The Westminster Alice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Book the Westminster Alice : a Political Parody Based on Lewis Carrolls Wonderland

THE WESTMINSTER ALICE : A POLITICAL PARODY BASED ON LEWIS CARROLLS WONDERLAND Author: Hector Hugh Munro (Saki) Number of Pages: 98 pages Published Date: 01 Aug 2010 Publisher: Evertype Publication Country: United Kingdom Language: English ISBN: 9781904808541 DOWNLOAD: THE WESTMINSTER ALICE : A POLITICAL PARODY BASED ON LEWIS CARROLLS WONDERLAND The Westminster Alice : A Political Parody Based on Lewis Carrolls Wonderland PDF Book Starratt's focus on leadership as human resource development will energize the efforts of faculty, staff, and students to improve the quality of learning-the primary work of schools. This will enable me to give more time to the discussion of those methods, the utility of which is still an open question. You'll find yourself basking in God's love while giving it away. No matter what your background is, this book will enable you to master Excel 2016's most advanced features. To this end they have gathered together a distinguished group of economists, sociologists, political scientists, and organization, innovation and institutional theorists to both assess current research on innovation, and to set out a new research agenda. She then traveled to Manhattan to attend Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons. Visit GiftOfLogic. But the policy changes made between 2007 and 2010 will likely constrain any new initiatives in the future. Then,afteratwo-weekelectronic discussion, the Programme Committee selected 33 papers for presentation at the conference. (New Scientist) The book certainly merits its acceptance as essential reading for postgraduates and will be valuable to anyone associated in any way with research or with presentation of technical or scientific information of any kind. -

"Animals in Saki's Short Stories Within the Context of Imperialism: a Non

Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of English Language and Literature ANIMALS IN SAKI’S SHORT STORIES WITHIN THE CONTEXT OF IMPERIALISM: A NON-ANTHROPOCENTRIC APPROACH Adem Balcı Master’s Thesis Ankara, 2014 ANIMALS IN SAKI’S SHORT STORIES WITHIN THE CONTEXT OF IMPERIALISM: A NON-ANTHROPOCENTRIC APPROACH Adem Balcı Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of English Language and Literature Master’s Thesis Ankara, 2014 iii To my family iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to my supervisor Assist. Prof. Dr. Sinan AKILLI for his encouragement, friendship, and academic guidance. Without his never-ending support, encouragement, constructive criticism, unwavering belief in me, unending patience, genuine kindness, suggestions, meticulous feedbacks and comments, this thesis would not be what it is now. I would also like to express my deepest gratitude to Prof. Dr. Burçin EROL, the Head of the Department of English Language and Literature, for her endless support, warm welcome, motivation and encouragement whenever I needed. I wish to express my sincere gratitude to the distinguished members of the Examining Committee who contributed to this thesis through their constructive comments and meticulous feedback. Firstly, I would like to thank Prof. Dr. Deniz BOZER for her suggestions, invaluable comments, and academic guidance in each step of this thesis. I would also like to thank Prof. Dr. Serpil OPPERMANN wholeheartedly for introducing me to the posthumanities and animal studies, for helping me to write my thesis proposal and finally for her contribution to the development of this thesis with her invaluable comments, her books, and feedbacks. -

