"Animals in Saki's Short Stories Within the Context of Imperialism: a Non

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saki / H.H. Munro 1870-1916 Bios

Saki / H.H. Munro 1870-1916 Bios http://www.litgothic.com/Authors/saki.html Up to now, little has been known about Hector Hugh Munro except that he used the pen name “Saki”; that he wrote a number of witty short stories, two novels, several plays, and a history of Russia; and that he was killed in World War I. His friend Rothay Reynolds published “A Memoir of H. H. Munro” in Saki’s The Toys of Peace (1919), and Munro’s sister Ethel furnished a brief “Biography of Saki” for a posthumous collection of his work entitled The Square Egg and Other Sketches (1924). A. J. Langguth’s Saki is the first full-length biography of the man who, during his brief writing career, published a succession of bright, satirical, and sometimes perfectly crafted short stories that have entertained and amused readers in many countries for well over a half-century. Hector Munro was the third child of Charles Augustus Munro, a British police officer in Burma, and his wife Mary Frances. The children were all born in Burma. Pregnant with her fourth child, Mrs. Munro was brought with the children to live with her husband’s family in England until the child arrived. Frightened by the charge of a runaway cow on a country lane, Mrs. Munro died after a miscarriage. Since the widowed father had to return to Burma, the children — Charles, Ethel, and Hector — were left with their Munro grandmother and her two dominating and mutually antagonistic spinster daughters, Charlotte (“Aunt Tom”) and Augusta. This situation would years later provide incidents, characters, and themes for a number of Hector Munro’s short stories as well as this epitaph for Augusta by Ethel: “A woman of ungovernable temper, of fierce likes and dislikes, imperious, a moral coward, possessing no brains worth speaking of, and a primitive disposition. -

In Commemoration of Hector Munro, 'Saki' Transcript

The grinning shadow that sat at the feast: In commemoration of Hector Munro, 'Saki' Transcript Date: Tuesday, 14 November 2006 - 12:00AM The Grinning Shadow that sat at the Feast: an appreciation of the life and work of Hector Munro 'Saki' Professor Tim Connell Hector Munro was a man of many parts, and although he died relatively young, he lived through a time of considerable change, had a number of quite separate careers and a very broad range of interests. He was also a competent linguist who spoke Russian, German and French. Today is the 90th anniversary of his death in action on the Somme, and I would like to review his importance not only as a writer but also as a figure in his own time. Early years to c.1902 Like so many Victorians, he was born into a family with a long record of colonial service, and it is quite confusing to see how many Hector Munros there are with a military or colonial background. Our Hector’s most famous ancestor is commemorated in a well-known piece at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Tippoo's Tiger shows a man being eaten by a mechanical tiger and the machine emits both roaring and groaning sounds. 1 Hector's grandfather was an Admiral, and his father was in the Burma Police. The family was hit by tragedy when Hector's mother was killed in a bizarre accident involving a runaway cow. It is curious that strange events involving animals should form such a common feature of Hector's writing 2 but this may also derive from his upbringing in the Devonshire countryside and a home that was dominated by the two strangest creatures of all - Aunt Augusta and Aunt Tom. -

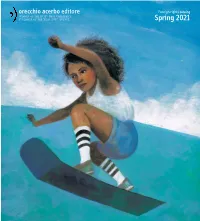

Orecchio Acerbo Rights List Spring 2021

orecchio acerbo editore Foreign rights catalog Winner of the BoP · Best Children’s PuBlisher of the Year 2017, euroPe Spring 2021 picture books daybrEak NEW by Daniel Fehr illustrations Elena Rotondo for children 4 years and older pp. 28 | cm. 23 x 21 ISBN 9788832070651 | July 2021 today NEW by Daniel Fehr big quEstioNs | grEat advENturEs illustrations Simone Rea WaitiNg for Walt for children 4 years and older by Daniel Fehr The story is about a young boy and his father. pp. 64 | cm. 17 x 24 illustrations Maja Celjia In the middle of the night they leave their house. ISBN 9788832070590 | April 2021 for children 5 years and older For the boy it is the first time that he leaves home pp. 32 | cm. 24 x 32 | May 2020 at this time of the night when normally uNdEr thE gazE of timE | rEcouNtiNg thE prEsENt he is asleep. As they walk through the forest storiEs of thE visioNary aNd thE absurd laughtEr aNd smilEs the flashlight of the boy “turns on” part A father who is leaving. Two brothers. A long wait. of the vegetation and at the same time the rest But together it is easier, together it is easy disappear. He turns off the flashlight and “turns on” to be strong. The older brother reads books Two kids are waiting for Walt. But who is Walt? all his senses: he experiences the darkness, to the younger one who can’t read yet but can And, if Walt was there with them, what would the sounds of the forest, the sound of his father, at least choose the book; then they go together they all do together? They would have a lot the roughness of the ground, the smells… on a secret mission: is every mission of spies of fun, because when he is there he always He dares not ask for the space and time secret? Then one goes to play football, the other has crazy ideas. -

