Download/Pdf/39666742.Pdf De Vries, Fred (2006)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Article Differing Interpretations of Reconciliation in South Africa

Article Differing interpretations of reconciliation in South Africa: a discussion of the home for all campaign1 Sally Matthews [email protected] Abstract The theme of reconciliation remains an important one in South African politics. The issue of reconciliation was recently highlighted by South African Human Rights Commission chairperson, Jody Kollapen. According to Kollapen, in South Africa we have a problematic narrow interpretation of reconciliation, one that presents reconciliation and transformation as being in opposition to one another. This paper explores some of the debates about reconciliation as a process and then relates these to the Home for All Campaign. This Campaign was aimed at encouraging white South Africans to acknowledge the injustices of the past and to commit themselves to healing divisions and reducing inequalities in contemporary South Africa. It conceived of reconciliation as a process in which the onus is on white South Africans to take the initiative in reconciling with black South Africans. The Campaign received much publicity and provoked debate but never managed to gain the support of a significant number of white South Africans. In this paper, I explore the reasons for the Campaign’s failure to meet all of its objectives, relating this to contemporary South African discourse on reconciliation. I argue that the Campaign’s interpretation of reconciliation was valuable and necessary and that it remains imperative in South Africa that white South Africans critically reflect upon past and present privileges and take the initiative in processes of inter-racial reconciliation. More than fifteen years after the end of apartheid the topic of post-apartheid inter-racial reconciliation in South Africa remains pertinent. -

MD3463 R05.18 D01 Bez Valley-BAR

REPORT Draft Consultation Basic Assessment Report for the Upgrade of the Bezuidenhout Valley Clinic and Associated Infrastructure in Johannesburg, Gauteng Province Client : Johannesburg Development Agency Reference: T&PMD3463R001F0.1 Revision: 0.1/Final Date: 01 October 2018 Project Related ROYAL HASKONINGDHV (PTY) LTD 21 Woodlands Drive Building 5 Country Club Estate Woodmead Johannesburg 2191 Transport & Planning Reg No. 1966/001916/07 +27 11 798 6000 T +27 11 798 6005 F [email protected] E royalhaskoningdhv.com W Document title: Draft Consultation Basic Assessment Report for the Upgrade of the Bezuidenhout Valley Clinic and Associated Infrastructure in Johannesburg, Gauteng Province Reference: T&PMD3463R001F0.1 Revision: 0.1/Final Date: 01 October 2018 Project name: Upgrade of the Bezuidenhout Valley Clinic and Associated Infrastructure Project number: MD3463 Author(s): Sibongile Gumbi Drafted by: Sibongile Gumbi Checked by: Malcolm Roods Date / initials: MR Approved by: Malcolm Roods Date / initials: MR Classification Project related Disclaimer No part of these specifications/printed matter may be reproduced and/o r published by print, photocopy, microfilm or by any other means, without the prior written permission of Royal HaskoningDHV (Pty) Ltd; nor may they be used, without such permission, for any purposes other than that for which they were produced. Royal HaskoningDHV (Pty) Ltd accepts no responsibility or liability for these specifications/printed matter to any party other than the persons by whom it was commissioned and as concluded under that Appointment. The integrated QHSE management system of Royal HaskoningDHV (Pty) Ltd has been certified in accordance with ISO 9001:2015, ISO 14001:2015 and OHSAS 18001:2007. -

Short Stories Study Guide 12 © Department of Basic Education 2015

English First Additional Language Paper 2: Literature Short Stories Grade Study Guide 12 © Department of Basic Education 2015 This content may not be sold or used for commercial Acknowledgements purposes. The Department of Basic Education gratefully acknowledges the permission granted to reproduce Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) extracts from the original short stories in this CAPS Grade 12 English First Additional Language Mind the Gap study guide for Short Stories ISBN 978-1-4315-1944-6 Extracts from Manhood by John Wain are reproduced by permission of Will Wain for the This publication has a Creative Commons Attribution Estate of John Wain, the copyright holder. NonCommercial Sharealike license. You can use, modify, upload, download, and share content, but you Extracts from The Luncheon by W. Somerset must acknowledge the Department of Basic Education, Maugham are reproduced by permission of AP the authors and contributors. If you make any changes to the content you must send the changes to the Collected Department of Basic Education. This content may not Short Stories by W. Somerset Maugham, published be sold or used for commercial purposes. For more by Vintage Classics 2009. information about the terms of the license please see: Extracts from The Soft Voice of the Serpent by http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/. Nadine Gordimer are reproduced by permission of Copyright © Department of Basic Education 2015 222 Struben Street, Pretoria, South Africa originally published in The Soft Voice of the Serpent Contact person: Dr Patricia Watson and Other Stories, Simon and Schuster, 1952. Email: [email protected] Tel: (012) 357 4502 Extracts from Relatives by Chris van Wyk are http://www.education.gov.za reproduced by permission of the author. -

