ARTICLE: Jan Susina: Playing Around in Lewis Carroll's Alice Books

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll With 42 Illustrations by John Tenniel All in the golden afternoon Full leisurely we glide ; For both our oars, with little skill, By little arms are plied, While little hands make vain pretence Our wanderings to guide. Ah, cruel Three ! In such an hour, Beneath such dreamy weather, To beg a tale of breath too weak To stir the tiniest feather ! Yet what can one poor voice avail Against three tongues together ? Imperious Prima flashes forth Her edict “ to begin it” : In gentler tones Secunda hopes “ There will be nonsense in it ! ” While Tertia interrupts the tale Not more than once a minute. Anon, to sudden silence won, In fancy they pursue The dream-child moving through a land Of wonders wild and new, In friendly chat with bird or beast— And half believe it true. And ever, as the story drained The wells of fancy dry, And faintly strove that weary one To put the subject by, “ The rest next time—” “ It is next time ! ” The happy voices cry. Thus grew the tale of Wonderland : Thus slowly, one by one, Its quaint events were hammered out— And now the tale is done, And home we steer, a merry crew, Beneath the setting sun. Alice ! A childish story take, And, with a gentle hand, Lay it where Childhood’s dreams are twined In Memory’s mystic band, Like pilgrim’s wither’d wreath of flowers Pluck’d in a far-off land. CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I Down the Rabbit-Hole 7 II The Pool of Tears 14 III A Caucus-Race and a Long Tale 22 IV The Rabbit Sends in a Little Bill 29 V Advice from a Caterpillar 38 VI Pig -

Open Maryallenfinal Thesis.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH SIX IMPOSSIBLE THINGS BEFORE BREAKFAST: THE LIFE AND MIND OF LEWIS CARROLL IN THE AGE OF ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND MARY ALLEN SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in English with honors in English Reviewed and approved* by the following: Kate Rosenberg Assistant Teaching Professor of English Thesis Supervisor Christopher Reed Distinguished Professor of English, Visual Culture, and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Honors Adviser * Electronic approvals are on file. i ABSTRACT This thesis analyzes and offers connections between esteemed children’s literature author Lewis Carroll and the quality of mental state in which he was perceived by the public. Due to the imaginative nature of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, it has been commonplace among scholars, students, readers, and most individuals familiar with the novel to wonder about the motive behind the unique perspective, or if the motive was ever intentional. This thesis explores the intentionality, or lack thereof, of the motives behind the novel along with elements of a close reading of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. It additionally explores the origins of the concept of childhood along with the qualifications in relation to time period, culture, location, and age. It identifies common stereotypes and presumptions within the subject of mental illness. It aims to achieve a connection between the contents of Carroll’s novel with -

Children's Books & Illustrated Books

CHILDREN’S BOOKS & ILLUSTRATED BOOKS ALEPH-BET BOOKS, INC. 85 OLD MILL RIVER RD. POUND RIDGE, NY 10576 (914) 764 - 7410 CATALOGUE 94 ALEPH - BET BOOKS - TERMS OF SALE Helen and Marc Younger 85 Old Mill River Rd. Pound Ridge, NY 10576 phone 914-764-7410 fax 914-764-1356 www.alephbet.com Email - [email protected] POSTAGE: UNITED STATES. 1st book $8.00, $2.00 for each additional book. OVERSEAS shipped by air at cost. PAYMENTS: Due with order. Libraries and those known to us will be billed. PHONE orders 9am to 10pm e.s.t. Phone Machine orders are secure. CREDIT CARDS: VISA, Mastercard, American Express. Please provide billing address. RETURNS - Returnable for any reason within 1 week of receipt for refund less shipping costs provided prior notice is received and items are shipped fastest method insured VISITS welcome by appointment. We are 1 hour north of New York City near New Canaan, CT. Our full stock of 8000 collectible and rare books is on view and available. Not all of our stock is on our web site COVER ILLUSTRATION - #307 - ORIGINAL ART BY MAUD HUMPHREY FOR GALLANT LITTLE PATRIOTS #357 - Meggendorfer Das Puppenhaus (The Doll House) #357 - Meggendorfer Das Puppenhaus #195 - Detmold Arabian Nights #526 - Dr. Seuss original art #326 - Dorothy Lathrop drawing - Kou Hsiung (Pekingese) #265 - The Magic Cube - 19th century (ca. 1840) educational game Helen & Marc Younger Pg 3 [email protected] THE ITEMS IN THIS CATALOGUE WILL NOT BE ON RARE TUCK RAG “BLACK” ABC 5. ABC. (BLACK) MY HONEY OUR WEB SITE FOR A FEW WEEKS. -

