India/Postcolonial Focus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fabric Story: India- Fabrics and Embroideries

Humber Fashion Institute Fabric Story: India- Fabrics and Embroideries FMPC 505 01 Nilofer Timol 10/18/2013 Contents Humber Fashion Institute ....................................................................................................................................................... 0 Fabric Story: India- Fabrics and Embroideries ........................................................................................................................ 0 FMPC 505 01 ........................................................................................................................................................................... 0 Table of Figures ....................................................................................................................................................................... 2 India: Fabrics and Embroideries .............................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................ 3 The Fabric Story ...................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Fashion Theme ............................................................................................................................................................... -

"Animals in Saki's Short Stories Within the Context of Imperialism: a Non

Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of English Language and Literature ANIMALS IN SAKI’S SHORT STORIES WITHIN THE CONTEXT OF IMPERIALISM: A NON-ANTHROPOCENTRIC APPROACH Adem Balcı Master’s Thesis Ankara, 2014 ANIMALS IN SAKI’S SHORT STORIES WITHIN THE CONTEXT OF IMPERIALISM: A NON-ANTHROPOCENTRIC APPROACH Adem Balcı Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of English Language and Literature Master’s Thesis Ankara, 2014 iii To my family iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to my supervisor Assist. Prof. Dr. Sinan AKILLI for his encouragement, friendship, and academic guidance. Without his never-ending support, encouragement, constructive criticism, unwavering belief in me, unending patience, genuine kindness, suggestions, meticulous feedbacks and comments, this thesis would not be what it is now. I would also like to express my deepest gratitude to Prof. Dr. Burçin EROL, the Head of the Department of English Language and Literature, for her endless support, warm welcome, motivation and encouragement whenever I needed. I wish to express my sincere gratitude to the distinguished members of the Examining Committee who contributed to this thesis through their constructive comments and meticulous feedback. Firstly, I would like to thank Prof. Dr. Deniz BOZER for her suggestions, invaluable comments, and academic guidance in each step of this thesis. I would also like to thank Prof. Dr. Serpil OPPERMANN wholeheartedly for introducing me to the posthumanities and animal studies, for helping me to write my thesis proposal and finally for her contribution to the development of this thesis with her invaluable comments, her books, and feedbacks. -

GI Journal No. 75 1 November 26, 2015

GI Journal No. 75 1 November 26, 2015 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS JOURNAL NO.75 NOVEMBER 26, 2015 / AGRAHAYANA 05, SAKA 1936 GI Journal No. 75 2 November 26, 2015 INDEX S. No. Particulars Page No. 1 Official Notices 4 2 New G.I Application Details 5 3 Public Notice 6 4 GI Applications Bagh Prints of Madhya Pradesh (Logo )- GI Application No.505 7 Sankheda Furniture (Logo) - GI Application No.507 19 Kutch Embroidery (Logo) - GI Application No.509 26 Karnataka Bronzeware (Logo) - GI Application No.510 35 Ganjifa Cards of Mysore (Logo) - GI Application No.511 43 Navalgund Durries (Logo) - GI Application No.512 49 Thanjavur Art Plate (Logo) - GI Application No.513 57 Swamimalai Bronze Icons (Logo) - GI Application No.514 66 Temple Jewellery of Nagercoil (Logo) - GI Application No.515 75 5 GI Authorised User Applications Patan Patola – GI Application No. 232 80 6 General Information 81 7 Registration Process 83 GI Journal No. 75 3 November 26, 2015 OFFICIAL NOTICES Sub: Notice is given under Rule 41(1) of Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration & Protection) Rules, 2002. 1. As per the requirement of Rule 41(1) it is informed that the issue of Journal 75 of the Geographical Indications Journal dated 26th November 2015 / Agrahayana 05th, Saka 1936 has been made available to the public from 26th November 2015. GI Journal No. 75 4 November 26, 2015 NEW G.I APPLICATION DETAILS App.No. Geographical Indications Class Goods 530 Tulaipanji Rice 31 Agricultural 531 Gobindobhog Rice 31 Agricultural 532 Mysore Silk 24, 25 and 26 Handicraft 533 Banglar Rasogolla 30 Food Stuffs 534 Lamphun Brocade Thai Silk 24 Textiles GI Journal No. -

