Alice's Adventures in Adaptation: the Evolution of Power In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Maryallenfinal Thesis.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH SIX IMPOSSIBLE THINGS BEFORE BREAKFAST: THE LIFE AND MIND OF LEWIS CARROLL IN THE AGE OF ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND MARY ALLEN SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in English with honors in English Reviewed and approved* by the following: Kate Rosenberg Assistant Teaching Professor of English Thesis Supervisor Christopher Reed Distinguished Professor of English, Visual Culture, and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Honors Adviser * Electronic approvals are on file. i ABSTRACT This thesis analyzes and offers connections between esteemed children’s literature author Lewis Carroll and the quality of mental state in which he was perceived by the public. Due to the imaginative nature of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, it has been commonplace among scholars, students, readers, and most individuals familiar with the novel to wonder about the motive behind the unique perspective, or if the motive was ever intentional. This thesis explores the intentionality, or lack thereof, of the motives behind the novel along with elements of a close reading of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. It additionally explores the origins of the concept of childhood along with the qualifications in relation to time period, culture, location, and age. It identifies common stereotypes and presumptions within the subject of mental illness. It aims to achieve a connection between the contents of Carroll’s novel with -

THE LAND BEYOND the MAGIC MIRROR by E

GREYHAWK CASTLE DUNGEON MODULE EX2 THE LAND BEYOND THE MAGIC MIRROR by E. Gary Gygax AN ADVENTURE IN A WONDROUS PLACE FOR CHARACTER LEVELS 9-12 No matter the skill and experience of your party, they will find themselves dazed and challenged when they pass into The Land Beyond the Magic Mirror! Distributed to the book trade in the United States by Random House, Inc. and in Canada by Random House of Canada Ltd. Distributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. Distributed in the United Kingdom by TSR Hobbies (UK) Ltd. AD&D and WORLD OF GREYHAWK are registered trademarks owned by TSR Hobbies, Inc. ©1983 TSR Hobbies, Inc. All Rights Reserved. TSR Hobbies, Inc. TSR Hobbies (UK) Ltd. POB 756 The Mill, Rathmore Road Lake Geneva, Cambridge CB14AD United Kingdom Printed in U.S.A. WI 53147 ISBN O 88038-025-X 9073 TABLE OF CONTENTS This module is the companion to Dungeonland and was originally part of the Greyhawk Castle dungeon complex. lt is designed so that it can be added to Dungeonland, used alone, or made part of virtually any campaign. It has an “EX” DUNGEON MASTERS PREFACE ...................... 2 designation to indicate that it is an extension of a regular THE LAND BEYOND THE MAGIC MIRROR ............. 4 dungeon level—in the case of this module, a far-removed .................... extension where all adventuring takes place on another plane The Magic Mirror House First Floor 4 of existence that is quite unusual, even for a typical AD&D™ The Cellar ......................................... 6 Second Floor ...................................... 7 universe. This particular scenario has been a consistent ......................................... -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

Readercon 14

readercon 14 program guide The conference on imaginative literature, fourteenth edition readercon 14 The Boston Marriott Burlington Burlington, Massachusetts 12th-14th July 2002 Guests of Honor: Octavia E. Butler Gwyneth Jones Memorial GoH: John Brunner program guide Practical Information......................................................................................... 1 Readercon 14 Committee................................................................................... 2 Hotel Map.......................................................................................................... 4 Bookshop Dealers...............................................................................................5 Readercon 14 Guests..........................................................................................6 Readercon 14: The Program.............................................................................. 7 Friday..................................................................................................... 8 Saturday................................................................................................14 Sunday................................................................................................. 21 Readercon 15 Advertisement.......................................................................... 26 About the Program Participants......................................................................27 Program Grids...........................................Back Cover and Inside Back Cover Cover -

Not for Sale, Program That Works, and We’D but It Might Be Moving Like to Bring It to More Schools Soon, According to Owner Across the County.” Chris Redd

