Saki / H.H. Munro 1870-1916 Bios

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll With 42 Illustrations by John Tenniel All in the golden afternoon Full leisurely we glide ; For both our oars, with little skill, By little arms are plied, While little hands make vain pretence Our wanderings to guide. Ah, cruel Three ! In such an hour, Beneath such dreamy weather, To beg a tale of breath too weak To stir the tiniest feather ! Yet what can one poor voice avail Against three tongues together ? Imperious Prima flashes forth Her edict “ to begin it” : In gentler tones Secunda hopes “ There will be nonsense in it ! ” While Tertia interrupts the tale Not more than once a minute. Anon, to sudden silence won, In fancy they pursue The dream-child moving through a land Of wonders wild and new, In friendly chat with bird or beast— And half believe it true. And ever, as the story drained The wells of fancy dry, And faintly strove that weary one To put the subject by, “ The rest next time—” “ It is next time ! ” The happy voices cry. Thus grew the tale of Wonderland : Thus slowly, one by one, Its quaint events were hammered out— And now the tale is done, And home we steer, a merry crew, Beneath the setting sun. Alice ! A childish story take, And, with a gentle hand, Lay it where Childhood’s dreams are twined In Memory’s mystic band, Like pilgrim’s wither’d wreath of flowers Pluck’d in a far-off land. CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I Down the Rabbit-Hole 7 II The Pool of Tears 14 III A Caucus-Race and a Long Tale 22 IV The Rabbit Sends in a Little Bill 29 V Advice from a Caterpillar 38 VI Pig -

Read Book the Westminster Alice : a Political Parody Based on Lewis Carrolls Wonderland

THE WESTMINSTER ALICE : A POLITICAL PARODY BASED ON LEWIS CARROLLS WONDERLAND Author: Hector Hugh Munro (Saki) Number of Pages: 98 pages Published Date: 01 Aug 2010 Publisher: Evertype Publication Country: United Kingdom Language: English ISBN: 9781904808541 DOWNLOAD: THE WESTMINSTER ALICE : A POLITICAL PARODY BASED ON LEWIS CARROLLS WONDERLAND The Westminster Alice : A Political Parody Based on Lewis Carrolls Wonderland PDF Book Starratt's focus on leadership as human resource development will energize the efforts of faculty, staff, and students to improve the quality of learning-the primary work of schools. This will enable me to give more time to the discussion of those methods, the utility of which is still an open question. You'll find yourself basking in God's love while giving it away. No matter what your background is, this book will enable you to master Excel 2016's most advanced features. To this end they have gathered together a distinguished group of economists, sociologists, political scientists, and organization, innovation and institutional theorists to both assess current research on innovation, and to set out a new research agenda. She then traveled to Manhattan to attend Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons. Visit GiftOfLogic. But the policy changes made between 2007 and 2010 will likely constrain any new initiatives in the future. Then,afteratwo-weekelectronic discussion, the Programme Committee selected 33 papers for presentation at the conference. (New Scientist) The book certainly merits its acceptance as essential reading for postgraduates and will be valuable to anyone associated in any way with research or with presentation of technical or scientific information of any kind. -

"Animals in Saki's Short Stories Within the Context of Imperialism: a Non

Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of English Language and Literature ANIMALS IN SAKI’S SHORT STORIES WITHIN THE CONTEXT OF IMPERIALISM: A NON-ANTHROPOCENTRIC APPROACH Adem Balcı Master’s Thesis Ankara, 2014 ANIMALS IN SAKI’S SHORT STORIES WITHIN THE CONTEXT OF IMPERIALISM: A NON-ANTHROPOCENTRIC APPROACH Adem Balcı Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of English Language and Literature Master’s Thesis Ankara, 2014 iii To my family iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to my supervisor Assist. Prof. Dr. Sinan AKILLI for his encouragement, friendship, and academic guidance. Without his never-ending support, encouragement, constructive criticism, unwavering belief in me, unending patience, genuine kindness, suggestions, meticulous feedbacks and comments, this thesis would not be what it is now. I would also like to express my deepest gratitude to Prof. Dr. Burçin EROL, the Head of the Department of English Language and Literature, for her endless support, warm welcome, motivation and encouragement whenever I needed. I wish to express my sincere gratitude to the distinguished members of the Examining Committee who contributed to this thesis through their constructive comments and meticulous feedback. Firstly, I would like to thank Prof. Dr. Deniz BOZER for her suggestions, invaluable comments, and academic guidance in each step of this thesis. I would also like to thank Prof. Dr. Serpil OPPERMANN wholeheartedly for introducing me to the posthumanities and animal studies, for helping me to write my thesis proposal and finally for her contribution to the development of this thesis with her invaluable comments, her books, and feedbacks. -