Saki / H.H. Munro 1870-1916 Bios

Saki / H.H. Munro 1870-1916 Bios http://www.litgothic.com/Authors/saki.html Up to now, little has been known about Hector Hugh Munro except that he used the pen name “Saki”; that he wrote a number of witty short stories, two novels, several plays, and a history of Russia; and that he was killed in World War I. His friend Rothay Reynolds published “A Memoir of H. H. Munro” in Saki’s The Toys of Peace (1919), and Munro’s sister Ethel furnished a brief “Biography of Saki” for a posthumous collection of his work entitled The Square Egg and Other Sketches (1924). A. J. Langguth’s Saki is the first full-length biography of the man who, during his brief writing career, published a succession of bright, satirical, and sometimes perfectly crafted short stories that have entertained and amused readers in many countries for well over a half-century. Hector Munro was the third child of Charles Augustus Munro, a British police officer in Burma, and his wife Mary Frances. The children were all born in Burma. Pregnant with her fourth child, Mrs. Munro was brought with the children to live with her husband’s family in England until the child arrived. Frightened by the charge of a runaway cow on a country lane, Mrs. Munro died after a miscarriage. Since the widowed father had to return to Burma, the children — Charles, Ethel, and Hector — were left with their Munro grandmother and her two dominating and mutually antagonistic spinster daughters, Charlotte (“Aunt Tom”) and Augusta. This situation would years later provide incidents, characters, and themes for a number of Hector Munro’s short stories as well as this epitaph for Augusta by Ethel: “A woman of ungovernable temper, of fierce likes and dislikes, imperious, a moral coward, possessing no brains worth speaking of, and a primitive disposition. -

Not for Sale, Program That Works, and We’D but It Might Be Moving Like to Bring It to More Schools Soon, According to Owner Across the County.” Chris Redd

Covering all of Baldwin County, AL every Friday. The Baldwin Times State track meet titles PAGE 15 MAY 12, 2017 | GulfCoastNewsToday.com | 75¢ County, Fairhope at odds yet Baldwin again on county road repairs schools By CLIFF MCCOLLUM message boards to County projects. moving [email protected] Road 32 near the intersec- The list includes the fol- tion with Highway 181 lowing: Tensions have once displaying a message to • CR48 just West of Bo- again flared between the motorists and the city hemian Hall Rd forward Baldwin County Com- itself: “Delays caused by According to notes mission and the city of Fairhope Utility. Call 928- from the Baldwin County Academic plan has 4 Fairhope’s utilities depart- 2136.” Highway Department: major components ment following continued The county said several “This site is currently discussions and problems roads, including County open to the public. We By CLIFF MCCOLLUM involving needed upgrades Road 32, have been held have received a quote from [email protected] to county roads on the up for far too long. County Fairhope Water & Sewer PHOTO BY CLIFF MCCOLLUM city’s borders. officials said the holdup to relocate this conflict. During a recent special called County officials moved message boards along Late Tuesday afternoon, Baldwin County Board of Edu- County Road 32 that urged residents upset has been utility line re- The City of Fairhope has by construction delays to contact the City of the county moved the locations near or around the utility agreement and cation work session, Baldwin Fairhope’s utilities department. highway department’s the various uncompleted SEE ROADS, PAGE 25 County Schools Academic Dean Joyce Woodburn laid out an academic plan for the board members comprised of four major components. -

In Commemoration of Hector Munro, 'Saki' Transcript

The grinning shadow that sat at the feast: In commemoration of Hector Munro, 'Saki' Transcript Date: Tuesday, 14 November 2006 - 12:00AM The Grinning Shadow that sat at the Feast: an appreciation of the life and work of Hector Munro 'Saki' Professor Tim Connell Hector Munro was a man of many parts, and although he died relatively young, he lived through a time of considerable change, had a number of quite separate careers and a very broad range of interests. He was also a competent linguist who spoke Russian, German and French. Today is the 90th anniversary of his death in action on the Somme, and I would like to review his importance not only as a writer but also as a figure in his own time. Early years to c.1902 Like so many Victorians, he was born into a family with a long record of colonial service, and it is quite confusing to see how many Hector Munros there are with a military or colonial background. Our Hector’s most famous ancestor is commemorated in a well-known piece at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Tippoo's Tiger shows a man being eaten by a mechanical tiger and the machine emits both roaring and groaning sounds. 1 Hector's grandfather was an Admiral, and his father was in the Burma Police. The family was hit by tragedy when Hector's mother was killed in a bizarre accident involving a runaway cow. It is curious that strange events involving animals should form such a common feature of Hector's writing 2 but this may also derive from his upbringing in the Devonshire countryside and a home that was dominated by the two strangest creatures of all - Aunt Augusta and Aunt Tom. -

