as moderator of the dicastery, directs it and acts in its name. -

Events of the Reformation Part 1 – Church Becomes Powerful Institution

May 20, 2018 Events of the Reformation Protestants and Roman Catholics agree on first 5 centuries. What changed? Why did some in the Church want reform by the 16th century? Outline Why the Reformation? 1. Church becomes powerful institution. 2. Additional teaching and practices were added. 3. People begin questioning the Church. 4. Martin Luther’s protest. Part 1 – Church Becomes Powerful Institution Evidence of Rome’s power grab • In 2nd century we see bishops over regions; people looked to them for guidance. • Around 195AD there was dispute over which day to celebrate Passover (14th Nissan vs. Sunday) • Polycarp said 14th Nissan, but now Victor (Bishop of Rome) liked Sunday. • A council was convened to decide, and they decided on Sunday. • But bishops of Asia continued the Passover on 14th Nissan. • Eusebius wrote what happened next: “Thereupon Victor, who presided over the church at Rome, immediately attempted to cut off from the common unity the parishes of all Asia, with the churches that agreed with them, as heterodox [heretics]; and he wrote letters and declared all the brethren there wholly excommunicate.” (Eus., Hist. eccl. 5.24.9) Everyone started looking to Rome to settle disputes • Rome was always ending up on the winning side in their handling of controversial topics. 1 • So through a combination of the fact that Rome was the most important city in the ancient world and its bishop was always right doctrinally then everyone started looking to Rome. • So Rome took that power and developed it into the Roman Catholic Church by the 600s. Church granted power to rule • Constantine gave the pope power to rule over Italy, Jerusalem, Constantinople and Alexandria. -

Christiansen Papal Diplomacy Talk V2

Pope Francis and Vatican Diplomacy By Drew Christiansen, S.J. Christ Church—Episcopal, Georgetown, D.C. June 10, 2014 In a new book, Pietro Parollin, the Vatican secretary of state, predicted that we can expect new diplomatic initiatives from Pope Francis. The interreligious prayer service this past weekend in the Vatican gardens is an example of the Pope’s personal diplomacy as was the Day of Prayer for Peace last year in advance of the projected US bombing of Syrian chemical weapon sites. But Francis has also opted for a more forthright use of Vatican diplomacy, sending off Vatican diplomats at the time of the chemical weapons crisis and to last February’s Geneva conference on Syria. The collaboration with the Church of England on anti-trafficking programs is another example of his activist policy. In naming Parollin as secretary of state, the Holy Father also chose a man able to fulfill his aspirations for Vatican diplomacy. Cardinal Parollin is a modest man, a good listener, an effective negotiator and a Quiet but decisive policymaker. He made progress in opening relations with Vietnam, prepared the ground for an opening with China, and worked less successfully to conclude long-running negotiations with Israel. Pope Francis has also let it be known that the first step in the restructuring of the Roman Curia will be to focus the Secretariat of State on diplomatic affairs. That focus will not only be on symbolic religious events, though they have a role on which I will say something at the end, but also on more energetic diplomacy in the usual fora aimed at pragmatic results. -

Archbishop Joseph W. Tobin Archbishop Tobin Is Appointed Photos by Sean Gallagher Photos by Sixth Archbishop of Indianapolis

Our newInside shepherd See more coverage about this historic event on pages 9-12. Serving the ChurchCriterion in Central and Southern Indiana Since 1960 CriterionOnline.com October 26, 2012 Vol. LIII, No. 4 75¢ Welcome, Archbishop Joseph W. Tobin Archbishop Tobin is appointed Photos by Sean Gallagher Photos by sixth archbishop of Indianapolis By Sean Gallagher First of two parts The Archdiocese of Indianapolis has a new shepherd. On Oct. 18, Archbishop Joseph W. Tobin was appointed archbishop of Indianapolis by Pope Benedict XVI. He succeeds Archbishop Emeritus Daniel M. Buechlein, who served as the archdiocese’s spiritual leader for 19 years but was granted early retirement by the Holy Father because of health reasons last year. The new archbishop was formally introduced during a press conference at SS. Peter and Paul Cathedral in Indianapolis. (See related story on page 9.) Archbishop Tobin, 60, was born in Detroit and is the oldest of 13 children. He professed vows as a member of the Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer— a religious order more commonly known as Archbishop Joseph W. Tobin greets Hispanic Catholics after the Oct. 18 press conference at SS. Peter and Paul Cathedral in Indianapolis during which the Redemptorists—in 1973 and was he was introduced as the new archbishop of Indianapolis. Greeting him are, from left, Jesús Castillo, a member of St. Anthony Parish in Indianapolis; ordained a priest in 1978. Gloria Guillén, Hispanic ministry assistant for the archdiocesan Office of Multiculture Ministry; Juan Manuel Gúzman, pastoral associate at St. Mary From 1979-90, he ministered at Parish in Indianapolis; Jazmina Noguera, a member of St.