Mean Streets: Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete Dissertation

VU Research Portal Itineraries Rousseau, N. 2019 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Rousseau, N. (2019). Itineraries: A return to the archives of the South African truth commission and the limits of counter-revolutionary warfare. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 09. Oct. 2021 VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT Itineraries A return to the archives of the South African truth commission and the limits of counter-revolutionary warfare ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. V. Subramaniam, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van de promotiecommissie van de Faculteit der Geesteswetenschappen op woensdag 20 maart 2019 om 15.45 uur in de aula van de universiteit, De Boelelaan 1105 door Nicky Rousseau geboren te Dundee, Zuid-Afrika promotoren: prof.dr. -

Cape Town's Film Permit Guide

Location Filming In Cape Town a film permit guide THIS CITY WORKS FOR YOU MESSAGE FROM THE MAYOR We are exceptionally proud of this, the 1st edition of The Film Permit Guide. This book provides information to filmmakers on film permitting and filming, and also acts as an information source for communities impacted by film activities in Cape Town and the Western Cape and will supply our local and international visitors and filmmakers with vital guidelines on the film industry. Cape Town’s film industry is a perfect reflection of the South African success story. We have matured into a world class, globally competitive film environment. With its rich diversity of landscapes and architecture, sublime weather conditions, world-class crews and production houses, not to mention a very hospitable exchange rate, we give you the best of, well, all worlds. ALDERMAN NOMAINDIA MFEKETO Executive Mayor City of Cape Town MESSAGE FROM ALDERMAN SITONGA The City of Cape Town recognises the valuable contribution of filming to the economic and cultural environment of Cape Town. I am therefore, upbeat about the introduction of this Film Permit Guide and the manner in which it is presented. This guide will be a vitally important communication tool to continue the positive relationship between the film industry, the community and the City of Cape Town. Through this guide, I am looking forward to seeing the strengthening of our thriving relationship with all roleplayers in the industry. ALDERMAN CLIFFORD SITONGA Mayoral Committee Member for Economic, Social Development and Tourism City of Cape Town CONTENTS C. Page 1. -

Somalinomics

SOMALINOMICS A CASE STUDY ON THE ECONOMICS OF SOMALI INFORMAL TRADE IN THE WESTERN CAPE VANYA GASTROW WITH RONI AMIT 2013 | ACMS RESEARCH REPORT ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research report was produced by the African Centre for Migration & Society at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, with support from Atlantic Philanthropies. The report was researched and written by Vanya Gastrow, with supervision and contributions from Roni Amit. Mohamed Aden Osman, Sakhiwo ‘Toto’ Gxabela, and Wanda Bici provided research assistance in the field sites. ACMS wishes to acknowledge the research support of various individuals, organisations and government departments. Abdi Ahmed Aden and Mohamed Abshir Fatule of the Somali Retailers Association shared valuable information on the experiences of Somali traders in Cape Town. Abdikadir Khalif and Mohamed Aden Osman of the Somali Association of South Africa, and Abdirizak Mursal Farah of the Somali Refugee Aid Agency assisted in providing advice and arranging venues for interviews in Bellville and Mitchells Plain. Community activist Mohamed Ahmed Afrah Omar also provided advice and support towards the research. The South African Police Service (SAPS) introduced ACMS to relevant station commanders who in turn facilitated interviews with sector managers as well as detectives at their stations. Fundiswa Hoko at the SAPS Western Cape provincial office provided quick and efficient coordination. The Department of Justice and Constitutional Development facilitated interviews with prosecutors, and the National Prosecuting Authority provided ACMS with valuable data on prosecutions relating to ‘xenophobia cases’. ACMS also acknowledges the many Somali traders and South African township residents who spoke openly with ACMS and shared their views and experiences. -

