"6$ ."*@CL9@CJ#L "6&$CG@%LC$ A=-L@68L&@@*>C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Potential of the Implementation of Demand-Side Management at the Theunissen-Brandfort Pumps Feeder

POTENTIAL OF THE IMPLEMENTATION OF DEMAND-SIDE MANAGEMENT AT THE THEUNISSEN-BRANDFORT PUMPS FEEDER by KHOTSOFALO CLEMENT MOTLOHI Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree MAGISTER TECHNOLOGIAE: ENGINEERING: ELECTRICAL In the Faculty of Engineering, Information & Communication Technology: School of Electrical & Computer Systems Engineering At the Central University of Technology, Free State Supervisor: Mr L Moji, MSc. (Eng) Co- supervisor: Prof. LJ Grobler, PhD (Eng), CEM BLOEMFONTEIN NOVEMBER 2006 i PDF created with pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com ii DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENT WORK I, KHOTSOFALO CLEMENT MOTLOHI, hereby declare that this research project submitted for the degree MAGISTER TECHNOLOGIAE: ENGINEERING: ELECTRICAL, is my own independent work that has not been submitted before to any institution by me or anyone else as part of any qualification. Only the measured results were physically performed by TSI, under my supervision (refer to Appendix I). _______________________________ _______________________ SIGNATURE OF STUDENT DATE PDF created with pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com iii Acknowledgement My interest in the energy management study concept actually started while reading Eskom’s journals and technical bulletins about efficient-energy utilisation and its importance. First of all I would like to thank ALMIGHTY GOD for making me believe in MYSELF and giving me courage throughout this study. I would also like to thank the following people for making this study possible. I would like to express my sincere gratitude and respect to both my supervisors Mr L Moji and Prof. LJ Grobler who is an expert and master of the energy utilisation concept and also for both their positive criticism and the encouragement they gave me throughout this study. -

Remembrance African Activist Archive Project Documenting

Remembrance African Activist Archive Project Documenting Apartheid: 30 Years of Filming South Africa By Peter Davis During April 2004 and beyond we were constantly reminded that this is the tenth anniversary of the first democratic all-race elections in South Africa. I was shocked by the realization that last year also marked the thirtieth anniversary of my first visit to that country, of my first experience with apartheid. After that first trip in 1974 as part of an African tour I was doing for the American NGO, Care, I was to devote a large part of my working life to the anti-apartheid struggle. For those of us who were involved in that struggle, it was such an everyday part of life that it is hard to grasp that there is already a generation out there that does not know the meaning of “apartheid”. The struggle against apartheid took many forms, from protests, strikes, sabotage, defiance, guerrilla warfare within the country to boycotts, bans, United Nations resolutions, rock concerts, and arms and money smuggling and espionage outside. Apartheid, which was institutionalized by the coming to power of the white National Party in 1948, lasted as long as it did, against the condemnation of the world, because it had powerful friends. Chief among these were the United States, which saw a South Africa governed by whites as a useful ally in the Cold War; a Britain whose ruling class had close links with South African capital; and German, French, Israeli and Taiwanese commercial interests that extended even to sales of weapons and nuclear technology to the apartheid regime. -

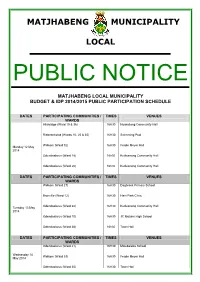

Matjhabeng Municipality Local

MATJHABENG MUNICIPALITY LOCAL PUBLIC NOTICE MATJHABENG LOCAL MUNICIPALITY BUDGET & IDP 2014/2015 PUBLIC PARTICIPATION SCHEDULE DATES PARTICIPATING COMMUNITIES / TIMES VENUES WARDS Allanridge (Ward 19 & 36) 16H30 Nyakallong Community Hall Riebeeckstad (Wards 10, 25 & 35) 16H30 Swimming Pool Welkom (Ward 32) 16H30 Ferdie Meyer Hall Monday 12 May 2014 Odendaalsrus (Ward 18) 16h30 Kutlwanong Community Hall Odendaalsrus (Ward 20) 16h30 Kutlwanong Community Hall DATES PARTICIPATING COMMUNITIES / TIMES VENUES WARDS Welkom (Ward 27) 16H30 Dagbreek Primary School Bronville (Ward 12) 16H30 Hani Park Clinic Odendaalsrus (Ward 22) 16H30 Kutlwanong Community Hall Tuesday 13 May 2014 Odendaalsrus (Ward 10) 16H30 JC Motumi High School Odendaalsrus (Ward 36) 16h30 Town Hall DATES PARTICIPATING COMMUNITIES / TIMES VENUES WARDS Odendaalsrus (Ward 21) 16H30 Malebaleba School Wednesday 14 Welkom (Ward 33) 16H30 Ferdie Meyer Hall May 2014 Odendaalsrus (Ward 35) 16H30 Town Hall Bronville (Ward 11) 16H30 Bronville Community Hall Welkom (Ward 24) 16H30 Reahola Housing Units DATES PARTICIPATING COMMUNITIES / TIMES VENUES WARDS Bronville (Ward 23) 16H30 Hani Park Church Thabong (Ward 12) 16H30 Tsakani School Thursday 15 May Thabong (Ward 30) 16H30 Thabong Primary School 2014 Thabong (Ward 31) 16H30 Thabong Community Centre Thabong (Ward 28) 16H30 Thembekile School DATES PARTICIPATING COMMUNITIES / TIMES VENUES WARDS Thabong (Ward 26) 16H30 Bofihla School Thabong (Ward 29) 16H30 Lebogang School Monday 19 May 2014 Thabong Far East (Ward 25) 16H30 Matshebo School -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

