Spatial Transformation: Are Intermediate Cities Different? South African Cities Network: Johannesburg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SAHRA-Annual-Report-2007.Pdf

SAHRA Ann Rep Cover 2007 repro Monday, August 27, 2007 1:21:22 PM Table of Contents SAHRA’S VISION AND MISSION STATEMENT 2 LETTER FROM THE CHAIRPERSON 3 THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER’S FOREWORD AND MESSAGE 4 APPLICABLE ACTS AND OTHER INFORMATION 7 STATEMENT OF RESPONSIBILITY 8 CORPORATE AFFAIRS 9 Human Resources Management 10 Information and Auxiliary Services 25 HERITAGE RESOURCES MANAGEMENT 27 Head Office Units Archaeology, Palaeontology and Meteorites Unit 28 Architectural Heritage Landscape Unit 34 Burial Grounds and Graves Unit 38 Grading and Declarations Unit 44 Heritage Objects Unit 48 Living Heritage Unit 54 Maritime Archaeology Unit 62 National Inventory Unit 72 Provincial Offices Eastern Cape 76 Free State 80 Gauteng 80 Kwa-Zulu Natal 92 Limpopo 94 Mpumalanga 98 North West 102 Northern Cape 110 Western Cape 116 LEGAL UNIT 128 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 131 SAHRA OFFICES AND STAFF 161 SAHRA’S VISION SAHRA’s vision is to provide for the identification, conservation, protection and promotion of our heritage resources for present and future generations. SAHRA’S MISSION As custodians of our national estate our mission is: ° to coordinate and monitor the identification of our national heritage resources; ° to set norms and standards and maintain the management of heritage resources nationally; ° to encourage co-operative conservation of our national estate; ° to enable and facilitate the development of provincial structures; ° to control the export and import of nationally significant heritage resources; ° to develop policy initiative for the promotion and management of our heritage; ° to nurture an holistic celebration of our history; ° to set national policy for heritage resources management, i.e. -

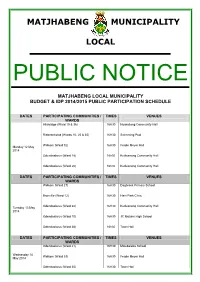

Matjhabeng Municipality Local

MATJHABENG MUNICIPALITY LOCAL PUBLIC NOTICE MATJHABENG LOCAL MUNICIPALITY BUDGET & IDP 2014/2015 PUBLIC PARTICIPATION SCHEDULE DATES PARTICIPATING COMMUNITIES / TIMES VENUES WARDS Allanridge (Ward 19 & 36) 16H30 Nyakallong Community Hall Riebeeckstad (Wards 10, 25 & 35) 16H30 Swimming Pool Welkom (Ward 32) 16H30 Ferdie Meyer Hall Monday 12 May 2014 Odendaalsrus (Ward 18) 16h30 Kutlwanong Community Hall Odendaalsrus (Ward 20) 16h30 Kutlwanong Community Hall DATES PARTICIPATING COMMUNITIES / TIMES VENUES WARDS Welkom (Ward 27) 16H30 Dagbreek Primary School Bronville (Ward 12) 16H30 Hani Park Clinic Odendaalsrus (Ward 22) 16H30 Kutlwanong Community Hall Tuesday 13 May 2014 Odendaalsrus (Ward 10) 16H30 JC Motumi High School Odendaalsrus (Ward 36) 16h30 Town Hall DATES PARTICIPATING COMMUNITIES / TIMES VENUES WARDS Odendaalsrus (Ward 21) 16H30 Malebaleba School Wednesday 14 Welkom (Ward 33) 16H30 Ferdie Meyer Hall May 2014 Odendaalsrus (Ward 35) 16H30 Town Hall Bronville (Ward 11) 16H30 Bronville Community Hall Welkom (Ward 24) 16H30 Reahola Housing Units DATES PARTICIPATING COMMUNITIES / TIMES VENUES WARDS Bronville (Ward 23) 16H30 Hani Park Church Thabong (Ward 12) 16H30 Tsakani School Thursday 15 May Thabong (Ward 30) 16H30 Thabong Primary School 2014 Thabong (Ward 31) 16H30 Thabong Community Centre Thabong (Ward 28) 16H30 Thembekile School DATES PARTICIPATING COMMUNITIES / TIMES VENUES WARDS Thabong (Ward 26) 16H30 Bofihla School Thabong (Ward 29) 16H30 Lebogang School Monday 19 May 2014 Thabong Far East (Ward 25) 16H30 Matshebo School -

