Armor School Pamphlet 360-2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Armor, July-August 1993 Edition

It‘s always inspiring for me to discover how an Army, and as a nation. And it is in the many people outside of active duty, national spirit of finding a better way that we feature guard, and reservists like to talk tanks. I can articles on call for fire, field trains security, be on-post, off-post, or at the post office, and and maneuver sketches among others. The once people find out what I do, they can’t historical articles herein provide balance and wait to share their views on armored warfare help us quantify our lessons learned. The or the latest in combat vehicle development. overview on Yugoslavia will set the scene for Sometimes their comments lead to a story for what promises to be a benchmark story com- ARMOR, often times not, but I always come ing in the September-October ARMOR - an away from the discussion edified. I’ve been in eyewitness to a tank battle in the Balkans. this job a year now, and I’ve heard every- So, we martial descendants of St. George thing from, “We need to up-gun the AI,” to keep sharpening our sword and polishing our “I’ve got this idea for how to armor as we await the next make a tank float on a challenge. And while there cushion of air ...” is no hunger for battle in Some of those notions the eyes of those who have about tank design crystal- truly seen it, there is a glint ized recently with our Tank of certainty that it will come Design Contest, sponsored nonetheless. -

Modern Application of Mechanized-Cavalry Groups for Cavalry Echelons Above Brigade by MAJ Joseph J

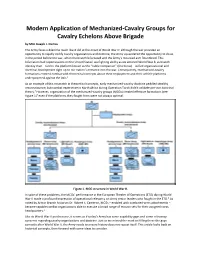

Modern Application of Mechanized-Cavalry Groups for Cavalry Echelons Above Brigade by MAJ Joseph J. Dumas The Army faces a dilemma much like it did at the onset of World War II: although the war provided an opportunity to rapidly codify cavalry organizations and doctrine, the Army squandered the opportunity to do so in the period before the war, when the branch bifurcated and the Army’s mounted arm floundered. This bifurcation had repercussions on the United States’ warfighting ability as we entered World War II, as branch identity then – tied to the platform known as the “noble companion” (the horse) – stifled organizational and doctrinal development right up to our nation’s entrance into the war. Consequently, mechanized-cavalry formations entered combat with theoretical concepts about their employment and their vehicle platforms underpowered against the Axis.1 As an example of this mismatch in theoretical concepts, early mechanized-cavalry doctrine peddled stealthy reconnaissance, but combat experience in North Africa during Operation Torch didn’t validate pre-war doctrinal theory.2 However, organization of the mechanized-cavalry groups (MCGs) created effective formations (see Figure 1)3 even if the platforms they fought from were not always optimal. Figure 1. MCG structure in World War II. In spite of these problems, the MCGs’ performance in the European Theater of Operations (ETO) during World War II made a profound impression of operational relevancy on Army senior leaders who fought in the ETO.4 As noted by Armor Branch historian Dr. Robert S. Cameron, MCGs – enabled with combined-arms attachments – became capable combat organizations able to execute a broad range of mission sets for their assigned corps headquarters.5 Like its World War II predecessor, it seems as if today’s Army has some capability gaps and some relevancy concerns regarding cavalry organizations and doctrine. -

