Before and After Superflat Before And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lvmh 2015 — Annual Report

LVMH 2015 — ANNUAL REPORT GROUP WHO WE ARE A creative universe of men and women passionate about their profession and driven by the desire to innovate and achieve. A globally unrivalled group of powerfully evocative brands 03 CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE and great names that are synonymous with 06 FONDATION LOUIS VUITTON the history of luxury. A natural alliance between art and craftsmanship, dominated by creativity, 10 INTERVIEW WITH THE GROUP virtuosity and quality. A remarkable economic MANAGING DIRECTOR success story with more than 125,000 employees 12 COMMITMENTS worldwide and global leadership in the manufacture and distribution of luxury goods. 14 GOVERNANCE AND ORGANIZATION A global vision dedicated to serving the needs 16 BUSINESS GROUPS of every customer. The successful marriage of cultures grounded in tradition and elegance 18 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS with the most advanced product presentation, 22 TALENTS industrial organization and management techniques. A singular mix of talent, daring 30 SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY and thoroughness in the quest for excellence. 34 RESPONSIBLE PARTNERSHIPS A unique enterprise that stands out in its sector. Our philosophy: 36 ENVIRONMENT PASSIONATE ABOUT CREATIVITY. 44 CORPORATE SPONSORSHIP 46 SHAREHOLDERS 48 FINANCE THE VALUES OF LVMH Innovation and creativity Because our future success will come from the desire that our new products elicit while respecting the roots of our Maisons. Excellence of products and service Because we embody what is most noble and quality-endowed in the artisan world. Entrepreneurship Because this is the key to our ability to react and our motivation to manage our businesses as startups. 02 / 50 LVMH 2015 — Chairman’s message AFFIRMING OUR VALUES AND OUR VISION FOR THE GROUP — LVMH THRIVES ON CREATION, ON TALENTED MEN AND WOMEN AND ON THEIR DESIRE FOR EXCELLENCE. -

Men and Masculinities in the Changing Japanese Family

Thesis for Doctor of Philosophy in Asian & Middle Eastern Studies Men and Masculinities in the Changing Japanese Family by Hiroko Umegaki Lucy Cavendish College Submitted November 2017 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Asian & Middle Eastern Studies provided by Apollo View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk CORE brought to you by 1 Preface This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit of the relevant Degree Committee. 2 Acknowledgments Without her ever knowing, my grandmother provided the initial inspiration for my research: this thesis is dedicated to her. Little did I appreciate at the time where this line of enquiry would lead me, and I would not have stayed on this path were it not for my family, my husband, children, parents and extended family: thank you. -

The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2009 The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M. Stockins University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Stockins, Jennifer M., The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney, Master of Arts - Research thesis, University of Wollongong. School of Art and Design, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/3164 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree Master of Arts - Research (MA-Res) UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG Jennifer M. Stockins, BCA (Hons) Faculty of Creative Arts, School of Art and Design 2009 ii Stockins Statement of Declaration I certify that this thesis has not been submitted for a degree to any other university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, except where due reference has been made in the text. Jennifer M. Stockins iii Stockins Abstract Manga (Japanese comic books), Anime (Japanese animation) and Superflat (the contemporary art by movement created Takashi Murakami) all share a common ancestry in the woodblock prints of the Edo period, which were once mass-produced as a form of entertainment. -

