Baer on Pepetela, 'Yaka'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Following Is Most of the Text of the Presentation I Did at Readercon 29

The following is most of the text of the presentation I did at Readercon 29. I ran out of time, so I wasn't able to give the entire talk. And my Powerpoint file became corrupted, so I gave the presentation without the images, as I'd originally planned. Here, then, is the original, as requested by a couple of the folks who attended the presentation. THE HISTORY OF HORROR LITERATURE IN AFRICA IN THE 20TH CENTURY Horror literature has not been restricted to the United States, the United Kingdom, and Europe, despite what critics and historians of the genre assume. Most countries which have a flourishing market for popular literature have seen natively-written horror fiction, whether in the form of dime novels, short stories, or novels. This is true of the European countries, whose horror writers are given at least a cursory mention in the broader types of horror criticism. But this is also true of countries outside of Europe, and in countries and continents where Western horror critics dare not tread, like Africa. Now, a thorough history of African horror literature is beyond the time I have today, so what follows is going to be a more limited coverage, of African horror literature in the twentieth century. I’ll be going alphabetically and chronologically through three time periods: 1901-1940, 1941-1970, and 1971-2000. I’d love to be able to tell you a unified theory of African horror literature for those time periods, but there isn’t one. Africa is far too large for that. -

Portuguese Language in Angola: Luso-Creoles' Missing Link? John M

Portuguese language in Angola: luso-creoles' missing link? John M. Lipski {presented at annual meeting of the AATSP, San Diego, August 9, 1995} 0. Introduction Portuguese explorers first reached the Congo Basin in the late 15th century, beginning a linguistic and cultural presence that in some regions was to last for 500 years. In other areas of Africa, Portuguese-based creoles rapidly developed, while for several centuries pidginized Portuguese was a major lingua franca for the Atlantic slave trade, and has been implicated in the formation of many Afro- American creoles. The original Portuguese presence in southwestern Africa was confined to limited missionary activity, and to slave trading in coastal depots, but in the late 19th century, Portugal reentered the Congo-Angola region as a colonial power, committed to establishing permanent European settlements in Africa, and to Europeanizing the native African population. In the intervening centuries, Angola and the Portuguese Congo were the source of thousands of slaves sent to the Americas, whose language and culture profoundly influenced Latin American varieties of Portuguese and Spanish. Despite the key position of the Congo-Angola region for Ibero-American linguistic development, little is known of the continuing use of the Portuguese language by Africans in Congo-Angola during most of the five centuries in question. Only in recent years has some attention been directed to the Portuguese language spoken non-natively but extensively in Angola and Mozambique (Gonçalves 1983). In Angola, the urban second-language varieties of Portuguese, especially as spoken in the squatter communities of Luanda, have been referred to as Musseque Portuguese, a name derived from the KiMbundu term used to designate the shantytowns themselves. -

On Literature and National Culture

ON LITERATU RE AND NAT IONAL CULTURE1 By Agostinho Neto 0 O.V LITERATURg2 COmrades: It is with the greatest pleasure that I attend this formal ceremony for the installation of the Governing Bodies of the Angolan Writers' Union. As all of you will understand, only the guarantees offered by the other members of the General Assembly and by the COmrade Secretary- General were able to convince me to accept one more obligation added to so many others. Nevertheless, I wish to thank the Angolan Writers ' Union for this kind gesture and to express my hope that whenever it may be necessary for me to make my contribution to the Union that the COmrades as a whole or individually will not hesitate to put before me the problems that go along with these new duties that I now assume . I wish to use this occasion to pay homage to those COmrade writers who before and after the national liberation struggle suffered persecution, to those who lost their freedom in prison or exile, and to those who inside the country were politically segr~gated and thus placed in unusual situations. I also wish to join with all the COmrades here in the homage that was paid to those Comrades who heroically made the ultimate sacrifice during the national liberation struggle, and who today are no longer with us. Comrades: We have taken one more step forward in our national life with the forming of this Writers' Union which continues the literary traditions of the period of resistence against colon ialism. During that period, and in spite of colonial-fascist repression, a task was accomplished that will go down in the annals of Angola' s revolutionary history as a valuable contri bution to the Victory of the Angolan People. -