Kloof-Driefontein Complex (KDC) Technical Short Form Report 31 December 2011

Kloof-Driefontein Complex (KDC) Technical Short Form Report 31 December 2011 2 Salient features ¨ Mineral Resources at 63.8 Moz (excluding Tailing Storage Facility ounces of 3.7 Moz). ¨ Mineral Reserves at 13.7 Moz (excluding Tailing Storage Facility ounces of 2.9 Moz). ¨ Safe steady state production strategy driving quality volume. ¨ Accelerate extraction of higher grade Mineral Reserves to bring value forward. ¨ Optimise surface resources extraction strategy. ¨ Long-life franchise asset anchoring gold production to 2028 (17 years). The KDC has a world class ore body with long-life Mineral Resources and Mineral Reserves (17 years) which has produced in excess of 181 Moz from the renowned Witwatersrand Basin, the most prolific gold depository in the world. Geographic location KDC West Mining Right KDC East Mining Right Carletonville Pretoria Johannesburg Welkom Kimberley Bloemfontein Durban KDC East = Kloof G.M. Port Elizabeth KDC West = Driefontein G.M. Cape Town Gold Fields: KDC Gold Mine – Technical Short Form Report 2011 3 Geographic location IFC 1. Overview 1. Overview Page 1 Gold Fields Limited owns a 100% interest in GFI Mining South Africa (Pty) Limited (GFIMSA), which holds a 100% interest in KDC (Kloof- 2. Key aspects Page 2 Driefontein Complex). The mine is situated between 60 and 80 kilometres west of 3. Operating statistics Page 3 Johannesburg near the towns of Westonaria and Carletonville in the Gauteng Province of Page 4 South Africa. KDC is a large, well-established 4. Geological setting and mineralisation shallow to ultra-deep level gold mine with workings that are accessed through, 12 shaft 5. Mining Page 7 systems (five business units – BU’s) that mine various gold-bearing reefs from open ground 6. -

Opposition Party Mobilization in South Africa's Dominant

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Eroding Dominance from Below: Opposition Party Mobilization in South Africa’s Dominant Party System A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Safia Abukar Farole 2019 © Copyright by Safia Abukar Farole 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Eroding Dominance from Below: Opposition Party Mobilization in South Africa’s Dominant Party System by Safia Abukar Farole Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Kathleen Bawn, Chair In countries ruled by a single party for a long period of time, how does political opposition to the ruling party grow? In this dissertation, I study the growth in support for the Democratic Alliance (DA) party, which is the largest opposition party in South Africa. South Africa is a case of democratic dominant party rule, a party system in which fair but uncompetitive elections are held. I argue that opposition party growth in dominant party systems is explained by the strategies that opposition parties adopt in local government and the factors that shape political competition in local politics. I argue that opposition parties can use time spent in local government to expand beyond their base by delivering services effectively and outperforming the ruling party. I also argue that performance in subnational political office helps opposition parties build a reputation for good governance, which is appealing to ruling party ii. supporters who are looking for an alternative. Finally, I argue that opposition parties use candidate nominations for local elections as a means to appeal to constituents that are vital to the ruling party’s coalition. -

Graaff-Reinet: Urban Design Plan August 2012 Contact Person

Graaff-Reinet: Urban Design Plan August 2012 Contact Person: Hedwig Crooijmans-Allers The Matrix cc...Urban Designers and Architects 22 Lansdowne Place Richmond Hill Port Elizabeth Tel: 041 582 1073 email: [email protected] GRAAFF -REINET: URBAN DESIGN PLAN Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 6 1.1. General .............................................................................................................................................................. 6 1.2. Stakeholder and Public Participation Process ................................................................................................... 6 A: Traffic Study 2. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 8 2.1. Background ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 2.2. Methodology ..................................................................................................................................................... 8 2.3. Study Area ........................................................................................................................................................ -