Tyalara -Qunu 132 Kv Power Line and Associated Infrastructure

ESKOM HOLDINGS SOC (PTY) LTD DRAFT BASIC ASSESSMENT REPORT PROPOSED CONSTRUCTION OF ESKOM TYALARA -QUNU 132 KV POWER LINE AND ASSOCIATED INFRASTRUCTURE SEPTEMBER 2013 J31096 GIBB Environmental 9 Pearce Road East London, South Africa 5241 www.gibb.co.za Contact : Mervin Olivier Tel: +27 43 706 3656 Fax: +27 43 721 0141 [email protected] DRAFT BASIC ASSESSMENT REPORT PROPOSED CONSTRUCTION OF ESKOM TYALARA-QUNU 132KV POWER LINE AND ASSOCIATED INFRASTRUCTURE CONTENTS Chapter Description Page SECTION A: ACTIVITY INFORMATION ......................................................................................... 3 SECTION B: SITE/AREA/PROPERTY DESCRIPTION ................................................................... 29 SECTION C: PUBLIC PARTICIPATION ........................................................................................ 48 SECTION D: IMPACT ASSESSMENT .......................................................................................... 51 SECTION E: RECOMMENDATION OF PRACTITIONER ............................................................... 79 SECTION F: APPENDIXES ......................................................................................................... 81 APPENDICES Appendix A1: 21-Digit Site Reference Appendix A2: 250m Coordinates Appendix A3: Locality Map Appendix A4: Vegetation Map Appendix A5: Terrestrial Critical Biodiversity Areas Appendix A6: Aquatic Critical Biodiversity Areas Appendix A7: Route Deviation around Nelson Mandela’s Property Appendix B: Photographs Appendix C1: Facility -

Sub-National Governments and Foreign Policy: the Case of the Limpopo Province in South Africa

SUB-NATIONAL GOVERNMENTS AND FOREIGN POLICY: THE CASE OF THE LIMPOPO PROVINCE IN SOUTH AFRICA by Vhulenda Edna Matshili Submitted in accordance with the requirements of the degree of Masters of Arts in the subject Politics at the University of South Africa Supervisor: Professor Jo-Ansie van Wyk 2013 DECLARATION I declare that “Sub-national governments and foreign policy: The case of the Limpopo province in South Africa ” is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. ________________________ _____________________ Signature Date (Miss Vhulenda Edna Matshili) i ABSTRACT The aim of this study is to analyse and describe the role of sub-national governments (SNG’s) in foreign policy and how the conduct of diplomacy has developed in the South African context, and to assess why and how provinces engage in this phenomenon. The theoretical approach to this study is embedded in neo- functionalism. In order to illustrate this, the South African province, the Limpopo Province is used as an illustrative case study. In particular, the study will analyse the role of the International Relations Unit (IRU) within the Office of the Premier (OtP) in the Limpopo Province as a case study. Limpopo is the main focus of this study because it, inter alia, borders on three sovereign states (Botswana, Mozambique and Zimbabwe) which place the province in a good position to engage in international relations, mutual intentions and friendly relations with its neighbouring and other distant countries. The results of this study is that provinces have become important foreign policy and international relations actors in the area of low politics; however the national government remains as the main actor in the international relations and foreign policy making process. -

Proposed Coal-Fired Power Stations and Associated Infrastructure in the Waterberg, Limpopo