Tell Me Still, Angola the False Thing That Is Dystopia

https://doi.org/10.22409/gragoata.v26i55.47864 Tell me Still, Angola the False Thing that is Dystopia Solange Evangelista Luis a ABSTRACT José Luis Mendonça’s book Angola, me diz ainda (2017) brings together poems from the 1980s to 2016, unveiling a constellation of images that express the unfulfilled utopian Angolan dream. Although his poems gravitate around his personal experiences, they reflect a collective past. They can be understood as what Walter Benjamin called monads: historical objects (BENJAMIN, 2006, p. 262) based on the poet’s own experiences, full of meaning, emotions, feelings, and dreams. Through these monadic poems, his poetry establishes a dialogue with the past. The poet’s dystopic present is that of an Angola distanced from the dream manifested in the insubmissive poetry of Agostinho Neto and of the Message Generation, which incited decolonization through a liberation struggle and projected a utopian new nation. Mendonça revisits Neto’s Message Generation and its appeal to discover Angola: unveiling a nation with a broken dream and a dystopic present, denouncing a future that is still to come. The poet’s monads do not dwell on dystopia but wrestle conformism, fanning the spark of hope (BENJAMIN, 2006, p. 391). They expose what Adorno named the false thing (BLOCH, 1996, p. 12), sparking the longing for something true: reminding the reader that transformation is inevitable. Keywords: Angolan Literature. José Luís Mendonça. Lusophone African Literature. Dystopia. Walter Benjamin. Recebido em: 29/12/2020 Aceito em: 27/01/2021 a Universidade do Porto, Centro de Estudos Africanos, Porto, Portugal E-mail: [email protected] How to cite: LUIS, S.E. -

Angola, a Nation in Pieces in José Eduardo Agualusa's Estação Das

Angola, a Nation in Pieces in José Eduardo Agualusa’s Estação das chuvas RAQUEL RIBEIRO University of Edinburgh Abstract: In this article, I examine José Eduardo Agualusa’s Estação das chuvas (1996), as a novel that lays bare the contradictions of the MPLA’s revolutionary process after Angola’s independence. I begin with a discussion of the proximity between trauma and (the impossibility) of fiction. I then consider the challenges Angolan writers face in presenting an alternative discourse to the “one-party, one-people, one-nation” narrative propagated by the MPLA). Finally, I discuss how Estação das chuvas, which complicates both truth/verisimilitud and history/fiction, presents an alternative vision of Angola’s national narrative. Keywords: Angolan literature; MPLA; UNITA; Truth and fiction; Nation The Angolan civil war broke out in 1975 and lasted 27 years. Yet there are still very few literary accounts of the conflict by Angolan writers. Novels about the civil war have been scarce, and there are few first person or testimonial records by those who participated directly in the conflict, as victims or perpetrators. The war was an enduring presence in Angolan literature in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, but always as something distant. Generally, books do not explicitly evoke the conflict, international military interventions (South African, Soviet, Cuban), its conscripts, prisoners, and atrocities perpetrated by both the MPLA and UNITA. Texts that dealt with it at the time left its contradictions and ideological complexities aside, focusing instead on how it forced millions to migrate to 57 Ribeiro Luanda, its consequences for families, and the hardships of daily life for certain classes of Angolans. -

A HISTORY of TWENTIETH CENTURY AFRICAN LITERATURE.Rtf

A HISTORY OF TWENTIETH CENTURY AFRICAN LITERATURES Edited by Oyekan Owomoyela UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA PRESS © 1993 by the University of Nebraska Press All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America The paper in this book meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI 239.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A History of twentieth-century African literatures / edited by Oyekan Owomoyela. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8032-3552-6 (alk. paper) — ISBN 0-8032-8604-x (pbk.: alk. paper) I. Owomoyela, Oyekan. PL80I0.H57 1993 809'8896—dc20 92-37874 CIP To the memory of John F. Povey Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction I CHAPTER I English-Language Fiction from West Africa 9 Jonathan A. Peters CHAPTER 2 English-Language Fiction from East Africa 49 Arlene A. Elder CHAPTER 3 English-Language Fiction from South Africa 85 John F. Povey CHAPTER 4 English-Language Poetry 105 Thomas Knipp CHAPTER 5 English-Language Drama and Theater 138 J. Ndukaku Amankulor CHAPTER 6 French-Language Fiction 173 Servanne Woodward CHAPTER 7 French-Language Poetry 198 Edris Makward CHAPTER 8 French-Language Drama and Theater 227 Alain Ricard CHAPTER 9 Portuguese-Language Literature 240 Russell G. Hamilton -vii- CHAPTER 10 African-Language Literatures: Perspectives on Culture and Identity 285 Robert Cancel CHAPTER II African Women Writers: Toward a Literary History 311 Carole Boyce Davies and Elaine Savory Fido CHAPTER 12 The Question of Language in African Literatures 347 Oyekan Owomoyela CHAPTER 13 Publishing in Africa: The Crisis and the Challenge 369 Hans M. -