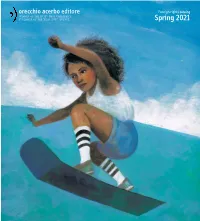

Orecchio Acerbo Rights List Spring 2021

orecchio acerbo editore Foreign rights catalog Winner of the BoP · Best Children’s PuBlisher of the Year 2017, euroPe Spring 2021 picture books daybrEak NEW by Daniel Fehr illustrations Elena Rotondo for children 4 years and older pp. 28 | cm. 23 x 21 ISBN 9788832070651 | July 2021 today NEW by Daniel Fehr big quEstioNs | grEat advENturEs illustrations Simone Rea WaitiNg for Walt for children 4 years and older by Daniel Fehr The story is about a young boy and his father. pp. 64 | cm. 17 x 24 illustrations Maja Celjia In the middle of the night they leave their house. ISBN 9788832070590 | April 2021 for children 5 years and older For the boy it is the first time that he leaves home pp. 32 | cm. 24 x 32 | May 2020 at this time of the night when normally uNdEr thE gazE of timE | rEcouNtiNg thE prEsENt he is asleep. As they walk through the forest storiEs of thE visioNary aNd thE absurd laughtEr aNd smilEs the flashlight of the boy “turns on” part A father who is leaving. Two brothers. A long wait. of the vegetation and at the same time the rest But together it is easier, together it is easy disappear. He turns off the flashlight and “turns on” to be strong. The older brother reads books Two kids are waiting for Walt. But who is Walt? all his senses: he experiences the darkness, to the younger one who can’t read yet but can And, if Walt was there with them, what would the sounds of the forest, the sound of his father, at least choose the book; then they go together they all do together? They would have a lot the roughness of the ground, the smells… on a secret mission: is every mission of spies of fun, because when he is there he always He dares not ask for the space and time secret? Then one goes to play football, the other has crazy ideas. -

Beasts and Super-Beasts: by Saki Online

j1Zfo [E-BOOK] Beasts and Super-Beasts: by Saki Online [j1Zfo.ebook] Beasts and Super-Beasts: by Saki Pdf Free Saki Saki *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook 2017-01-07 2017-01-07File Name: B01NBSEDIW | File size: 52.Mb Saki Saki : Beasts and Super-Beasts: by Saki before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Beasts and Super-Beasts: by Saki: 5 of 5 people found the following review helpful. Saki at his bestBy Robert GuttmanBeasts and Super-Beasts comprises thirty-seven short stories from the pen of the incomparable Saki, which was the pen-name for H. H. Munro. Saki's ironic and witty stories chronicled the British upper class during the Edwardian period, the era that represented the zenith of British power and complacency just before the cataclysm of World War I. The quality of his wit and satiric humor are of the very highest order, comparable to very best of Oscar Wilde and Ambrose Bierce. As with Bierce, a touch of cruelty was often present in Saki's humor. In addition, Saki also shared with Bierce a taste for the supernatural, a quality which comes across in many of the stories in this particular collection.Reading Saki is an absolute must for any aspiring writer, and an absolute pleasure for readers everywhere.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Gotta love Saki!By Kevin BeachyIf you like Mark Twain's particular strain of sarcastic humor, you gotta try Saki. -

We Are Manufacturing and Exporting Ethnic Wear for Men, Women & Kids

We are manufacturing and exporting ethnic wear for men, women & kids and includes embroidered bridal lehenga, salwar suit & fashion accessories. Our range is popular across the US market for quality, variety, embroidery and fabric used. - Company Brief - Started in 1990, we Dot Exports cater to international buyers with our range of ethnic bridal wear, ladies saree, ladies suits, men's wear, kid's wear, indian fashion jewelry & accessories. Our extensive range of ethnic garments & accessories are best suitable for wedding trousseau. From lehenga-choli, fancy sari, salwar kameez & more for women to sherwani, jodhpuri suits & kurta for men, we have it all. Our range also encompasses ethnic dresses for kids. To match the garments styling, we offer variety of embroidered safas, stoles, dupattas, juti or mojaris, etc. Our efforts are to deliver uniqueness in each item, so our workshops nurture some of the best designers & karigars, who have the expertise to create awesome fabric wonders. Our workers & supervisors have good understanding of intricacies and fineness of Indian embroidery & embellishment that highlights our range in the global market. Operating since 1990, we Dot Exports are a recognized manufacturer & exporter of Indian ethnic garment, fashion accessories & traditional jewelery. Our vast range includes bridal wears, sarees, ladies suits, ethnic wear for men, Indian outfits for kids, fashion jewelery and accessories. As a noted exporter to US markets, we combine the dexterity of our designers with the requirements of the fashion conscious global market and make our product-line perfect to suit all seasons and occasions. Adding glamor to the wedding wardrobes, all our products are known for quality in terms of fabric, workmanship & tailoring expertise. -