THE LAND BEYOND the MAGIC MIRROR by E

GREYHAWK CASTLE DUNGEON MODULE EX2 THE LAND BEYOND THE MAGIC MIRROR by E. Gary Gygax AN ADVENTURE IN A WONDROUS PLACE FOR CHARACTER LEVELS 9-12 No matter the skill and experience of your party, they will find themselves dazed and challenged when they pass into The Land Beyond the Magic Mirror! Distributed to the book trade in the United States by Random House, Inc. and in Canada by Random House of Canada Ltd. Distributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. Distributed in the United Kingdom by TSR Hobbies (UK) Ltd. AD&D and WORLD OF GREYHAWK are registered trademarks owned by TSR Hobbies, Inc. ©1983 TSR Hobbies, Inc. All Rights Reserved. TSR Hobbies, Inc. TSR Hobbies (UK) Ltd. POB 756 The Mill, Rathmore Road Lake Geneva, Cambridge CB14AD United Kingdom Printed in U.S.A. WI 53147 ISBN O 88038-025-X 9073 TABLE OF CONTENTS This module is the companion to Dungeonland and was originally part of the Greyhawk Castle dungeon complex. lt is designed so that it can be added to Dungeonland, used alone, or made part of virtually any campaign. It has an “EX” DUNGEON MASTERS PREFACE ...................... 2 designation to indicate that it is an extension of a regular THE LAND BEYOND THE MAGIC MIRROR ............. 4 dungeon level—in the case of this module, a far-removed .................... extension where all adventuring takes place on another plane The Magic Mirror House First Floor 4 of existence that is quite unusual, even for a typical AD&D™ The Cellar ......................................... 6 Second Floor ...................................... 7 universe. This particular scenario has been a consistent ......................................... -

Alice in Wonderland

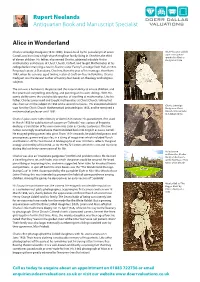

Rupert Neelands Antiquarian Book and Manuscript Specialist Alice in Wonderland Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (1832-1898), known to all by his pseudonym of Lewis Alice Pleasance Liddell, Carroll, was born into a high-church Anglican family living in Cheshire, the third aged seven, photo- graphed by Charles of eleven children. His father, also named Charles, obtained a double first in Dodgson in 1860 mathematics and classics at Christ Church, Oxford, and taught Mathematics at his college before marrying a cousin, Frances Jane “Fanny” Lutwidge from Hull, in 1827. Perpetual curate at Daresbury, Cheshire, from the year of his marriage, then from 1843, when his son was aged twelve, rector at Croft-on-Tees in Yorkshire, Charles Dodgson was the devout author of twenty-four books on theology and religious subjects. The son was a humourist. He possessed the natural ability to amuse children, and first practised storytelling, versifying, and punning on his own siblings. With this comic ability came the unshakeable gravitas of excelling at mathematics. Like his father, Charles junior read and taught mathematics at Christ Church, taking first class honours in the subject in 1854 and a second in classics. His exceptional talent Charles Lutwidge won him the Christ Church Mathematical Lectureship in 1855, and he remained a Dodgson at Christ mathematical professor until 1881. Church 1856-60 (John Rich Album, NPG) Charles’s jokes were rather literary or donnish in nature. His pseudonym, first used in March 1856 for publication of a poem on “Solitude”, was a piece of linguistic drollery, a translation of his own name into Latin as Carolus Ludovicus. -

Humpty Dumpty's Explanation

Humpty Dumpty’s Explanation Humpty Dumpty’s explanation of the first verse of Jabberwocky from Through the Looking Glass and Alice’s Adventures there. 'You seem very clever at explaining words, Sir,' said Alice. 'Would you kindly tell me the meaning of the poem called "Jabberwocky"?' 'Let's hear it,' said Humpty Dumpty. 'I can explain all the poems that were ever invented--and a good many that haven't been invented just yet.' This sounded very hopeful, so Alice repeated the first verse: 'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe; All mimsy were the borogoves, And the mome raths outgrabe. 'That's enough to begin with,' Humpty Dumpty interrupted: 'there are plenty of hard words there. "BRILLIG" means four o'clock in the afternoon--the time when you begin BROILING things for dinner.' 'That'll do very well,' said Alice: and "SLITHY"?' 'Well, "SLITHY" means "lithe and slimy." "Lithe" is the same as "active." You see it's like a portmanteau--there are two meanings packed up into one word.' 'I see it now,' Alice remarked thoughtfully: 'and what are "TOVES"?' 'Well, "TOVES" are something like badgers--they're something like lizards--and they're something like corkscrews.' 'They must be very curious looking creatures.' 'They are that,' said Humpty Dumpty: 'also they make their nests under sun-dials--also they live on cheese.' 'Andy what's the "GYRE" and to "GIMBLE"?' 'To "GYRE" is to go round and round like a gyroscope. To "GIMBLE" is to make holes like a gimlet.' 1 'And "THE WABE" is the grass-plot round a sun-dial, I suppose?' said Alice, surprised at her own ingenuity. -