General Observations About the Free State Provincial Government

A Better Life for All? Fifteen Year Review of the Free State Provincial Government Prepared for the Free State Provincial Government by the Democracy and Governance Programme (D&G) of the Human Sciences Research Council. Ivor Chipkin Joseph M Kivilu Peliwe Mnguni Geoffrey Modisha Vino Naidoo Mcebisi Ndletyana Susan Sedumedi Table of Contents General Observations about the Free State Provincial Government........................................4 Methodological Approach..........................................................................................................9 Research Limitations..........................................................................................................10 Generic Methodological Observations...............................................................................10 Understanding of the Mandate...........................................................................................10 Social attitudes survey............................................................................................................12 Sampling............................................................................................................................12 Development of Questionnaire...........................................................................................12 Data collection....................................................................................................................12 Description of the realised sample.....................................................................................12 -

The Free State, South Africa

Higher Education in Regional and City Development Higher Education in Regional and City Higher Education in Regional and City Development Development THE FREE STATE, SOUTH AFRICA The third largest of South Africa’s nine provinces, the Free State suffers from The Free State, unemployment, poverty and low skills. Only one-third of its working age adults are employed. 150 000 unemployed youth are outside of training and education. South Africa Centrally located and landlocked, the Free State lacks obvious regional assets and features a declining economy. Jaana Puukka, Patrick Dubarle, Holly McKiernan, How can the Free State develop a more inclusive labour market and education Jairam Reddy and Philip Wade. system? How can it address the long-term challenges of poverty, inequity and poor health? How can it turn the potential of its universities and FET-colleges into an active asset for regional development? This publication explores a range of helpful policy measures and institutional reforms to mobilise higher education for regional development. It is part of the series of the OECD reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development. These reviews help mobilise higher education institutions for economic, social and cultural development of cities and regions. They analyse how the higher education system T impacts upon regional and local development and bring together universities, other he Free State, South Africa higher education institutions and public and private agencies to identify strategic goals and to work towards them. CONTENTS Chapter 1. The Free State in context Chapter 2. Human capital and skills development in the Free State Chapter 3. -

Uys Van Heerden

FREE DECEMBER 2016 • JANUARY 2017 SENWES EQUIPMENT AND JOHN DEERE’S GATOR WINNER Senwes Equipment and JCB – A perfect match Win with Nation in Conversation FOCUS ON Welkom & Odendaalsrus An introduction to OneAgri CHRISTMAS PERFORMANCE AND PRODUCTIVITY. SPECIAL OFFERS REDUCED RATES POSTPONED INSTALMENTS *Terms and conditions apply My choice, my Senwes. At Senwes Equipment we know what our clients want and we make sure that they get it. As the exclusive John Deere dealer we guarantee your access to the latest developments. PLEASEWe ensure CONTACTthat you have YOUR the best that money has to oer. NEAREST SENWES EQUIPMENT BRANCH FOR MORE INFO. CONTENTS ••••••• 8 31 4 CONTENTS EDITOR'S LETTER 20 Management of variables in a 2 It is raining! farming system with the assistance ON THE COVER PAGE of precision farming WHAT A YEAR 2016 has been for GENERAL 23 Meet Estelle ‘Senwes’ the newly established trademark of 3 Cartoon: Pieter & Tshepo 25 Herman is your Senwes Man – Senwes Equipment! With prize upon 3 Heard all over A grain marketing advisor with the prize they really created a Christmas 15 Christmas messages full package spirit. 26 How the handling of grain On the front page we have Gert MAIN ARTICLE changed over time? Part I 4 JCB and Senwes Equipment: A (Gerlu) Roos from Wonderfontein, 28 Branch manager Potchefstroom who won the second leg of the WIN perfect match! – Ruan brings colour to Potch BIG with Senwes Equipment and John Deere competition in Novem- 30 Utilise our Digital Platforms AREA FOCUS ber. In the process he won a John in an optimal manner 8 Welkom and Odendaalsrus Deere Gator 855D to the value of – In Circles! 46 Gert Roos wins R230 000 John R230 000, a wonderful gift, just in Deere Gator 855D time for Christmas. -

