Next Year in Jerusalem: a Brief History of Hope

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rome International Conference on the Responsibility of States, Institutions and Individuals in the Fight Against Anti-Semitism in the OSCE Area

Rome International Conference on the Responsibility of States, Institutions and Individuals in the Fight against Anti-Semitism in the OSCE Area Rome, Italy, 29 January 2018 PROGRAMME Monday, 29 January 10.00 - 10.30 Registration of participants and welcome coffee 10.45 - 13.30 Plenary session, International Conference Hall 10.45 - 11.30 Opening remarks: - H.E. Angelino Alfano, Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, OSCE Chairperson-in-Office - H.E. Ambassador Thomas Greminger, OSCE Secretary General - H. E. Ingibjörg Sólrún Gísladóttir, ODIHR Director - Ronald Lauder, President, World Jewish Congress - Moshe Kantor, President, European Jewish Congress - Noemi Di Segni, President, Union of the Italian Jewish Communities 11.30 – 13.00 Interventions by Ministers 13.00 - 13.30 The Meaning of Responsibility: - Rabbi Israel Meir Lau, Chairman of Yad Vashem Council - Daniel S. Mariaschin, CEO B’nai Brith - Prof. Andrea Riccardi, Founder of the Community of Sant’Egidio 13.30 - 14.15 Lunch break - 2 - 14.15 - 16.15 Panel 1, International Conference Hall “Responsibility: the role of law makers and civil servants” Moderator: Maurizio Molinari, Editor in Chief of the daily La Stampa Panel Speakers: - David Harris’s Video Message, CEO American Jewish Committee - Cristina Finch, Head of Department for Tolerance and Non- discrimination, ODHIR - Katharina von Schnurbein, Special Coordinator of EU Commission on Anti-Semitism - Franco Gabrielli, Chief of Italian Police - Ruth Dureghello, President of Rome Jewish Community - Sandro De -

Italian Jewish Subjectivities and the Jewish Museum of Rome

What is an Italian Jew? Italian Jewish Subjectivities and the Jewish Museum of Rome 1. Introduction The Roman Jewish ghetto is no more. Standing in its place is the Tempio Maggiore, or Great Synagogue, a monumental testament to the emancipation of Roman and Italian Jewry in the late nineteenth century. During that era, the Roman Jewish community, along with city planners, raised most of the old ghetto environs to make way for a less crowded, more hygienic, and overtly modern Jewish quarter.1 Today only one piece of the ghetto wall remains, and the Comunità Ebraica di Roma has dwindled to approximately 15,000 Jews. The ghetto area is home to shops and restaurants that serve a diverse tourist clientele. The Museo Ebraico di Roma, housed, along with the Spanish synagogue, in the basement floor of the Great Synagogue, showcases, with artifacts and art, the long history of Roman Jewry. While visiting, one also notices the video cameras, heavier police presence, and use of security protocol at sites, all of which suggest very real threats to the community and its public spaces. This essay explores how Rome's Jewish Museum and synagogues complex represent Italian Jewish identity. It uses the complex and its guidebook to investigate how the museum displays multiple, complex, and even contradictory subject-effects. These effects are complicated by the non- homogeneity of the audience the museum seeks to address, an audience that includes both Jews and non-Jews. What can this space and its history tell us about how this particular “contact zone” seeks to actualize subjects? How can attention to these matters stimulate a richer, more complex understanding of Italian Jewish subjectivities and their histories? We will ultimately suggest that, as a result of history, the museum is on some level “caught” between a series of contradictions, wanting on the one hand to demonstrate the Comunità Ebraica di Roma’s twentieth-century commitment to Zionism and on the other to be true to the historical legacy of its millennial-long diasporic origins. -

The World Bank, the IMF and the Global Prevention of Terrorism: a Role for Conditionalities, 29 Brook

