Open Maryallenfinal Thesis.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Children's Books & Illustrated Books

CHILDREN’S BOOKS & ILLUSTRATED BOOKS ALEPH-BET BOOKS, INC. 85 OLD MILL RIVER RD. POUND RIDGE, NY 10576 (914) 764 - 7410 CATALOGUE 94 ALEPH - BET BOOKS - TERMS OF SALE Helen and Marc Younger 85 Old Mill River Rd. Pound Ridge, NY 10576 phone 914-764-7410 fax 914-764-1356 www.alephbet.com Email - [email protected] POSTAGE: UNITED STATES. 1st book $8.00, $2.00 for each additional book. OVERSEAS shipped by air at cost. PAYMENTS: Due with order. Libraries and those known to us will be billed. PHONE orders 9am to 10pm e.s.t. Phone Machine orders are secure. CREDIT CARDS: VISA, Mastercard, American Express. Please provide billing address. RETURNS - Returnable for any reason within 1 week of receipt for refund less shipping costs provided prior notice is received and items are shipped fastest method insured VISITS welcome by appointment. We are 1 hour north of New York City near New Canaan, CT. Our full stock of 8000 collectible and rare books is on view and available. Not all of our stock is on our web site COVER ILLUSTRATION - #307 - ORIGINAL ART BY MAUD HUMPHREY FOR GALLANT LITTLE PATRIOTS #357 - Meggendorfer Das Puppenhaus (The Doll House) #357 - Meggendorfer Das Puppenhaus #195 - Detmold Arabian Nights #526 - Dr. Seuss original art #326 - Dorothy Lathrop drawing - Kou Hsiung (Pekingese) #265 - The Magic Cube - 19th century (ca. 1840) educational game Helen & Marc Younger Pg 3 [email protected] THE ITEMS IN THIS CATALOGUE WILL NOT BE ON RARE TUCK RAG “BLACK” ABC 5. ABC. (BLACK) MY HONEY OUR WEB SITE FOR A FEW WEEKS. -

THE LAND BEYOND the MAGIC MIRROR by E

GREYHAWK CASTLE DUNGEON MODULE EX2 THE LAND BEYOND THE MAGIC MIRROR by E. Gary Gygax AN ADVENTURE IN A WONDROUS PLACE FOR CHARACTER LEVELS 9-12 No matter the skill and experience of your party, they will find themselves dazed and challenged when they pass into The Land Beyond the Magic Mirror! Distributed to the book trade in the United States by Random House, Inc. and in Canada by Random House of Canada Ltd. Distributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. Distributed in the United Kingdom by TSR Hobbies (UK) Ltd. AD&D and WORLD OF GREYHAWK are registered trademarks owned by TSR Hobbies, Inc. ©1983 TSR Hobbies, Inc. All Rights Reserved. TSR Hobbies, Inc. TSR Hobbies (UK) Ltd. POB 756 The Mill, Rathmore Road Lake Geneva, Cambridge CB14AD United Kingdom Printed in U.S.A. WI 53147 ISBN O 88038-025-X 9073 TABLE OF CONTENTS This module is the companion to Dungeonland and was originally part of the Greyhawk Castle dungeon complex. lt is designed so that it can be added to Dungeonland, used alone, or made part of virtually any campaign. It has an “EX” DUNGEON MASTERS PREFACE ...................... 2 designation to indicate that it is an extension of a regular THE LAND BEYOND THE MAGIC MIRROR ............. 4 dungeon level—in the case of this module, a far-removed .................... extension where all adventuring takes place on another plane The Magic Mirror House First Floor 4 of existence that is quite unusual, even for a typical AD&D™ The Cellar ......................................... 6 Second Floor ...................................... 7 universe. This particular scenario has been a consistent ......................................... -