Efes 2018 Combined Joint Live Fire Exercise

VOLUME 12 ISSUE 82 YEAR 2018 ISSN 1306 5998 A LOOK AT THE TURKISH DEFENSE INDUSTRY LAND PLATFORMS/SYSTEMS SECTOR EFES 2018 COMBINED JOINT LIVE FIRE EXERCISE PAKISTAN TO PROCURE 30 T129 ATAK HELICOPTER FROM TURKEY TURAF’S FIRST F-35A MAKES MAIDEN FLIGHT TURKISH DEFENCE & AEROSPACE INDUSTRIES 2017 PERFORMANCE REPORT ISSUE 82/2018 1 DEFENCE TURKEY VOLUME: 12 ISSUE: 82 YEAR: 2018 ISSN 1306 5998 Publisher Hatice Ayşe EVERS Publisher & Editor in Chief Ayşe EVERS 6 [email protected] Managing Editor Cem AKALIN [email protected] Editor İbrahim SÜNNETÇİ [email protected] Administrative Coordinator Yeşim BİLGİNOĞLU YÖRÜK [email protected] International Relations Director Şebnem AKALIN [email protected] Advertisement Director 30 Yasemin BOLAT YILDIZ [email protected] Translation Tanyel AKMAN [email protected] Editing Mona Melleberg YÜKSELTÜRK Robert EVERS Graphics & Design Gülsemin BOLAT Görkem ELMAS [email protected] Photographer Sinan Niyazi KUTSAL 46 Advisory Board (R) Major General Fahir ALTAN (R) Navy Captain Zafer BETONER Prof Dr. Nafiz ALEMDAROĞLU Cem KOÇ Asst. Prof. Dr. Altan ÖZKİL Kaya YAZGAN Ali KALIPÇI Zeynep KAREL DEFENCE TURKEY Administrative Office DT Medya LTD.STI Güneypark Kümeevleri (Sinpaş Altınoran) Kule 3 No:142 Çankaya Ankara / Turkey 58 Tel: +90 (312) 447 1320 [email protected] www.defenceturkey.com Printing Demir Ofis Kırtasiye Perpa Ticaret Merkezi B Blok Kat:8 No:936 Şişli / İstanbul Tel: +90 212 222 26 36 [email protected] www.demirofiskirtasiye.com Basım Tarihi Nisan - Mayıs 2018 Yayın Türü Süreli DT Medya LTD. ŞTİ. 74 © All rights reserved. -

The African American Soldier at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, 1892-1946

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Anthropology, Department of 2-2001 The African American Soldier At Fort Huachuca, Arizona, 1892-1946 Steven D. Smith University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/anth_facpub Part of the Anthropology Commons Publication Info Published in 2001. © 2001, University of South Carolina--South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology This Book is brought to you by the Anthropology, Department of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE AFRICAN AMERICAN SOLDIER AT FORT HUACHUCA, ARIZONA, 1892-1946 The U.S Army Fort Huachuca, Arizona, And the Center of Expertise for Preservation of Structures and Buildings U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Seattle District Seattle, Washington THE AFRICAN AMERICAN SOLDIER AT FORT HUACHUCA, ARIZONA, 1892-1946 By Steven D. Smith South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology University of South Carolina Prepared For: U.S. Army Fort Huachuca, Arizona And the The Center of Expertise for Preservation of Historic Structures & Buildings, U.S. Army Corps of Engineer, Seattle District Under Contract No. DACW67-00-P-4028 February 2001 ABSTRACT This study examines the history of African American soldiers at Fort Huachuca, Arizona from 1892 until 1946. It was during this period that U.S. Army policy required that African Americans serve in separate military units from white soldiers. All four of the United States Congressionally mandated all-black units were stationed at Fort Huachuca during this period, beginning with the 24th Infantry and following in chronological order; the 9th Cavalry, the 10th Cavalry, and the 25th Infantry. -

Cobra Strike! a Reality

By Spc. Jason Dangel, 4th BCT PAO, 4th Inf. Div. of operations with their ISF counterparts. The 4th Brigade Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division, Cobra combat support and combat service support units, "Cobras," deployed in late November 2005 in support of the 4th Special Troops Battalion and 704th Support Operation Iraqi Freedom and officially assumed responsibil- Battalion were responsible for command and control for all ity of battle space in central and southern Baghdad from the the units of Task Force Cobra, while simultaneously provid- 4th Brigade Combat Team, 3rd Infantry Division, Jan. 14, ing logistical support for the brigade's Soldiers. 2006. The 3rd Battalion, 67th Armor was attached to the 4th After a successful transition with the 3rd Inf. Div.'s Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division and operat- "Vanguard" Brigade, the Cobra Brigade was ready for its ed from FOB Rustamiyah, located in the northern portion of first mission in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom. the Iraqi capital. As the Ivy Division's newest brigade combat team, the The Cobra Brigade oversaw the security of many key events Cobra Brigade, comprised of approximately 5,000 combat- to include the first session of the Iraqi Council of ready Soldiers, was deployed to Forward Operating Base Representatives. Prosperity in Baghdad's International Zone and operated in The Iraqi Council of Representatives, the parliament some of the most dangerous neighborhoods in Baghdad, to elected under the nation's new constitution, convened at the include Al-Doura, Al-Amerriyah, Abu T'schir, Al-Ademiyah Parliament Center in central Baghdad where 275 representa- and Gazaliyah. -