Beasts and Super-Beasts: by Saki Online

j1Zfo [E-BOOK] Beasts and Super-Beasts: by Saki Online [j1Zfo.ebook] Beasts and Super-Beasts: by Saki Pdf Free Saki Saki *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook 2017-01-07 2017-01-07File Name: B01NBSEDIW | File size: 52.Mb Saki Saki : Beasts and Super-Beasts: by Saki before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Beasts and Super-Beasts: by Saki: 5 of 5 people found the following review helpful. Saki at his bestBy Robert GuttmanBeasts and Super-Beasts comprises thirty-seven short stories from the pen of the incomparable Saki, which was the pen-name for H. H. Munro. Saki's ironic and witty stories chronicled the British upper class during the Edwardian period, the era that represented the zenith of British power and complacency just before the cataclysm of World War I. The quality of his wit and satiric humor are of the very highest order, comparable to very best of Oscar Wilde and Ambrose Bierce. As with Bierce, a touch of cruelty was often present in Saki's humor. In addition, Saki also shared with Bierce a taste for the supernatural, a quality which comes across in many of the stories in this particular collection.Reading Saki is an absolute must for any aspiring writer, and an absolute pleasure for readers everywhere.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Gotta love Saki!By Kevin BeachyIf you like Mark Twain's particular strain of sarcastic humor, you gotta try Saki. -

Honour List 2018 © International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY), 2018

HONOUR LIST 2018 © International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY), 2018 IBBY Secretariat Nonnenweg 12, Postfach CH-4009 Basel, Switzerland Tel. [int. +4161] 272 29 17 Fax [int. +4161] 272 27 57 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.ibby.org Book selection and documentation: IBBY National Sections Editors: Susan Dewhirst, Liz Page and Luzmaria Stauffenegger Design and Cover: Vischer Vettiger Hartmann, Basel Lithography: VVH, Basel Printing: China Children’s Press and Publication Group (CCPPG) Cover illustration: Motifs from nominated books (Nos. 16, 36, 54, 57, 73, 77, 81, 86, 102, www.ijb.de 104, 108, 109, 125 ) We wish to kindly thank the International Youth Library, Munich for their help with the Bibliographic data and subject headings, and the China Children’s Press and Publication Group for their generous sponsoring of the printing of this catalogue. IBBY Honour List 2018 IBBY Honour List 2018 The IBBY Honour List is a biennial selection of This activity is one of the most effective ways of We use standard British English for the spelling outstanding, recently published children’s books, furthering IBBY’s objective of encouraging inter- foreign names of people and places. Furthermore, honouring writers, illustrators and translators national understanding and cooperation through we have respected the way in which the nomi- from IBBY member countries. children’s literature. nees themselves spell their names in Latin letters. As a general rule, we have written published The 2018 Honour List comprises 191 nomina- An IBBY Honour List has been published every book titles in italics and, whenever possible, tions in 50 different languages from 61 countries. -

The Daily Egyptian, February 10, 1972

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC February 1972 Daily Egyptian 1972 2-10-1972 The aiD ly Egyptian, February 10, 1972 Daily Egyptian Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_February1972 Volume 53, Issue 86 Recommended Citation , . "The aiD ly Egyptian, February 10, 1972." (Feb 1972). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daily Egyptian 1972 at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in February 1972 by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'Daily Egyptian Southern Illinois University ThUrsday. Febtuaty 10. 1972- Vol. 53. No. 86 Derge postpones t=decisions on issues By Randy Thomas with the current tight money situation Daily Egyptian Starr Writer at SIU . He said that in the past money was Student Senators had a lot of readily available to the universities in questions for SIU President David Illinois. He pointed out that SIU will no R. Derge at a senate meeting Wed longer be able to get money from the (t>nesday night, but the new ly appointed Illinois Board of Higher Education .. president provided few answer . (lBHE) on the basis of quantitative ex Derge refused to take a stand on the pansion. controversial Doug Allen tenurc case, " In the future all monay will come on the Center for Vietnamese Studies, the the basis of qualitative educational VTl phase out program, the Expro programs," he said. report on the Daily Egyptian and the When asked to comment on an article Meeting the senate tradition of granting the University in Wednesday's Daily Egyptian concer New SlU President David R. -