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Brooklyn Law School: BrooklynWorks Brooklyn Journal of International Law Volume 29 | Issue 2 Article 3 2004 The orW ld Bank, The IMF nda the Global Prevention of Terrorism: A Role for Conditionalities Olivera Medenica Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil Recommended Citation Olivera Medenica, The World Bank, The IMF and the Global Prevention of Terrorism: A Role for Conditionalities, 29 Brook. J. Int'l L. (2004). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil/vol29/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. File: Olivera3.22.macro.doc Created on: 3/22/2004 2:32 PM Last Printed: 3/29/2004 11:40 AM THE WORLD BANK, THE IMF AND THE GLOBAL PREVENTION OF TERRORISM: A ROLE FOR CONDITIONALITIES Olivera Medenica* I. INTRODUCTION he Twin Towers, an architectural symbol of Western Tpower, came crashing down on a beautiful and hopelessly tragic September morning. The incredible scale of the attack left us horrified, bewildered, and wounded as a nation. With ghastly images in our memory, the U.S. turned towards the bleak prospect of fighting an elusive enemy. Like any true eco- nomic and military superpower, our response was strong and immediate. But was our response efficient, and most impor- tantly, are we safer now than before? In an interview granted shortly after September 11, 2001, James Wolfhenson, the president of the World Bank, described the collapse of the Twin Towers as not only a terrorist attack of the grandest scale, but also as the image “of the South landing hard on the cradle of the North.”1 This statement is insightful because it is powerfully descriptive and suggests that a collec- tive response is needed to address the issue. -

Award Winner Award Winner

AwardAward Volume XVIII, No. 2 • New York City • NOV/DEC 2012 www.EDUCATIONUPDATE.com Winner CUTTING EDGE NEWS FOR ALL THE PEOPLE UPDATE THE EDUCATION THE PAID U.S. POSTAGE U.S. PRESORTED STANDARD PRESORTED 2 EDUCATION UPDATE ■ FPOR ARENTS, Educators & Students ■ NOV/DEC 2012 GUEST EDITORIAL EDUCATION UPDATE MAILING ADDRESS: Achieving Student Success in Community Colleges 695 Park Avenue, Ste. E1509, NY, NY 10065 Email: [email protected] www.EducationUpdate.com By JAY HERSHENSON Programs (ASAP) and 25 students. Tel: 212-650-3552 Fax: 212-410-0591 n today’s highly competitive global the New Community Students in the first cohort were required to PUBLISHERS: economy, community college stu- College at CUNY. overcome any developmental needs in the sum- Pola Rosen, Ed.D., Adam Sugerman, M.A. dents must earn valued degrees We all know how mer before admission, and about a third did so. ADVISORY COUNCIL: as quickly and assuredly as possi- few urban community So when they were ready to start credit-bearing Mary Brabeck, Dean, NYU Steinhardt School of Culture, Ed., and Human Dev.; Christine Cea, ble. Through academic advisement and finan- college students earn courses, they were all up to speed. Ph.D., NYS Board of Regents; Shelia Evans- cial aid support, block class and summer bridge a degree within three There was regular contact with faculty and Tranumn, Chair, Board of Trustees, Casey Family programs, and greater emphasis on study skills, years — in some parts advisors. Students who needed jobs, job skills Programs Foundation; Charlotte K. Frank, we can better assist incoming freshmen to of the country 16 per- and career planning were helped. -