Moscow Defense Brief 1/2005

CONTENTS War And People #1(3), 2005 Militant Islam in Russia – Potential for Conflict PUBLISHER 2 Centre for Arms Trade Analysis of Strategies and Financial Results of Russian Arms Trade With Foreign Technolog ies States in 2004 9 CAST Director & Editor Russian Arms Trade with Southeast Asia and The Republic Ruslan Pukhov of Korea 13 Advisory Editor Konstantin Makienko Defense Industry Researcher Ukraine’s Defense Industry: A Mirror of the Nation 19 Ruslan Aliev Researcher Russian Armed Forces Sergei Pokidov The Russian Military: Still Saving for a Rainy Day 23 Researcher Dmitry Vasiliev Space Editorial Office Russia, Moscow, 119334, Leninsky prospect, 45, suite 480 Russian-Indian Cooperation in Space 27 phone: +7 095 135 1378 fax: +7 095 775 0418 Armed Conflicts http://www.mdb.cast.ru/ To subscribe contact US Armor in Operation “Iraqi Freedom” 32 phone +7 095 135 1378 or e-mail: [email protected] Facts & Figures E-mail the editors: [email protected] Largest identified transfers of Russian arms in 2004 36 Moscow Defense Brief is published by the Centre for Analysis of Strategies and Technologies Identified contracts signed in 2004 37 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, Our Authors mechanical or photocopying, recording or other wise, without reference to Moscow Defense Brief. Please note that, while the Publisher has taken all reasonable care in the compilation of this publication, the Publisher cannot accept responsibility for any errors or omissions in this publication or -

BATTLE-SCARRED and DIRTY: US ARMY TACTICAL LEADERSHIP in the MEDITERRANEAN THEATER, 1942-1943 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial

BATTLE-SCARRED AND DIRTY: US ARMY TACTICAL LEADERSHIP IN THE MEDITERRANEAN THEATER, 1942-1943 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Steven Thomas Barry Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Allan R. Millett, Adviser Dr. John F. Guilmartin Dr. John L. Brooke Copyright by Steven T. Barry 2011 Abstract Throughout the North African and Sicilian campaigns of World War II, the battalion leadership exercised by United States regular army officers provided the essential component that contributed to battlefield success and combat effectiveness despite deficiencies in equipment, organization, mobilization, and inadequate operational leadership. Essentially, without the regular army battalion leaders, US units could not have functioned tactically early in the war. For both Operations TORCH and HUSKY, the US Army did not possess the leadership or staffs at the corps level to consistently coordinate combined arms maneuver with air and sea power. The battalion leadership brought discipline, maturity, experience, and the ability to translate common operational guidance into tactical reality. Many US officers shared the same ―Old Army‖ skill sets in their early career. Across the Army in the 1930s, these officers developed familiarity with the systems and doctrine that would prove crucial in the combined arms operations of the Second World War. The battalion tactical leadership overcame lackluster operational and strategic guidance and other significant handicaps to execute the first Mediterranean Theater of Operations campaigns. Three sets of factors shaped this pivotal group of men. First, all of these officers were shaped by pre-war experiences. -