Wedding Sherwani, Indo Western Sherwani, Kurta Pajama and Many More

+91-8048600930 Kinny Garments Private Limited https://www.kinnygarments.in/ We are one of the leading manufacturers, suppliers and exporters of optimum quality Mens Wedding Dresses. Owing to their attractive design and trendy appearance, these men’s wedding dresses are highly demanded in the market. About Us We, Kinny Garments Private Limited set up in the year 1988, are among the prominent manufacturers, suppliers and exporters of an extensive range of optimum quality Mens Wedding Dresses. The range of products offered by us are given as Wedding Sherwani, Indo Western Sherwani, Kurta Pajama and many more. The fabric yarns, which are best in the market, are used for the purpose of precisely designing the offered men’s wedding dresses. For the purpose of designing the offered wedding dressing in adherence to the prevailing fashion, the skilled designers and advanced weaving machines are used. These dresses are known in the market for their appealing design, resistance to fading & shrinkage, excellent sheen, smooth finish, vibrant color combination and durability. Owing to our large production capacity, we have been able to meet the bulk demands within the stipulated time frame. These wedding dresses can be customized as per the specifications provided by the customers. It is owing to our state-of-the-art infrastructure that we have been able to cater to the precise needs of our valuable customers in the most efficient manner. We, being a quality certified organization, assure the premium quality of the offered dresses is maintained at all times. For delivering the offered products at the customers’ end, we have set up a huge distribution network that is well connected with different modes of transport. -

THE WESTFIELD LEADER the Leading and Most Widely Circulated Weekly Newspaper in Union County Pfieventh YEAR—No

•"•*. THE WESTFIELD LEADER The Leading And Most Widely Circulated Weekly Newspaper In Union County PfiEVENTH YEAR—No. 32 li.llt.eieU M OtoUUllli 1.1U9* . P> Offl TVtflM WESTFIELD. NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, APRIL 18, 1957 36 Pagei—10 Cent* Westfield Club Primary Vote In Westfield [an Eastertide REPUBLICAN Displays Flowers IW 2W 3W 4W Tot.l Light Vote Tallied Here GOVERNOR Forbes 813 f>47 458 381 2,299 At Public Show Dumont 317 216 187 137 857 lurch Services ASSEMBLY In Quiet Primary Election Griffin . 680 511 367 304 1,862 First Event Rand 190 133 148 109 580 Paris To Be Scene Set At Local Murray , 369 310 222 156 1,057 No Opposition liial Good Of Sunrise Service Thomas 819 037 464 381 2,301 Irene Griffin No Contests For Homes May 9 Vanderbilt 813 627 436 367 2,243 In Mountainside Crane „ . 825 652 459 364 2,300 lay Devotion An Easter Sunday, sunrise serv- Mrs. Torg Tonnessen, president Stamler . 427 319 217 197 1,160 Wins County GOP MOUNTAINSIDE — With Either Party ice will be held at Mindowaskin of the Rake and Hoe Garden Club Velbinger 120 80 109 69 378 •oting described as "extremely Park this week at 0 a.m. under of Westfield, has announced the ight," Mayor Joseph A. C. Komich first Baptist the sponsorship of the youth com- FREEHOLDERS club will hold its first public open Bailey 1,022 805 569 454 2,850 Nod For Assembly nd Councilmen Ronald L. Farrell On Local Scene mittee of the Westfield Council of home flower show May 9. -

Honour List 2018 © International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY), 2018

HONOUR LIST 2018 © International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY), 2018 IBBY Secretariat Nonnenweg 12, Postfach CH-4009 Basel, Switzerland Tel. [int. +4161] 272 29 17 Fax [int. +4161] 272 27 57 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.ibby.org Book selection and documentation: IBBY National Sections Editors: Susan Dewhirst, Liz Page and Luzmaria Stauffenegger Design and Cover: Vischer Vettiger Hartmann, Basel Lithography: VVH, Basel Printing: China Children’s Press and Publication Group (CCPPG) Cover illustration: Motifs from nominated books (Nos. 16, 36, 54, 57, 73, 77, 81, 86, 102, www.ijb.de 104, 108, 109, 125 ) We wish to kindly thank the International Youth Library, Munich for their help with the Bibliographic data and subject headings, and the China Children’s Press and Publication Group for their generous sponsoring of the printing of this catalogue. IBBY Honour List 2018 IBBY Honour List 2018 The IBBY Honour List is a biennial selection of This activity is one of the most effective ways of We use standard British English for the spelling outstanding, recently published children’s books, furthering IBBY’s objective of encouraging inter- foreign names of people and places. Furthermore, honouring writers, illustrators and translators national understanding and cooperation through we have respected the way in which the nomi- from IBBY member countries. children’s literature. nees themselves spell their names in Latin letters. As a general rule, we have written published The 2018 Honour List comprises 191 nomina- An IBBY Honour List has been published every book titles in italics and, whenever possible, tions in 50 different languages from 61 countries.