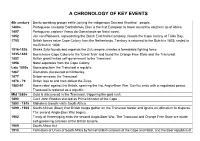

Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd Is Assassinated in the House of Assembly by a Parliamentary Messenger, Dimitri Tsafendas on 6 September

Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd is assassinated in the House of Assembly by a parliamentary messenger, Dimitri Tsafendas on 6 September. Balthazar J Vorster becomes Prime Minister on 13 September. 1967 The Terrorism Act is passed, in terms of which police are empowered to detain in solitary confinement for indefinite periods with no access to visitors. The public is not entitled to information relating to the identity and number of people detained. The Act is allegedly passed to deal with SWA/Namibian opposition and NP politicians assure Parliament it is not intended for local use. Besides being used to detain Toivo ya Toivo and other members of Ovambo People’s Organisation, the Act is used to detain South Africans. SAP counter-insurgency training begins (followed by similar SADF training in the following year). Compulsory military service for all white male youths is extended and all ex-servicemen become eligible for recall over a twenty-year period. Formation of the PAC armed wing, the Azanian Peoples Liberation Army (APLA). MK guerrillas conduct their first military actions with ZIPRA in north-western Rhodesia in campaigns known as Wankie and Sepolilo. In response, SAP units are deployed in Rhodesia. 1968 The Prohibition of Political Interference Act prohibits the formation and foreign financing of non-racial political parties. The Bureau of State Security (BOSS) is formed. BOSS operates independently of the police and is accountable to the Prime Minister. The PAC military wing attempts to reach South Africa through Botswana and Mozambique in what becomes known as the Villa Peri campaign. 1969 The ANC holds its first Consultative (Morogoro) Conference in Tanzania, and adopts the ‘Strategies and Tactics of the ANC’ programme, which includes its new approach to the ‘armed struggle’ and ‘political mobilisation’. -

Apartheid Revolutionary Poem-Songs. the Cases of Roger Lucey and Mzwakhe Mbuli

Corso di Laurea magistrale (ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004) in Lingue e Letterature Europee, Americane e Postcoloniali Apartheid Revolutionary Poem-Songs. The Cases of Roger Lucey and Mzwakhe Mbuli Relatore Ch. Prof. Marco Fazzini Correlatore Ch. Prof. Alessandro Scarsella Laureanda Irene Pozzobon Matricola 828267 Anno Accademico 2013 / 2014 ABSTRACT When a system of segregation tries to oppress individuals and peoples, struggle becomes an important part in order to have social and civil rights back. Revolutionary poem-songs are to be considered as part of that struggle. This dissertation aims at offering an overview on how South African poet-songwriters, in particular the white Roger Lucey and the black Mzwakhe Mbuli, composed poem-songs to fight against apartheid. A secondary purpose of this study is to show how, despite the different ethnicities of these poet-songwriters, similar themes are to be found in their literary works. In order to investigate this topic deeply, an interview with Roger Lucey was recorded and transcribed in September 2014. This work will first take into consideration poem-songs as part of a broader topic called ‘oral literature’. Secondly, it will focus on what revolutionary poem-songs are and it will report examples of poem-songs from the South African apartheid regime (1950s to 1990s). Its third part will explore both the personal and musical background of the two songwriters. Part four, then, will thematically analyse Roger Lucey and Mzwakhe Mbuli’s lyrics composed in that particular moment of history. Finally, an epilogue will show how the two songwriters’ perspectives have evolved in the post-apartheid era. -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

Mean Streets: Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa

Mean Streets Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa Published by the Southern African Migration Programme (SAMP), the African Centre for Cities (ACC) and the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) Southern African Migration Programme, International Migration Research Centre Balsillie School of International Affairs, 67 Erb Street West, Waterloo, Ontario N2L 6C2, Canada African Centre for Cities, University of Cape Town, Environmental & Geographical Science Building, Upper Campus, Rondebosch, 7701, South Africa International Development Research Centre, 160 Kent St, Ottawa, Canada K1P 0B2 and Eaton Place, 3rd floor, United Nations Crescent, Gigiri, Nairobi, Kenya ISBN 978-1-920596-11-8 © SAMP 2015 First published 2015 Production, including editing, design and layout, by Bronwen Dachs Muller Cover by Michiel Botha Cover photograph by Alon Skuy/The Times. The photograph shows Soweto residents looting a migrant-owned shop in a January 2015 spate of attacks in South Africa Index by Ethné Clarke Printed by MegaDigital, Cape Town All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission from the publishers. Mean Streets Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa Edited by Jonathan Crush Abel Chikanda Caroline Skinner Acknowledgements The editors would like to acknowledge the financial and programming support of the Inter- national Development Research Centre (IDRC), which funded the research of the Growing Informal Cities Project and the Workshop on Urban Informality and Migrant Entrepre- neurship in Southern African Cities hosted by SAMP and the African Centre for Cities in Cape Town in February 2014. Many of the chapters in this volume were first presented at this workshop. -