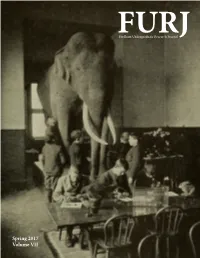

Spring 2017 Volume VII

FURJFordham Undergraduate Research Journal Spring 2017 Volume VII FURJThe Fordham Undergraduate Research Journal Spring 2017 Volume VII Table of Contents News Fordham Alumna Feature: Mary Jane McCartney 6 Carolyn Allain Algorithmic Randomness: A Work of Passion 7 Brian Collins Discovering Lepidoptera Diversity in New York City 8 Anders T. Papritz Structured Intervention for Inner-City Youth Exposed to Complex Trauma 9 Maria Julia Pieraccioni Research Articles Economic Sanctions: Comparing South Africa and Iraq 11 Corina Minden-Birkenmaier Undocumented Minors and Their Obstacles to Public Education: 15 A Case Study of New York Public Education from 2014–2015 Alexa Tovar Rebellion in Print Luca Vettori 17 Smartwatch Based Transcription Biometrics 22 Francesco Ciuffo The Effeminate and Subversive Jewish Male Body 26 Dean Michael Fryn Kouroi: From Ancient Tradition to American Identity 30 Francesa Aton “Savage, Hero, or Whore?” How Linguistic Choice Prevents HIV Alexander Partridge 38 Book Reviews Before the Fires 44 Shannon Kelsh 45 Using Technology, Building Democracy: Digital Campaigning and the Construction of Citizenship Stephanie Galbraith Cover: Excerpt from page 105 of What To Do For Uncle Sam written by Carolyn Sherwin Bailey (1918) 3 A Letter from the Editor Dear Fordham Community, Alongside a tireless Editorial Board and General Staff, I am pleased to present The Fordham Undergraduate Research Journal, Volume VII. Like FURJ leaders and staff, Fordham’s undergraduate researchers color the innovation and collaboration occurring on our campus daily. In this issue, discover how smartwatches can be incorporated into security protocol, how perceptions of Jewish masculinity once promulgated crime, how elephants symbolize hierarchies in literature, and much more. -

CI HANNO DIVISI (We Have Been Separated) ICS EVENTS COMING SOON

MARCELLO GALATI - Italian writer and journalist. He began writing for the stage while still employed as a radio reporter at Radio Popolare di Milano. His first play, staged in 2013, was a farce about the affairs of the Ilva steelworks in Taranto. His love and deep knowledge of jazz music has been the muse of “Sospendete l’incredulità”, an interesting collage of stories about the great jazz musicians. Last summer his monologue "Tre amori" was interpreted by Tiziana Risolo at the University of Taranto. MAURIZIO COLONNA Among the most representative and eclectic guitarists-composers of today, born in Turin in 1959, he started playing the guitar at five years old, at seven he made his debut in theater as a soloist, and at seventeen he played the Concierto de Aranjuez for guitar and orchestra, in the presence of J. Rodrigo. He has written numerous compositions for guitar, for two guitars, film music, In collaboration with US-Italy Global Affairs music for guitar and piano, written together with the pianist-composer Luciana Bigazzi and historical-musical books. and Georgetown University Department of Italian HEARSTRINGS DUO Tiziana Risolo and Felicia Toscano formed the Heartstrings Duo, and met in Washington DC in 2018, and they both come from the same city in Italy, Taranto. Tiziana is an actress, who played leading roles in some of the main theatrical performances across Italy. Felicia is a renowned guitarist and presents conductor. On stage, the duo Heartstrings performed an extract of 'Eva and the Verb' by Carlo Terron during The International Women's Day organized by Le D.I.V.E. -

The Jewish Center

The Jewish Center SHABBAT BULLETIN JUNE 17, 2017 • P ARSHAT SHELACH • 23 S IVAN 5777 EREV SHABBAT GRADUATION KIDDUSH 7:00/8:00PM Minchah SHABBAT JUNE 17 8:11PM Candle lighting Join us as we celebrate the SHABBAT academic achievements of our 7:45AM Hashkama Minyan (The Max and Marion community graduates. Grill Beit Midrash) See insert for complete list of 8:30AM Kids’ Kiddush club with Rabbi Yosie Levine sponsors and graduates. (1st Floor) 9:00AM Shacharit (3rd floor) 9:10AM Sof Zman Kriat Shema Annual Membership Meeting 9:15AM Hashkama Shiur, Rabbi Avi Feder, Hi, What's June 19 at 8:30PM your name? Changing or adding a name to affect healing Our Annual Meeting is a time to hold our annual elec- 9:30AM Young Leadership Minyan (1st floor) tion, learn more about the way we operate our Cen- ter, review our finances and honor our outgoing Board 10:00AM Youth Groups: Under age 3 (drop off option- members. This meeting is an important part of syna- al, babies must be able to independently sit upright), gogue governance and I hope you will be able to 3-6-year-olds: Geller Youth Center, 2nd-6th attend so you can listen to our reports, ask questions graders: 7th floor and grab a little nosh. Hot Kiddush (1st & 5th floor) WITH THANKS TO OUR KIDDUSH SPONSORS: Summer Outing with Rabbi Levine Hashkama Kiddush, Renee & Avram Schreiber in honor June 22, 11:00AM at the YU Museum of the graduation of their grandson, Elan Agus from A guided tour of 500 Years of Treasures from Oxford Ramaz middle school $10 members; $12 non-members Community Kiddush, Amy & Jed Latkin in honor of the Please email [email protected] if you would 30th anniversary of Jed's bar mitzvah. -