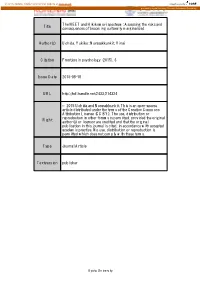

Title the NEET and Hikikomori Spectrum

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository The NEET and Hikikomori spectrum: Assessing the risks and Title consequences of becoming culturally marginalized. Author(s) Uchida, Yukiko; Norasakkunkit, Vinai Citation Frontiers in psychology (2015), 6 Issue Date 2015-08-18 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/214324 © 2015 Uchida and Norasakkunkit. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original Right author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 18 August 2015 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01117 The NEET and Hikikomori spectrum: Assessing the risks and consequences of becoming culturally marginalized Yukiko Uchida 1* and Vinai Norasakkunkit 2 1 Kokoro Research Center, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan, 2 Department of Psychology, Gonzaga University, Spokane, WA, USA An increasing number of young people are becoming socially and economically marginalized in Japan under economic stagnation and pressures to be more globally competitive in a post-industrial economy. The phenomena of NEET/Hikikomori (occupational/social withdrawal) have attracted global attention in recent years. Though the behavioral symptoms of NEET and Hikikomori can be differentiated, some commonalities in psychological features can be found. Specifically, we believe that both NEET and Hikikomori show psychological tendencies that deviate from those Edited by: Tuukka Hannu Ilmari Toivonen, governed by mainstream cultural attitudes, values, and behaviors, with the difference University of London, UK between NEET and Hikikomori being largely a matter of degree. -

Logistics Capacity Assessment Nepal

IA LCA – Nepal 2009 Version 1.05 Logistics Capacity Assessment Nepal Country Name Nepal Official Name Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal Regional Bureau Bangkok, Thailand Assessment Assessment Date: From 16 October 2009 To: 6 November 2009 Name of the assessors Rich Moseanko – World Vision International John Jung – World Vision International Rajendra Kumar Lal – World Food Programme, Nepal Country Office Title/position Email contact At HQ: [email protected] 1/105 IA LCA – Nepal 2009 Version 1.05 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Country Profile....................................................................................................................................................................3 1.1. Introduction / Background.........................................................................................................................................5 1.2. Humanitarian Background ........................................................................................................................................6 1.3. National Regulatory Departments/Bureau and Quality Control/Relevant Laboratories ......................................16 1.4. Customs Information...............................................................................................................................................18 2. Logistics Infrastructure .....................................................................................................................................................33 2.1. Port Assessment .....................................................................................................................................................33 -

BERNARD ARNAULT Hennessy 2 2020 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING 3 EXCELLENT PERFORMANCE for LVMH in 2019

ANNUAL2020 GENERAL MEETING JUNE 30, 2020 Louis Vuitton Louis 1 BERNARD ARNAULT Hennessy 2 2020 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING 3 EXCELLENT PERFORMANCE FOR LVMH IN 2019 |Buoyant market despite uncertain geopolitical context |Good progress in all geographic regions |Another record year with double-digit increases in revenue and profit from recurring operations • Revenue: €53.7 bn, + 15% (+ 10% organic) • Profit from recurring operations: €11.5 bn, + 15% |Healthy financial position • Operating free cash flow: €6.2 bn • Adjusted net debt to equity ratio of 16.2% | Agreement with Tiffany, and integration of Belmond 3 JEAN-JACQUES GUIONY Christian Dior Dior Couture Christian 4 2020 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING 5 2019 REVENUE EVOLUTION In millions of euros Organic Structure Currency impact effect 53 670 46 826 +10% + 1% +3% + 15% 2018 2019 The principles used to determine the net impact of exchange rate fluctuations on the revenue of entities reporting in foreign currencies and the net impact of changes in the scope of consolidation are described on page 39 of the 2019 Universal Registration Document. As table totals are calculated based on unrounded figures, there may be slight discrepancies between these totals and the sum of their component figures. 5 2020 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING 6 2019 REVENUE BY BUSINESS GROUP Reported Organic In millions of euros 2018 2019 growth growth* WINES & SPIRITS 5 143 5 576 + 8% + 6% Champagne & Wines 2 369 2 507 + 6% + 4% Cognac & Spirits 2 774 3 069 + 11% + 7% FASHION & LEATHER GOODS 18 455 22 237 + 20% + 17% PERFUMES & COSMETICS 6 092 6 835 + 12% + 9% WATCHES & JEWELRY 4 123 4 405 + 7% + 3% SELECTIVE RETAILING 13 646 14 791 + 8% + 5% OTHERS & ELIMINATIONS (633) (174) -- TOTAL LVMH 46 826 53 670 + 15% + 10% * With comparable structure and exchange rates. -