WELKOM Annual Meeting of the American Comparative Literature Association

ACLA 2017 ACLA WELKOM Annual Meeting of the American Comparative Literature Association ACLA 2017 | Utrecht University TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome and Acknowledgments ...............................................................................................4 Welcome from Utrecht Mayor’s Office .....................................................................................6 General Information ................................................................................................................... 7 Conference Schedule ................................................................................................................. 14 Biographies of Keynote Speakers ............................................................................................ 18 Film Screening, Video Installation and VR Poetry ............................................................... 19 Pre-Conference Workshops ...................................................................................................... 21 Stream Listings ..........................................................................................................................26 Seminars in Detail (Stream A, B, C, and Split Stream) ........................................................42 Index......................................................................................................................................... 228 CFP ACLA 2018 Announcement ...........................................................................................253 Maps -

SOUTH AFRICA Africa & Asia Pacific | Cape Town, Knysna, Kapama Game Reserve

SOUTH AFRICA Africa & Asia Pacific | Cape Town, Knysna, Kapama Game Reserve South Africa AFRICA & ASIA PACIFIC | Cape Town, Knysna, Kapama Game Reserve Season: 2021 Adult-Exclusive 10 DAYS 23 MEALS 18 SITES Experience the beauty of the people, cultures and landscapes of South Africa on this amazing Adventures by Disney vacation where you’ll thrill to the majesty of seeing wild animals in their natural environments, view Cape Town from atop the awe-inspiring Table Mountain and travel to the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of the continent. SOUTH AFRICA Africa & Asia Pacific | Cape Town, Knysna, Kapama Game Reserve Trip Overview 10 DAYS / 9 NIGHTS ACCOMMODATIONS 3 LOCATIONS Table Bay Hotel Cape Town, Knysna, Kapama Pezula Hotel Game Reserve Kapama River Lodge AGES FLIGHT INFORMATION 23 MEALS Minimum Age: 6 Arrive: Cape Town (CPT) 9 Breakfasts, 8 Lunches, 6 Suggested Age: 8+ Return: Johannesburg (JNB) Dinners Adult Exclusive: Ages 18+ 3 Internal Flights Included SOUTH AFRICA Africa & Asia Pacific | Cape Town, Knysna, Kapama Game Reserve DAY 1 CAPE TOWN Activities Highlights: No Meals Included Arrive in Cape Town Table Bay Hotel Arrive at Cape Town Welkom! Upon exiting customs, be greeted by an Adventures by Disney representative who escorts you to your transfer vehicle. Relax as the driver assists with your luggage and takes you to the Table Bay Hotel. Table Bay Hotel Unwind from your journey as your Adventure Guide checks you into this spacious, sophisticated, full-service hotel located on the Victoria & Alfred Waterfront. Ask your Adventure Guide for suggestions about exploring Cape Town on your own. -

Spatial Transformation: Are Intermediate Cities Different? South African Cities Network: Johannesburg