Child-Headed Families Need Support – Those Who Died Continued from Page 1

newsnewsA publication of the Catholic Archdiocese of Johannesburg C-YOM 8-98-9 RIP Fr Teboho Matseke 55 Fr Emil Telephone (011) 402 6400 • www.catholicjhb.org.za7 DECEMBER 2020 Fr Emil Blaser, with Sr Justina Priess OP and Fr Barney McAleer, was the founding editor of the ADNews in 1985 when newspapers were not allowed to report incidents of anti- hild-headed households a apartheid resistance. The first issue carried a report of the petrol bombing of the Child-headed families ADADconvent of the Companions of St Angela. On the right is Judy Stockill, editor of a problem in many South ADNews until 2012 who is still a contributor. For more about Fr Emil, see pages 8 and 9. CAfrican families escalated need support by the Covid-19 pandemic. Greater burden has also been Cases where the grandchildren parishioners who present cases of placed on grandparents who are are the primary caregivers are indigent families in their streets now being forced to support common. One instance was of and communities. their children, as well as grand- a grandmother who had seven “We engage the most mature children, because of recent job mouths to feed living in a one- child and, as with all cases, losses. room shack. They all depended we strive for lasting solutions, The Society of St Vincent de only on her pension grant to however, our priority is to ensure Paul is one of the largest and survive. that the family has access to basic long-standing charitable organ- “When we returned to follow- necessities. isations in the Archdiocese whose up, the eldest grandchild who “Children from these families core value is serving the poor. -

Inner City Eastern Gateway Urban Development Framework & Implementation Plan Report | 2016

INNER CITY EASTERN GATEWAY URBAN DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK & IMPLEMENTATION PLAN REPORT | 2016 Prepared for: Prepared by: CITY OF JOHANNESBURG & OSMOND LANGE ARCHITECTS JOHANNESBURG DEVELOPMENT & PLANNERS (Pty) Ltd AGENCY Unit 3, Ground Floor The Bus Factory 3 Melrose Boulevard No. 3 President Street Melrose Arch Newtown 2196 Johannesburg [t]: 011 994 4300 [t]: 011 688 7851 [f]: 011 684 1436 [f]: 011 688 7899 email: [email protected] In Collaboration with: URBAN- ECON , HATCH GOBA, U SPACE & TANYA ZACK DEVELOPMENT PLANNERS 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8.0 URBAN DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK 8.1 VISION PLAN 2.0. INTRODUCTION 8.2 LAND USE 8.2.1. PROPOSED LAND USES 3.0. STATUS QUO 8.2.2. ZONING 3.1 REGIONAL CONTEXT 8.3 PUBLIC ENVIRONMENT 3.1.1 LOCALITY 8.3.1. PUBLIC REALM 3.1.2 GAUTENG CITY REGION CONTEXT 8.3.2 MOVEMENT NETWORK 3.1.3 METROPOLITAN CONTEXT 8.3.3. PARKS & GREEN SPACES 3.1.4 THE ROLE OF JOHANNESBURG INNER CITY 8.4 BUILT FORM 3.1.5 AEROTROPOLIS CONTEXT 8.4.1. HEIGHT AND GRAIN GUIDELINES 8.4.2. STREET EDGE GUIDELINES 8.5 HOUSING 3.2 STUDY AREA 8.5.1. ASSUMPTIONS: NUMBER OF HOUSEHOLDS THAT 3.2.1 NATURAL ENVIRONMENT REQUIRE HOUSING INTERVENTION I TOPOGRAPHY 8.5.2 ESTIMATES OF HOUSING NEED II OPEN SPACE SYSTEM 8.5.3 POSSIBLE INTERVENTIONS – HOUSING FORMS 3.2.2 BUILT ENVIRONMENT 8.5.4 APPLYING ICHIP IN EASTERN GATEWAY i LAND USE 8.5.5 LOGIC FOR HOUSING INTERVENTION II ZONING 8.5.6 ICHIP PRIORITY HOUSING PRECINCTS III BUILT FORM 8.5.7 HOUSING DELIVERY REQUIREMENTS iv HERITAGE 8.5.8 PROPOSED HOUSING INTERVENTIONS v TRANSPORT & TRAFFIC 8.5.9 PROPOSED HOUSING TYPOLOGIES 3.2.3 SOCIO- ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT 8.6 SOCIAL FACILITIES i POPULATION 8.6.1. -