11Eyes Achannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air

11eyes AChannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air Master Amaenaideyo Angel Beats Angelic Layer Another Ao No Exorcist Appleseed XIII Aquarion Arakawa Under The Bridge Argento Soma Asobi no Iku yo Astarotte no Omocha Asu no Yoichi Asura Cryin' B Gata H Kei Baka to Test Bakemonogatari (and sequels) Baki the Grappler Bakugan Bamboo Blade Banner of Stars Basquash BASToF Syndrome Battle Girls: Time Paradox Beelzebub BenTo Betterman Big O Binbougami ga Black Blood Brothers Black Cat Black Lagoon Blassreiter Blood Lad Blood+ Bludgeoning Angel Dokurochan Blue Drop Bobobo Boku wa Tomodachi Sukunai Brave 10 Btooom Burst Angel Busou Renkin Busou Shinki C3 Campione Cardfight Vanguard Casshern Sins Cat Girl Nuku Nuku Chaos;Head Chobits Chrome Shelled Regios Chuunibyou demo Koi ga Shitai Clannad Claymore Code Geass Cowboy Bebop Coyote Ragtime Show Cuticle Tantei Inaba DFrag Dakara Boku wa, H ga Dekinai Dan Doh Dance in the Vampire Bund Danganronpa Danshi Koukousei no Nichijou Daphne in the Brilliant Blue Darker Than Black Date A Live Deadman Wonderland DearS Death Note Dennou Coil Denpa Onna to Seishun Otoko Densetsu no Yuusha no Densetsu Desert Punk Detroit Metal City Devil May Cry Devil Survivor 2 Diabolik Lovers Disgaea Dna2 Dokkoida Dog Days Dororon EnmaKun Meeramera Ebiten Eden of the East Elemental Gelade Elfen Lied Eureka 7 Eureka 7 AO Excel Saga Eyeshield 21 Fight Ippatsu! JuudenChan Fooly Cooly Fruits Basket Full Metal Alchemist Full Metal Panic Futari Milky Holmes GaRei Zero Gatchaman Crowds Genshiken Getbackers Ghost -

Introduction This Exhibition Celebrates the Spectacular Artistic Tradition

Introduction This exhibition celebrates the spectacular artistic tradition inspired by The Tale of Genji, a monument of world literature created in the early eleventh century, and traces the evolution and reception of its imagery through the following ten centuries. The author, the noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu, centered her narrative on the “radiant Genji” (hikaru Genji), the son of an emperor who is demoted to commoner status and is therefore disqualified from ever ascending the throne. With an insatiable desire to recover his lost standing, Genji seeks out countless amorous encounters with women who might help him revive his imperial lineage. Readers have long reveled in the amusing accounts of Genji’s romantic liaisons and in the dazzling descriptions of the courtly splendor of the Heian period (794–1185). The tale has been equally appreciated, however, as social and political commentary, aesthetic theory, Buddhist philosophy, a behavioral guide, and a source of insight into human nature. Offering much more than romance, The Tale of Genji proved meaningful not only for men and women of the aristocracy but also for Buddhist adherents and institutions, military leaders and their families, and merchants and townspeople. The galleries that follow present the full spectrum of Genji-related works of art created for diverse patrons by the most accomplished Japanese artists of the past millennium. The exhibition also sheds new light on the tale’s author and her female characters, and on the women readers, artists, calligraphers, and commentators who played a crucial role in ensuring the continued relevance of this classic text. The manuscripts, paintings, calligraphy, and decorative arts on display demonstrate sophisticated and surprising interpretations of the story that promise to enrich our understanding of Murasaki’s tale today. -

2013-14 Annual Report

East Asian Studies Program and Department Annual Report 2013-2014 Table of Contents Director’s Letter .....................................................................................................................................................................1 Department and Program News .............................................................................................................................................3 Department and Program News ........................................................................................................................................3 Departures .........................................................................................................................................................................4 Language Programs ...........................................................................................................................................................5 Thesis Prizes ......................................................................................................................................................................6 EAS Department Majors .................................................................................................................................................. 6 EAS Language and Culture Certificate Students ..............................................................................................................7 EAS Program Certificate Students ....................................................................................................................................7 -