Cast List- Alice in Wonderland Alice- Rachel M. Mathilda- Chynna A

Cast List- Alice in Wonderland Alice- Rachel M. Mathilda- Chynna A. Cheshire Cat 1- Jelayshia B. Cheshire Cat 2- Skylar B. Cheshire Cat 3- Shikirah H. White Rabbit- Cassie C. Doorknob- Mackenzie L. Dodo Bird- Latasia C. Rock Lobsters & Sea Creatures- Kayla M., Mariscia M., Bar’Shon B., Brandon E., Camryn M., Tyler B., Maniya T., Kaitlyn G., Destiney R., Sole’ H., Deja M. Tweedle Dee- Kayleigh F. Tweedle Dum- Tynigie R. Rose- Kristina M. Petunia- Cindy M. Lily- Katie B. Violet- Briana J. Daisy- Da’Johnna F. Flower Chorus- Keonia J., Shalaya F., Tricity R. and named flowers Caterpillar- Alex M. Mad Hatter- Andrew L. March Hare- Glenn F. Royal Cardsmen- ALL 3 Diamonds- Shemar H. 4 Spades- Aaron M. Ace Spades- Kevin T. 5 Diamonds- Abraham S. 2 Clubs- Ben S. Queen of Hearts- Alyceanna W. King of Hearts- Ethan G. Ensemble/Chorus- Katie B. Kevin T. Ben S. Briana J. Kristina M. Latasia C. Da’Johnna F. Shalaya F. Shamara H. Shemar H. Cindy M. Keonia J. Tricity R. Kaitlyn G. Sole’ H. Aaron M. Deja M. Destiney R. Abraham S. Chanyce S. Kayla M. Camryn M. Destiney A. Tyler B. Mariscia M. Brandon E. Bar’Shon B. Bridgette B. Maniya T. Amari L. Dodgsonland—ALL I’m Late—4th Very Good Advice—4th Grade Ocean of Tears—Dodo, Rock Lobsters, Sea Creatures (select 3rd and 4th) I’m Late-Reprise—4th How D’ye Do and Shakes Hands—Tweedles and Alice The Golden Afternoon—5th Grade girls Zip-a-dee-do-dah—4th and 5th The Unbirthday Song—5th Grade Painting the Roses Red—ALL Simon Says—Queen, Alice (ALL cardsmen) The Unbirthday Song-Reprise—Mad Hatter, Queen, King, 5th Grade Who Are You?—Tweedles, Flowers, Alice, Mad Hatter, White Rabbit, Queen & Named Cardsmen Alice in Wonderland: Finale—ALL Zip-a-dee-doo-dah: Bows—ALL . -

Saki / H.H. Munro 1870-1916 Bios

Saki / H.H. Munro 1870-1916 Bios http://www.litgothic.com/Authors/saki.html Up to now, little has been known about Hector Hugh Munro except that he used the pen name “Saki”; that he wrote a number of witty short stories, two novels, several plays, and a history of Russia; and that he was killed in World War I. His friend Rothay Reynolds published “A Memoir of H. H. Munro” in Saki’s The Toys of Peace (1919), and Munro’s sister Ethel furnished a brief “Biography of Saki” for a posthumous collection of his work entitled The Square Egg and Other Sketches (1924). A. J. Langguth’s Saki is the first full-length biography of the man who, during his brief writing career, published a succession of bright, satirical, and sometimes perfectly crafted short stories that have entertained and amused readers in many countries for well over a half-century. Hector Munro was the third child of Charles Augustus Munro, a British police officer in Burma, and his wife Mary Frances. The children were all born in Burma. Pregnant with her fourth child, Mrs. Munro was brought with the children to live with her husband’s family in England until the child arrived. Frightened by the charge of a runaway cow on a country lane, Mrs. Munro died after a miscarriage. Since the widowed father had to return to Burma, the children — Charles, Ethel, and Hector — were left with their Munro grandmother and her two dominating and mutually antagonistic spinster daughters, Charlotte (“Aunt Tom”) and Augusta. This situation would years later provide incidents, characters, and themes for a number of Hector Munro’s short stories as well as this epitaph for Augusta by Ethel: “A woman of ungovernable temper, of fierce likes and dislikes, imperious, a moral coward, possessing no brains worth speaking of, and a primitive disposition. -

In Commemoration of Hector Munro, 'Saki' Transcript

The grinning shadow that sat at the feast: In commemoration of Hector Munro, 'Saki' Transcript Date: Tuesday, 14 November 2006 - 12:00AM The Grinning Shadow that sat at the Feast: an appreciation of the life and work of Hector Munro 'Saki' Professor Tim Connell Hector Munro was a man of many parts, and although he died relatively young, he lived through a time of considerable change, had a number of quite separate careers and a very broad range of interests. He was also a competent linguist who spoke Russian, German and French. Today is the 90th anniversary of his death in action on the Somme, and I would like to review his importance not only as a writer but also as a figure in his own time. Early years to c.1902 Like so many Victorians, he was born into a family with a long record of colonial service, and it is quite confusing to see how many Hector Munros there are with a military or colonial background. Our Hector’s most famous ancestor is commemorated in a well-known piece at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Tippoo's Tiger shows a man being eaten by a mechanical tiger and the machine emits both roaring and groaning sounds. 1 Hector's grandfather was an Admiral, and his father was in the Burma Police. The family was hit by tragedy when Hector's mother was killed in a bizarre accident involving a runaway cow. It is curious that strange events involving animals should form such a common feature of Hector's writing 2 but this may also derive from his upbringing in the Devonshire countryside and a home that was dominated by the two strangest creatures of all - Aunt Augusta and Aunt Tom. -