Covering all of Baldwin County, AL every Friday. The Baldwin Times State track meet titles PAGE 15 MAY 12, 2017 | GulfCoastNewsToday.com | 75¢ County, Fairhope at odds yet Baldwin again on county road repairs schools By CLIFF MCCOLLUM message boards to County projects. moving [email protected] Road 32 near the intersec- The list includes the fol- tion with Highway 181 lowing: Tensions have once displaying a message to • CR48 just West of Bo- again flared between the motorists and the city hemian Hall Rd forward Baldwin County Com- itself: “Delays caused by According to notes mission and the city of Fairhope Utility. Call 928- from the Baldwin County Academic plan has 4 Fairhope’s utilities depart- 2136.” Highway Department: major components ment following continued The county said several “This site is currently discussions and problems roads, including County open to the public. We By CLIFF MCCOLLUM involving needed upgrades Road 32, have been held have received a quote from [email protected] to county roads on the up for far too long. County Fairhope Water & Sewer PHOTO BY CLIFF MCCOLLUM city’s borders. officials said the holdup to relocate this conflict. During a recent special called County officials moved message boards along Late Tuesday afternoon, Baldwin County Board of Edu- County Road 32 that urged residents upset has been utility line re- The City of Fairhope has by construction delays to contact the City of the county moved the locations near or around the utility agreement and cation work session, Baldwin Fairhope’s utilities department. highway department’s the various uncompleted SEE ROADS, PAGE 25 County Schools Academic Dean Joyce Woodburn laid out an academic plan for the board members comprised of four major components. -

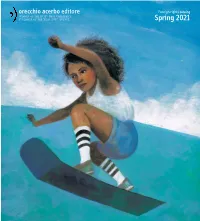

Orecchio Acerbo Rights List Spring 2021

orecchio acerbo editore Foreign rights catalog Winner of the BoP · Best Children’s PuBlisher of the Year 2017, euroPe Spring 2021 picture books daybrEak NEW by Daniel Fehr illustrations Elena Rotondo for children 4 years and older pp. 28 | cm. 23 x 21 ISBN 9788832070651 | July 2021 today NEW by Daniel Fehr big quEstioNs | grEat advENturEs illustrations Simone Rea WaitiNg for Walt for children 4 years and older by Daniel Fehr The story is about a young boy and his father. pp. 64 | cm. 17 x 24 illustrations Maja Celjia In the middle of the night they leave their house. ISBN 9788832070590 | April 2021 for children 5 years and older For the boy it is the first time that he leaves home pp. 32 | cm. 24 x 32 | May 2020 at this time of the night when normally uNdEr thE gazE of timE | rEcouNtiNg thE prEsENt he is asleep. As they walk through the forest storiEs of thE visioNary aNd thE absurd laughtEr aNd smilEs the flashlight of the boy “turns on” part A father who is leaving. Two brothers. A long wait. of the vegetation and at the same time the rest But together it is easier, together it is easy disappear. He turns off the flashlight and “turns on” to be strong. The older brother reads books Two kids are waiting for Walt. But who is Walt? all his senses: he experiences the darkness, to the younger one who can’t read yet but can And, if Walt was there with them, what would the sounds of the forest, the sound of his father, at least choose the book; then they go together they all do together? They would have a lot the roughness of the ground, the smells… on a secret mission: is every mission of spies of fun, because when he is there he always He dares not ask for the space and time secret? Then one goes to play football, the other has crazy ideas. -

The Other Side of the Lens-Exhibition Catalogue.Pdf

The Other Side of the Lens: Lewis Carroll and the Art of Photography during the 19th Century is curated by Edward Wakeling, Allan Chapman, Janet McMullin and Cristina Neagu and will be open from 4 July ('Alice's Day') to 30 September 2015. The main purpose of this new exhibition is to show the range and variety of photographs taken by Lewis Carroll (aka Charles Dodgson) from topography to still-life, from portraits of famous Victorians to his own family and wide circle of friends. Carroll spent nearly twenty-five years taking photographs, all using the wet-collodion process, from 1856 to 1880. The main sources of the photographs on display are Christ Church Library, the Metropolitan Museum, New York, National Portrait Gallery, London, Princeton University and the University of Texas at Austin. Visiting hours: Monday: 2:00 pm - 4.30 pm; Tuesday - Thursday: 10.00 am - 1.00 pm; 2:00 pm - 4.30 pm; Friday: 10:00 am - 1.00 pm. Framed photographs on loan from Edward Wakeling Photographic equipment on loan from Allan Chapman Exhibition catalogue and poster by Cristina Neagu 2 The Other Side of the Lens Lewis Carroll and the Art of Photography ‘A Tea Merchant’, 14 July 1873. IN 2155 (Texas). Tom Quad Rooftop Studio, Christ Church. Xie Kitchin dressed in a genuine Chinese costume sitting on tea-chests portraying a Chinese ‘tea merchant’. Dodgson subtitled this as ‘on duty’. In a paired image, she sits with hat off in ‘off duty’ pose. Contents Charles Lutwidge Dodgson and His Camera 5 Exhibition Catalogue Display Cases 17 Framed Photographs 22 Photographic Equipment 26 3 4 Croft Rectory, July 1856. -