Congressional Record- House. May 23

5868 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD- HOUSE. MAY 23, Homer B. Grant, of Massachusetts, late first lieutenant, Twenty Irwin G. Lukens, to be postmaster at North Wales, in the county sixth Infantry, United States Volunteers (now second lieutenant, of Montgomery and State of Pe..~ylvania. Artillery Corps, United States Army), to fill an original vacancy. Benjamin Jacobs, to be postmaster at Pencoyd, in the county John W. C. Abbott, at large, late first lieutenant, Thirtieth In of Montgomery and State of Pennsylvania. fantry, United States Volunteers (now second lieutenant, Artillery JohnS. Buchanan, to be postmaster at Ambler, in the county Corps, United States Army), to fill an original vacancy. of Montgomery and State of Pennsylvania. John McBride, jr., at large, late first lieutenant, Thirtieth In Henry C. Connaway, to be postmaster at Berlin, in the county fantry, United States Volunteers (now second lieutenant, Artillery of Worcester and State of Mal'yland. Corps, United States Army), to fill an original vacancy. Harrison S. Kerrick, of Illinois, late captain, Thirtieth Infan try, United States Volunteers (now second lieutenant, Artillery HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. Corps, United States Army), to fill an original vacancy. Frank J. Miller, at large, late first lieutenant, Forty-first Infan FRIDAY, May 23, 1902. try, United States Volunteers (now second lieutenant, Artillery The House met at 12 o'clock m. Prayer by the Chaplain, Rev. Corps, United States Army), to fill an original vacancy. HENRY N. COUDEN, D. D. Charles L. Lanham, at large, late first lieutenant, Forty-seventh The Journal of the proceedings of yestel'day was read and ap Infantry, United States Volunteers (now second lieutenant, Artil proved. -

Basic Branches of the United States Army Basic Branch Information After

Basic Branches of the United States Army Basic Branch Information After graduation from ROTC Advanced Camp and before commissioning, cadets make the most important decision of their emerging Army career which branch to serve in. The reasons for choosing a branch are varied and personal. The choice can based on the desire to use the academic credentials gained while at school or simply a desire to do something exciting. The 16 basic branches available to cadets are all important to the total Army force and each cannot function without the other. Adjutant General To plan, develop, and direct systems for managing the Army's personnel, administrative, and Army band systems. These systems impact on unit readiness, morale, and soldier career satisfaction, and cover the life cycle management of all Army personnel. Air Defense Artillery The primary mission will be to protect the force and critical tactical and geopolitical assets. This important task is made especially challenging by the evolution of modern tactical ballistic missiles, unmanned aerial vehicles and aircraft. Armor/Cavalry The heritage and spirit of the United States Calvary lives today in Armor. And although the horse has been replaced by 60 tons of steel driven by 1,500HP engine, the dash and daring of the Horse Calvary still reside in Armor. Today, the Armor branch of the Army (which includes Armored Calvary), is one of the Army's most versatile combat arms. It’s continually evolving to meet worldwide challenges and potential threats. Aviation One of the most exciting and capable elements of the Combined Arms Team. As the only branch of the Army that operates in the third dimension of the battlefield, Aviation plays a key role by performing a wide range of missions under diverse conditions. -