Orecchio Acerbo Rights List Spring 2021

orecchio acerbo editore Foreign rights catalog Winner of the BoP · Best Children’s PuBlisher of the Year 2017, euroPe Spring 2021 picture books daybrEak NEW by Daniel Fehr illustrations Elena Rotondo for children 4 years and older pp. 28 | cm. 23 x 21 ISBN 9788832070651 | July 2021 today NEW by Daniel Fehr big quEstioNs | grEat advENturEs illustrations Simone Rea WaitiNg for Walt for children 4 years and older by Daniel Fehr The story is about a young boy and his father. pp. 64 | cm. 17 x 24 illustrations Maja Celjia In the middle of the night they leave their house. ISBN 9788832070590 | April 2021 for children 5 years and older For the boy it is the first time that he leaves home pp. 32 | cm. 24 x 32 | May 2020 at this time of the night when normally uNdEr thE gazE of timE | rEcouNtiNg thE prEsENt he is asleep. As they walk through the forest storiEs of thE visioNary aNd thE absurd laughtEr aNd smilEs the flashlight of the boy “turns on” part A father who is leaving. Two brothers. A long wait. of the vegetation and at the same time the rest But together it is easier, together it is easy disappear. He turns off the flashlight and “turns on” to be strong. The older brother reads books Two kids are waiting for Walt. But who is Walt? all his senses: he experiences the darkness, to the younger one who can’t read yet but can And, if Walt was there with them, what would the sounds of the forest, the sound of his father, at least choose the book; then they go together they all do together? They would have a lot the roughness of the ground, the smells… on a secret mission: is every mission of spies of fun, because when he is there he always He dares not ask for the space and time secret? Then one goes to play football, the other has crazy ideas. -

English Literature, History, Children's Books And

LONDON 13 DECEMBER 2016 DECEMBER 13 LONDON HISTORY, CHILDREN’S CHILDREN’S HISTORY, ENGLISH LITERATURE, ENGLISH LITERATURE, BOOKS AND BOOKS ILLUSTRATIONS LONDON ENGLISH LITERATURE, HISTORY, CHILDREN’S BOOKS AND ILLUSTRATIONS 13 DECEMBER 2016 L16408 ENGLISH LITERATURE, HISTORY, CHILDREN’S BOOKS AND ILLUSTRATIONS FRONT COVER LOT 67 (DETAIL) BACK COVER LOT 317 THIS PAGE LOT 30 (DETAIL) ENGLISH LITERATURE, HISTORY, CHILDREN’S BOOKS AND ILLUSTRATIONS AUCTION IN LONDON 13 DECEMBER 2016 SALE L16408 SESSION ONE: 10 AM SESSION TWO: 2.30 PM EXHIBITION Friday 9 December 9 am-4.30 pm Saturday 10 December 12 noon-5 pm Sunday 11 December 12 noon-5 pm Monday 12 December 9 am-7 pm 34-35 New Bond Street London, W1A 2AA +44 (0)20 7293 5000 sothebys.com THIS PAGE LOT 101 (DETAIL) SPECIALISTS AND AUCTION ENQUIRIES For further information on lots in this auction please contact any of the specialists listed below. SALE NUMBER SALE ADMINISTRATOR L16408 “BABBITTY” Lukas Baumann [email protected] BIDS DEPARTMENT +44 (0)20 7293 5287 +44 (0)20 7293 5283 fax +44 (0)20 7293 5904 fax +44 (0)20 7293 6255 [email protected] POST SALE SERVICES Kristy Robinson Telephone bid requests should Post Sale Manager Peter Selley Dr. Philip W. Errington be received 24 hours prior FOR PAYMENT, DELIVERY Specialist Specialist to the sale. This service is AND COLLECTION +44 (0)20 7293 5295 +44 (0)20 7293 5302 offered for lots with a low estimate +44 (0)20 7293 5220 [email protected] [email protected] of £2,000 and above. -