A Century of Italian American Economics

A Century of Italian American Economics A Century of Italian American Economics: The American Chamber of Commerce in Italy (1915-2015) By Valentina Sgro A Century of Italian American Economics: The American Chamber of Commerce in Italy (1915-2015) By Valentina Sgro This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Valentina Sgro All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-5369-8 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-5369-9 CONTENTS List of Tables ............................................................................................ vii List of Figures............................................................................................ ix Foreword ................................................................................................... xi People and Companies in the U.S. Economy of the 20th Century: An Overview Vittoria Ferrandino Acknowledgements ................................................................................ xxv Chapter One ................................................................................................ 1 The Founding of the American Chamber of Commerce in -

Yearbook Keren Hayesod 2017

YEARBOOK KEREN HAYESOD 2017 SII FIERO DEL TUO PASSATO PRENDI PARTE AL TUO FUTURO AIUTA ISRAELE PER AIUTARE TE STESSO LA NOSTRA MISSIONE Il Keren Hayesod, istituzione nazionale dello Stato d’Israele, rappresenta da quasi 100 anni il principale braccio operativo di raccolta fondi del Movimento Sionista e dell’Agenzia Ebraica, facendosi ponte vivente fra milioni di ebrei della Diaspora e lo Stato d’Israele. Israele: dallo spazio una macchia verde in un mare di sabbia. Quanto lavoro per ottenere questo miracolo. Oggi il paese risulta ai primi posti in tutte le classifiche mondiali. Non per dimensioni, non per popolazione, ma, nonostante guerre e terrorismo, per istruzione, qualità della vita, innovazione tecnologica, libertà, diritti umani, democrazia e ... felicità! Il Keren Hayesod è orgoglioso di aver contribuito a questi risultati grazie a tutti voi. 2 marzo 2017 Hotel Melià, Milano BENVENUTI Grazie, parola forse abusata in eventi di raccolta fondi, ma davvero sentita in questa occasione perché chi è qui stasera ha in comune con tutti gli altri l'amore per Israele. Ci sono qui ebrei, per cui questo amore è connaturato, ma anche tanti non ebrei, per cui Israele rappresenta la libertà e la giustizia in un mondo di sopraffazione. Siete qui questa sera per portare a Israele la vostra solidarietà, e questo ci sarebbe bastato! Ma siete qui anche per dare un aiuto concreto con una donazione di qualsiasi entità al popolo di Israele che, nonostante la crescita economica, ha sempre grandi Andrea Jarach necessità per accogliere i profughi, eliminare le disparità sociali, Presidente nazionale arginare le continue emergenze. -

On Newspapers in Italy at Present, Most Italian Daily Newspapers with National Circulation Are Run by Men. Nevertheless, We

On newspapers in Italy At present, most Italian daily newspapers with national circulation are run by men. Nevertheless, we can highlight the appointment, in 2019, of Ms Agnese Pini as editor-in-chief of the newspaper 'La Nazione', being the first woman to hold this position in the 160 years of the life of the Florentine newspaper1. Previously, we can point out the naming, in 2010, of Ms Norma Rangeri as editor-in-chief of the left- wing Roman newspaper "Il Manifesto". Other examples in the past, at a lower geographic level, include Ms Pierangela Fiorani as editor-in- chief of Provincia Pavese (daily newspaper of Pavia) from 2006 to 2014 and from 2014 to 2016 of the four Venetian daily newspapers of Gruppo Espresso (now GEDI Gruppo Editoriale)2, as well as Ms Lucia Serino, appointed editor-in-chief of "Il Quotidiano della Basilicata" for 4 years between 2011 and 2015, or Ms Anna Mossutto, who held the same position in “Corriere dell'Umbria” for 10 years after being nominated in 2009. Historically, it is worth mentioning the case of Mrs Matilde Serao, the first Italian woman to found and run a newspaper, “Il Corriere di Roma”, in 1885, an experience she repeated with other newspapers in the following years. The genders of the chief editors among the seven largest Italian newspapers by circulation3 are shown in Table 1 below4: TABLE 1 Average circulation5 Political Publishing Gender editor-in-chief Newspaper (April 2020) alignment group (name) (ADS) Corriere della RCS 256,564 Liberalism Male (Luciano Fontana) Sera MediaGroup GEDI La Repubblica 201,645 Centre-Left Gruppo Male (Maurizio Molinari) Editoriale GEDI Liberalism, La Stampa 150,387 Gruppo Male (Massimo Giannini) centrism Editoriale Poligrafici QN – Il Resto Editoriale 105,397 Conservatism Male (Michele Brambilla) del Carlino (Monrif Group) 1This has been published in newspapers such as “La Repubblica”: “Agnese Pini new editor of ‘La Nazione’ https://firenze.repubblica.it/cronaca/2019/07/30/news/agnese_pini_direttore_la_nazione-232396718/ [Date consulted: July 6th, 2020]. -