Report No: [4793A/402719] ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT PROCESS: PROPOSED COAL-FIRED POWER STATIONS AND ASSOCIATED INFRASTRUCTURE IN THE WATERBERG, LIMPOPO FINAL SCOPING REPORT March 2009 LEAD CONSULTANT PROPONENT Ninham Shand (Pty) Ltd. Eskom Holdings Ltd. 81 Church Street Eskom Generation PO Box 1347 Megawatt Park Cape Town Maxwell Drive 8000 Sandton, 2199 Tel: (021) 481 2400 Tel: (011) 800 3501 Fax: (021) 424 5588 Fax : (011) 800 5140 Email: [email protected] Website : www.eskom.co.za PROPOSED COAL-FIRED POWER STATIONS IN THE WATERBERG, LIMPOPO: SCOPING REPORT Page i PROJECT DETAILS DEAT REFERENCE NO. : 12/12/20/1255 TITLE : FINAL SCOPING REPORT AUTHORS : Louise Corbett, Ashwin West, Brett Lawson SUBCONSULTANTS : AirShed Planning Professionals Golder Associates Groundwater Consulting Services InfoTox Ivuzi Johnny van Schalkwyk (Private Consultant) Jongens Keet Associates Makecha Development Association Ndodana Consulting Engineers Ptersa Environmental Management Consultants Riscom Smith, Summers, Ndlovu Associates Strategic Environmental Focus Urban-Econ Zitholele Consulting CLIENT : Eskom Holdings Limited (Generation Division) REPORT STATUS : Final REPORT NUMBER : 4793A/402719 REPORT DATE : 31 March 2009 ................................................ ………........................................... LOUISE CORBETT ASHWIN WEST (Pr. Sci Nat) Environmental Practitioner Associate: Environmental Discipline Group ................................................ BRETT LAWSON (Cert. EAPSA)(Pr Sci Nat) Associate: Environmental Discipline -

Management Has Reviewed the Request for Inspection of the Republic of South Africa Eskom Investment Support Project (Lbrd Loan No

BANK MANAGEMENT RESPONSE TO REQUEST FOR INSPECTION PANEL REVIEW OF THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA ESKOM INVESTMENT SUPPORT PROJECT (IBRD Loan No. 78620) Management has reviewed the Request for Inspection of the Republic of South Africa Eskom Investment Support Project (lBRD Loan No. 78620), received by the Inspection Panel on April 6, 2010 and registered on April 7, 2010 (RQI0/03). Management has prepared the following response. May 25,2010 Eskom Investment Support Project CONTENTS Abbreviations and Acronyms ......................................................................................... iii Executive Summary ......................................................................................................... iv I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................... 1 II. THE REQ VEST ....................................................................................................... 1 III. COUNTRY CONTEXT AND PROJECT BACKGROUND ............................... 2 IV. SPECIAL ISSUES ................................................................................................... 7 V. MANAGEMENT'S RESPONSE .......................................................................... 20 ANNEXES Annex 1. Claims and Responses MAPS IBRD 37886 South Africa - Eskom Investment Support Project, Request for Inspection (project area) IBRD 37853 South Africa - Eskom Investment Support Project, Request for Inspection (detail) ii Republic ofSouth Africa ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS -

Positive Actions in Turbulent Times

positive actions in turbulent times Our strategy remains unchanged and our value proposition intact. Balancing short-term needs and long-term sustainability, we have continued to renew our business basics, preserving Sasol’s robust fundamentals and delivering a solid performance in deteriorating markets. Our pipeline of growth projects remains strong, even though we have reprioritised capital spending. With our shared values as our guide, we have dealt decisively with disappointments and unprecedented challenges. We are confident that our positive actions will help us navigate the storm and emerge stronger than before. About Sasol sasol annual review and summarised financial information 2009 financial information and summarised review sasol annual Sasol is an energy and chemicals company. We convert coal and gas into liquid fuels, fuel components and chemicals through our proprietary Fischer-Tropsch (FT) processes. We mine coal in South Africa, and produce gas and condensate in Mozambique and oil in Gabon. We have chemical manufacturing and marketing operations in South Africa, Europe, the Middle East, Asia and the Americas. In South Africa, we refine imported crude oil and retail liquid fuels through our network of Sasol convenience centres. We also supply fuels to other distributors in the region and gas to industrial customers in South Africa. Based in South Africa, Sasol has operations in 38 countries and employs some 34 000 people. We continue to pursue international opportunities to commercialise our gas-to-liquids (GTL) and coal-to-liquids (CTL) technology. In partnership with Qatar Petroleum we started up our first international GTL plant, Oryx GTL, in Qatar in 2007. -