A Chronology of Key Events

A CHRONOLOGY OF KEY EVENTS 4th century Bantu speaking groups settle, joining the indigenous San and Khoikhoi people. 1480s Portuguese navigator Bartholomeu Dias is the first European to travel round the southern tip of Africa. 1497 Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama lands on Natal coast. 1652 Jan van Riebeeck, representing the Dutch East India Company, founds the Cape Colony at Table Bay. 1795 British forces seize Cape Colony from the Netherlands. Territory is returned to the Dutch in 1803; ceded to the British in 1806. 1816-1826 Shaka Zulu founds and expands the Zulu empire, creates a formidable fighting force. 1835-1840 Boers leave Cape Colony in the 'Great Trek' and found the Orange Free State and the Transvaal. 1852 British grant limited self-government to the Transvaal. 1856 Natal separates from the Cape Colony. Late 1850s Boers proclaim the Transvaal a republic. 1867 Diamonds discovered at Kimberley. 1877 Britain annexes the Transvaal. 1878 - 79 British lose to and then defeat the Zulus 1880-81 Boers rebel against the British, sparking the first Anglo-Boer War. Conflict ends with a negotiated peace. Transvaal is restored as a republic. Mid 1880s Gold is discovered in the Transvaal, triggering the gold rush. 1890 Cecil John Rhodes elected as Prime Minister of the Cape 1893 - 1915 Mahatma Gandhi visits South Africa 1899 - 1902 South African (Boer) War British troops gather on the Transvaal border and ignore an ultimatum to disperse. The second Anglo-Boer War begins. 1902 Treaty of Vereeniging ends the second Anglo-Boer War. The Transvaal and Orange Free State are made self-governing colonies of the British Empire. -

Black Christ and Cross-Roads Jesus for White South African Christians

HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-8050, (Print) 0259-9422 Page 1 of 10 Original Research Black Christ and Cross-Roads Jesus for white South African Christians Author: A significant factor undermining real racial reconciliation in post-1994 South Africa is 1 Wilhelm J. Verwoerd widespread resistance to shared historical responsibility amongst South Africans racialised as Affiliation: white. In response to the need for localised ‘white work’ (raising self-critical, intragroup 1Studies in Historical Trauma historical awareness for the sake of deepened racial reconciliation), this article aims to Stellenbosch University, contribute to the uprooting of white denialism, specifically amongst Afrikaans-speaking Stellenbosch, South Africa Christians from (Dutch) Reformed backgrounds. The point of entry is two underexplored, Corresponding author: challenging, contextualised crucifixion paintings, namely, Black Christ and Cross-Roads Jesus. Wilhelm Johannes Verwoerd, Drawing on critical whiteness studies, extensive local and international experience as a [email protected] ‘participatory’ facilitator of conflict transformation and his particular embodiment, the author explores the creative unsettling potential of these two prophetic ‘icons’. Through this Dates: incarnational, phenomenological, diagnostic engagement with Black Christ, attention is drawn Received: 05 Oct. 2019 Accepted: 09 Mar. 2020 to the dynamics of family betrayal, ‘moral injury’ and idolisation underlying ‘white fragility’. Published: 30 July -

Black Consciousness and the Politics of Writing the Nation in South Africa

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository Black Consciousness and the Politics of Writing the Nation in South Africa by Thomas William Penfold A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of African Studies and Anthropology School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham May 2013 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract Since the transition from apartheid, there has been much discussion of the possibilities for the emergence of a truly ‘national’ literature in South Africa. This thesis joins the debate by arguing that Black Consciousness, a movement that began in the late 1960s, provided the intellectual framework both for understanding how a national culture would develop and for recognising it when it emerged. Black Consciousness posited a South Africa where formerly competing cultures sat comfortably together. This thesis explores whether such cultural equality has been achieved. Does contemporary literature harmoniously deploy different cultural idioms simultaneously? By analysing Black writing, mainly poetry, from the 1970s through to the present, the study traces the stages of development preceding the emergence of a possible ‘national’ literature and argues that the dominant art versus politics binary needs to be reconsidered.