Saki / H.H. Munro 1870-1916 Bios

Saki / H.H. Munro 1870-1916 Bios http://www.litgothic.com/Authors/saki.html Up to now, little has been known about Hector Hugh Munro except that he used the pen name “Saki”; that he wrote a number of witty short stories, two novels, several plays, and a history of Russia; and that he was killed in World War I. His friend Rothay Reynolds published “A Memoir of H. H. Munro” in Saki’s The Toys of Peace (1919), and Munro’s sister Ethel furnished a brief “Biography of Saki” for a posthumous collection of his work entitled The Square Egg and Other Sketches (1924). A. J. Langguth’s Saki is the first full-length biography of the man who, during his brief writing career, published a succession of bright, satirical, and sometimes perfectly crafted short stories that have entertained and amused readers in many countries for well over a half-century. Hector Munro was the third child of Charles Augustus Munro, a British police officer in Burma, and his wife Mary Frances. The children were all born in Burma. Pregnant with her fourth child, Mrs. Munro was brought with the children to live with her husband’s family in England until the child arrived. Frightened by the charge of a runaway cow on a country lane, Mrs. Munro died after a miscarriage. Since the widowed father had to return to Burma, the children — Charles, Ethel, and Hector — were left with their Munro grandmother and her two dominating and mutually antagonistic spinster daughters, Charlotte (“Aunt Tom”) and Augusta. This situation would years later provide incidents, characters, and themes for a number of Hector Munro’s short stories as well as this epitaph for Augusta by Ethel: “A woman of ungovernable temper, of fierce likes and dislikes, imperious, a moral coward, possessing no brains worth speaking of, and a primitive disposition. -

ALICE's ADVENTURES in WONDERLAND Lewis Carroll

The Jefferson Performing Arts Society Presents 1118 Clearview Parkway Metairie, LA 70001 504-885-2000 www.jpas.org 1 | P a g e Table of Contents Teacher’s Notes………………………..…………..…………..……..3 Standards and Benchmarks…………………..……………….…..5 Background………………………………………..…….………………6 Alice’s Adventures, Comparing and Contrasting ………… 12 Art, Math and Set Design: Alice in Minecraft Land...................................................33 The Science of Color Meets the White Rabbit and the March Hare...................74 Additional Resources…………………………………..…..….….106 2 | P a g e Teacher’s Notes Music and Lyrics by Sammy Fain and Bob Hilliard, Oliver Wallace and Cy Coban, Allie Wrubel and Ray Gilbert, Mack David, Al Hoffman and Jerry Livingston Music Adapted and Arranged and Additional Music and Lyrics by Bryan Louiselle Book Adapted and Additional Lyrics by David Simpatico Based on the 1951 Disney film, Alice in Wonderland, and the Lewis Carroll novels, "The Adventures of Alice in Wonderland" and "Through the Looking Glass," Lewis Carroll's famous heroine comes to life in this delightful adaptation of the classic Disney film. Lewis Carroll was the nom de plume of Charles L. Dodgson. Born on January 27, 1832 in Daresbury, Cheshire, England, Charles Dodgson wrote and created games as a child. At age 20 he received a studentship at Christ Church and was appointed a lecturer in mathematics. Dodgson was shy but enjoyed creating stories for children. Within the academic discipline of mathematics, Dodgson worked primarily in the fields of geometry, linear and matrix algebra, mathematical logic, and recreational mathematics, producing nearly a dozen books under his real name. Dodgson also developed new ideas in linear algebra (e.g., the first printed proof of the Kronecker-Capelli theorem,) probability, and the study of elections (e.g., Dodgson's method); some of this work was not published until well after his death. -

In Commemoration of Hector Munro, 'Saki' Transcript

The grinning shadow that sat at the feast: In commemoration of Hector Munro, 'Saki' Transcript Date: Tuesday, 14 November 2006 - 12:00AM The Grinning Shadow that sat at the Feast: an appreciation of the life and work of Hector Munro 'Saki' Professor Tim Connell Hector Munro was a man of many parts, and although he died relatively young, he lived through a time of considerable change, had a number of quite separate careers and a very broad range of interests. He was also a competent linguist who spoke Russian, German and French. Today is the 90th anniversary of his death in action on the Somme, and I would like to review his importance not only as a writer but also as a figure in his own time. Early years to c.1902 Like so many Victorians, he was born into a family with a long record of colonial service, and it is quite confusing to see how many Hector Munros there are with a military or colonial background. Our Hector’s most famous ancestor is commemorated in a well-known piece at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Tippoo's Tiger shows a man being eaten by a mechanical tiger and the machine emits both roaring and groaning sounds. 1 Hector's grandfather was an Admiral, and his father was in the Burma Police. The family was hit by tragedy when Hector's mother was killed in a bizarre accident involving a runaway cow. It is curious that strange events involving animals should form such a common feature of Hector's writing 2 but this may also derive from his upbringing in the Devonshire countryside and a home that was dominated by the two strangest creatures of all - Aunt Augusta and Aunt Tom. -