Faith and Power in Japanese Buddhist Art, 1600-2005

japanese art | religions graham FAITH AND POWER IN JAPANESE BUDDHIST ART, 1600–2005 Faith and Power in Japanese Buddhist Art explores the transformation of Buddhism from the premodern to the contemporary era in Japan and the central role its visual culture has played in this transformation. The chapters elucidate the thread of change over time in the practice of Bud- dhism as revealed in sites of devotion and in imagery representing the FAITH AND POWER religion’s most popular deities and religious practices. It also introduces the work of modern and contemporary artists who are not generally as- sociated with institutional Buddhism but whose faith inspires their art. IN JAPANESE BUDDHIST ART The author makes a persuasive argument that the neglect of these ma- terials by scholars results from erroneous presumptions about the aes- thetic superiority of early Japanese Buddhist artifacts and an asserted 160 0 – 20 05 decline in the institutional power of the religion after the sixteenth century. She demonstrates that recent works constitute a significant contribution to the history of Japanese art and architecture, providing evidence of Buddhism’s persistent and compelling presence at all levels of Japanese society. The book is divided into two chronological sections. The first explores Buddhism in an earlier period of Japanese art (1600–1868), emphasiz- ing the production of Buddhist temples and imagery within the larger political, social, and economic concerns of the time. The second section addresses Buddhism’s visual culture in modern Japan (1868–2005), specifically the relationship between Buddhist institutions prior to World War II and the increasingly militaristic national government that had initially persecuted them. -

Packery Channel Restoration Still on Hold

Inside the Moon Sandcastle Run A2 Biz Briefs A3 Stuff I Heard A5 Fishing A11 Issue 894 The 27° 37' 0.5952'' N | 97° 13' 21.4068'' W Island Free The voiceMoon of The Island since 1996 June 3, 2021 Weekly www.islandmoon.com FREE Photo by Evelyn Pless-Schuberth Around The Island Memorial Day From the Air Return By Dale Rankin The consensus among long-time of the Islanders seems to be that we have never seen as many people on our beaches as we saw last weekend. When the weather broke the crowds Litter turned out in a hurry and the driving conditions on the beach south of Beach Access Road 6 meant that very few beachgoers to could make their Critter! View Sunday looking north toward Newport Pass way down there. For a while Sunday View from Newport Pass looking south, Packery The return of the long-gone Litter afternoon the beach there looked from Packery Channel. Channel Jetties are at the top of the photo. Critter is at hand! like a used car lot as a long line of vehicles were stuck in the soft sand. The inability of drivers to use that part of the beach pushed everyone north packing the beaches there. There have been ongoing discussions for years about removing vehicles from the beach along the Michael J. Ellis Seawall but last weekend there would have been nowhere to park them except on Windward. There The City of Corpus Christi is renewed talk at city hall about announced Wednesday that The the need for a beach renourishment Critter will arrive on Padre Island on project to widen the beach but the Saturday, June 5 and to Flour Bluff problem is that the consultants hired July 10. -

Shibuya City 渋

渋谷区 Shibuya City Chapter 1 1Shibuya City Urban Characteristics Shibuya City Urban Characteristics and Roles The Present In consideration of plans for the industry and tourism sectors to make Shibuya City a mature, international city, it is important to first identify its current urban characteristics. With this in mind, the Japan Power Cities index (Mori Memorial Foundation) was used for analysis. Japan Power Cities analyzes the main cities 1 of Japan including the 23 wards of Tokyo in the six functions of city power The Present of Shibuya City (Economy & Business, Research and Development, Cultural Interaction, Daily Life & Livability, Environment, and Accessibility) and 83 indicators identifying the Industry and Tourism strengths and weaknesses of cities. In the total score for the 23 wards of Tokyo, the survey ranks Shibuya City in fifth place overall, fourth place in the functions of Economy & Business, Cultural Interaction, and Accessibility, and fifth place in Daily Life & Livability, whereas it ranks low in ninth place for Research & Development (see figure at top and table at bottom of p. 9). Furthermore, when narrowing down the viewpoints for industry and tourism and looking at the deviation scores in each indicator group, groups such as Business Vitality, Business Environment, and Financial Affairs in Economy & Business are ranked highly as shown in the figure on the top of page ten. Even among these areas, indicators such as Ratio of New Businesses and Density of Flexible Workplaces are strong (see table on bottom of p. 10). Also, as shown in the figure in the middle of page ten, in Cultural Interaction, groups such as Volume of Interaction, Volume of Communication, and Intangible Resources are strengths.