In Commemoration of Hector Munro, 'Saki' Transcript

The grinning shadow that sat at the feast: In commemoration of Hector Munro, 'Saki' Transcript Date: Tuesday, 14 November 2006 - 12:00AM The Grinning Shadow that sat at the Feast: an appreciation of the life and work of Hector Munro 'Saki' Professor Tim Connell Hector Munro was a man of many parts, and although he died relatively young, he lived through a time of considerable change, had a number of quite separate careers and a very broad range of interests. He was also a competent linguist who spoke Russian, German and French. Today is the 90th anniversary of his death in action on the Somme, and I would like to review his importance not only as a writer but also as a figure in his own time. Early years to c.1902 Like so many Victorians, he was born into a family with a long record of colonial service, and it is quite confusing to see how many Hector Munros there are with a military or colonial background. Our Hector’s most famous ancestor is commemorated in a well-known piece at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Tippoo's Tiger shows a man being eaten by a mechanical tiger and the machine emits both roaring and groaning sounds. 1 Hector's grandfather was an Admiral, and his father was in the Burma Police. The family was hit by tragedy when Hector's mother was killed in a bizarre accident involving a runaway cow. It is curious that strange events involving animals should form such a common feature of Hector's writing 2 but this may also derive from his upbringing in the Devonshire countryside and a home that was dominated by the two strangest creatures of all - Aunt Augusta and Aunt Tom. -

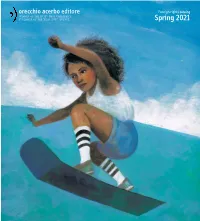

Orecchio Acerbo Rights List Spring 2021

orecchio acerbo editore Foreign rights catalog Winner of the BoP · Best Children’s PuBlisher of the Year 2017, euroPe Spring 2021 picture books daybrEak NEW by Daniel Fehr illustrations Elena Rotondo for children 4 years and older pp. 28 | cm. 23 x 21 ISBN 9788832070651 | July 2021 today NEW by Daniel Fehr big quEstioNs | grEat advENturEs illustrations Simone Rea WaitiNg for Walt for children 4 years and older by Daniel Fehr The story is about a young boy and his father. pp. 64 | cm. 17 x 24 illustrations Maja Celjia In the middle of the night they leave their house. ISBN 9788832070590 | April 2021 for children 5 years and older For the boy it is the first time that he leaves home pp. 32 | cm. 24 x 32 | May 2020 at this time of the night when normally uNdEr thE gazE of timE | rEcouNtiNg thE prEsENt he is asleep. As they walk through the forest storiEs of thE visioNary aNd thE absurd laughtEr aNd smilEs the flashlight of the boy “turns on” part A father who is leaving. Two brothers. A long wait. of the vegetation and at the same time the rest But together it is easier, together it is easy disappear. He turns off the flashlight and “turns on” to be strong. The older brother reads books Two kids are waiting for Walt. But who is Walt? all his senses: he experiences the darkness, to the younger one who can’t read yet but can And, if Walt was there with them, what would the sounds of the forest, the sound of his father, at least choose the book; then they go together they all do together? They would have a lot the roughness of the ground, the smells… on a secret mission: is every mission of spies of fun, because when he is there he always He dares not ask for the space and time secret? Then one goes to play football, the other has crazy ideas. -

AUDIOBOOKS Alice in Wonderland Around the World in 80 Days at the Back of the North Wind Birthday of the Enfanter Blue Cup Cruis

AUDIOBOOKS Alice In Wonderland Around the World in 80 days At the Back of the North Wind Birthday of the Enfanter Blue Cup Cruise of the Dazzler Devoted Friend Dragon Farm Dragons - Dreadful Dragon of Hay Hill Dragons - Kind Little Edmund Dragons - Reluctant Dragon Dragons - Snap-Dragons Dragons - The Book of Beasts Dragons - The Deliverers of Their Country Dragons - The Dragon Tamers Dragons - The Fiery Dragon Dragons - The Ice Dragon Dragons - The Isle of the Nine Whirlpools Dragons - The Last of The Dragons Dragons - Two Dragons Dragons - Uncle James Eric Prince of Lorlonia Ernest Fluffy Rabbit Faerie Queene Fifty Stories from UNCLE REMUS Fisherman and his Soul Fisherman and The Goldfish Five Children and It Gentle Alice Brown Ghost of Dorothy Dingley Goblin Market Godmother's Garden Gullivers Travels 1 - A Voyage to Lilliput Gullivers Travels 2 - A Voyage to Brobdingnag Gullivers Travels 3 A Voyage to Laputa, Balnibarbi, Luggnagg, Glubbdubdrib, and Japan Gullivers Travels 4 A Voyage to the Country of the Houynhnms Hammond's Hard Lines Happy Prince Her Majesty's Servants Horror of the Heights How I Killed a Bear Huckleberry Finn Hunting of The Snark King of The Golden River Knock Three Times Lair of The White Worm Little Boy Lost Little Round House Loaded Dog Lukundoo Lull Magic Lamplighter Malchish Kibalchish Malcolm Sage Detective Man and Snake Martin Rattler Moon Metal Moonraker Mowgli Mr Papingay's Flying Shop Mr Papingay's Ship New Sun Nightingale and Rose Nutcracker OZ 01 - Wizard of Oz OZ 02 - The Land of Oz OZ 03 - Ozma of Oz -