Focused and Energised About Sasol

sustainable development report 2010 focused and energised about sasol Sasol is an energy and chemicals company. We are technology driven, converting gas and coal into liquid fuels, fuel components and chemicals through our proprietary processes. We are focused on commercialising our gas-to-liquids (GTL) and coal- to-liquids (CTL) technology internationally. We mine coal in South Africa, and produce gas and condensate in Mozambique and oil in Gabon. We continue to advance our upstream oil and gas activities in Mozambique, Nigeria, Gabon, South Africa, Papua New Guinea and Australia. In South Africa, we refi ne imported crude oil and retail liquid fuels through our network of Sasol convenience centres, and supply gas to industrial customers. We also supply fuel to other distributors in the region. We have chemical manufacturing and marketing operations in South Africa, Europe, the Middle East, Asia and the Americas. Formed in 1950, Sasol has been producing liquid fuels since 1955. Sasol is listed on the JSE Limited in South Africa and the New York Stock Exchange. our vision A more detailed review of Sasol’s primary brands, products and services, its operational structure, the countries in which it operates, and the primary markets served To grow profi tably, sustainably and inclusively is provided on our website while delivering value to stakeholders http://sasolsdr.com through proprietary technology and the talent of our people in the energy GRI – 2.1 – 2.8 and chemical markets in Southern Africa and worldwide. sasol’s values The Sasol group’s vision, strategic growth drivers and daily business operations are founded on, and inspired by, six shared values: Customer focus Safety Continuous improvement We meet customers’ needs by providing We commit to eliminate all incidents Our innovative spirit drives us as we world-class service, optimal product and work to world-class safety standards. -

South African Police Service South African Police Service Annual Report 2017/2018 Annual Report 2017/2018 Part A

SOUTH AFRICAN POLICE SERVICE SOUTH AFRICAN POLICE SERVICE ANNUAL REPORT 2017/2018 ANNUAL REPORT 2017/2018 PART A A SOUTH AFRICAN POLICE SERVICE SOUTH AFRICAN POLICE SERVICE PART A ANNUAL REPORT 2017/2018 ANNUAL REPORT 2017/2018 B SOUTH AFRICAN POLICE SERVICE SOUTH AFRICAN POLICE SERVICE ANNUAL REPORT 2017/2018 ANNUAL REPORT 2017/2018 Compiled by South African Police Service (SAPS) Strategic Management Layout and Design SAPS Corporate Communication and Liaison Photographs SAPS Corporate Communication and Liaison Language Editing SAPS Strategic Management Further information on the Annual Report for the National Commissioner of the South African Police Service, for 2017/2018, can be obtained from: SAPS Strategic Management (Head Office) Telephone: 012 393 3082 RP Number: 328/2018 ISBN Number: 978-0-621-46664-5 i SOUTH AFRICAN POLICE SERVICE SOUTH AFRICAN POLICE SERVICE ANNUAL REPORT 2017/2018 ANNUAL REPORT 2017/2018 SUBMISSION OF THE ANNUAL REPORT TO THE MINISTER OF POLICE Mr BH Cele, MP MINISTER OF POLICE I have the honour of submitting the Annual Report of the Department of Police, for the period 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2018. GENERAL KJ SITOLE (SOEG) 31 August 2018 ii SOUTH AFRICAN POLICE SERVICE SOUTH AFRICAN POLICE SERVICE ANNUAL REPORT 2017/2018 ANNUAL REPORT 2017/2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART A: GENERAL INFORMATION 1 1. General Information of the Department 1 2. List of Abbreviations/Acronyms 2 3. Foreword by the Minister 6 4. Deputy Minister’s Statement 9 5. Report of the Accounting Officer 11 6. Statement of Responsibility and Confirmation of Accuracy of the Annual Report 24 7. -