ALICE's ADVENTURES in WONDERLAND Lewis Carroll

The Jefferson Performing Arts Society Presents 1118 Clearview Parkway Metairie, LA 70001 504-885-2000 www.jpas.org 1 | P a g e Table of Contents Teacher’s Notes………………………..…………..…………..……..3 Standards and Benchmarks…………………..……………….…..5 Background………………………………………..…….………………6 Alice’s Adventures, Comparing and Contrasting ………… 12 Art, Math and Set Design: Alice in Minecraft Land...................................................33 The Science of Color Meets the White Rabbit and the March Hare...................74 Additional Resources…………………………………..…..….….106 2 | P a g e Teacher’s Notes Music and Lyrics by Sammy Fain and Bob Hilliard, Oliver Wallace and Cy Coban, Allie Wrubel and Ray Gilbert, Mack David, Al Hoffman and Jerry Livingston Music Adapted and Arranged and Additional Music and Lyrics by Bryan Louiselle Book Adapted and Additional Lyrics by David Simpatico Based on the 1951 Disney film, Alice in Wonderland, and the Lewis Carroll novels, "The Adventures of Alice in Wonderland" and "Through the Looking Glass," Lewis Carroll's famous heroine comes to life in this delightful adaptation of the classic Disney film. Lewis Carroll was the nom de plume of Charles L. Dodgson. Born on January 27, 1832 in Daresbury, Cheshire, England, Charles Dodgson wrote and created games as a child. At age 20 he received a studentship at Christ Church and was appointed a lecturer in mathematics. Dodgson was shy but enjoyed creating stories for children. Within the academic discipline of mathematics, Dodgson worked primarily in the fields of geometry, linear and matrix algebra, mathematical logic, and recreational mathematics, producing nearly a dozen books under his real name. Dodgson also developed new ideas in linear algebra (e.g., the first printed proof of the Kronecker-Capelli theorem,) probability, and the study of elections (e.g., Dodgson's method); some of this work was not published until well after his death. -

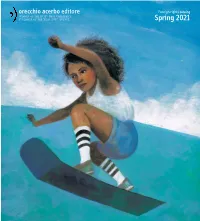

Orecchio Acerbo Rights List Spring 2021

orecchio acerbo editore Foreign rights catalog Winner of the BoP · Best Children’s PuBlisher of the Year 2017, euroPe Spring 2021 picture books daybrEak NEW by Daniel Fehr illustrations Elena Rotondo for children 4 years and older pp. 28 | cm. 23 x 21 ISBN 9788832070651 | July 2021 today NEW by Daniel Fehr big quEstioNs | grEat advENturEs illustrations Simone Rea WaitiNg for Walt for children 4 years and older by Daniel Fehr The story is about a young boy and his father. pp. 64 | cm. 17 x 24 illustrations Maja Celjia In the middle of the night they leave their house. ISBN 9788832070590 | April 2021 for children 5 years and older For the boy it is the first time that he leaves home pp. 32 | cm. 24 x 32 | May 2020 at this time of the night when normally uNdEr thE gazE of timE | rEcouNtiNg thE prEsENt he is asleep. As they walk through the forest storiEs of thE visioNary aNd thE absurd laughtEr aNd smilEs the flashlight of the boy “turns on” part A father who is leaving. Two brothers. A long wait. of the vegetation and at the same time the rest But together it is easier, together it is easy disappear. He turns off the flashlight and “turns on” to be strong. The older brother reads books Two kids are waiting for Walt. But who is Walt? all his senses: he experiences the darkness, to the younger one who can’t read yet but can And, if Walt was there with them, what would the sounds of the forest, the sound of his father, at least choose the book; then they go together they all do together? They would have a lot the roughness of the ground, the smells… on a secret mission: is every mission of spies of fun, because when he is there he always He dares not ask for the space and time secret? Then one goes to play football, the other has crazy ideas. -