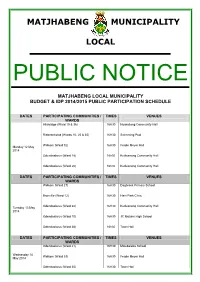

Matjhabeng Municipality Local

MATJHABENG MUNICIPALITY LOCAL PUBLIC NOTICE MATJHABENG LOCAL MUNICIPALITY BUDGET & IDP 2014/2015 PUBLIC PARTICIPATION SCHEDULE DATES PARTICIPATING COMMUNITIES / TIMES VENUES WARDS Allanridge (Ward 19 & 36) 16H30 Nyakallong Community Hall Riebeeckstad (Wards 10, 25 & 35) 16H30 Swimming Pool Welkom (Ward 32) 16H30 Ferdie Meyer Hall Monday 12 May 2014 Odendaalsrus (Ward 18) 16h30 Kutlwanong Community Hall Odendaalsrus (Ward 20) 16h30 Kutlwanong Community Hall DATES PARTICIPATING COMMUNITIES / TIMES VENUES WARDS Welkom (Ward 27) 16H30 Dagbreek Primary School Bronville (Ward 12) 16H30 Hani Park Clinic Odendaalsrus (Ward 22) 16H30 Kutlwanong Community Hall Tuesday 13 May 2014 Odendaalsrus (Ward 10) 16H30 JC Motumi High School Odendaalsrus (Ward 36) 16h30 Town Hall DATES PARTICIPATING COMMUNITIES / TIMES VENUES WARDS Odendaalsrus (Ward 21) 16H30 Malebaleba School Wednesday 14 Welkom (Ward 33) 16H30 Ferdie Meyer Hall May 2014 Odendaalsrus (Ward 35) 16H30 Town Hall Bronville (Ward 11) 16H30 Bronville Community Hall Welkom (Ward 24) 16H30 Reahola Housing Units DATES PARTICIPATING COMMUNITIES / TIMES VENUES WARDS Bronville (Ward 23) 16H30 Hani Park Church Thabong (Ward 12) 16H30 Tsakani School Thursday 15 May Thabong (Ward 30) 16H30 Thabong Primary School 2014 Thabong (Ward 31) 16H30 Thabong Community Centre Thabong (Ward 28) 16H30 Thembekile School DATES PARTICIPATING COMMUNITIES / TIMES VENUES WARDS Thabong (Ward 26) 16H30 Bofihla School Thabong (Ward 29) 16H30 Lebogang School Monday 19 May 2014 Thabong Far East (Ward 25) 16H30 Matshebo School -

Living History – the Story of Adderley Street's Flower

LIVING HISTORY – THE STORY OF ADDERLEY STREET’S FLOWER SELLERS Lizette Rabe Department of Journalism, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch 7602 Lewende geskiedenis – die verhaal van Adderleystraat se blommeverkopers Kaapstad is waarskynlik sinoniem met Tafelberg. Maar een van die letterlik kleurryke tonele aan die voet van dié berg is waarskynlik eweneens sinoniem met die stad: Adderleystraat se “beroemde” blommeverkopers. Tog word hulle al minder, hoewel hulle deel van Kaapstad se lewende geskiedenis is en letterlik tot die Moederstad se kleurryke lewe bygedra het en ’n toerismebaken is. Waar kom hulle vandaan, en belangrik, wat is hulle toekoms? Dié beskrywende artikel binne die paradigma van mikrogeskiedenis is sover bekend ’n eerste sosiaal-wetenskaplike verkenning van die geskiedenis van dié unieke groep Kapenaars, die oorsprong van die blommemark en sy kleurryke blommenalatenskap. Sleutelwoorde: Adderleystraat; blommemark; blommeverkopers; Kaapstad; kultuurgeskiedenis; snyblomme; toerisme; veldblomme. Cape Town is probably synonymous with Table Mountain. But one of the colourful scenes at the foot of the mountain may also be described as synonymous with the city: Adderley Street’s “famous” fl ower market. Yet, although the fl ower sellers are part of Cape Town’s living history, a beacon for tourists, and literally contributes to the Mother City’s vibrant and colourful life, they represent a dying breed. Where do they come from, and more importantly, what is their future? This descriptive article within the paradigm of microhistory is, thus far known, a fi rst social scientifi c exploration of the history of this unique group of Capetonians, the origins of the fl ower market, and its fl ower legacy. -

MSDF 2019 Annexure a IMPLEMENTATION

MERAFONG CITY MUNICIPAL SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK 2019 ANNEXURE A IMPLEMENTATION PLAN CAPITAL INVESTMENT FRAMEWORK The Capital Expenditure Framework (CEF) as a component of the Municipal Spatial Development Framework (MSDF) is a requirement in terms of Section 21(n) of the Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act, 2013. The intention of the Capital Investment Framework (CIF) is to close the gap between the spatial strategy and implementation on the ground. This is to be achieved using the spatial strategy and the detail provided in the Municipal Spatial Development Framework as the basis upon which other sector plans can be built, thus ensuring integration through a shared platform. A Capital Expenditure Framework has 4 key components namely spatial alignment, quantification of growth, technical assessment and financial alignment. This is the first attempt at an improved Capital Expenditure Framework and whilst the spatial component has been completed satisfactorily, the financial and infrastructure components are not at a satisfactory level. The municipality strives to adopt the new Integrated Urban Development Grant (IUDG) and as such the infrastructure and financial components will have to be added in coming years. This attempt is seen as a base to start from and expand upon. Many of the calculations and information available has not been included and some of it, such as the human settlement calculations are included in other parts of the MSDF. The municipality has a very difficult task of balancing its budget between the needs of social development, economic development and urban efficiency. The needs of the present must also be weighed against sustainability and viability in the future. -