The Enchanted Hour

THE ENCHANTED HOUR THE MIRACULOUS POWER OF READING ALOUD IN THE AGE OF DISTRACTION MEGHAN COX GURDON HARPER An Imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers the enchanted hour. Copyright © 2019 by Meghan Cox Gurdon. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address HarperCollins Publishers, 195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007. HarperCollins books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. For information, please email the Special Markets Department at [email protected]. first edition Designed by Fritz Metsch Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data has been applied for. ISBN 978-0-06-256281-4 19 20 21 22 23 lsc 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 READ- ALOUD BOOKS MENTIONED IN THE ENCHANTEDr HOUR All highly recommended! 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, by Jules Verne Abel’s Island, by William Steig The Absolutely True Diary of a Part- Time Indian, by Sherman Alexie Adam of the Road, by Elizabeth Gray, illustrated by Robert Lawson The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, by Mark Twain Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, by Lewis Carroll, illustrated by John Tenniel The Amazing Bone, by William Steig Andrew’s Loose Tooth, by Robert Munsch Around the World with Ant and Bee, by Angela Banner Art & Max, by David Wiesner Art Up Close, by Claire d’Harcourt The BabyLit Series, by Jennifer Adams, illustrated by Alison Oliver -

{PDF EPUB} Another Trio of Saki the Elka Holiday Taskthe

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Another Trio of Saki The ElkA Holiday TaskThe Schartz- Metterklume Method by Saki The Complete Saki (1933) So far I have read Reginald which is wonderful - review here: Saki (H.H. Munro) wrote genteel - but cutting - English satire in the years before World War I, a war he did not survive. He easily stands comparison with his peer in the next generation, P.G. Wodehouse. This is a compendium of his entire works (though there is a biography in circulation which claims to have four previously uncollected stories). Perhaps he is best known for the short story 'Sredni Vashtar', all about a boy and his ferret, which turns from an Edwardian parlour piece into horror without batting an eyelid. This is one of Saki's trademarks; the unexpected turn occurs in many of his stories, making them all the more delicious. I have other favourites; perhaps my top one is 'Filboid Studge'; a struggling breakfast-food entrepreneur engages an equally struggling artist who wants to marry his daughter to promote his disgusting cereal, and he makes such a good job that a) the cereal becomes a best-seller, and b) his daughter is now too good for the artist. The cereal is described with relish, as it were: "In small kitchens, solemn pig-tailed daughters helped depressed mothers perform the primitive ritual of its preparation." God, it sounds awful! The collection includes three plays and three novels, including his future-war contribution, "When William came", all about London under the occupation of the Kaiser's army. -

Knight Letter No. 85

^ ^ KNIGHT LETTER ^ ^^ ^ The Lewis Carroll Society ofNorth America Winter 2010 Volume II Issue 15 Number 85 Knight Letter is the official magazine of the Lewis Carroll Society of North America. It is published twice a year and is distributed free to all members. Editorial correspondence should be sent to the Editor in Chief at [email protected]. SUBMISSIONS Submissions for The Rectory Umbrella and Mischmasch should be sent to [email protected]. Submissions and suggestions for Serendipity and Sic Sic Sic should be sent to [email protected]. Submissions and suggestions for From OurFar-Flung Correspondents should be sent to [email protected]. © 2010 The Lewis Carroll Society of North America ISSN 0193-886X Sarah Adams-Kiddy, Editor in Chief Mahendra Singh, Editor, The Rectory Umbrella Sarah Adams-Kiddy ^ Ray Kiddy, Editors, Mischmasch James Welsch 6^ Rachel Eley, Editors, From Our Far-Rung Correspondents Mark Burstein, Production Editor Andrew H. Ogus, Designer THE LEWIS CARROLL SOCIETY OF NORTH AMERICA President: Mark Burstein, [email protected] Vice-President: Cindy Watte r, [email protected] Secretary: Clare Imholtz, [email protected] www.LewisCarroll . org Annual membership dues are U.S. $35 (regular), $50 (international), and $100 (sustaining). Subscriptions, correspondence, and inquiries should be addressed to: Clare Imholtz, LCSNA Secretary 11935 Beltsville Dr. Beltsville, Maryland 20705 Additional Contributors to This Issue Barbara Adams, Ruth Berman, Angelica Carpenter, Bonnie Hagerman, Alan Tannenbaum, Cindy Watter On the cover: Secret Garden, digital collage by Adriana Peliano. Seepage 21. 1 -^ -^0^ ^ CONTENTS H^ i^y„s^ ^S ^i^"^^^ ^ THe ReCTORY UMBRSLLA OF BOOKS AND THINGS m Livefrom Lincoln Center Evermore Everson 's Everytype! 45 MARK BURSTEIN MARK BURSTEIN Keith Shepard's Wonderland Revisited, Meeting Mr. -