Examining Angolan Fiction

Phyllis Peres, Inc. NetLibrary. Transculturation and resistance in Lusophone African narrative. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1997. x + 131 pp. ISBN 978-0-8130-2368-7. Reviewed by Elizabeth Blakesley Lindsay Published on H-AfrLitCine (February, 1998) Although Phyllis Peres doesn't mention it, this es the post-independence works of Rui and the work is an update of National Literary Identity in continued efforts to define nation in the post-colo‐ Contemporary Angolan Prose Fiction, the fne dis‐ nial era. sertation she wrote at the University of Minnesota Throughout, Peres offers strong evidence (1986) as Phyllis A. Reisman. from the text for her thesis, and provides insight‐ Peres begins by examining the history and ful analysis of those textual examples. Peres has context of Angolan writing, noting the importance been able to meet and consult with all four of the of events from early colonial history and the as‐ authors she studies, a fact which greatly enriches similation policies of the Portuguese to Lusotropi‐ her insights into a number of works and issues. calismo and the Generation of 1950. All this leads Peres concludes by reminding us that Angolan Peres to defining transculturation, an anthropo‐ writing is different than other post-colonial logical concept she has adopted as a theoretical African writing, pointing to Angola's prolonged framework for examining the process and prod‐ fight for independence and the brutal civil war, uct of Angolan literature. Transculturation marks which has comprised most of its post-colonial a movement toward a national culture or a na‐ years. Peres states that "for all the common tional literary identity and works as a means of ground that one can fnd in post-colonial African resisting colonial acculturation. -

Remembering Angola

The Creole Elite and the Rise of Angolan Proto-Nationalism: 1880-1910 Jacopo Corrado Abstract: The main purpose of this essay is to define the peculiarities of Angolan urban society and trace its evolution during the second half of the nineteenth century, a lapse of time marked by relative freedom—due to the economic crisis affecting Portugal from the definitive abolition of slavery and to the social and artistic progressive reformer impulse pro- moted by the Generation of 1870. This made possible the establishment in Luanda of lively journalistic activity and the production of a literary corpus—principally written by traders, soldiers, public officers, and landowners, born in Africa and tied both to their European and African origins, which witnessed the growth of a feeling of dissatisfaction destined to culminate in a heterogeneous set of open claims for autonomy or even independence. This article investigates a segment of Angolan history and literature with which non-Portuguese-speaking readers are generally not familiar, for its main purpose is to define the features and the literary production of what are conventionally called Creole elites, whose contribution to the early manifes- tations of dissatisfaction towards colonial rule was patent between 1880 and 1910, a period of renewed Portuguese commitment to its African colonies, but also of unrealised ambitions, economic crisis and socio-political upheaval in Angola and in Portugal itself. At that time, Angolan society was characterized by the presence of a semi- Portuguese Literary & Cultural Studies 15/16 (2010): 57-77. © University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. 58 PORTUGUESE LITERARY & CULTURAL STUDIES 15/16 urbanized commercial and administrative elite of Portuguese-speaking Creole families—white, black, some of mixed race, some Catholic and others Protestant, some old-established and others cosmopolitan—who were based in the main coastal towns. -