English Literature, History, Children's Books And

LONDON 13 DECEMBER 2016 DECEMBER 13 LONDON HISTORY, CHILDREN’S CHILDREN’S HISTORY, ENGLISH LITERATURE, ENGLISH LITERATURE, BOOKS AND BOOKS ILLUSTRATIONS LONDON ENGLISH LITERATURE, HISTORY, CHILDREN’S BOOKS AND ILLUSTRATIONS 13 DECEMBER 2016 L16408 ENGLISH LITERATURE, HISTORY, CHILDREN’S BOOKS AND ILLUSTRATIONS FRONT COVER LOT 67 (DETAIL) BACK COVER LOT 317 THIS PAGE LOT 30 (DETAIL) ENGLISH LITERATURE, HISTORY, CHILDREN’S BOOKS AND ILLUSTRATIONS AUCTION IN LONDON 13 DECEMBER 2016 SALE L16408 SESSION ONE: 10 AM SESSION TWO: 2.30 PM EXHIBITION Friday 9 December 9 am-4.30 pm Saturday 10 December 12 noon-5 pm Sunday 11 December 12 noon-5 pm Monday 12 December 9 am-7 pm 34-35 New Bond Street London, W1A 2AA +44 (0)20 7293 5000 sothebys.com THIS PAGE LOT 101 (DETAIL) SPECIALISTS AND AUCTION ENQUIRIES For further information on lots in this auction please contact any of the specialists listed below. SALE NUMBER SALE ADMINISTRATOR L16408 “BABBITTY” Lukas Baumann [email protected] BIDS DEPARTMENT +44 (0)20 7293 5287 +44 (0)20 7293 5283 fax +44 (0)20 7293 5904 fax +44 (0)20 7293 6255 [email protected] POST SALE SERVICES Kristy Robinson Telephone bid requests should Post Sale Manager Peter Selley Dr. Philip W. Errington be received 24 hours prior FOR PAYMENT, DELIVERY Specialist Specialist to the sale. This service is AND COLLECTION +44 (0)20 7293 5295 +44 (0)20 7293 5302 offered for lots with a low estimate +44 (0)20 7293 5220 [email protected] [email protected] of £2,000 and above. -

The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, the Hunting of the Snark, a Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) Online

yaTOs (Download pdf) The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) Online [yaTOs.ebook] The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) Pdf Free Lewis Carroll ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1419651 in Books 2011-11-07Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 1.70 x 6.50 x 9.30l, 1.70 #File Name: 0890097003440 pages | File size: 46.Mb Lewis Carroll : The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters): 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Wonderful books for a wonderful priceBy llamapyrLewis Carroll must've been the greatest children's book author of his time. I really admire his writing style and the creativity of his books, having grown up on them since I was 6. I've got a bunch of his novels in hardcover and paperback sitting on my shelves, so it seemed only right to add some digital versions to my library :)Anyway, I came here looking for Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass and found this set, and for a mere 99 cents it seemed worth a look. -

ARTICLE: Jan Susina: Playing Around in Lewis Carroll's Alice Books

Playing Around in Lewis Carroll’s Alice Books • Jan Susina Mathematician Charles Dodgson’s love of play and his need for rules came together in his use of popular games as part of the structure of the two famous children’s books, Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, he wrote under the pseudonym Lewis Carroll. The author of this article looks at the interplay between the playing of such games as croquet and cards and the characters and events of the novels and argues that, when reading Carroll (who took a playful approach even in his academic texts), it is helpful to understand games and game play. Charles Dodgson, more widely known by his pseudonym Lewis Carroll, is perhaps one of the more playful authors of children’s literature. In his career, as a children’s author and as an academic logician and mathematician, and in his personal life, Carroll was obsessed with games and with various forms of play. While some readers are surprised by the seemingly split personality of Charles Dodgson, the serious mathematician, and Lewis Carroll, the imaginative author of children’s books, it was his love of play and games and his need to establish rules and guidelines that effectively govern play that unite these two seemingly disparate facets of Carroll’s personality. Carroll’s two best-known children’s books—Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking- Glass and What Alice Found There (1871)—use popular games as part of their structure. In Victoria through the Looking-Glass, Florence Becker Lennon has gone so far as to suggest about Carroll that “his life was a game, even his logic, his mathematics, and his singular ordering of his household and other affairs. -