Popular Fiction 1814-1939: Selections from the Anthony Tino Collection

POPULAR FICTION, 1814-1939 SELECTIONS FROM THE ANTHONY TINO COLLECTION L.W. Currey, Inc. John W. Knott, Jr., Bookseller POPULAR FICTION, 1814-1939 SELECTIONS FROM THE THE ANTHONY TINO COLLECTION WINTER - SPRING 2017 TERMS OF SALE & PAYMENT: ALL ITEMS subject to prior sale, reservations accepted, items held seven days pending payment or credit card details. Prices are net to all with the exception of booksellers with have previous reciprocal arrangements or are members of the ABAA/ILAB. (1). Checks and money orders drawn on U.S. banks in U.S. dollars. (2). Paypal (3). Credit Card: Mastercard, VISA and American Express. For credit cards please provide: (1) the name of the cardholder exactly as it appears on your card, (2) the billing address of your card, (3) your card number, (4) the expiration date of your card and (5) for MC and Visa the three digit code on the rear, for Amex the for digit code on the front. SALES TAX: Appropriate sales tax for NY and MD added. SHIPPING: Shipment cost additional on all orders. All shipments via U.S. Postal service. UNITED STATES: Priority mail, $12.00 first item, $8.00 each additional or Media mail (book rate) at $4.00 for the first item, $2.00 each additional. (Heavy or oversized books may incur additional charges). CANADA: (1) Priority Mail International (boxed) $36.00, each additional item $8.00 (Rates based on a books approximately 2 lb., heavier books will be price adjusted) or (2) First Class International $16.00, each additional item $10.00. (This rate is good up to 4 lb., over that amount must be shipped Priority Mail International). -

Reply to Donald Rackin's Review of in the Shadow of the Dreamchild

Reply to Donald Rackin’s review of In the Shadow of the Dreamchild A number of years ago, the noted Carrollian Donald Rackin wrote a scathing review of In The Shadow Of The Dreamchild IN VICTORIAN STUDIES,(VOL. 43 no. 4). The journal refused me the right to reply, so I did so on the web... Mr Rackin's review is largely (I think he would agree), a sweeping and wholesale condemnation of my work in broad, non-specific strokes. In the Shadow of the Dreamchild is, he says, “difficult to take seriously”. He adds that it is “feebly documented”, “tendentious”, unreliable and inaccurate. He claims that I „misrepresent‟ my material both overtly and „insidiously‟. This is fairly uncompromising. He does, however, offer one opening comment on which we can both agree: If Leach's contentions were valid, our understanding of Dodgson, his particular upper-middle-class milieu, and even his literary and photographic achievements, would require substantial revision I wholly accept this. If – and I stress the „if‟ – I am correct in my contention that biography has seriously misrepresented the documentary reality of Charles Dodgson's life, and if those manifold inaccuracies and „myths‟ (as I have termed them) can be proved to exist and to diverge markedly from the documentary reality, then indeed our understanding of Dodgson would require very „substantial revision‟ indeed. So, the vital question would seem to be – am I correct? Mr Rackin would have his readers believe that the very idea is ridiculous. But in truth, all we need to do is review Carroll's biographical history, and we discover all the numerous errors and flights of fancy that combined to create the present image of Lewis Carroll. -