Scanned Using Library Document Station 5022

Reading can be one of the many fun activities children fill their summer time with. Research has shown it is also much more! Children who participate in public library summer reading programs not only avoid the “summer slide” in learning, but also score higher on reading achievement tests than those who do not participate. The books on this list come highly recommended by kid readers from all over the country and may also be available in ebook, audio book, braille, and large print formats. This summer, encourage your chiid to participate in the summer programs happening at your library. Association for Library Service to Children www.ala.org/alsc The 2016 Summer Reading Book List was created by members of the Association for Library Service to Children's Quicklists Consulting Committee. For more booklists from ALSC visit www.ala.org/alsc/booklists. GRADES 6-8 Masterminds by Gordon Saki Yamamoto does not Korman want to spend her summer SUMMER READING LIST Balzer + Bray, 2015, ISBN: 9780062299963 vacation visiting her Dead to Me Fish in a Tree by Lynda campaign to make a beloved Beetle Boy by M. G. Leonard After living in a perfect town grandma’s small village. Illustrated by Julia Sarda by Mary McCoy Mullaly Hunt teacher’s favorite book “go his whole life, Eli discovers Things get more interesting Disney-Hyperion, 2015, ISBN: Penguin/Nancy Paulsen Books, Scholastic/Chicken House, 2016, viral.” than she expected when she ISBN: 9780545853460 9781423187127 2015, ISBN: 9780399162596 there are secrets that will unintentionally invokes a A giant talking beetle and cast Veronica Mars meets L.A. -

Block-3 Structure Words

BEGLA-137 Indira Gandhi National Open University LANGUAGE THROUGH School of Humanities LITERATURE Block 3 Structure words Block Introduction UNIT 9 Structure Words-1 UNIT 10 Structure Words-2 Auxiliaries UNIT 11 Structure Words in Discourse-1 UNIT 12 Structure Words in Discourse-2 2 Course Introduction Language through Literature (BEGLA 137) (CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM) Credit weightage: 6 credits Language Through Literature which has been adapted from BEGE-101 is aimed at providing a lucid account of how even the most common elements of language are used dexterously and aesthetically in literature/oratory to please, entertain, persuade, gratify and create aesthetic appeal. As a matter of fact, literature is nothing but a creative and imaginative use of language. This course will enable you to not only understand the various and dynamic ways in which writers/orators use language but also comprehend and appreciate literary/rhetorical pieces better and derive greater pleasure from them. This course will primarily deal with literal versus metaphorical meaning, literary and rhetorical devices and an understanding of the development of discourse. This course seeks to equip you with awareness of some of the important aspects of English usage through the study of representative samples of literary works produced in English. The course is divided into 4 blocks of about 4 units each. Block 1 deals with extension of meaning, multiple meanings and overlap of meaning in the context of language acquisition process through four units/chapters. Block 2 has four units that deal with confusion of semantic and structural criteria and escaping wrong analogies including studying literary texts. -

India/Postcolonial Focus

Fall 2009 | Volume 26 | Number 1 India/Postcolonial Focus India/Postcolonial VOLUME 26 | NUMBER 1 | FALL 2009 | $8.00 Deriving from the German weben—to weave—weber translates into the literal and figurative “weaver” of textiles and texts.Weber (the word is the same in singular and plural) are the artisans of textures and discourse, the artists of the beautiful fabricating the warp and weft of language into ever-changing pattterns. Weber, the journal, understands itself as a tapestry of verbal and visual texts, a weave made from the threads of words and images. Of Empresses, Empires, and Jewels Benjamin Disraeli, several-time British Prime Minister, famously dubbed India “a jewel in the Crown of England.” A long-term political moderate of the British Conservative Party, Disraeli advocated maintaining rather than expanding British interests. He eventually promoted expansion of British power when it became clear that Russia had increased its sphere of influence beyond the Balkans into the Far East. (Readers of Rudyard Kipling’s Kim may remember these territorial disputes in the Himalayas known as the “Great Game.”) In his private correspondence with Queen Victoria, he pledged “to clear Central Asia of Muscovites and drive them into the Caspian.” One step to secure British advantage was the purchase of 44% of the shares of the Suez Canal Company with the help of Lionel de Rothchild in 1875 through a short-term loan. Disraeli exercised this act of strategic genius with the secret consent of the Queen, but without the consent of Parliament and over resistance from his own cabinet.