Beasts and Super-Beasts: by Saki Online

j1Zfo [E-BOOK] Beasts and Super-Beasts: by Saki Online [j1Zfo.ebook] Beasts and Super-Beasts: by Saki Pdf Free Saki Saki *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook 2017-01-07 2017-01-07File Name: B01NBSEDIW | File size: 52.Mb Saki Saki : Beasts and Super-Beasts: by Saki before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Beasts and Super-Beasts: by Saki: 5 of 5 people found the following review helpful. Saki at his bestBy Robert GuttmanBeasts and Super-Beasts comprises thirty-seven short stories from the pen of the incomparable Saki, which was the pen-name for H. H. Munro. Saki's ironic and witty stories chronicled the British upper class during the Edwardian period, the era that represented the zenith of British power and complacency just before the cataclysm of World War I. The quality of his wit and satiric humor are of the very highest order, comparable to very best of Oscar Wilde and Ambrose Bierce. As with Bierce, a touch of cruelty was often present in Saki's humor. In addition, Saki also shared with Bierce a taste for the supernatural, a quality which comes across in many of the stories in this particular collection.Reading Saki is an absolute must for any aspiring writer, and an absolute pleasure for readers everywhere.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Gotta love Saki!By Kevin BeachyIf you like Mark Twain's particular strain of sarcastic humor, you gotta try Saki. -

Lewis Carroll 'The Jabberwocky'

Lewis Carroll ‘The Jabberwocky’ 'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe; All mimsy were the borogoves, And the mome raths outgrabe. "Beware the Jabberwock, my son The jaws that bite, the claws that catch! Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun The frumious Bandersnatch!" He took his vorpal sword in hand; Long time the manxome foe he sought— So rested he by the Tumtum tree, And stood awhile in thought. And, as in uffish thought he stood, The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame, Came whiffling through the tulgey wood, And burbled as it came! One, two! One, two! And through and through The vorpal blade went snicker-snack! He left it dead, and with its head He went galumphing back. "And hast thou slain the Jabberwock? Come to my arms, my beamish boy! O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay!" He chortled in his joy. 'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe; All mimsy were the borogoves, And the mome raths outgrabe. Rudyard Kipling ‘The Way Through The Woods’ They shut the road through the woods Seventy years ago. W eather and rain have undone it again, And now you would never know There was once a road through the woods Before they planted the trees. It is underneath the coppice and heath And the thin anemones. Only the keeper sees That, where the ring-dove broods, And the badgers roll at ease, There was once a road through the woods. Yet, if you enter the woods Of a summer evening late, When the night-air cools on the trout-ringed pools Where the otter whistles his mate, (They fear not men in the woods, Because they see so few) You will hear the beat of a horse’s feet, And the swish of a skirt in the dew, Steadily cantering through The misty solitudes, As though they perfectly knew The old lost road through the woods… But there is no road through the woods. -

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

digital edition to that of the The world’s original. After weeks of toil he most precise created an exact replica of the A LICE’S original! The book was added replica to VolumeOne’s print-on- Adventures in Wonderland demand offering. While a PDF of the world’s version is offered on various portals of the Net, BookVirtual most famous took the project to heart and children’s book! added its interface designs and programming. Welcome to the world’s most precise all-digital In 1998, Peter Zelchenko replica of the world’s most began a project for Volume- famous children’s book. Thank One Publishing: to create an you, Peter. exact digital replica of Lewis Carroll’s first edition of Alice. BookVirtual™ Working with the original Books made Virtual. Books made well. 1865 edition and numerous www.bookvirtual.com other editions at the Newberry Library in Chicago, Zelchenko created a digital masterpiece in his own right, a testament to NAVIGATE the original work of Lewis Carroll (aka Prof. Charles Dodgson) who personally CONTROL directed the typography for the first Alice. CLOSE THE BOOK After much analyis, Peter then painstakingly matched letter to letter, line to line, of his new TURN THE PAGE BY LEWIS CARROLL ILLUSTRATED BY JOHN TENNIEL RABBIT-HOLE. 1 Fit Page Full Screen On/Off Close Book ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND Navigate Control Internet Digital InterfaceInterface by byBookVirtual BookVirtual Corp. Corp. U.S. U.S. Patent Patent Pending. Pending. © 2000' 2000 All AllRights Rights Reserved. Reserved. Fit Page Full Screen On/Off Close Book ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND BY LEWIS CARROLL WITH FORTY-TWO ILLUSTRATIONS BY JOHN TENNIEL VolumeOne Publishing Chicago, Illinois 1998 A BookVirtual Digital Edition, v.1.2 November, 2000 Navigate Control Internet Digital Interface by BookVirtual Corp.