LCSH Section Y

Y-Bj dialects Yabakei (Japan) Yacatas Site (Mexico) USE Yugambeh-Bundjalung dialects BT Valleys—Japan BT Mexico—Antiquities Y-cars Yabakei (Japan) Yaccas USE General Motors Y-cars USE Yaba Valley (Japan) USE Xanthorrhoea Y chromosome Yabarana Indians (May Subd Geog) Yachats River (Or.) UF Chromosome Y UF Yaurana Indians BT Rivers—Oregon BT Sex chromosomes BT Indians of South America—Venezuela Yachats River Valley (Or.) — Abnormalities (May Subd Geog) Yabbie culture UF Yachats Valley (Or.) BT Sex chromosome abnormalities USE Yabby culture BT Valleys—Oregon Y Fenai (Wales) Yabbies (May Subd Geog) Yachats Valley (Or.) USE Menai Strait (Wales) [QL444.M33 (Zoology)] USE Yachats River Valley (Or.) Y-G personality test BT Cherax Yachikadai Iseki (Haga-machi, Tochigi-ken, Japan) USE Yatabe-Guilford personality test Yabby culture (May Subd Geog) USE Yachikadai Site (Haga-machi, Tochigi-ken, Y.M.C.A. libraries [SH380.94.Y32] Japan) USE Young Men's Christian Association libraries UF Yabbie culture Yachikadai Site (Haga-machi, Tochigi-ken, Japan) Y maze Yabby farming This heading is not valid for use as a geographic BT Maze tests BT Crayfish culture subdivision. Y Mountain (Utah) Yabby farming UF Yachikadai Iseki (Haga-machi, Tochigi-ken, BT Mountains—Utah USE Yabby culture Japan) Wasatch Range (Utah and Idaho) YABC (Behavioral assessment) BT Japan—Antiquities Y-particles USE Young Adult Behavior Checklist Yachinaka Tate Iseki (Hinai-machi, Japan) USE Hyperons Yabe family (Not Subd Geog) USE Yachinaka Tate Site (Hinai-machi, Japan) Y-platform cars Yabem (Papua New Guinean people) Yachinaka Tate Site (Hinai-machi, Japan) USE General Motors Y-cars USE Yabim (Papua New Guinean people) This heading is not valid for use as a geographic subdivision. -

A History of Angola

Dickinson College Dickinson Scholar Faculty and Staff Publications By Year Faculty and Staff Publications 11-2017 A History of Angola Jeremy R. Ball Dickinson College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.dickinson.edu/faculty_publications Part of the African History Commons Recommended Citation Ball, Jeremy. "The History of Angola." In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. (Article published online November 2017). http://africanhistory.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/ 9780190277734.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277734-e-180 This article is brought to you for free and open access by Dickinson Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The History of Angola Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History The History of Angola Jeremy Ball Subject: Central Africa, Colonial Conquest and Rule Online Publication Date: Nov 2017 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.180 Summary and Keywords Angola’s contemporary political boundaries resulted from 20th-century colonialism. The roots of Angola, however, reach far into the past. When Portuguese caravels arrived in the Congo River estuary in the late 15th century, independent African polities dotted this vast region. Some people lived in populous, hierarchical states such as the Kingdom of Kongo, but most lived in smaller political entities centered on lineage-village settlements. The Portuguese colony of Angola grew out of a settlement established at Luanda Bay in 1576. From its inception, Portuguese Angola existed to profit from the transatlantic slave trade, which became the colony’s economic foundation for the next three centuries. A Luso- African population and a creole culture developed in the colonial nuclei of Luanda and Benguela (founded 1617). -

ECFG-Angola-2020R.Pdf

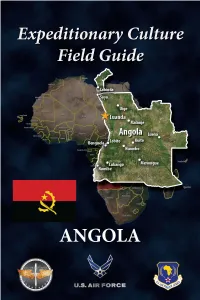

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success. ECFG The guide consists of 2 parts: Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Angola Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” Angola, focusing on unique cultural features of Angolan society and is designed to complement other pre-deployment training. It applies culture- general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. All human beings have culture, and individuals within a culture share a general set of beliefs and values. -

Angola After 40 Years of Independence: the Way Ahead

Africa Conference Meeting Summary Angola after 40 Years of Independence: The Way Ahead 12 November 2015 The views expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the speaker(s) and participants, and do not necessarily reflect the view of Chatham House, its staff, associates or Council. Chatham House is independent and owes no allegiance to any government or to any political body. It does not take institutional positions on policy issues. This document is issued on the understanding that if any extract is used, the author(s)/speaker(s) and Chatham House should be credited, preferably with the date of the publication or details of the event. Where this document refers to or reports statements made by speakers at an event, every effort has been made to provide a fair representation of their views and opinions. The published text of speeches and presentations may differ from delivery. © The Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2016. 10 St James’s Square, London SW1Y 4LE T +44 (0)20 7957 5700 F +44 (0)20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org Patron: Her Majesty The Queen Chairman: Stuart Popham QC Director: Dr Robin Niblett Charity Registration Number: 208223 2 Angola after 40 Years of Independence: The Way Ahead Introduction On 12 November 2015, Chatham House’s Africa Programme hosted a conference to mark the 40th anniversary of Angola’s independence. Since the 2002 Luena Memorandum of Understanding that ended one of the continent’s longest civil wars, Angola has enjoyed a prolonged period of extractives-driven growth. But the new realities of low commodity prices and depleting oil resources are creating pressure for economic diversification.