The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, the Hunting of the Snark, a Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) Online

yaTOs (Download pdf) The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) Online [yaTOs.ebook] The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) Pdf Free Lewis Carroll ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1419651 in Books 2011-11-07Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 1.70 x 6.50 x 9.30l, 1.70 #File Name: 0890097003440 pages | File size: 46.Mb Lewis Carroll : The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters): 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Wonderful books for a wonderful priceBy llamapyrLewis Carroll must've been the greatest children's book author of his time. I really admire his writing style and the creativity of his books, having grown up on them since I was 6. I've got a bunch of his novels in hardcover and paperback sitting on my shelves, so it seemed only right to add some digital versions to my library :)Anyway, I came here looking for Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass and found this set, and for a mere 99 cents it seemed worth a look. -

Spilplus.Journals.Ac.Za

http://spilplus.journals.ac.za http://spilplus.journals.ac.za THE WORLD OF LANGUAGE 2 ITS BEHAVIOURAL BELT by Rudolf P. BOlha SPIL PLUS 25 1994 http://spilplus.journals.ac.za CONTENTS 2 Language behaviour 2.1 General nature: unobservable action 2 2.2 Specific properties 4 2.2.1 Purposiveness 4 2.2.2 Cooperativeness 13 2.2.3 Space-time anchoredness 16 2.2.4 Nonlinguistic embeddedness 18 2.2.5 Innovativeness 21 2.2.6 Stimulus-freedom 22 2.2.7 Appropriateness 24 2.2.8 Rule-governedness 25 2.3 Kinds of language behaviour 26 2.3.1 Forms of language behaviour 27 2.3.1.1 Producing utterances 28 2.3.1.2 Comprehending utterances 30 2.3.1.3 Judging utterances 32 2.3.2 Means of language behaviour 39 2.3.3 Modes of language behaviour 47 2.4 The bounds of language behaviour 51 Notes to Chapter 2 53 Bibliography 62 http://spilplus.journals.ac.za 1 2 Language behaviour In Carrollinian worlds, all sorts of creatures have the remarkable knack of appearing, as it were, from nowhere. For instance, soon after Alice had entered the world created by Gilbert Adair beyond a needle's eye, she witnessed how kittens and puppies, followed by cats and dogs, fell out of the sky: 'Hundreds of cats and dogs .... were pouring down as far as she could see. Once they landed, they would all make a rush for lower ground, gathering there in huddles --- "or puddles, I suppose one ought to say" --- .... ' [TNE 41] In Needle's Eye World, one could accordingly say It rained cats arui dogs, and mean it literally. -

The Other Side of the Lens-Exhibition Catalogue.Pdf

The Other Side of the Lens: Lewis Carroll and the Art of Photography during the 19th Century is curated by Edward Wakeling, Allan Chapman, Janet McMullin and Cristina Neagu and will be open from 4 July ('Alice's Day') to 30 September 2015. The main purpose of this new exhibition is to show the range and variety of photographs taken by Lewis Carroll (aka Charles Dodgson) from topography to still-life, from portraits of famous Victorians to his own family and wide circle of friends. Carroll spent nearly twenty-five years taking photographs, all using the wet-collodion process, from 1856 to 1880. The main sources of the photographs on display are Christ Church Library, the Metropolitan Museum, New York, National Portrait Gallery, London, Princeton University and the University of Texas at Austin. Visiting hours: Monday: 2:00 pm - 4.30 pm; Tuesday - Thursday: 10.00 am - 1.00 pm; 2:00 pm - 4.30 pm; Friday: 10:00 am - 1.00 pm. Framed photographs on loan from Edward Wakeling Photographic equipment on loan from Allan Chapman Exhibition catalogue and poster by Cristina Neagu 2 The Other Side of the Lens Lewis Carroll and the Art of Photography ‘A Tea Merchant’, 14 July 1873. IN 2155 (Texas). Tom Quad Rooftop Studio, Christ Church. Xie Kitchin dressed in a genuine Chinese costume sitting on tea-chests portraying a Chinese ‘tea merchant’. Dodgson subtitled this as ‘on duty’. In a paired image, she sits with hat off in ‘off duty’ pose. Contents Charles Lutwidge Dodgson and His Camera 5 Exhibition Catalogue Display Cases 17 Framed Photographs 22 Photographic Equipment 26 3 4 Croft Rectory, July 1856.