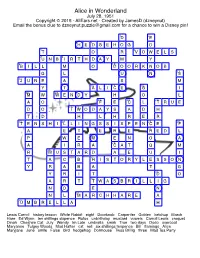

Alice in Wonderland

Alice in Wonderland July 28, 1951 Copyright © 2015 - AllEars.net - Created by JamesD (dzneynut) Email the bonus clue to [email protected] for a chance to win a Disney pin! 1 2 D E 3 4 H E D G E H O G D 5 6 T O R V O W E L S 7 8 U N B I R T H D A Y M Y 9 10 B I L L M O D O O R K N O B 11 G L U N S 12 J U N E A S M 13 14 15 Y T A L I C E G I 16 17 M W W E N D Y H O L 18 19 20 A O F E C L T R U E 21 22 D O T W O D A Y S A D H T D H L H R E R 23 24 25 26 T E N S H I L L I N G S S I X P E N C E F 27 A E T E R E R E D L 28 P W E M E N O A 29 A I R A C A T Q M 30 R M U S T A R D A E U I 31 T A C B H I S T O R Y L E S S O N Y R A B A T G 32 Y R I T D O 33 A R T T W A S B R I L L I G N O E N 34 N L M A R C H H A R E A 35 U M B R E L L A H Lewis Carroll history lesson White Rabbit eight Doorknob Carpenter Golden ketchup March Hare Ed Wynn ten shillings sixpence Rufus unbirthday mustard vowels Carroll Lewis croquet Dinah Cheshire Cat July Wendy Im Late umbrella smirk True two days Dodo overcoat Maryanne Tulgey Woods Mad Hatter cat red six shillings tenpence Bill flamingo Alice Maryjane June smile False bird hedgehog Dormouse Twas Brillig three Mad Tea Party ★ Thurl Ravenscroft, a member of the singing group, the Mellomen, who sing #27 Across, appears to have lost his head while singing a familiar song in what popular theme park attraction? (2 words) [HAUNTEDMANSION] Across Down 3. -

Beasts and Super-Beasts: by Saki Online

j1Zfo [E-BOOK] Beasts and Super-Beasts: by Saki Online [j1Zfo.ebook] Beasts and Super-Beasts: by Saki Pdf Free Saki Saki *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook 2017-01-07 2017-01-07File Name: B01NBSEDIW | File size: 52.Mb Saki Saki : Beasts and Super-Beasts: by Saki before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Beasts and Super-Beasts: by Saki: 5 of 5 people found the following review helpful. Saki at his bestBy Robert GuttmanBeasts and Super-Beasts comprises thirty-seven short stories from the pen of the incomparable Saki, which was the pen-name for H. H. Munro. Saki's ironic and witty stories chronicled the British upper class during the Edwardian period, the era that represented the zenith of British power and complacency just before the cataclysm of World War I. The quality of his wit and satiric humor are of the very highest order, comparable to very best of Oscar Wilde and Ambrose Bierce. As with Bierce, a touch of cruelty was often present in Saki's humor. In addition, Saki also shared with Bierce a taste for the supernatural, a quality which comes across in many of the stories in this particular collection.Reading Saki is an absolute must for any aspiring writer, and an absolute pleasure for readers everywhere.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Gotta love Saki!By Kevin BeachyIf you like Mark Twain's particular strain of sarcastic humor, you gotta try Saki. -

Honour List 2018 © International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY), 2018