Examining the Relationship Between Children's

A Spoonful of Silly: Examining the Relationship Between Children’s Nonsense Verse and Critical Literacy by Bonnie Tulloch B.A., (Hons), Simon Fraser University, 2013 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Children’s Literature) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2015 © Bonnie Tulloch, 2015 Abstract This thesis interrogates the common assumption that nonsense literature makes “no sense.” Building off research in the fields of English and Education that suggests the intellectual value of literary nonsense, this study explores the nonsense verse of several North American children’s poets to determine if and how their play with language disrupts the colonizing agenda of children’s literature. Adopting the critical lenses of Translation Theory and Postcolonial Theory in its discussion of Dr. Seuss’s On Beyond Zebra! (1955) and I Can Read with My Eyes Shut! (1978), along with selected poems from Shel Silverstein’s Where the Sidewalk Ends (1974), A Light in the Attic (1981), Runny Babbit (2005), Dennis Lee’s Alligator Pie (1974), Nicholas Knock and Other People (1974), and JonArno Lawson’s Black Stars in a White Night Sky (2006) and Down in the Bottom of the Bottom of the Box (2012), this thesis examines how the foreignizing effect of nonsense verse exposes the hidden adult presence within children’s literature, reminding children that childhood is essentially an adult concept—a subjective interpretation (i.e., translation) of their lived experiences. Analyzing the way these poets’ nonsense verse deviates from cultural norms and exposes the hidden adult presence within children’s literature, this research considers the way their poetry assumes a knowledgeable implied reader, one who is capable of critically engaging with the text. -

Alice Through the Looking-Glass Is Presented by Special Arrangement with the Estate of James Crerar Reaney

This production was originally produced at the Stratford Festival in association with Canada’s National Arts Centre in 2014. nov dec 26 19 2015 THEATRE FOR YOUNG AUDIENCES GENEROUSLY SUPPORTED BY STUDY GUIDE Adapted from the Stratford Festival 2014 Study Guide by Luisa Appolloni This production was originally produced at the Stratford Festival in association with Canada's National Arts Centre in 2014. Alice Through the Looking-Glass is presented by special arrangement with the Estate of James Crerar Reaney. 1 THEATRE ETIQUETTE “The theater is so endlessly fascinating because it's so accidental. It's so much like life.” – Arthur Miller Arrive Early: Latecomers may not be admitted to a performance. Please ensure you arrive with enough time to find your seat before the performance starts. Cell Phones and Other Electronic Devices: Please TURN OFF your cell phones/iPods/gaming systems/cameras. We have seen an increase in texting, surfing, and gaming during performances, which is very distracting for the performers and other audience members. The use of cameras and recording devices is strictly prohibited. Talking During the Performance: You can be heard (even when whispering!) by the actors onstage and the audience around you. Disruptive patrons will be removed from the theatre. Please wait to share your thoughts and opinions with others until after the performance. Food/Drinks: Food and hot drinks are not allowed in the theatre. Where there is an intermission, concessions may be open for purchase of snacks and drinks. There is complimentary water in the lobby. Dress: There is no dress code at the Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre, but we respectfully reQuest that patrons refrain from wearing hats in the theatre. -

ARTICLE: Jan Susina: Playing Around in Lewis Carroll's Alice Books

Playing Around in Lewis Carroll’s Alice Books • Jan Susina Mathematician Charles Dodgson’s love of play and his need for rules came together in his use of popular games as part of the structure of the two famous children’s books, Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, he wrote under the pseudonym Lewis Carroll. The author of this article looks at the interplay between the playing of such games as croquet and cards and the characters and events of the novels and argues that, when reading Carroll (who took a playful approach even in his academic texts), it is helpful to understand games and game play. Charles Dodgson, more widely known by his pseudonym Lewis Carroll, is perhaps one of the more playful authors of children’s literature. In his career, as a children’s author and as an academic logician and mathematician, and in his personal life, Carroll was obsessed with games and with various forms of play. While some readers are surprised by the seemingly split personality of Charles Dodgson, the serious mathematician, and Lewis Carroll, the imaginative author of children’s books, it was his love of play and games and his need to establish rules and guidelines that effectively govern play that unite these two seemingly disparate facets of Carroll’s personality. Carroll’s two best-known children’s books—Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking- Glass and What Alice Found There (1871)—use popular games as part of their structure. In Victoria through the Looking-Glass, Florence Becker Lennon has gone so far as to suggest about Carroll that “his life was a game, even his logic, his mathematics, and his singular ordering of his household and other affairs. -