Garrison Life of the Mounted Soldier on the Great Plains

/7c GARRISON LIFE OF THE MOUNTED SOLDIER ON THE GREAT PLAINS, TEXAS, AND NEW MEXICO FRONTIERS, 1833-1861 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Stanley S. Graham, B. A. Denton, Texas August, 1969 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page MAPS ..................... .... iv Chapter I. THE REGIMENTS AND THE POSTS . .. 1 II. RECRUITMENT........... ........ 18 III. ROUTINE AT THE WESTERN POSTS ..0. 40 IV. RATIONS, CLOTHING, PROMOTIONS, PAY, AND CARE OF THE DISABLED...... .0.0.0.* 61 V. DISCIPLINE AND RELATED PROBLEMS .. 0 86 VI. ENTERTAINMENT, MORAL GUIDANCE, AND BURIAL OF THE FRONTIER..... 0. 0 . 0 .0 . 0. 109 VII. CONCLUSION.............. ...... 123 BIBLIOGRAPHY.......... .............. ....... ........ 126 iii LIST OF MAPS Figure Page 1. Forts West of the Mississippi in 1830 . .. ........ 15 2. Great Plains Troop Locations, 1837....... ............ 19 3. Great Plains, Texas, and New Mexico Troop Locations, 1848-1860............. ............. 20 4. Water Route to the West .......................... 37 iv CHAPTER I THE REGIMENTS AND THE POSTS The American cavalry, with a rich heritage of peacekeeping and combat action, depending upon the particular need in time, served the nation well as the most mobile armed force until the innovation of air power. In over a century of performance, the army branch adjusted to changing times and new technological advances from single-shot to multiple-shot hand weapons for a person on horseback, to rapid-fire rifles, and eventually to an even more mobile horseless, motor-mounted force. After that change, some Americans still longed for at least one regiment to be remounted on horses, as General John Knowles Herr, the last chief of cavalry in the United States Army, appealed in 1953. -

Fighting Vehicle Technology

Fighting Vehicle Technology 41496_DSTA 60-77#150Q.indd 1 5/6/10 12:44 AM ABSTRACT Armoured vehicle technology has evolved ever since the first tanks appeared in World War One. The traditional Armoured Fighting Vehicle (AFV) design focuses on lethality, survivability and mobility. However, with the growing reliance on communications and command (C2) systems, there is an increased need for the AFV design to be integrated with the vehicle electronics, or vetronics. Vetronics has become a key component of the AFV’s effectiveness on the battlefield. An overview of the technology advances in these areas will be explored. In addition, the impact on the human aspect as a result of these C2 considerations will be covered. Tan Chuan-Yean Mok Shao Hong Vince Yew 41496_DSTA 60-77#150Q.indd 2 5/6/10 12:44 AM Fighting Vehicle Technology 62 and more advanced sub-systems will raise the INTRODUCTION question of how the modern crew is able to process and use the information effectively. On the modern battlefield, armies are moving towards Network-Centric Warfare TECHNOLOGIES IN AN (NCW). Forces no longer fight as individual entities but as part of a larger system. Each AFV entity becomes a node in a network where information can be shared, and firepower can Firepower be called upon request. AFVs are usually equipped with weapon Key to this network fighting capability is the stations for self-protection and the communications and command (C2) system. engagement of targets. Depending on By enabling each force to be plugged into the threat, some are equipped with pintle the C2 system, information can be shared mount systems for light weapons (e.g. -

This Index Lists the Army Units for Which Records Are Available at the Eisenhower Library

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY ABILENE, KANSAS U.S. ARMY: Unit Records, 1917-1950 Linear feet: 687 Approximate number of pages: 1,300,000 The U.S. Army Unit Records collection (formerly: U.S. Army, U.S. Forces, European Theater: Selected After Action Reports, 1941-45) primarily spans the period from 1917 to 1950, with the bulk of the material covering the World War II years (1942-45). The collection is comprised of organizational and operational records and miscellaneous historical material from the files of army units that served in World War II. The collection was originally in the custody of the World War II Records Division (now the Modern Military Records Branch), National Archives and Records Service. The material was withdrawn from their holdings in 1960 and sent to the Kansas City Federal Records Center for shipment to the Eisenhower Library. The records were received by the Library from the Kansas City Records Center on June 1, 1962. Most of the collection contained formerly classified material that was bulk-declassified on June 29, 1973, under declassification project number 735035. General restrictions on the use of records in the National Archives still apply. The collection consists primarily of material from infantry, airborne, cavalry, armor, artillery, engineer, and tank destroyer units; roughly half of the collection consists of material from infantry units, division through company levels. Although the collection contains material from over 2,000 units, with each unit forming a separate series, every army unit that served in World War II is not represented. Approximately seventy-five percent of the documents are from units in the European Theater of Operations, about twenty percent from the Pacific theater, and about five percent from units that served in the western hemisphere during World War II.