CT, Franschoek, Eastern Cape

T H E A F R I C A H U B S O U T H B Y S M A L L W O R L D M A R K E T I N G A F R I C A T r u s t e d i n s i d e r k n o w l e d g e f r o m h a n d p i c k e d e x p e r t s S A M P L E I T I N E R A R Y # 1 I N P A R T N E R S H I P W I T H N E W F R O N T I E R S T O U R S Cape Town, Franschoek "South Africa can be overwhelming to sell due & Eastern Cape Safari to the sheer variety of locations and 9 nights accommodation options. This SA information sharing partnership between SWM and New Frontiers is invaluable in helping to inform & enthuse aficionados and non-specialists alike." - Albee Yeend, Albee's Africa W W W . S M A L L W O R L D M A R K E T I N G . C O . U K / T H E A F R I C A H U B I T I N E R A R Y W H O ? O V E R V I E W Families | Couples H I G H L I G H T S 4 nights | Cape Grace Cape Grace offers an excellent location to 2 nights | Boschendal explore the city from 3 nights | Kwandwe Great Fish River Lodge Treehouse experience included in Boschendal stay Guests will spend their first 4 nights Exceptional game viewing experience in the discovering Cape Town. -

Westonaria SAPS in Carletonville Cluster

10 July 2009, RANDFONTEIN HERALD Page 5 Westonaria SAPS in Carletonville cluster Westonaria — Following the incor- above crimes reported in the whole poration of Merafong into Gauteng, cluster, on a weekly basis. Carletonville SAPS has now be- This team will work from the Uni- come the accountable station for all cus Building under the command of other stations in its cluster, includ- Superintendent Reginald Shabangu. ing Westonaria. "The Roadblock Task team consists The Carletonville SAPS cluster of 20 members from each of the consists of Khutsong, Fochville, station's crime prevention units and Wedela and now Westonaria police will concentrate their efforts on major station. routes such as the N12 and the Carletonville SAPS spokesman, P111." Sergeant Busi Menoe, says there will She adds that the main purpose of also be an overall commander for the this task team will be to prevent whole cluster. crimes such as house robberies, car "At this stage there is an interim hijackings and business robberies. acting cluster commander, Director "They will also be on the look-out Fred Kekana, who is based at the for stolen property and vehicles." Station Commissioner, Director Patricia Rampota, salutes Captain Richard Vrey during the Randfontein Westonaria station." Menoe says these members are di- SAPS medal parade. Menoe adds that two task teams vided into two groups under the com- have also been established to fight mand of captains Robert Maphasha crime in the whole cluster, namely the and Lot Nkoane. SAPS members honoured at parade Trio Task team and the Roadblock "The two groups will work flexi- Task team. -

Merafong Municipal Spatial Development Framework

2016 - 2021 2016 - 2021 Merafong Municipal Spatial Development Framework Produced by Christiaan de Jager Spatial Planning & Environmental Management Section Merafong City Local Municipality MERAFONG |MSDF 0 Compiled by Christiaan de Jager Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ............................................................................................... 2 2. NATIONAL, PROVINCIAL AND DISTRICT SCALE POLICY GUIDELINES .................................................. 9 3. THE STUDY AREA .......................................................................................................................... 28 4. SPATIAL ANALYSIS ........................................................................................................................ 29 5. SPATIAL DIRECTIVES ..................................................................................................................... 55 6. THE SDF MAP ............................................................................................................................. 124 ANNEXURE A IMPLEMENTATION PLAN ANNEXURE B NODES AND CORRIDORS ANNEXURE C LOCAL SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT DIRECTIVES MERAFONG |MSDF 1 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND In terms of chapter 5 of the Municipal Systems Act, 2000 (Act 32 of 2000), the municipality’s Integrated Development Plan “…must reflect a Spatial Development Framework which must include the provision for basic guidelines for a Land Use Management System for the municipality”. The Merafong Municipal Spatial Development Framework