CENTRE FOR DEVELOPMENT SUPPORT SENTRUM VIR ONTWIKKELINGSTEUN ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Lead authors: Lochner Marais (University of the Free State) Danie Du Plessis (Stellenbosch University) Case study authors: Drakenstein: Ronnie Donaldson (Stellenbosch University) King Sabata Dalindyebo: Esethu Ndzamela (Nelson Mandela University) and Anton De Wit (Nelson Mandela University Lephalale: Kgosi Mocwagae (University of the Free State) Matjhabeng: Stuart Denoon-Stevens (University of the Free State) Mahikeng: Verna Nel (University of the Free State) and James Drummond (North West University) Mbombela: Maléne Campbell (University of the Free State) Msunduzi: Thuli Mphambukeli (University of the Free State) Polokwane: Gemey Abrahams (independent consultant) Rustenburg: John Ntema (University of South Africa) Sol Plaatje: Thomas Stewart (University of the Free State) Stellenbosch: Danie Du Plessis (Stellenbosch University) Manager: Geci Karuri-Sebina Editing by Write to the Point Design by Ink Design Photo Credits: Page 2: JDA/SACN Page 16: Edna Peres/SACN Pages 18, 45, 47, 57, 58: Steve Karallis/JDA/SACN Page 44: JDA/SACN Page 48: Tanya Zack/SACN Page 64: JDA/SACN Suggested citation: SACN. 2017. Spatial Transformation: Are Intermediate Cities Different? South African Cities Network: Johannesburg. Available online at www.sacities.net ISBN: 978-0-6399131-0-0 © 2017 by South African Cities Network. Spatial Transformation: Are Intermediate Cities Different? is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/. 2 SPATIAL TRANSFORMATION: ARE INTERMEDIATE CITIES DIFFERENT? Foreword As a network whose primary stakeholders are the largest cities, the South African Cities Network (SACN) typically focuses its activities on the “big” end of the urban spectrum (essentially, mainly the metropolitan municipalities). -

Public Libraries in the Free State

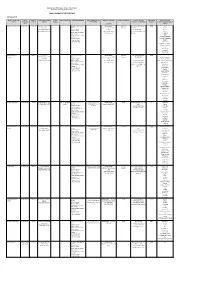

Department of Sport, Arts, Culture & Recreation Directorate Library and Archive Services PUBLIC LIBRARIES IN THE FREE STATE MOTHEO DISTRICT NAME OF FRONTLINE TYPE OF LEVEL OF TOWN/STREET/STREET STAND GPS COORDINATES SERVICES RENDERED SPECIAL SERVICES AND SERVICE STANDARDS POPULATION SERVED CONTACT DETAILS REGISTERED PERIODICALS AND OFFICE FRONTLINE SERVICE NUMBER NUMBER PROGRAMMES CENTER/OFFICE MANAGER MEMBERS NEWSPAPERS AVAILABLE IN OFFICE LIBRARY: (CHARTER) Bainsvlei Public Library Public Library Library Boerneef Street, P O Information and Reference Library hours: 446 142 Ms K Niewoudt Tel: (051) 5525 Car SA Box 37352, Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 446-3180 Fair Lady LANGENHOVENPARK, Outreach Services 17:00 Fax: (051) 446-1997 Finesse BLOEMFONTEIN, 9330 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 karien.nieuwoudt@mangau Hoezit Government Info Services Sat: 8:30-12:00 ng.co.za Huisgenoot Study Facilities Prescribed books of tertiary Idees Institutions Landbouweekblad Computer Services: National Geographic Internet Access Rapport Word Processing Rooi Rose SA Garden and Home SA Sports Illustrated Sarie The New Age Volksblad Your Family Bloemfontein City Public Library Library c/o 64 Charles Information and Reference Library hours: 443 142 Ms Mpumie Mnyanda 6489 Library Street/West Burger St, P Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 051 405 8583 Africa Geographic O Box 1029, Outreach Services 17:00 Architect and Builder BLOEMFONTEIN, 9300 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 Tel: (051) 405-8583 Better Homes and Garden n Government Info -

Mean Streets: Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa

Mean Streets Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa Published by the Southern African Migration Programme (SAMP), the African Centre for Cities (ACC) and the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) Southern African Migration Programme, International Migration Research Centre Balsillie School of International Affairs, 67 Erb Street West, Waterloo, Ontario N2L 6C2, Canada African Centre for Cities, University of Cape Town, Environmental & Geographical Science Building, Upper Campus, Rondebosch, 7701, South Africa International Development Research Centre, 160 Kent St, Ottawa, Canada K1P 0B2 and Eaton Place, 3rd floor, United Nations Crescent, Gigiri, Nairobi, Kenya ISBN 978-1-920596-11-8 © SAMP 2015 First published 2015 Production, including editing, design and layout, by Bronwen Dachs Muller Cover by Michiel Botha Cover photograph by Alon Skuy/The Times. The photograph shows Soweto residents looting a migrant-owned shop in a January 2015 spate of attacks in South Africa Index by Ethné Clarke Printed by MegaDigital, Cape Town All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission from the publishers. Mean Streets Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa Edited by Jonathan Crush Abel Chikanda Caroline Skinner Acknowledgements The editors would like to acknowledge the financial and programming support of the Inter- national Development Research Centre (IDRC), which funded the research of the Growing Informal Cities Project and the Workshop on Urban Informality and Migrant Entrepre- neurship in Southern African Cities hosted by SAMP and the African Centre for Cities in Cape Town in February 2014. Many of the chapters in this volume were first presented at this workshop.