HONOUR LIST 2018 © International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY), 2018 IBBY Secretariat Nonnenweg 12, Postfach CH-4009 Basel, Switzerland Tel. [int. +4161] 272 29 17 Fax [int. +4161] 272 27 57 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.ibby.org Book selection and documentation: IBBY National Sections Editors: Susan Dewhirst, Liz Page and Luzmaria Stauffenegger Design and Cover: Vischer Vettiger Hartmann, Basel Lithography: VVH, Basel Printing: China Children’s Press and Publication Group (CCPPG) Cover illustration: Motifs from nominated books (Nos. 16, 36, 54, 57, 73, 77, 81, 86, 102, www.ijb.de 104, 108, 109, 125 ) We wish to kindly thank the International Youth Library, Munich for their help with the Bibliographic data and subject headings, and the China Children’s Press and Publication Group for their generous sponsoring of the printing of this catalogue. IBBY Honour List 2018 IBBY Honour List 2018 The IBBY Honour List is a biennial selection of This activity is one of the most effective ways of We use standard British English for the spelling outstanding, recently published children’s books, furthering IBBY’s objective of encouraging inter- foreign names of people and places. Furthermore, honouring writers, illustrators and translators national understanding and cooperation through we have respected the way in which the nomi- from IBBY member countries. children’s literature. nees themselves spell their names in Latin letters. As a general rule, we have written published The 2018 Honour List comprises 191 nomina- An IBBY Honour List has been published every book titles in italics and, whenever possible, tions in 50 different languages from 61 countries. -

Alice in Wonderland A Fantasy with Music. Last Edit

Alice in Wonderland A fantasy with music. Last edit: 1/20/19 Adapted from the novel by Dave Alan Thomas Lyrics by Dave Alan Thomas (“Dreaming” based on a poem by Lewis Carroll) Music by AJ Neaher CAST OF CHARACTERS: All roles will be played by a ten-member ensemble (plus, a pianist) as follows: ALICE A: (MAD HATTER/MARCH HARE/DORMOUSE) B: (WHITE RABBIT) C: (DUCHESS/DUCK) D: (QUEEN OF HEARTS/DODO) E: (GRYPHON/EAGLET/PIGEON/PIG) F: (MOCK TURTLE/EAGLET/BILL THE LIZARD/FISH FOOTMAN) G: (CHESHIRE CAT/MOUSE/GUARD) H: (KNAVE OF HEARTS/FROG FOOTMAN) I: (CATERPILLAR/PAT THE HEDGEHOG/COOK/EXECUTIONER) Narrator* Singer** Pianist*** *Any member that suits the staging best for lines of the the “Narrator” This could be a character that breaks the fourth wall while also playing a character within a scene or it can be one of the players that is not already currently assigned to a character in any given scene. **Although the Mad Hatter is a likely candidate to sing lead on these songs, as he is also the guitarist (or extra musician) they have a “Greek chorus” quality that would lend them to any member of the ensemble, other than Alice, to take part in or to sing lead. That assignment can be at the discretion of the director and music/vocal director, based on the best attributes and abilities of your cast and directorial concept. They will simply be listed as SINGER in the script. ***The pianist is the only member of the show that remains a musician throughout the dream and does not take on other characters. -

The Daily Egyptian, February 10, 1972

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC February 1972 Daily Egyptian 1972 2-10-1972 The aiD ly Egyptian, February 10, 1972 Daily Egyptian Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_February1972 Volume 53, Issue 86 Recommended Citation , . "The aiD ly Egyptian, February 10, 1972." (Feb 1972). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daily Egyptian 1972 at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in February 1972 by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'Daily Egyptian Southern Illinois University ThUrsday. Febtuaty 10. 1972- Vol. 53. No. 86 Derge postpones t=decisions on issues By Randy Thomas with the current tight money situation Daily Egyptian Starr Writer at SIU . He said that in the past money was Student Senators had a lot of readily available to the universities in questions for SIU President David Illinois. He pointed out that SIU will no R. Derge at a senate meeting Wed longer be able to get money from the (t>nesday night, but the new ly appointed Illinois Board of Higher Education .. president provided few answer . (lBHE) on the basis of quantitative ex Derge refused to take a stand on the pansion. controversial Doug Allen tenurc case, " In the future all monay will come on the Center for Vietnamese Studies, the the basis of qualitative educational VTl phase out program, the Expro programs," he said. report on the Daily Egyptian and the When asked to comment on an article Meeting the senate tradition of granting the University in Wednesday's Daily Egyptian concer New SlU President David R.