1.Hum-Roald Dahl's Nonsense Poetry-Snigdha Nagar

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) ISSN(P): 2347-4564; ISSN(E): 2321-8878 Vol. 4, Issue 4, Apr 2016, 1-8 © Impact Journals ROALD DAHL’ S NONSENSE POETRY: A METHOD IN MADNESS SNIGDHA NAGAR Research Scholar, EFL University, Tarnaka, Hyderabad, India ABSTRACT Following on the footsteps of writers like Louis Carroll, Edward Lear, and Dr. Seuss, Roald Dahl’s nonsensical verses create a realm of semiotic confusion which negates formal diction and meaning. This temporary reshuffling of reality actually affirms that which it negates. In other words, as long as it is transitory the ‘nonsense’ serves to establish more firmly the authority of the ‘sense.’ My paper attempts to locate Roald Dahl’s verse in the field of literary nonsense in as much as it avows that which it appears to parody. Set at the brink of modernism these poems are a playful inditement of Victorian conventionality. The three collections of verses Rhyme Stew, Dirty Beasts, and Revolving Rhyme subvert social paradigms through their treatment of censorship and female sexuality. Meant primarily for children, these verses raise a series of uncomfortable questions by alienating the readers with what was once familiar territory. KEYWORDS : Roald Dahl’s Poetry, Subversion, Alienation, Meaning, Nonsense INTRODUCTION The epistemological uncertainty that manifested itself during the Victorian mechanization reached its zenith after the two world wars. “Even signs must burn.” says Jean Baudrillard in For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign (1981).The metaphor of chaos was literalized in works of fantasy and humor in all genres. -

Humour in Nonsense Literature

http://dx.doi.org/10.7592/EJHR2017.5.3.holobut European Journal of Humour Research 5 (3) 1–3 www.europeanjournalofhumour.org Editorial: Humour in nonsense literature Agata Hołobut Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland [email protected] Władysław Chłopicki Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland [email protected] The present special issue is quite unique. It grew out of a one-off scholarly seminar entitled BLÖÖF: Nonsense in Translation and Beyond, which attracted international scholars to the Institute of English Studies of Kraków’s Jagiellonian University on 18 May 2016 – a venue which had earlier yielded the series of studies entitled In Search of (Non)Sense (Chrzanowska- Kluczewska & Szpila 2009). The discussion at the seminar brought everyone to the, perhaps inevitable, conclusion that nonsense is bound to be humorous, and thus nonsense is definitely within the scope of humour studies. “Nonsense expressions easily become humorous ones, as humans often obtain pleasure from linguistic play and are ready to look for alternative paths to produce meaning. Nonsense has been experienced as a form of freedom, especially as a means to free thinking from the conventional bindings of logic and language” (Viana 2014). The interest in literary nonsense is quite long dating back to such grand figures as Dante, Rabelais, Erasmus of Rotterdam, and especially notably to the Anglosphere with its grand figures of Jonathan Swift, Lawrence Sterne, Edward Lear, Lewis Carroll, James Joyce, and Samuel Beckett. At least since the time of Lewis Carroll and the antics of Alice in Wonderland nonsense humour rose to the status of a ‘typically English’ phenomenon, and the subject of creative nonsense or sense in nonsense has been quite prominent in English-language literary studies, whether of verse or prose. -