WASH YOUR HANDS by Alain Elkann 17 April 2020 It Was a Frenetic

WASH YOUR HANDS by Alain Elkann 17 April 2020 It was a frenetic morning full of telephone calls, catching up with people here and there. When would things open? When would the government send out stimulus payments? You woke up in the morning in one frame of mind but then there was so much uncertainty. Carmen Llera Moravia called, saying she was constantly on the go. She was out and about on the streets of Rome wearing an ever changing array of masks. She told him she’d sold the house in Sabaudia, the one designed by Dante Ferretti that Moravia had shared with Pasolini. She sold it because the caretakers were getting old and she never went there anyway. “You always go to Paris, don’t you?” she asked. “I used to go, but now how could I go anywhere?” “Do you have a house in Paris?” “No. You know I hate having property. I stay at the Hôtel des Saints Pères.” As Carmen spoke, he began to feel nostalgic for his Paris, the Paris of Saint Germain, Café de Flore, Brasserie Lipp, Rue de Grenelle, Rue de Varenne, Rue du Bac, the Hôtel de Saint-Simon, the Chinese restaurant on Boulevard Saint- Germain, the Gallimard bookshop, Boulevard Raspail, the street that led down to Quai Voltaire and those few streets that had been his little village since he was twenty years old. Including Rue de Seine, Rue Jacob, Rue de l’Université, Place Saint-Sulpice, and Rue de Turnon. His mind flashed back to those places, those hotels, those homes, the Luxembourg Gardens. -

Presidential Documents

Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents Monday, July 23, 2001 Volume 37—Number 29 Pages 1043–1075 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 09:04 Jul 25, 2001 Jkt 010199 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 1249 Sfmt 1249 W:\DISC\P29JY4.000 txed02 PsN: txed02 Contents Addresses and Remarks Joint Statements See also Meetings With Foreign Leaders G–7 Statement—1068 Congressional Medal of Honor, presentation to Capt. Ed W. Freeman—1044 Meetings With Foreign Leaders Italy, satellite remarks from Genoa to a tax relief celebration in Kansas City, MO— G–7 leaders—1068 1071 United Kingdom, Prime Minister Blair—1062 Radio address—1043 United Kingdom, departure from Oxford— Statements by the President 1067 Winston Churchill, bust—1045 Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act, World Bank—1048 Title III—1047 Death of Katharine Graham—1051 Communications to Congress House of Representatives action Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Faith-Based and Community Initiative— (LIBERTAD) Act of 1996, letter on review 1061 of Title III—1048 National energy policy, by committees— Sierra Leone, message transmitting report on national emergency—1051 1051 Interviews With the News Media Supplementary Materials Exchanges with reporters Acts approved by the President—1075 London, United Kingdom—1060 Oval Office—1045 Checklist of White House press releases— Interview with foreign journalists—1051 1075 News conference with Prime Minister Blair of Digest of other White House the United Kingdom in Halton, July 19 announcements—1072 (No. 12)—1062 Nominations submitted to the Senate—1073 Editor’s Note: The President was in Genoa, Italy, on July 20, the closing date of this issue. Releases and announcements issued by the Office of the Press Secretary but not received in time for inclusion in this issue will be printed next week.