VI Conclusion

Chapter - VI Conclusion Chapter VI Conclusion Crowley's earliest books—The Deep, Beasts, and Engine Summer (collected as Three Novels)-visit imaginary planets and the far future. In them he comes across as an ambitious author who would merely overheard rumours about science fiction, then decided to put theory into practice. These stories, clever and precious, read like gauzy pencil sketches for his immensely more densely painted large canvases. It seems to be Crowley has used Heroic fantasy in his two novels ‘THE DEEP ’ and ‘ENGINE SUMMER ’ while science fantasy in ‘BEASTS’. ‘The Deep’ and ‘Engine summer’ are based on the heroic characters that work in different way for society. ‘The Deep’ is about the journey of the Visitor from the Sky to the Deep. Visitor, who is a person with fantasy characters, lives with Reds-one of the societies from the plot of ‘The Deep’. On the other hand ‘Engine Summer’ is about a boy namely Rush that speaks who first goes in search of his love-Onee A Day, but finally wanted to become a saint. During his journey he becomes fond of truthful speaking and hence is a hero of society. However, ‘Beasts' is about the genetically engineered animals lion-headed man Painter and fox-headed man Reynard who are trying to survive against hunting and elimination measures of Political forces. The landscape of The Deep is an interesting one. Two societies Reds and Blacks are fighting for the crown while the Just are the criminals and Grays are wise men with justice. The novel shows some sort of war happening between Reds and Black where the hero of the Novel-Visitor tries to solve the problem of crown with the help of Grays. -

Chapter 1: Mattes and Compositing Defined Chapter 2: Digital Matting

Chapter 1: Mattes and Compositing Defined Chapter 2: Digital Matting Methods and Tools Chapter 3: Basic Shooting Setups Chapter 4: Basic Compositing Techniques Chapter 5: Simple Setups on a Budget Chapter 6: Green Screens in Live Broadcasts Chapter 7: How the Pros Do It one PART 521076c01.indd 20 1/28/10 8:50:04 PM Exploring the Matting Process Before you can understand how to shoot and composite green screen, you first need to learn why you’re doing it. This may seem obvious: you have a certain effect you’re trying to achieve or a series of shots that can’t be done on location or at the same time. But to achieve good results from your project and save yourself time, money, and frustration, you need to understand what all your options are before you dive into a project. When you have an understanding of how green screen is done on all levels you’ll have the ability to make the right decision for just about any project you hope to take on. 521076c01.indd 1 1/28/10 8:50:06 PM one CHAPTER 521076c01.indd 2 1/28/10 8:50:09 PM Mattes and Compositing Defined Since the beginning of motion pictures, filmmakers have strived to create a world of fantasy by combining live action and visual effects of some kind. Whether it was Walt Disney creating the early Alice Comedies with cartoons inked over film footage in the 1920s or Ray Harryhausen combining stop-motion miniatures with live footage for King Kong in 1933, the quest to bring the worlds of reality and fantasy together continues to evolve. -

Annihilating Nihilistic Nonsense Tim Burton Guts Lewis Carroll’S Jabberwocky

Annihilating Nihilistic Nonsense Tim Burton Guts Lewis Carroll’s Jabberwocky Alice in Wonderland seems to beg for a morbid interpretation. Whether it's Marilyn Manson's "Eat Me, Drink Me," the video game "American McGee's Alice," or Svankmajer's "Alice" and "Jabberwocky," artists love bringing out the darker elements of Alice’s adventures as she wanders among creepy creatures. The 2010 Tim Burton film is the latest twisted adaptation, featuring an older Alice that slays the Jabberwocky. However, unlike the other adaptations, Burton’s adaptation draws most of its grim outlook by gutting Alice in Wonderland of its fundamental core - its nonsense. Alice in Wonderland uses nonsense to liberate, offering frightening amounts of freedom through its playful use of nonsense. However, Burton turns this whimsy into menacing machinations - he pretends to use nonsense for its original liberating purpose but actually uses it for adult plots and preset paths. Burton takes the destructive power of Alice’s insistence for order and amplifies it dramatically, completely removing its original subversive release from societal constraints. Under the façade of paying tribute to Carroll’s whimsical nonsense verse, Burton directly removes nonsense’s anarchic freedom and replaces it with a destructive commitment to sense. This brutal change to both plot and structure turns Alice into a mindless juggernaut, slaying not only the Jabberwock, but also the realm of nonsense, non-linear narrative and real world empires. At first, nonsense in Lewis Carroll’s books seems to just a light-hearted play with language. Even before we come into Wonderland, the idea of nonsense as just a simple child’s diversion is given by the epigraph.