Annihilating Nihilistic Nonsense Tim Burton Guts Lewis Carroll’S Jabberwocky

Annihilating Nihilistic Nonsense Tim Burton Guts Lewis Carroll’s Jabberwocky Alice in Wonderland seems to beg for a morbid interpretation. Whether it's Marilyn Manson's "Eat Me, Drink Me," the video game "American McGee's Alice," or Svankmajer's "Alice" and "Jabberwocky," artists love bringing out the darker elements of Alice’s adventures as she wanders among creepy creatures. The 2010 Tim Burton film is the latest twisted adaptation, featuring an older Alice that slays the Jabberwocky. However, unlike the other adaptations, Burton’s adaptation draws most of its grim outlook by gutting Alice in Wonderland of its fundamental core - its nonsense. Alice in Wonderland uses nonsense to liberate, offering frightening amounts of freedom through its playful use of nonsense. However, Burton turns this whimsy into menacing machinations - he pretends to use nonsense for its original liberating purpose but actually uses it for adult plots and preset paths. Burton takes the destructive power of Alice’s insistence for order and amplifies it dramatically, completely removing its original subversive release from societal constraints. Under the façade of paying tribute to Carroll’s whimsical nonsense verse, Burton directly removes nonsense’s anarchic freedom and replaces it with a destructive commitment to sense. This brutal change to both plot and structure turns Alice into a mindless juggernaut, slaying not only the Jabberwock, but also the realm of nonsense, non-linear narrative and real world empires. At first, nonsense in Lewis Carroll’s books seems to just a light-hearted play with language. Even before we come into Wonderland, the idea of nonsense as just a simple child’s diversion is given by the epigraph. -

Finding Sense Behind Nonsense in Select Poems of Sukumar Ray

Journal of the Department of English Vidyasagar University Vol. 12, 2014-2015 Finding Sense Behind Nonsense in Select Poems of Sukumar Ray Rima Chakraborty Nonsense literature is generally categorized as part of the macrocosm of children’s literature. And there is no denying that as children we have all read such literary pieces with much amusement and delight. In 1900 G.K. Chesterton wrote that, if he were to be asked for the best proof of ‘adventurous growth’ in the nineteenth century, he would reply, “with all respect for its portentous science and philosophy, that it was to be found in the literature of nonsense” and that “this was the literature of the future” (Chesterton 43). Now, “Nonsense” as a literary genre is difficult to define in absolute terms. It is interpretation gone wild, but also lucid, as clearly appears in the works of the early practitioners of the form in the mid 19th century, namely Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll. It is true that the “modern nonsense” originated in the mid- 19th century, but it is equally true that the roots of the tradition can be traced back to some of its early practitioners and precursors- such as the anonymous nonsense of nursery rhymes, the ‘water poet’ John Taylor and the Bedlamite and mad talk of Shakespeare. Again, if the genre of literary nonsense is analyzed with reference to its contemporary socio-political scenario, it becomes clear that nonsense is actually a medium which allows the literary artist to point out various shortcomings of the society at large. So, as its name suggests, “non-sense” always exists in relation to, and as a comment on, “sense.” T. -

The Female Rebel in Pan's Labyrinth, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass

GOTHIC AGENTS OF REVOLT: THE FEMALE REBEL IN PAN'S LABYRINTH, ALICE'S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND AND THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS Michail-Chrysovalantis Markodimitrakis A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2016 Committee: Piya-Pal Lapinski, Advisor Kimberly Coates © 2016 Michail-Chrysovalantis Markodimitrakis All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Piya Pal-Lapinski, Advisor The Gothic has become a mode of transforming reality according to the writers’ and the audiences’ imagination through the reproduction of hellish landscapes and nightmarish characters and occurrences. It has also been used though to address concerns and criticize authoritarian and power relations between citizens and the State. Lewis Carroll’sAlice’s Adventures in Wonderland and its sequel Through the Looking Glass are stories written during the second part of the 19th century and use distinct Gothic elements to comment on the political situation in England as well as the power of language from a child’s perspective. Guillermo Del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth on the other hand uses Gothic horror and escapism to demonstrate the monstrosities of fascism and underline the importance of revolt and resistance against State oppression. This thesis will be primarily concerned with Alice and Ophelia as Gothic protagonists that become agents of revolt against their respective states of oppression through the lens of Giorgio Agamben and Hannah Arendt. I will examine how language and escapism are used as tools by the literary creators to depict resistance against the Law and societal pressure; I also aim to demonstratehow the young protagonists themselves refuse to comply with the authoritarian methods used against them byadult the representatives of Power.