Written Statement of Mxolisi Mgojo, the Chief Executive Officer Of

1 PUBLIC ENTERPRISES PORTFOLIO COMMITTEE INQUIRY INTO ESKOM, TRANSNET AND DENEL WRITTEN STATEMENT OF MXOLISI MGOJO, THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER OF EXXARO RESOURCES LIMITED INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 2 COST-PLUS MINES VERSUS COMMERCIAL MINES .......................................... 5 THE SO-CALLED “PRE-PAYMENT” FOR COAL ................................................. 9 PREJUDICE TO EXXARO’S COST-PLUS MINES AND MAFUBE ..................... 11 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 11 Arnot mine ............................................................................................................. 12 Eskom’s failure to fund land acquisition ................................................................. 12 Non-funding of operational capital at Arnot ............................................................ 14 The termination of Arnot’s CSA .............................................................................. 15 Conclusion of the Arnot matters ............................................................................. 19 Mafube mine.......................................................................................................... 19 Matla mine ............................................................................................................. 21 Non-funding of capital of R1.8 billion for mine 1 ................................................... -

2. DESCRIPTION of the PROPOSED PROJECT In

Environmental Scoping Report for the proposed establishment of a New Coal-Fired Power Station in the Lephalale Area, Limpopo Province 2. DESCRIPTION OF THE PROPOSED PROJECT In order to be able to adequately provide for the growing electricity demand, Eskom propose to construct a new power station with a maximum capacity of 4 800 MegaWatts (MW) in the Lephalale area in the vicinity of the existing Matimba Power Station. Currently the project name for the new proposed power station is Matimba B, but the name will be changed should the project be approved. The power station will be coal-fired, and source coal from local coalfields. 2.1 The Proposed Matimba B Power Station Matimba B Power Station is proposed to ultimately have a maximum installed capacity of up to 4800 MW, but the first phase to be constructed and operated will be approximately half that installed capacity. The exact output will depend on the specification of the equipment installed and the ambient operating conditions. The footprint of the proposed new power station is still to be determined through final engineering and design, but has been indicated by Eskom that the new facility will be similar in size (ground footprint) to the existing Matimba Power Station. The power plant and associated plant (terrace area) would require an area of approximately 700 ha, and an additional approximate 500 - 1000 ha would be required for ancillary services, including ashing facilities (alternate ash disposal options are, however, currently being investigated). It is envisaged that the proposed power station will utilise a range of technologies pertaining to cooling, combustion and pollution abatement. -

Mean Streets: Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa

Mean Streets Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa Published by the Southern African Migration Programme (SAMP), the African Centre for Cities (ACC) and the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) Southern African Migration Programme, International Migration Research Centre Balsillie School of International Affairs, 67 Erb Street West, Waterloo, Ontario N2L 6C2, Canada African Centre for Cities, University of Cape Town, Environmental & Geographical Science Building, Upper Campus, Rondebosch, 7701, South Africa International Development Research Centre, 160 Kent St, Ottawa, Canada K1P 0B2 and Eaton Place, 3rd floor, United Nations Crescent, Gigiri, Nairobi, Kenya ISBN 978-1-920596-11-8 © SAMP 2015 First published 2015 Production, including editing, design and layout, by Bronwen Dachs Muller Cover by Michiel Botha Cover photograph by Alon Skuy/The Times. The photograph shows Soweto residents looting a migrant-owned shop in a January 2015 spate of attacks in South Africa Index by Ethné Clarke Printed by MegaDigital, Cape Town All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission from the publishers. Mean Streets Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa Edited by Jonathan Crush Abel Chikanda Caroline Skinner Acknowledgements The editors would like to acknowledge the financial and programming support of the Inter- national Development Research Centre (IDRC), which funded the research of the Growing Informal Cities Project and the Workshop on Urban Informality and Migrant Entrepre- neurship in Southern African Cities hosted by SAMP and the African Centre for Cities in Cape Town in February 2014. Many of the chapters in this volume were first presented at this workshop.